film

Megalopolis: Bloated, Outré—and Brilliant

Like a Hieronymus Bosch painting, it’s chaos alright—but it’s a dazzling chaos.

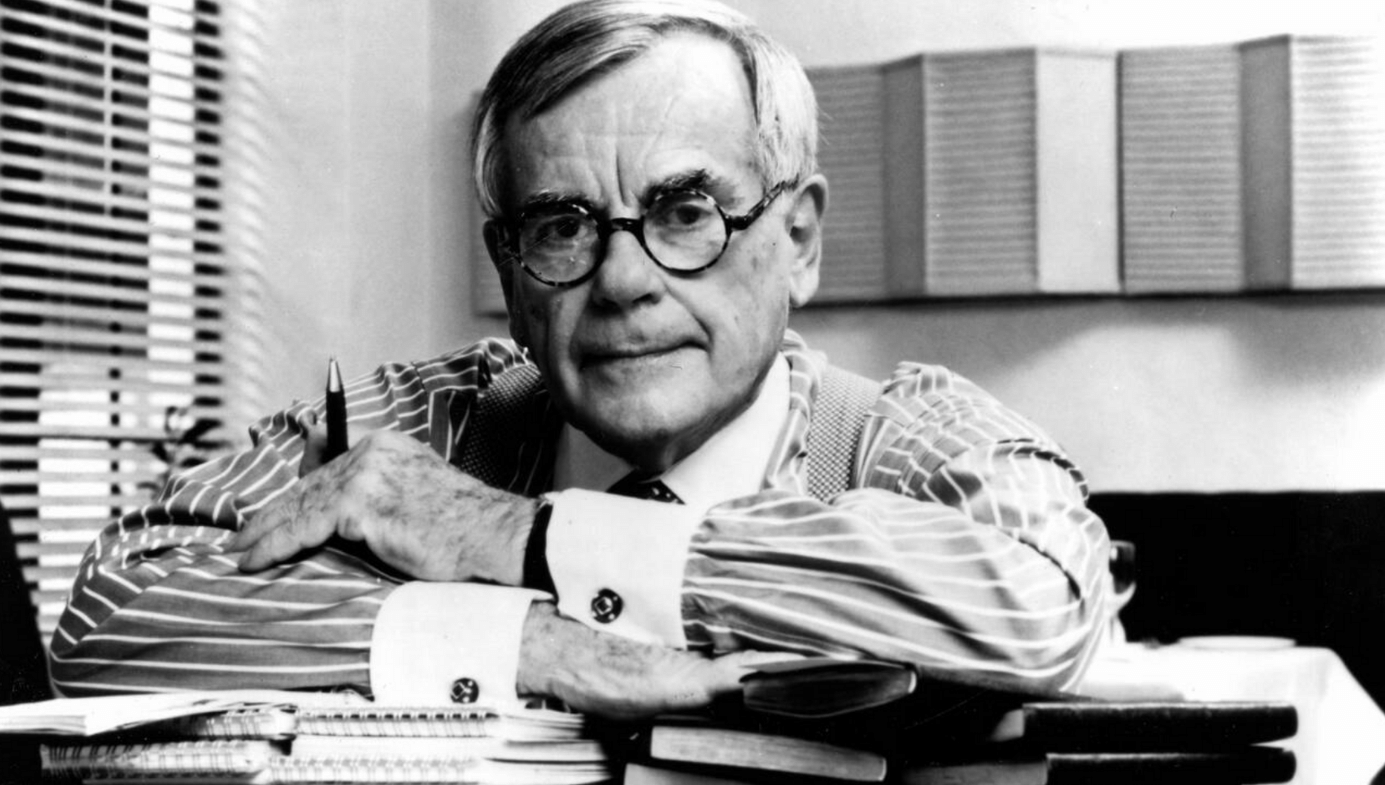

No film this year has been as anticipated, hyped up, and dreaded as Megalopolis, which will probably be the coda to Francis Ford Coppola’s august career as one of the preeminent auteurs of the past half-century of cinema. Among other achievements, Coppola has produced the greatest four consecutive films of any director: The Godfather I and II, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now, made within seven years of each other in the 1970s, during the apex of the American New Wave. However, the release of Megalopolis, which Coppola self-funded to the tune of one hundred million dollars, was certainly a sui generis event.

Mainstream critics have generally been dismissive. Peter Bradshaw in the Guardian called it a “a bloated, boring and bafflingly shallow film”; Drew Magary of The San Francisco Gate condemned it as a “piece of shit”; Bilge Ebiri of Vulture labelled it “absolute madness.” But Megalopolis is certifiably not a “piece of shit.” The cinematography is sometimes impressive and, at its best, the film is experimental and thought-provoking. As the title suggests, it is a fable that uses a combination of history, mythology, and art to produce social commentary on our current moment.

But, while it may not be shit, the movie is certainly no masterpiece. It has its fair share of longueurs and unnecessary digressions. The dialogue is often awkward, fusing present-day English with Shakespearian soliloquys, while attempting to remind the audience of the Roman setting by chucking in some Latin along the way, such as the invocation of Brutus, John Wilkes Booth style: “sic semper tyrannis.” And it is often self-indulgent. The filming process seems to have been chaotic, too—anecdotes from the set suggest that Coppola’s approach was messy: new ideas were trialled on set as he went along, meanings and characters were constantly changed in ways that must have made consistent performances difficult for the cast. There are moments—such as the goofy attempt to disguise an arrow as an erection towards the end and the awkward love scene between Wow Platinum, played by Aubrey Plaza, and Clodio, played by Shia LaBeouf, as they’re plotting a hostile takeover of the national bank—at which the gap between what was intended and what was released is palpable.

Moreover, Coppola, now an octogenarian, may be a genius with an imperishable legacy, but he hasn’t made a hit movie—or indeed any film of note—in decades. Coppola has always been a gambler. Sometimes these risks have paid off—as when he took a chance on Marlon Brando, an actor whose popularity was on the wane, and on the then-unknown Al-Pacino on The Godfather; and when he opted for a tortuous and exorbitant production process when filming Apocalypse Now. But at other times, his gambles have backfired—as in the case of One from the Heart, which almost bankrupted him. In this sense, he is reminiscent of Robert Altman: a towering director with a messy filmography filled with classics, flops, and a lot of other stuff in between.

Megalopolis is not The Godfather or Apocalypse Now. Yet, it is assuredly not as bad as One from the Heart, which is among Coppola’s worst films. It has obvious deficiencies: Shia LaBeouf’s wooden acting; the protagonists’ lengthy and frankly tedious hallucinations; the mawkish sentimentality of some scenes; the random cuts in others. Nevertheless, Megalopolis is uncommonly bold and skilfully crafted. Like a Hieronymus Bosch painting, it’s chaos all right—but it’s a dazzling chaos.

The film takes place in a retro-futuristic New Rome, which features many of the landmarks of New York City, in a decadent empire plagued by political corruption, a gluttonous ruling class, and intractable social decay—there is clearly an allusion here to the present-day United States: the Rome of our epoch. The hero of the tale is Cesar Catalina (played by Adam Driver), an idealistic, visionary architect, a Howard Roark type, who won’t abide by any conventions other than his own. He doesn’t even need to respect the boundaries of time, since he possesses a Neo-like ability to suspend it at his pleasure. He invents a revolutionary new resource, Megalon, for which he wins the Nobel prize, and which he will use to build a utopian city-within-a-city, Megalopolis, to help rejuvenate a dilapidated New York ravaged by a comet. His antagonist Franklyn Cicero, played by Giancarlo Esposito, is a conservative liberal, who represents order and pragmatism, whom Catalina calls a “slum lord.” He is suspicious of Catalina’s project, fearing it is merely a ruse to disguise a power grab by a man drunk on delusions of grandeur. Catalina calls it Megalopolis, he quips, because “that’s the closest he will get to Megalomania.” Instead of making things better, Megalopolis, he believes, will simply ignite chaos.

Those familiar with classical history will recognise the allusion to the Catilinarian conspiracy: a failed putsch of 63 BC, led by Lucius Sergius Catilina, who attempted to seize the Roman consulship from his rivals, who included the philosopher and statesmen whom we know as Cicero. One of Cesar’s other opponents in the film is his envious, conniving, gender-fluid cousin, Clodio Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf), who tries to rally the people against his cousin to satisfy his own lust for power. The conflict becomes more complicated when Catalina—who is already embroiled in an affair with the ambitious newscaster Wow Platinum (played by Aubrey Plaza)—becomes romantically enthralled with Cicero’s socialite daughter, Julia, portrayed by the fetching Nathalie Emmanuel. Julia is disillusioned with her father’s obstinate conservatism and believes that Catalina’s project is not only necessary but could lead to a better way of life.

Not all is as it seems, however. Catalina envisages creating a techno-utopia in which form and function are integrated and beauty is matched by plenitude. But that project necessitates the demolition of existing neighbourhoods and the displacement of their already economically disenfranchised residents. This is a quintessential example of the dialectic of creative destruction, as described by Joseph Schumpeter, in which old innovations are replaced by new ones in ways that are necessarily destructive—a dynamic that has been crucial to modern civilisation and capitalism from the very beginning. We see this in Goethe’s Faust, in which the old peasant couple Philemon and Baucis are killed so that Faust can take over the land on which their cottage stands and use it to accomplish his own grand projects. “Their stubbornness, their opposition, ruins my finest acquisition,” Faust angrily complains (in David Luke’s beautiful translation). “Why then scruple at this late hour? Are you not a colonial power?” Mephistopheles encourages. “Well, do it!” Faustus tells him. “Clear them from my path!”

The name “Cesar Catalina” is Coppola’s clumsy way of signalling that his protagonist is both a tyrant and a failed revolutionary. Indeed, many revolutionaries end up becoming tyrants themselves and rationalising atrocities in the name of “historical necessity.” But Catalina is also just another technophile capitalist who discovers a supposedly game-changing technology that he hopes will make him stinking rich, after which he talks up a good game about “progress” and begins to believe that he and he alone will save society—although his utopian schemes are just a ploy to gain political power and perpetuate the cycle of capital accumulation. We get some intimations of Catalina’s megalomania in a scene in which he addresses the multitude, which is intercut with images of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

The demos of New Rome, meanwhile, are presented as an ignorant and vicious canaille. They don’t understand that the construction of Megalopolis would serve their own interests, and are easily manipulated by demagogues like Clodio, who pretends to be a populist advocate of the downtrodden in order to seize power in the game of musical chairs that is the power struggle between the members of the ruling class of New Rome. Everyone of note in the film is part of that ruling class and longs to be an enlightened despot, uplifting the working class, fighting on their behalf. The working classes themselves, however, can’t be allowed to represent themselves politically.

Towards the conclusion of the film, Cesar and Cicero have an argument about the desirability of utopias: Is radical societal change possible or, indeed, desirable? If so, how can it be achieved? Is it worth taking the risk of abolishing our current society and erecting a new one whose implications and consequences are unknown? This is an argument that dates back at least to Thomas Paine’s and Edmund Burke’s disagreements over the French Revolution. The present state of affairs may have numerous problems that have to be addressed somehow—yet there is always the danger that the proposed cure may be worse than the disease. Society is crumbling and they have duty to bequeath future generations a better world than the one they inhabit: a world free from corruption and conflict. Yet, as Cicero warns, “Utopias turn into dystopias”—even those who truly believe they are saving society can enact a process that will produce dire consequences.

Indeed, idealists and utopians on the Left often misunderstand conservative and liberal objections to revolutionary schemes. It’s not that the opponents of socialism or any other utopian ideology don’t want people to have good things, out of spite. They just don’t think that socialism is possible, given what they see as our natural human limitations. Any attempt to construct a utopia will not only end in failure but will make things even worse than they were before. The danger that hard-won civic freedoms may be extinguished in the process is not worth risking. So, any change or improvement should take place within the confines of the present structure of society. One of the virtues of Megalopolis is that neither side of this argument is caricatured or demonised. We see that both conservatives and revolutionaries are motivated by complex, yet understandable considerations. One can empathise with both Catalina’s and Cicero’s positions.

The more fundamental question the film addresses is whether America can retain its superpower status or whether the empire will fall. Empires, by their nature, are transient. Yet the message of Megalopolis is that decline is neither inevitable nor irreversible and that when we look at all that mankind has already built and accomplished, we should not underestimate mankind’s capacity to manifest even the most ambitious dreams.

The final frame of the film is a title card that alludes to and expands on the American pledge of allegiance. It reads: “I pledge allegiance to our human family, and to all the species that we protect: one Earth, indivisible, with long life, education and justice for all.” Tellingly, the first line of The Godfather is “I believe in America”—and Coppola does believe in America, or at least in the idea of it. He believes in it as a declaration of the potential of mankind.

Megalopolis suggests that, though the perfect society may elude us, we owe it to ourselves and to future generations to grasp the future and make it great. The film begins as a cautionary tale, but it ends with a powerful, uplifting—and perhaps final—message from a great artist. In an artistic climate defined by safetyism, an outré film like Megalopolis should be welcomed, despite its blatant deficiencies and the likelihood that it will prove a financial as well as a critical disaster. It is an experiment worth watching. Not all experiments succeed—indeed, most fail—but without experimentation, there can be no progress, whether social, economic, or artistic.