Books

The Fragility of the Liberal World Order

For Kagan, the architects of the post-war order sought to wed America’s new-found superpower to the construction of a world order that reflected the domestic values of America itself: a liberal international order.

A review of The Jungle Grows Back: America and our Imperiled World by Robert Kagan. Knopf (September 2018) 192 pages.

In its natural state, international relations is little more than a ‘jungle.’ There is no umpire to ensure fair play, no global police force to punish wrongdoers, and ‘good boys’ are rarely rewarded. Prevaricate or show weakness and you risk being picked off and consumed by bigger beasts.

Prior to the end of the Second World War, European geopolitics was characterized by this remorseless logic. As states vied for hegemony, tens of millions were killed in war and conflict, and human tragedy and suffering were on scales almost beyond the imaginable. Today, however, we have complex forms of global economic interdependence, sets of global institutions that fuse us together and a transformed jungle that incentivize ‘good boys,’ as well as rules, norms and ultimately military power to make sure they remain good. How did our international jungle, an almost constant in human history, come to be so tamed?

In his latest book, The Jungle Grows Back: America and our Imperiled World, Robert Kagan details the coming to power of America. After the Second World War, Great Britain, the world’s previous hegemon, was bankrupt and the baton for world leadership passed inexorably from one great liberal democracy to another. This was a natural step, given the concentration of power into America’s hands. Its industrial capacity remained untouched, it possessed huge reserves of capital, it had a military power unmatched in human history and enjoyed regional hegemony across the Americas. Quite unique in history, however, and unlike previous great powers that have emerged victorious after major conflicts, America did not use this new-found power to construct a form of global imperial order that sought the decimation of the losers, territorial occupation or other forms of ‘bounty.’ For Kagan, the architects of the post-war order sought to wed America’s new-found superpower to the construction of a world order that reflected the domestic values of America itself: a liberal international order.

These values were universalist and sought to remake the world in America’s image, including a commitment to liberal democracy and human rights. More important was the self-restraint of American power within this new order. That is, the jungle’s biggest beast not only sought to reduce conflict by protecting the jungle’s lesser beasts, but also made itself subject to those same rules. Moreover, it did not try to kill off its former jungle rivals, but sought to restore them to health. This rehabilitation of Japan and Germany (East Asia and Europe’s natural hegemons) was the most “significant post-war revolution in international affairs,” says Kagan, as U.S. power helped transform these countries from the “ambitious, autocratic, military powerhouses they had been to the pacific, democratic economic powerhouses they eventually became.” Indeed, an extraordinary form of benign hegemony.

At the heart of this U.S.-led liberal post-war architecture was a quid pro quo. In return for recognizing that the U.S. was now the undisputed king of the jungle, both former enemies and its now subordinate allies would play by its rules. And while economic competition would take place (with Japan and Germany challenging U.S. economic hegemony as early as the 1970s) none would challenge the U.S. militarily or embark on military adventures of their own without permission (as the British learnt to their peril during the Suez crisis of 1956). In return, states within the U.S.-led liberal order would freely have access to U.S. markets and capital, as well as global rules and institutions to regularize political-economic interactions and a rules-based system that gave voice to weaker states and a structure to international relations.

This deal also contained a security component. If you were in the ‘liberal club’ you would also enjoy U.S. security protection. For Japan, this was codified within the U.S.-Japan Security Pact and for the Europeans the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The U.S. security guarantee not only checked and contained the threat of Soviet tyranny, but also pacified geopolitics in these key regions. Japan would grow economically, but no longer militarily threaten its neighbors, which in turn helped with regional economic integration. In Europe, U.S. military power became the security pre-condition for the complex forms of political and economic interdependence built up in the post-war period, with the U.S. the key architect of European integration. Lord Hastings, NATO’s first Secretary General, famously declared that the alliance was designed to “keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Alongside these benefits, the security provided by the U.S. also allowed the Europeans to build up large welfare states, not least because they did not have to foot the bill for their own security (well covered by Kagan’s 2003 book, Of Paradise and Power).

This order proved remarkably durable. After the end of the Cold War, NATO and the EU expanded into the former Soviet sphere of influence, and rising East Asian powers joined global institutions such as the World Trade Organization. All in all, the liberal order became the institutional instantiation of the U.S.’s modest global ambitions: world trade, a peaceful Europe and East Asia that looked to the U.S. for its security and an acceptance that, broadly speaking, the U.S. would occasionally act unilaterally to defend its national interests.

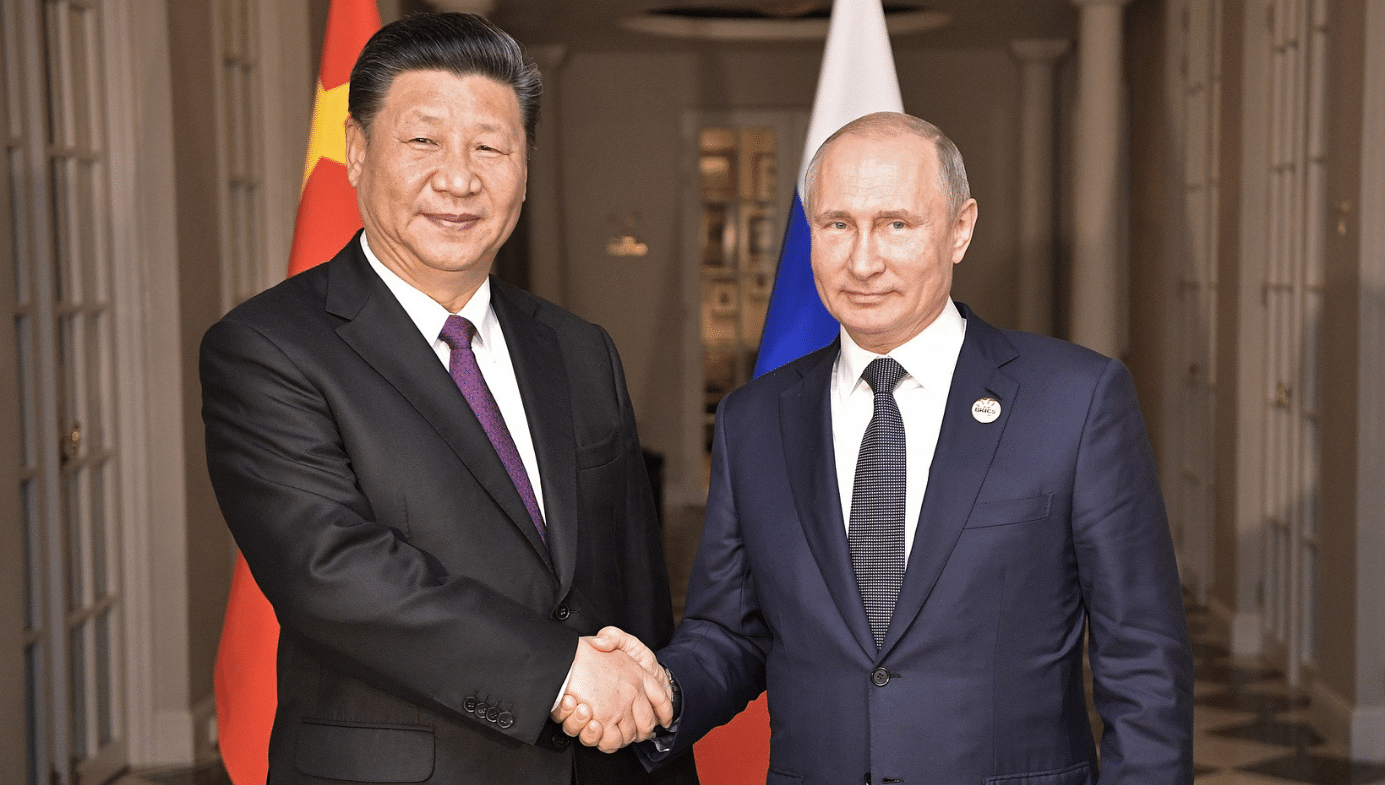

Despite these successes, however, a new illiberalism is afoot, according to Kagan. China’s one-party state is now seeking to re-assert its military power in East Asia. Meanwhile, Russia is seeking to reverse the humiliations of the post-Cold War settlement and restore its great power status. Both powers complain about the U.S.’s unipolarity and seek to dismantle the liberal world order which, for them, is a smokescreen for U.S. imperialism. But it’s not these developments that threaten that order, Kagan believes, so much as what’s happening in American domestic politics. Kagan, a neoconservative, argues that Obama’s weakness was the real problem, particularly his failure to reinforce America’s red lines in Syria—something that led to the U.S.’s Middle Eastern and Gulf allies to question American power. What good is a king of the jungle when he can no longer keep the bullies in line? While Obama was bad, Kagan argues, Trump poses an even greater threat. His economic nationalism threatens to unravel the world economic order and his populism has released dangerous forces in American politics. Tracing a genealogy from Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany to the alt-right of today, Kagan cautions that ‘Trumpism’ is allowing the jungle to take hold in America itself.

Is it too late to save the U.S.-led liberal order? Kagan remains sanguine. Despite its critics across the political spectrum, the world order’s architecture and institutions remains strong, not least because “they rest on geographical realities and a distribution of power that still favor the liberal order and still pose obstacles to those who would disrupt it.” Moreover, “liberal values, though under assault, remain a force that binds the democratic nations of the world together.”

How valuable is Kagan’s analysis and what should we make of the current state of American foreign policy? First, there is little here that has not been done elsewhere and often at much greater depth. Princeton’s John Ikenberry has long championed liberal international relations theory and, while not a neoconservative, his 2011 book Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American System and his masterful After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars(2001) provide a far more detailed and nuanced portrait of the historical contours of the liberal order. His work focuses on how great powers use moments of deep transformation in international relations to refashion world order in ways that reflect their national interests. To put it bluntly, why buy Kagan’s historical burger when you can have steak? (Full disclosure: I recently edited a special journal issue with Ikenberry and Inderjeet Parmar that you can find here.)

Second, Kagan is a little too hostile to Trump and his worldview. This worldview says that American foreign policy and economic elites have constructed a global system that benefits them to the detriment of the American worker (globalism). The outsourcing of jobs to China, mass immigration, stagnant wages, and the loss of America’s sense of self are part of the cost of globalization, according to Trump and his allies. This has taken place as bankers and Wall Street have made trillions for U.S. economic elites, while getting the U.S. tax payer to bail them out when their bets don’t pay off. Kagan isn’t very sympathetic to this populist nationalism, but given the blood and treasure that’s been spent on securing and maintaining the U.S.’s dominance, it’s reasonable to ask what exactly it is that ordinary Americans are getting from the liberal order?

U.S. foreign policy elites, of which Kagan is a part, need to work out how to reconcile America’s role as the guarantor of the liberal world order with the domestic costs this often generates. It may benefit the bi-coastal elite, but what of the ordinary workers in the flyover states? Globalization has contributed to the demise of the rust belt, the stagnation of wages and the disappearance of traditional blue-collar jobs. In the long economic boom following the Second World War, this dilemma was easier to manage; now, the benefits of American elites’ preferred global model has become a much harder sell to those who feel the economic costs to themselves and their families.

This short book is a valuable read and makes a valiant effort to argue for America’s continued deep engagement in the world. I share this sentiment, although this position will have many critics. Aside from the historical narrative that I have sketched above, the book has an important underlying message, one that neoconservatives have made consistently. The world order is not natural; it needed to be built and it needs to be carefully maintained. That it is a liberal world order is far from inevitable. Think, for example, what type of regional or even global order would have been constructed had Hitler won the Second World War? It matters who wins big wars.

More importantly for Kagan, the current world order needs a big beast to keep the bullies in check. The U.S. has often been highly hypocritical, and its sins of commission and omission are numerous, but if we accept that international orders will reflect the domestic values of the great powers that sustain them, what kind of alternative would we like to see? Kagan’s key message is that if you want peace, prepare for war. Human existence “is a constant battle among competing impulses—between self-love and the love of others, between the noble and the base, between the desire for freedom and the desire for order and security—and because those struggles never end, the fate of liberalism and democracy in the world is never settled. It is an illusion to believe that the present democratic age is eternal rather than transient, or that it can survive without constant tending and constant defense.”