History

Inducing People’s Employers to Fire Them Should Be a Civil Wrong

While social media inflames tensions, the law aims to remove emotion and passion from disputes.

If you aren’t from Australia or New Zealand you may be tempted to think of Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Day as simply a variation of Veteran’s Day or Remembrance Day—but for many Aussies (and Kiwis), it’s a little bit like Veteran’s Day combined with the Fourth of July or St. Patrick’s Day. It is a deeply patriotic holiday that many regard as a semi-sacred, particularly because we celebrate it on April 25 to mark the anniversary of the day in 1915 when Anzacs arrived on the shores of Gallipoli, Turkey to fight in a battle that would result in over ten thousand soldiers losing their lives. Like it or not, Anzac Day has become patriotic mythology.

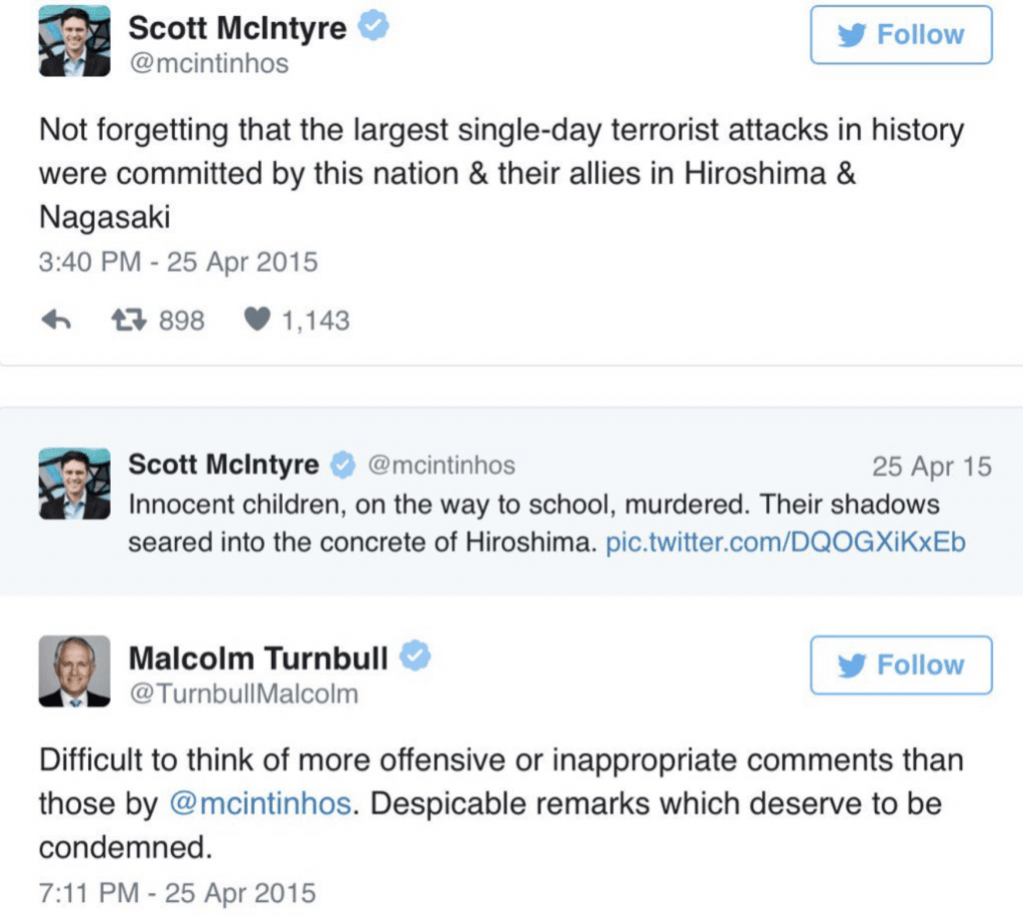

To mark Anzac Day in 2015, Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) reporter Scott McIntyre took to Twitter and wrote: “Remembering the summary execution, widespread rape and theft committed by these ‘brave’ Anzacs in Egypt, Palestine and Japan.” To make matters worse, he also asked “if the poorly-read, largely white, nationalist drinkers and gamblers pause today to consider the horror that all mankind suffered.” Then to round things off he added that Australia and its allies perpetrated the largest single-day “terrorist attacks in history” by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima & Nagasaki.

Happy Anzac Day, Australia.

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who was Communications Minister at the time, tweeted back to McIntyre that his tweets were “despicable remarks which deserve to be condemned.”

The following day the media reported that McIntyre had been sacked by SBS News although he later settled an action for unfair dismissal against the network.

Then in 2016 in what was dubbed a “witch hunt by conservative extremists,” La Trobe University temporarily stood down academic and LGBT anti-bullying advocate Roz Ward after she privately posted to Facebook a picture of a rainbow flag with the text: “Now we just need to get rid of the racist Australian flag on top of state parliament and get a red one up there and my work is done.” The reference to the “red one” was understood to refer to the socialist flag, as Ward is an active member of the Socialist Alternative. She was also the prominent co-founder of the “Safe Schools” program, designed to educate children about LGBT issues.

The backlash was swift but so was the defence of Ward by the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), who released a statement saying, “This NTEU branch stands firmly against such modern-day witch-hunts and calls on La Trobe University management to publicly state their support for Roz’s ongoing employment with Safe Schools Coalition.”

Yassmin Abdel-Magied also faced calls for her sacking from the national broadcaster after she posted on Facebook on Anzac Day 2017: “LEST. WE. FORGET. (Manus, Nauru, Syria, Palestine …).” (Manus and Nauru are Australia’s offshore asylum seeker processing centers). Abdel-Magied was not fired but instead the ABC program she hosted was axed.

But in Australia witch hunts are bipartisan. Conservative indignation for leftist ideas generates much the same treatment. In 2017, Dr. Pansy Lai appeared in a television advertisement for the ‘Coalition for Marriage’ calling for a vote against same-sex marriage. “When same-sex marriage passes as law overseas,” she said, “this type of program [the Safe Schools program] becomes widespread and compulsory.” Dr. Lai was threatened, and a petition was set up to demand that she be deregistered by the Australian Medical Association.

Earlier this year Australian rugby superstar Israel Folau wrote on his Instagram account that gay people would go to hell “unless they repent of their sins and turn to God.” He later published an anti-gay sermon on Twitter. This resulted in calls for him to leave Rugby Union, and speculation that Rugby Australia will not renew his contract.

'Sack Israel Folau': Liz Ellis urges Rugby Australia to act over 'homophobic' comment https://t.co/JuuUsnjwyb Folau was asked the Question and he replied - Ellis should go not Folau

— Stephen Russell (@SJWR) April 8, 2018

Sometimes it’s clear to see why someone’s controversial comments have an impact on their employment. For example, the former Victoria police assistant commissioner resigned after it was revealed he had made racist and sexist comments online under a pseudonym, including about colleagues and the commissioner. Given that he was the head of the police’s ethical standards body, his own ethics and neutrality were clearly called into question. But often, the offensive conduct is private and has nothing to do with how people perform their job.

Should a doctor be able to practice medicine because she opposes same-sex marriage, or should a reporter be able to keep his job if he criticizes Australia’s military history on Anzac Day? It’s my guess that depending on their politics, many Australians would passionately say yes to one but no to the other. So no matter what our political position when we express controversial views, whether from the left or the right, we count on offense, backlash and calls to get that person sacked. When we enter the realm of controversy, both sides want retribution and one of the most damning things you can do to a person is take away their livelihood.

Pitchfork-wielding mobs have always existed, but never have they been able to form in a matter of minutes and get people fired within hours. The speed of outrage on the internet moves so quickly that we could tweet something at the breakfast table before heading out the door for work only to find that when we arrive we don’t have a job. Whether we like it or not we are all governed by this rapid-growth wrath and the possibility that expressing our honest opinions on social media could destroy our careers.

As a practicing lawyer, I’m interested in looking at how social media is changing our ideas of justice and tort law. We live in a time when the dialogue itself can be the severest punishment we can inflict.

When people attempt to resolve disputes on their own, lawyers call it self-help. Self-help is all that exists in societies which lack an overarching legal system to determine rights and duties. Examples of self-help include something as benign as cutting off the branches from your neighbor’s tree when they overhang on your fence. However, self-help may also include trespassing on private property, or even assaulting a person. It is for this reason that the eminent textbook author Percy H. Winfield observed, “self-help has always been reckoned as a perilous remedy owing to the stringent rules against its abuse.” In other words, when people take the law into their own hands, the courts only allow it if the conduct is reasonable and proportionate. At its worst, self-help leads to vendettas, public shaming, and mob-violence.

In societies lacking functioning legal systems, feuds founded on self-help can descend into vendettas. Jared Diamond in The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? details his experiences in Papua New Guinea, where a driver named Malo accidentally strikes and kills a young boy named Billy. Diamond notes that in Papua New Guinea, drivers are allowed to flee the scene and head to the nearest police station because bystanders might drag them from their cars and beat them to death.

Adding to the tension in the incident Diamond describes, Malo and Billy were from different tribes and ethnic groups. In the event, the matter was resolved when Malo’s employer spoke to Billy’s father and offered to transfer food to Billy’s family, and gave a formal apology at Billy’s funeral. The first option with this kind of traditional justice is an attempt to achieve peace by compensation and negotiation, but if this doesn’t work, the second option is to seek personal retribution by violence, which tends to escalate into further retributive acts and then war. What is interesting about Diamond’s story is that the laws he describes are not an attempt to replace self-help but in fact work within the parameters of it.

While “an eye for an eye” may look bloodthirsty to us now, it was in fact an effort by ancient civilizations to forestall blood vendettas. In other words, the retributive response to an injury should be proportionate to the original injury, and the matter ends once proportionate retribution has been taken. Unlike Malo, the victims of a social media mobbing can’t flee. They can close their personal social media accounts, but they can’t stop people from calling, writing, emailing or campaigning against them. And we don’t have the capacity for peaceful negotiation in our modern global society, particularly when the mob is large, scattered and apt to expand exponentially.

My argument that social media campaigns are a form of self-help is at odds with the argument recently advanced by Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning in The Rise of Victimhood Culture. Campbell and Manning argue that social media campaigns to get people sacked are the opposite of self-help. This is because, unlike in the tribal Papua New Guinean context, they say that we have a comprehensive overarching governmental and legal system whereby we raise concerns with third parties to resolve disputes. Consequently, they assert that these situations involve “legal overdependency,” where rather than resolving their own disputes, people rely too heavily on an external third party.

Campbell and Manning deal specifically with disputes in the university context, where students bring claims of offensive behavior to university authorities rather than resolving them between themselves (which would be a form of self-help). They use the example of Nicholas and Erika Christakis, both of whom had to stand down as faculty-in-residence at Silliman College, Yale University, after students became offended by an email about Halloween costumes and then organized protests and petitions against the couple.

Nonetheless, there’s still a self-help aspect to these disputes. Typically, the third-party authority is afraid of the mob and accedes to the demands rather than making a decision based on principles of justice and the facts at hand. Decisions are not made based on the private law rights between the parties (what their employment contract states, or what wrong has been done). In fact, as Campbell and Manning outline, often these cases involve a startling lack of legal procedural protections.

Insofar as these decisions are said to represent legal decision-making, they don’t reflect the way law should operate in a liberal democracy. Every defendant is presumed innocent until proven guilty, all parties are accorded procedural fairness and entitled to know what accusations are made against them, and all defendants are entitled to a relevant legal defense. There is an absence of law here, particularly when it comes to social media and the quick retribution a social media mob can exact.

In fact, civil recourse theorists argue one of the aims of tort law is to prevent self-help as much as possible, particularly when it takes violent forms if people feel they’ve been wronged. Instead, courts vindicate the victim’s rights in a public forum. While social media inflames tensions, the law aims to remove emotion and passion from disputes. This was recognized by John Locke in his Second Treatise on Government, written in 1690:

…thus all private judgment of every particular member being excluded, the community comes to be umpire, by settled standing rules, indifferent, and the same to all parties; and by men having authority from the community, for the execution of those rules, decides all the differences that may happen between any members of that society concerning any matter of right; and punishes those offenses which any member hath committed against the society, with such penalties as the law has established…

This is the way in which liberal civil society should be organized. We want our disputes to be resolved by impartial judges who do not take sides, who drain the emotion out of matters, because a society that uses self-help to resolve disagreements is a more dangerous and violent one.

Democracy is predicated upon the free exchange of ideas. You might say, “Ah, but that doesn’t include a right to be offensive, and to hurt others!” The difficulty is that “offense” is a subjective term, and what is offensive to one person may simply be a joke to another or have no impact at all. Occasionally during my teaching evaluations, a student will write comments indicating I’m a ginger-haired nerd. I’m not offended. I made peace with the fact that I have red hair, glasses, and a prodigious enthusiasm for academic topics.

In Campbell and Manning’s terms, my response is typical of a “dignity culture,” where the proper response to personal insults is to ignore them or rise above them. I may also have a touch of “honor culture,” where the proper response to a personal insult is to strike back physically, but I suppress that response as unworthy. I do not reflect “victimhood culture,” where a person’s status is predicated upon their ability to tick certain categories of disadvantage related to oppression and minority status (the more boxes ticked, the higher the status). I could fit into several disadvantaged boxes if I wanted to, but I have spent my life trying to overcome disadvantage, not being defined by it.

But I understand that it can be traumatic to be on the receiving end of online abuse aimed at having you sacked from your job. I’ve received it myself for expressing certain opinions in public, and I’ve recently seen others (both colleagues and friends) receive similar abuse. Entire topics are off-limits for public discussion for me because of the abuse I received in the past. After my experience, several people told me, “We think the same as you do, but we’d never say it publicly.” Goodness knows, many others may have similar doubts to me, but we’ll never know, and in the meantime social policy will be predicated upon a totally different set of assumptions.

Joseph Overton postulated that there was an ever-shifting window of ideas that are politically acceptable (the “Overton window”). I feel as if the Overton window of acceptable political ideas is shifting to polarized extremes, and views which I have long held (e.g., I prefer to judge people according to their conduct, not as members of the ethnic group to which they belong) may now be regarded as unacceptable on parts of both right and left.

In Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification, Timur Kuran explains why it’s less than ideal to have situations where there is widespread preference falsification—where people don’t say what they really think out of fear. First, widely disliked social structures may be preserved because no one is brave enough to say publicly that they, too, do not agree. Secondly, social structures which are predicated on false preferences are prone to sudden collapse once the majority realizes that no one else likes or believes in the particular thing which is being upheld. Finally, preference falsification distorts public opinion, public discourse, and human knowledge. If people cannot openly discuss their views, then certain views will not be explored or discussed, and the sum of human knowledge will be diminished.

Resentments may also fester in ways that are unhealthy, and which may erupt in unpredictable ways. And in the context of people being sacked for unpopular or offensive views or comments, employers will respond to those who make the most noise, regardless of whether the majority of consumers actually care about the issue. With all of this in mind, we need disincentives to stop a small group of aggressive people from policing other people’s opinions.

Moreover, it is important to recall basic labor law principles, and why it’s wrong to sack people for expressing political opinions that we do not like. Trade unions were the first to assert that workers should not be sacked because of their political beliefs or because of the people with whom they associated, and they continue to fulfill this role. My own union, the NTEU, rightly supported academic Roz Ward, mentioned at the outset of this piece as having caused offence by questioning the Australian flag. However, it is also standing up for Professor Peter Ridd, an academic who questioned the theory that the Great Barrier Reef is dying as a result of global warming. James Cook University sacked Ridd for alleged “serious misconduct,” but he is (again rightly, in my view) being supported by the NTEU, even though many union members would disagree with his position.

In this excellent post, UK labor lawyer Virginia Mantouvalou considers the broader issue of employees being sacked over social media posts, and notes there’s a legal inconsistency between protection of freedom of speech in the UK and rights against employers. She says:

The employer cannot police workers’ moral character, their political opinions or their preferences. The retention of someone’s job should not depend on the tabloid press and the effect of its (mis)reporting on employers’ reputation. At present, speech that is protected against state interference is not protected in the employment context against dismissal and other disciplinary action. This is disturbing.

Dismissal can be devastating for its effect on income, reputation, and social life, as the Strasbourg Court itself has recognized, and even on people’s health.

The last point is a really important one. Employment is the way people make a living, but it can also be important to one’s identity and social status. To lose one’s job, or even to be at risk of losing one’s job, is so devastating that it can lead to PTSD or even suicide.

In an Australian context, an employer who sacked an employee would be subject to the Fair Work Act 2009. It’s worth noting that McIntyre—the reporter who was sacked for his offensive tweets on Anzac Day—brought an action in unfair dismissal under this legislation, but not all employees are able to take advantage of such laws, or even make it past the loss of a single pay check.

There’s another issue here, too. Why do employers not stand up for an employee in the face of mob pressure? My own theory is that it comes down to “corporate branding” and the way in which an individual’s “personal brand” is thought to mesh with the employer’s “corporate brand.” In other words, companies want to be perceived by the public in a certain way, and if individuals behave in a way that doesn’t match the brand, they must be disposed of before the brand is affected. This is even if the individual’s offensive comment is made in a private context and is not associated with their employment.

This strikes me as a form of market failure. Universities in particular should not operate according to corporate branding. A better indicator of the strength and health of a university is the extent to which it allows rigorous dissent and discussion, not in how it micromanages opinions expressed by staff.

I’ve talked above about the legal relationship between employer and employee, but what about the social media mob? This is a little more difficult. However, there are several tort doctrines which may be helpful. The first is defamation, which prohibits communication to third parties of false statements that injure the reputation of a person. Importantly, the defamatory statements are presumed to be untrue, and it is for the defendant to prove that they are in fact true (or “substantially true” in Australia). Unsurprisingly, social media defamation cases are on the rise, not only in Australia but around the world. Recently, a south Australian judge held a man liable not only for his Facebook posts, but also for the comments on those posts which brought a commercial rival into disrepute. Damages were awarded for the loss of business which resulted. Consequently, if persons make or even just allow defamatory comments on social media which lead to a person getting sacked, they may be liable.

The other relevant tort doctrines are the economic torts prohibiting interference with contractual relations: inducing breach of contract, interference with contractual relationships, and conspiracy.

The history of these torts is odd, although it does show they’re long-lived and flexible. They arise from the action of per quod servitium amisit or “loss of services,” a common law action which arose in early medieval England. The feudal lord was held to own not only the services of his servants, but also the services of his wife. Injury to the wife therefore gave rise to damages for “loss of consortium.” The tort of inducing breach of contract was an offshoot of loss of services and arose in the wake of the Black Death after a third to one half of the population in Britain had died.

In response to the resultant labor shortage, the English Parliament passed the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349, followed by the Statute of Labourers in 1351. The Statute made it a crime to break an existing contract of service and attempted to fix wages at pre-plague rates. It was generally unsuccessful at achieving this aim and is thought to be one of the factors leading to the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381. The Statute allowed judges to discover a common law action preventing a servant from breaking a contract and moving to a new master.

The modern tort of inducing breach of contract arose from the case of Lumley v. Gye, where Lumley (the manager of Her Majesty’s Theatre) sued Gye (the manager of Covent Garden Theatre) for inducing an opera singer, Johanna Wagner, to breach her contract to perform for Lumley in order to perform at his venue instead. The tort of inducing breach of contract later became notorious as it was part of the private law armory used by employers against trade unions, along with the contractual doctrine prohibiting restraint of trade, and the tort of conspiracy. Thus, in Taff Vale Railway Company v. Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants the tort of inducing breach of contract was used to hold unions liable for losses which companies suffered due to striking workers. All these doctrines were ameliorated by statute in due course.

Importantly, the longevity and flexibility of these torts are suggestive. The tort of inducing breach of contract is rarely used and as the brief history outlined above shows, it has generally been used by employers, either to prevent employees from working for a rival employer, or to prevent unions from encouraging members to refuse to work for certain organizations. However, it could be repurposed to protect employees, and to disincentivize social media mobs.

Could someone like Scott McIntyre take action against people who called for him to be stood down from SBS? His employment contract was clearly cancelled as a result of social media outrage, and certain public people were on record as saying his views were unacceptable (including Malcolm Turnbull). Damage flowed from the cancellation of the contract, although it is not clear whether the contract was in fact breached by his employer (I’m not aware of what the terms were). However, causation might be difficult to show. There was a social media pile-on and thus it might be difficult to prove (a) which individuals made the call to sack the employee and (b) that the calls in fact caused the sacking. It might be a situation of a death by a thousand cuts, and it would be difficult to show exactly which cut caused the final demise, or whether the decision to terminate the contract was an independent decision by the broadcaster.

Secondly, defendants may try to argue justification, perhaps in terms of general societal norms against offensive conduct, or in terms of specific provisions in McIntyre’s contract (as noted above, we don’t know the terms).

However, if McIntyre could establish liability he could perhaps obtain an injunction restraining SBS from sacking him, or obtain damages from those who called for his sacking, reflecting the income and opportunity lost as a result of the cancellation of the contract, and perhaps aggravated damages for distress flowing from the cancellation. It is worth noting that courts in England, Australia and the U.S. would be less inclined to force SBS to rehire McIntyre in the event that the contract had already been terminated. Courts are reluctant to force people to work together once relations have broken down, although there is some Australian authority to the effect that the situation is different where an employee seeks an injunction against an employer.

Fundamentally, we have to stand against social media mobs who call for a person’s sacking simply because the person was offensive. Employers must make a measured decision on the basis of the legality of the situation. I’m not saying that a person can never be sacked on the basis of being offensive on social media (sometimes it is clearly right that a person is sacked), but I am saying that we should resist mobs and think about the position of the employee dispassionately. Private law may help us to challenge employers who buckle at the first sign of anger on social media; it encourages a measured view of disagreements.

We do not want a society where self-help becomes dominant, because in such a society, decisions are made in anger, and almost always result in some level of injustice. Moreover, it is bad for society if we cannot freely exchange ideas. Unfortunately, being open to different ideas means that sometimes you get offended.

When in legal practice and at law school, I was trained always to look at the other side’s argument and to take its merits seriously. This meant that I gained a better idea of the strengths and weaknesses of my own position. Sometimes it was unpleasant and uncomfortable to have my views challenged, but I grew and learned as a result, and sometimes I even listened and changed my mind.

This article represents the author’s views and not the views of her employer.