Long Read

What Is the Tribe of the Anti-Tribalists?

Considering some of the sobering political implications of tribalism might do more to loosen its grip on the tribalists than would more anti-tribalist rebuttals.

Near the end of a much-discussed podcast in May entitled Identity & Honesty, Sam Harris and Ezra Klein have the following telling exchange:

Ezra Klein: You have that bewildering experience because you donʼt realize when you keep saying that everybody else is thinking tribally, but youʼre not, that that is our disagreement.

Sam Harris: Well, no, because I know Iʼm not thinking tribally—

Ezra Klein: Well, that is our disagreement.….Right at the beginning of all this with Murray you said you look at Murray and you see what happens to you. You were completely straightforward about that, that you look at what happens to him and you see what happens to you.

Sam Harris: Itʼs not tribalism. This is an experience of talking about ideas in public.

Ezra Klein: We all have a lot of different identities weʼre part of all times. I do, too. I have all kinds of identities that you can call forward. All of them can bias me simultaneously, and the questions, of course, are which dominate and how am I able to counterbalance them through my process of information gathering and adjudication of that information. I think that your core identity in this is as someone who feels you get treated unfairly by politically correct mobs.

Here, in this standoff, we can see the alternative universes of the tribalist and the anti-tribalist. Klein wants to play identity politics—he wants to get Harris to admit that he is part of a tribe too. Harris does not want to play the game of identity politics—he wants Klein to agree to approach social issues from a standpoint that is independent of identity. He wants Klein to argue from a neutral perspective—from something that is like what philosopher Thomas Nagel calls “the view from nowhere.” Klein denies that such a stance exists and thinks this is just a way for Harris to avoid revealing the biased identity from which he speaks—his tribal perspective. Harris clearly sees himself as seeking common ground, but it does not seem that way to Klein.

I approach this exchange with a strong preference for Sam Harris’s stance. I think a rational, empirical, universalist approach to argument is the best perspective to adopt when discussing social issues. I wish the tribalists would not frame issues with the perspective and interests of their own tribes as their central focus. So what is an anti-tribalist to do when faced with a tribalist who refuses to argue in any other manner? I cannot add anything original to the long list of arguments that anti-tribalists have made in attempts to get tribalists to abandon their approach. The advantages of scientific, rational thinking on social issues have been argued by others, and convincingly, in my view. The Harris/Klein exchange shows that what results from these attempts, however, is the mutual incomprehension that occurs when a decoupler meets a contextualizer (see Falkovich in Quillette).

I wish to try a different approach here. Rather than create another argument in favor of anti-tribalism, I hope to prod tribalists to think a bit more about what might happen if the anti-tribalists ever capitulated. What would happen to the political prospects of advocates of identity politics if the anti-tribalists were ever to throw in the towel and agree to play the identity politics game? Considering some of the sobering political implications of tribalism might do more to loosen its grip on the tribalists than would more anti-tribalist rebuttals.

“OK, You Win”: The Anti-Tribalist Picks a Tribe

In the Harris/Klein exchange, Klein is the advocate of identity stances (AIS), and Harris is the opponent of identity stances (OIS). What if, instead of presenting the umpteenth (usually unsuccessful) argument against tribalism, the OIS reversed course and said: “OK, I’ll do it. I’ll explicitly adopt an identity perspective. I’ll name my tribe and argue from its perspective. My tribe is: the citizens of America for whom their identity as a citizen is more important than any identity that derives from demographic categories (race, sex, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, SES, etc.). I will call this tribe: Citizen American, or C-Amer for short.”

Many of the arguments that advocates of scientific rationalism wish to make for their approach to social issues would suffer little distortion if made instead from an admitted C-Amer perspective—a perspective where the focus is on the individual (citizen) identifying at the national level (American). This last assertion may play out differently (and be more or less easy to implement) from different places along the ideological spectrum. It will certainly be true that a Republican is more likely to be in a position to easily adopt a C-Amer identity if forced to play the identity politics game by an AIS (see my earlier essay in Quillette). But in addition to many Independents, there might be Democrats as well who could easily adopt the C-Amer stance. For example, Bernie Sanders’s campaign was less focussed on identity than was Hillary Clinton’s, and that may well be true for many of his supporters. It is likely that, rather than identity politics, many of his supporters were attracted to a more universal message of economic justice for American citizens. Sanders himself has expressed concern about the possibility of immigration and globalization depressing American wages. He was less of a globalist than Clinton, and Sanders only belatedly embraced group identity politics when it became clear that that was a necessary strategy in a Democratic primary. Thus, among Sanders supporters are many who, if forced to play the identity politics game, could comfortably declare C-Amer.

The Democratic party may contain many other subgroups whose worldviews are not far from C-Amer. Certainly many Democratic intellectuals such as Mark Lilla in his book The Once and Future Liberal (2017) have gone public with trenchant criticisms of identity politics. They must represent a subgroup of Democratic voters who are tired of the identity game and would prefer not to play it but, if forced, would find C-Amer a not uncomfortable stance. They remain Democrats in order to support a variety of specific issues (abortion, gun control, etc.), so their revealed voting behavior may conceal their opposition to identity politics.

Additionally, the now defunct Daniel Patrick Moynihan/Scoop Jackson wing of the party shows that there was once a substantial C-Amer representation among Democrats. Although this wing is now diminished in terms of formal party officeholders, there must be many Democratic voters who would express the C-Amer identity of this wing if forced to choose an identity stance. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, many Independent voters would already be voting more consistently for Democrats if not for their intense dislike of identity politics. Attempts to flush out their identity, as Klein does with Harris—attempts to force them to play the identity game—may send large numbers of Independents to C-Amer (perhaps even more so after Donald Trump leaves the scene).

Bringing in the case of Independent voters reveals the electoral danger of the game that Klein is playing with Harris—the game of forcing a person to declare their identity bias so that it can be discounted or privileged according to the rules of intersectional doctrine. Forcing previously non-identifying Americans into a game they didn’t want and having large numbers of them (Republicans, Sanders voters, identity politics critics, Jackson/Moynihan Democrats, Independent voters) choose the C-Amer identity might not be the best outcome for the Democrats. This large (empowered) group of C-Amers might decide that they will not have their opinions devalued according to the group calculus of identity politics. And here is a key point that the AIS who is insisting on this game often forgets:

The Identity Left May be Able to Dictate the Game, But They Can’t Dictate How the Other Side Plays

Here, I am glossing the next step in my thought experiment. The first step was illustrated by the Harris/Klein podcast transcript (AIS to OIS: “You have an identity bias, you just won’t admit it”). My imaginary step 2 was, OIS to AIS: “OK, you’ve forced me to play. My identity is C-Amer.” I am conjecturing here about the third step, AIS to OIS: “That is not a valid identity.” In short, we are at the point in the AIS/OIS game where the AIS objects that C-Amer is not a valid group in the identity politics game; that it is not a demographic category or even a set of conjoined demographic categories like high-SES, educated, white male intellectual (the kind of identity that one gets the feeling Klein wants Harris to choose).

This objection is unfounded. What the identity-politics Left has failed to appreciate is that they don’t have the right to assign an identity to their opponents. Yes, like Klein, an AIS can refuse to allow an OIS to deny an identity perspective—and then refuse to participate if the OIS does not declare one. An AIS is free to say that an OIS must declare an identity bias. But the AIS does not get to assign that identity bias. Open-mindedness on the part of an OIS who agrees to speak from an identity perspective does not necessitate letting the AIS dictate an identity perspective for the OIS. Many AISs act as if they have that right, thus revealing the authoritarian edge concealed behind the social justice façade.

Take, for example, Jake, who is a 12 year-old who wants to start up a game of basketball. His friend Rick wants to organize a game of football. Rick is more adamant, so Jake gives in and agrees to organize a game of football. They are the captains of their respective sides, choose up their teams, and get ready to play. But when the game starts, Rick does not get to call the plays for Jake’s team. Jake has agreed to play Rick’s sport, but Rick does not get to dictate how Jake’s team operates once the game begins. The AIS who wants to assign the identities of others is acting like Rick—if Rick demanded to call the plays of the opposing team who had reluctantly agreed to play his sport in the first place.

An attempt to prescribe the identities of others is behind the campaign to label as ‘white privilege,’ ‘white supremacy,’ and ‘white nationalism’ any argument and person who remotely challenges the shibboleths of left-wing identity politics. This is transparently an attempt to discredit any stances that level criticisms of progressive policies or movements. Any conceptual identities outside of the intersectional victim categories of the Left will be labelled ‘white’ and thus associated with ‘white supremacy.’ The arguments of this stance will therefore not have to be addressed because they will be tainted from the beginning.

The C-Amer stance is a threat to this strategy because it is an open identity group defined by ideas rather than by demographics.1 It is open to all races, sexes, religions, genders, ethnicities, etc. And unlike the bullying logic of identity politics, you can freely choose it or reject it. C-Amer can’t claim your membership unless you agree to join. In progressive politics, you are classified as part of a traditional victim group just by being born with a certain demographic profile. Identity politics does not care that you didn’t sign up to be part of an identity category based on victimhood. Jamil Jivani in Quillette objects to the pre-prescribed opinions for minorities in the left-wing political nexus: “New voices from these communities that have entered the conversation in recent years—including me—have a role already prescribed for them in Kleinʼs boxed-in take on identity politics” and argues that it is Harris who honors the individuality of minorities by “implicitly fighting for the right of others ‘who do not look like’ him to be treated as individuals, not ambassadors from a group.”

It is doubtful that the one in four Hispanics or the one in four Asians who voted for Donald Trump want progressive advocates to be speaking for them, yet the AIS blithely articulates attitudes for entire demographic categories without consulting the individuals within them. The AIS wants to assign you to a tribe and then dictate that the beliefs of the entire tribe are uniform. C-Amer does not do this.

As an open, freely-chosen stance not tied to demographics (other than citizenship, resident status, or prospective citizenship) C-Amer can be honestly and firmly employed against identity politics and against AIS attempts to taint opponents with baseless charges of racial animus. By ‘firmly,’ I mean that C-Amer advocates can adamantly and honestly repudiate the claim that C-Amer is a proxy for a demographic category (be it race, sex, income, etc). Of course it will be correlated with demographics in a host of ways, but the correlations do not define it.

The Mathematics of Identity: Why There Will Always be an Association with Majority Status in Any Anti-Tribal Group (Until Identity Politics is Defeated)

The fallacy of the charge that opposition to identity politics is fuelled by white nationalism results from a failure to understand the math that follows from identity politics already being in place in the Democratic party. It is necessarily the case that any opposing identity will have an association with non-minority status (whiteness, in our culture) until identity politics is defeated. But this necessary association is often unrecognized, and instead the correlation is often used to sow suspicions of racism against any opposing perspective (via the accusingly delivered phrase “but it’s associated with whiteness!”).

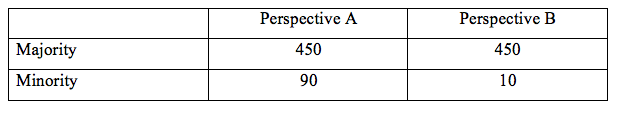

Let’s consider a thought experiment in order to see that it is redundant and banal to say that some characteristic is “associated with whiteness” when it is guaranteed to be correlated once minorities cluster. The thought experiment is deliberately and knowingly stripped of context and history so that we can focus on the logic of the numbers in play. Imagine a population of 100 minority individuals and a majority of 900 individuals. Imagine that there existed a perspective (or a stance, or a political party, or a worldview, or an ideology—it doesn’t matter which), let’s call it A, and that 450 majority individuals and 90 minority individuals were originally attracted to it (a total of 540). A total of 460 people (450 majority and 10 minority) were not attracted originally to perspective/party/ideology A.

Now imagine that an alternative perspective/party/worldview, call it B, comes along and attracts the remaining 460 people (the other 460 are candidates for B, because if A had been optimal for them, they would already be part of it). The situation would look like this:

The majority doesn’t cluster. It is equally attracted to perspective A and perspective B. The minority group in this population does cluster. As a result of that clustering, demographic group (majority vs minority status) is correlated with perspective. In fact, there is a statistic—the phi coefficient—that measures the degree of association in a 2 x 2 table like this. The degree of association between demographic group and perspective here is .241, which sounds, and is, moderate to low considering that the coefficient runs from -1.0 to +1.0. The value of the phi coefficient sounds less startling than saying that 97.8 percent of perspective B individuals are in the majority population (450 out of 460), which is also true. But then again, the 97.8 percent itself sounds less startling when taken in the context of the fact that fully 83.3 percent of perspective A individuals are also in the majority group (450 out of 540). In this example, perspective B is majority dominated not because the majority uniformly takes a particular stance, but because minorities are pretty monolithic in their perspective choice.2

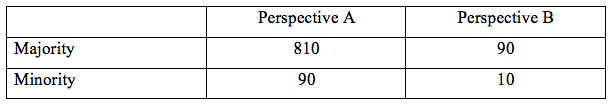

The only way that perspective B would not be correlated with demographic status is if, when given the choice, only 100 of the 460 opted for perspective B (90 majority and 10 minority individuals) and the remaining 360 decided that they really did like perspective A better. Then we would have:

…and the phi coefficient would become zero (indicating no association between perspective and majority/minority status). Majority status would no longer be associated with perspective B. But this is achieved by the majority becoming as monolithic in perspective choice as the minority is. One way for opponents of Democrats to avoid the charge of “being associated with whiteness” is for most of the opponents to become Democrats! (Might there be a tactic at work here?) Finally, another way for the phi coefficient to be zero is for 40 individuals in the minority in Example #1 to defect from perspective A to perspective B.

The point of this abstract exercise is to see that, whatever perspective arises in opposition to perspective A, it will be associated with majority status. In the context of identity politics, it means that whatever philosophy arises in opposition to identity politics, it is going to be “associated with whiteness!” because the lopsided baseline was already in existence.

We now have the fourth step in the imaginary confrontation between the AIS and OIS with which we began:

- AIS: “You’re in a tribe too.”

OIS: “No, I’m not.” - AIS: “Yes, you are. You speak from some perspective bias.”

OIS: “OK, I am in a tribe. I’m in the C-Amer tribe.” - AIS: “That’s not a valid tribe.”

OIS: “You don’t get to assign everyone else’s identity.” - AIS: “OK, you’re a C-Amer. But it’s disproportionately non-minority. Your tribe represents white supremacy.”

The OIS response to this fourth step is to point out that white is not a defining feature of C-Amer and it is only incidentally correlated with C-Amer because identity politics had already started the game with lopsided percentages.3 The statistical exercise of this section was to diffuse the invalid racism charge from AIS and turn one’s response from the invalid, unthoughtful “Oh my gosh, it’s correlated with whiteness!” into “Of course its correlated with whiteness, but whiteness has nothing to do with it.”4

The Perils of C-Amer for the Democratic Electoral Strategy

As Mark Lilla’s book amply demonstrates, the people playing the identity politics game are playing a different game to those in the Democratic party who are trying to win elections. No doubt the AIS thinks they are helping the Democrats electorally by flushing out groups like white nationalists—by forcing them to play the identity politics game (as if they weren’t already). Since white nationalists are pretty uniformly loathed and more easily associated with the Republicans, the idea here is that this kind of identity-outing helps electorally. But identity politics has the potential to flush out identities that are not so electorally helpful to Democrats. The argument here is that C-Amer is one of them.

The C-Amer identity is open ended. It could in theory be chosen by all American citizens and prospective citizens, unlike the demographic categories that identity politics uses to slice and dice the electorate. Unlike C-Amer, Democratic identity politics seals off others when it separates out victim groups, implicitly (and often explicitly) labelling the complement of the group—white, or men—as oppressors.5 This is not a wise electoral strategy when the complement category is half the electorate (men) or more (white). And, on top of that, there is the issue discussed above—the tendency to treat all members of the designated victim groups as if they thought alike. As Jamil Jivani puts it, “The phenomenon can be anti-democratic in its effect, because it enables the most vocal members of an identity group—or those, such as Klein, who claim to be channeling a single viewpoint attributed to that identity group—to speak for others without democratic accountability.”

This is presumptuous even when the designated victim group votes 90 percent Democratic, as in the case of African-Americans. It is downright insulting when the group splits closer to 66-33 percent Democratic, as do Asians and Hispanics. And it is insulting not just to the one in three who do not agree with the AIS dictating their identity to them, but it is potentially uncomfortable for even the majority if they are conscious of the views of the dissenters. The AIS may have gotten my identity exactly right, the majority might think, but it still chafes when he acts as if he has the right to assign it.

The illogic of victim identity categories reaches the lunatic level when applied to a category such as women, where the split is as close as 55-45 percent. It is ludicrous to speak of a category that splits 55/45 as if there is uniformity within it. But this was done prominently during the 2012 campaign when the Democrats accused the Republicans of waging a “War on Women.”

The variability and fissures within the women’s vote are predictably as vast as one would expect in a demographic category that large. As an example of these fissures, consider that although minority women voted strongly for Clinton (82 percent to 14 percent), white women favoured Trump over Clinton by a clear margin (52 percent to 43 percent), and white married women displayed a margin for Trump (roughly 60/40) that is similar to the split of Hispanics for Clinton, one of the traditional victim groups of identity politics. Probably many of these women preferred C-Amer (even without the name) because they didn’t see the War on Women that the Democrats were selling as a defining feature of the country. Instead, they identified as free and equal citizens, something closer to C-Amer. They saw, not an enemy within (evil men conducting a war on women), but a flexible and tolerant nation working hard to remedy legal and cultural flaws.

An AIS flushing out women who identify as C-Amer will reveal that the Democratic strategy of claiming that all rational women vote for them is an aggressive shaming tactic. Almost half of all women reject this view now. There could even be more if a labelled, freely-chosen identity like C-Amer were available to them. Women are the case where the strategy of identity politics is most starkly revealed: AIS wants to assign you a tribe and then uniformly dictate the beliefs of that tribe. C-Amer does not do this.

Scientific Thinking Versus the Identity Approach to Knowledge

The lure of identity politics is that in exchange for following the group victim narrative, you get a special privilege—the privilege of a superior position in any discussion that concerns your assigned group. Mark Lilla points out that the phrase “speaking as an X” is really a claim of privileged position in the debate, one that frames the debate as “the winner of the argument will be whoever has invoked the morally superior identity” (2017, p. 90). The spectre of argument descending to such premodern levels was probably what made Harris so recalcitrant in the exchange with Klein. No doubt Harris was pressing (rightly, in my view) for an argument where no one claims special privilege. Harris wants both parties to take the stance “speaking as a rational human being,” so that their arguments can be evaluated on their merits without invoking special scoring points for characteristics over which we have no control (race, sex, etc.).

But in the face of AIS resistance to declaring a mutually neutral stance—in the face of being forced by an AIS to play the identity politics game—the C-Amer stance is one of the best places for people (like myself) who share Harris’s proclivities. C-Amer does claim some privilege in the identity politics game, but very, very much less than others are claiming. It is much closer to the scientific rationalist ‘view from nowhere’ that Harris is defending on the podcast. And it shuts no-one out from claiming it as their own stance, unlike identity politics, which does. In normal identity politics, a man can’t claim the ‘speaking as a woman’ privilege. But, for purposes of argument, almost anyone can adopt the C-Amer perspective. That is, a non-C-Amer could say, “well you have no special right to C-Amer, I can choose it too and claim the privileges of its framework.” Unlike the monolithic stance of a traditional player in the identity politics game, the C-Amer can show the expansiveness and inclusiveness of the perspective by inviting an opponent to do just that and fairly allowing him/her to argue from that position.

In the 1970s, when I started teaching critical thinking and scientific thinking in a psychology department, it was the epitome of the professor’s role to teach students to think like Harris wants Klein to think—to teach students the counter-intuitive superiority of ‘the view from nowhere’ implicit in the scientific worldview and the pitfalls of relying on ‘lived experience’ to adjudicate knowledge claims. My students and I discussed how, in science, the truth of a knowledge claim is not determined by the strength of belief of the individual putting forth the claim. In my courses, we discussed the problematic nature of adjudicating truth claims by other means; for example, though intuition, authority, or personal experience (as we called it then). The problem with all non-empirically-based systems of belief is that they have no mechanism for deciding among conflicting claims. When everyone’s claim is based on lived experience, but the claims conflict, how do we decide whose lived experience is reflecting the truth? History shows that the result of such conflicts is usually a power struggle.

Rather than relying on personalized knowledge, science makes knowledge claims public so that conflicting ideas can be tested in a way that is acceptable to all disputants. Science puts observation in place of a power struggle. Truly scientific claims are in the public realm, where they can be criticized, tested, improved, or perhaps rejected. This allows a selection among theories to take place by peaceful mechanisms that we all agree on in advance, and it is why science has been a major humanizing force in human history.

In the course of all these discussions, as a voluble new instructor back in the 1970s, trying to direct my students’ attention to the importance of the material, I’m sure that, gesticulating, I exclaimed, “Science doesn’t care about your personal experiences, it doesn’t care about your feelings!” It got the students’ attention. Now, I’m sure that a student would hear that I was denying the meaning of their personal experiences and say that they had been triggered. It would probably lead to a visit from the Bias Response Team and I would be writing memos back to the Dean explaining myself, rather than writing this essay or doing my research.

Ironically, in the 1970s, it was seen as politically progressive to move students from personalized worldviews to scientific worldviews—to move students from egocentric perspectives to ‘the view from nowhere.’ The warning that Harris gives Klein in the podcast (at 2:10:58)—“I am just saying that we are going to be ambushed by data that will have a political charge and we have to be in a position to talk about it without demonizing people”—was taken to heart back then. The larger assumption was that revealing the objective truth about the human condition (biologically and psychologically) would aid in constructing a just society, not impede it. This mindset has been lost in the modern university.

A robust defence of the scientific adjudication of truth claims is no longer the default—no longer the accepted norm—on university campuses, at least as exemplified in the official policies coming from the university administration and in the politically-correct atmosphere in which professors in the social sciences and humanities must now work (making groups like Heterodox Academy necessary). The new normal is what Harris experienced with Klein. Universities are as likely now to side with Klein. The extensive diversity/inclusion administrative infrastructure is devoted to the AIS approach, not to advancing a scientific worldview.

Identity Politics is Bad—Not Just Bad for the Democrats

As this personal history reveals, I approach identity politics from the academic side of things—not from that of a political theorist or a party operative. As a university professor and scientist, I approach identity politics slightly differently than did Lilla—also a professor—in his book. He is quite clear that he thinks identity politics is impeding the Democratic party (2016 being a salient case in point) and that for practical electoral reasons it should be de-emphasized. He (attractively) suggests (pp. 120-121) that Democrats appeal more to citizenship when addressing the electorate. All of this sounds so similar to C-Amer, that I should clarify some differences.

C-Amer was not concocted as a strategy to help the Democrats. It was inspired by the Harris/Klein exchange and the associated thought experiment of what an OIS might do in an OIS/AIS standoff. C-Amer is a strategy that could be used against a right-wing identitarian as well, with all the logic that I have discussed following through in exactly the same manner. Nothing in its use depends on the detail that Klein and Harris are both left-leaning. A right-wing AIS likewise does not get to assign an identity to a right-leaning OIS.

C-Amer was not invented as a ‘front’ for the identity politics of the Left. It was not intended to serve as a public relations ploy for Democrats in elections—one that would allow identity politics to simply carry on in the background, veiled from the public eye. I come to bury identity politics, not to give it a lifeline. C-Amer is not meant to conceal the agendas of identity politics, but to open up the space of discourse from the stifling effects of AIS intransigence and to remove the “play our game or else—we’re the only game in town” advantage that identity politics enjoys.

I am not saying that Lilla intends to conceal identity politics with his citizenship emphasis, but at times he comes close, as when he says that “it is a social fact that many Americans today think of themselves in terms of identity groups, but there is no reason they cannot simultaneously think of themselves as political citizens like everyone else” (p. 121). Whoa, there. That sounds like some people get two stances to argue from—or two sets of influences in politics—and others get only one. It sounds like we are right back at the logic of Democratic politics again, where some get their full weight as citizens like everyone else, but then get some extra weight because of the group they are in. That approach is going to take us right back to the AIS/OIS impasse again.6 In an honest use of the C-Amer stance, you don’t get to weigh in as a full and equal American citizen and then weigh in again as a member of a group—that would be like getting two votes. C-Amer is not a tool for the Democrats to use to win elections without having to give up identity politics. It is a tool for breaking the roadblock that AISs throw in front of rational discussion.

The proportion of politically affiliated citizens (Democrats, Republicans, Libertarians, Independents) who might choose C-Amer as a stance is unknown. Its electoral consequences could go either way in my view. If they used it honestly (that is, not to conceal other agendas), perhaps the Democrats could employ C-Amer to pull back from identity politics and form a natural alliance with the many Independents who abhor victim-based identity politics but are already close to C-Amer in perspective. Alternatively, perhaps post-Trump, the Republicans will realize the advantages of C-Amer and use it honestly—that is, truly inclusively (using it dishonestly will, I would hope, defeat them just as identity politics has impeded the Democrats). Like the converse coalition, a coalition of Independent C-Amer with an honest Republican version would be electorally formidable.

At the very least, I would caution Democrats against thinking that all AIS identity-outing will be helpful to them politically. That incorrect default comes from the authoritarian assumption that AIS have the power (and the right) to stipulate the identities of all others, including their opponents. Left-wing dominance of cultural institutions such as the media, universities, and Hollywood might have encouraged this aggressive assumption.

But identity-outing could backfire on the Democrats. If the Democrats persist in the identity politics game, a C-Amer coalition arrayed against them could be a formidable opponent. Post-Trump, C-Amer may have particular use as a cohesion tool for regrouping Republicans. It is already probably a major (but unnamed) framework among Independents. Old school economic liberals and union members who have decried the dominance of identity politics in their party may find it congenial. C-Amer also remains an open identification for all minorities who do not see their interests advanced by being in an ethnic silo. Finally, many young men may one day become tired of their designated role as allies in the intersectional game—a role confined to confessing their privilege and getting out of the way to give others the platform. C-Amer becomes a more dignified identity for them than their current role in an identity-based Democratic Party.

Salena Zito and Brad Todd open their book on the 2016 election (The Great Revolt, 2018) with the story of Bonnie Smith, a bakery owner in Ashtabula County, Ohio. Bonnie’s parents were Democrats, and so were she and her husband. Bonnie had voted for Democrats all her life and had worked in the Democratic sheriff’s office. Local officials in her county had been Democratic as long as anyone could remember. In the 2016 Ohio primary, Bonnie had chosen Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton. But in the general election, both Bonnie and her husband voted for Trump. Bonnie explained that she felt that she had to take a stand “for my country” (p. 4). I would bet, that if you forced Bonnie to choose an identity, it would be C-Amer, if she were aware that such an identity existed. I agree with Zito and Todd, regarding people like Bonnie, that “if their political behavior in 2016 becomes an affiliation and not a dalliance, they have the potential to realign the American political landscape” (p. 3). And if people like Bonnie are forced into an identity stance (as the AIS seems to want) this could be really bad for the Democrats.

I suspect that many Democratic operatives know this, but are taking the easy way out. The easy way out is to let their base carry on with identity politics and hope that the campaign to demonize other identity stances with the epithets ‘racist’ and ‘xenophobe’ can impede valid counter-identities such as C-Amer. But this may be only delaying the inevitable. Someone will eventually play the C-Amer card. In fact, the increasingly baseless claims of ubiquitous racism and xenophobia by progressives could make this happen sooner rather than later (calling people like Bonnie ‘deplorables’ will definitely make it sooner!). The demonization campaign of the AIS is unbecoming of Democrats, in any case. We should reject the campaign to try to shame people away from critiquing a politics of identity based largely on demographic categories rather than conscious choice.

For months, political theorists have been puzzling over the 206 counties in the United States that voted for Obama twice and then for Trump in 2016. That otherwise strange phenomenon might have been signalling the emergence of C-Amer as a political identity. If so, the phenomenon broke in favor of the Republicans this time, but this is not a guaranteed outcome. C-Amer as a political identity could aid the Democrats if it forces them to abandon the types of victim-group politics that reduce support for more universalistic Democratic policies. On the other hand, it could just as well become a cohesive identity for a post-Trump Republican party. The tribalist Democrats need to think hard about the consequences of forcing the entire citizenry into explicit identity stances. Those consequences could be more unpredictable than the Left now seems to think, focussed—as it is now—on what it assumes are inevitable demographic changes in its favor.

In short, if Klein refuses Harris’s universalism, he may succeed in forcing a lot more people to play the identity politics game. But they may decide not to play it the way he wants them to play—by labeling themselves white nationalists (and thus marginalizing themselves). Instead, they might label themselves C-Amer and gain allies from Harris-like universalists as well as from ethnic group members who want to be thought of more as Americans first. The diversity and size of a Citizen-American identity could well have unpredictable electoral consequences.

Footnotes:

1 There are many eloquent commentaries relevant to the C-Amer perspective, writings by: Richard Rorty, Shelby Steele, David Brooks, Peggy Noonan, Jason Riley, J. D. Vance, Yuval Levin, Joan Williams, Amy Chua, Jonathan Haidt, Victor Davis Hanson, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Richard Rodriguez, Greg Lukianoff, John McWhorter, and many others including, of course, Lilla’s own excellent volume.

2 I am deliberately keeping the example abstract by ignoring the history of the original partitioning of minority voters.

3 When I imply that identity politics caused the original partitioning, I am using here Lilla’s (2017, pp. 59-64) emphasis on the part of the backstory that begins in the 1960s and for similar reasons.

4 We saw an example almost ten years ago now, when the media breathlessly announced that the new Tea Party movement was “almost entirely white!” The rest of the nation reacted with a yawn, because it seemed to recognize the mathematical necessity of this fact more than the media did.

5 In fairness, the AIS counters this criticism by defining the status of so-called “intersectional ally”. We can assume that this identity of humble supplicant whose prime concern is to let others speak will not be chosen by many.

6 And it will surely encourage demands for: “everyone else to have a group too, along with citizenship”. Lilla’s description of his citizenship position here is really encouraging what we don’t want: publicly expressed allegiance to categories like white, or male, or straight.