Culture Wars

Epstein Mania on the Digital Borderlands

The longevity of the Epstein story owes less to new facts of criminal conduct than to its symbolic utility in alleging deviancy.

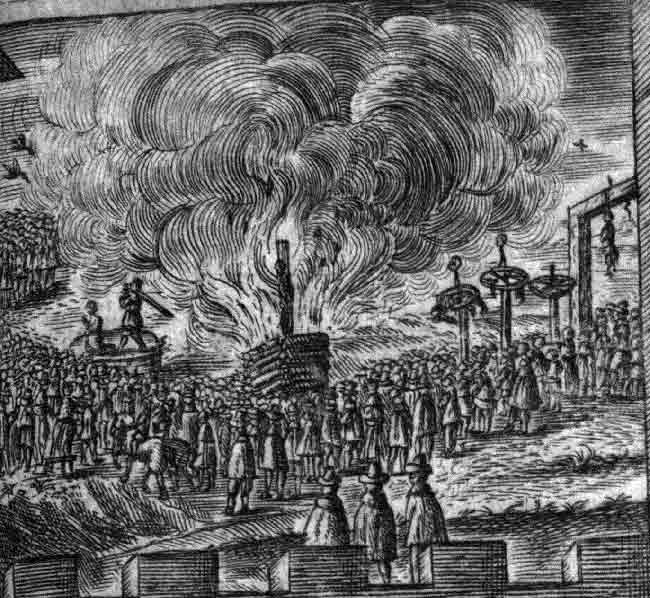

In 1628, the Chancellor of Bamberg, Johannes Junius, was charged with witchcraft. At first, he was interrogated by prosecutors without torture. He did not confess. Then he was subjected to thumb screws and leg screws. He still did not confess. Only after repeated sessions of agony did he finally admit to crimes he knew he had not committed.

A special Witch Commission had been established in Bamberg, and it was illegal to criticise its activities on pain of whipping or banishment. Those accused were tortured until they confessed, and then tortured again until they named accomplices. Under pressure, working-class people began naming the town’s elites, which meant that Bamberg’s clerical class, officials, and public servants soon found themselves imprisoned and executed. The Bamberg trials became one of the largest witch persecutions in Europe, claiming between six hundred and a thousand lives. Victims were beheaded and sometimes burned alive.

Writing to his daughter from confinement before his execution, Junius described the logic of the system he had fallen into: “Innocent I have come to prison, innocent I have been tortured, innocent must I die. For whoever comes into the witch prison must become a witch or be tortured until he invents something out of his head.”

The witch trials of Europe have long puzzled historians. People had believed in witches throughout the premodern period, but witch trials had been isolated and rare events. Why, then, did trials erupt with such ferocity in the 17th century? Why did they claim so many victims? And why were they clustered in regions like Bamberg, Trier, and Würzburg, but not in larger cities? Explanations including misogyny, famine, and disease have been proposed but rejected by historians as insufficient. The most compelling explanation focuses on the exact places the witch trials occurred, and the social function that they served.

The trials occurred most often in the borderlands between Catholic and Protestant regions, territories in which religious authorities had to compete for the loyalty of their flocks. In the borderlands between France and Germany, villages that were Catholic and Protestant were walking distance from one another. Religious leaders, anxious that their followers may defect to a neighbouring Church with a different confessional, persecuted witches to display their moral authority and demonstrate that their Church could protect people from Satan. In other words, witch trials served as a form of marketing during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation.

Economists Leeson and Russ write: “Similar to how contemporary Republican and Democrat candidates focus campaign activity in political battlegrounds during elections to attract the loyalty of undecided voters, historical Catholic and Protestant officials focused witch-trial activity in confessional battlegrounds during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation to attract the loyalty of undecided Christians.” In places where one faith dominated, such as Catholic Spain, witch trials didn’t happen (heretics were persecuted by the Inquisition instead). But where belief was contested in the borderlands between France and Germany, theatrical displays of moral authority became essential. The witch hunt was never really about rooting out evil, it was about signalling power and moral legitimacy.

Our conflicts today are for the most part no longer eschatological. Yet the mechanics of moral panics have not changed. They still emerge where authority is in flux, and they still serve as a means of asserting moral power and legitimacy. Today’s borderlands no longer exist between France and Germany. They exist online, in digital space. Platforms such as X, Reddit, Rumble, and YouTube function as modern zones of religious warfare, where rival moral sects compete for allegiance and loyalty. It is within these digital borderlands that contemporary panics erupt.

In the United States and across the Anglosphere, during #MeToo, the campus rape hysteria, and the 2020 panic about police brutality following the death of George Floyd, the progressive Left asserted its power and moral authority. In each case, innocent people were caught in the frenzy. But as Leeson and Russ write of 17th-century religious conflict, “the prodigiousness of Catholic suppliers’ witch-trial campaigns in religiously contested regions put pressure on neighbouring Protestant suppliers to step up their own.”

After Charlie Kirk’s assassination, a panic driven by the Right emerged, which also swept innocent victims into its net.

Rare are the panics that are driven by both the Left and the Right, but the Epstein story has become one.

Although investigations by law enforcement have produced only two convictions—Epstein himself and Ghislaine Maxwell—and although journalists like Michael Tracey, Matthew Schmitz, and Mark Hoffer have dismantled much of the mythology surrounding the case, the story has remained politically useful as a tool to prosecute enemies. On the Right, it is deployed to implicate figures like Bill Clinton, Bill Gates, and “the Jews.” On the Left, it becomes a vehicle for attacking Donald Trump, Zionists, and the Patriarchy. (It has also proved commercially useful to media organisations, which have leveraged public fascination for clicks and subscriptions.)

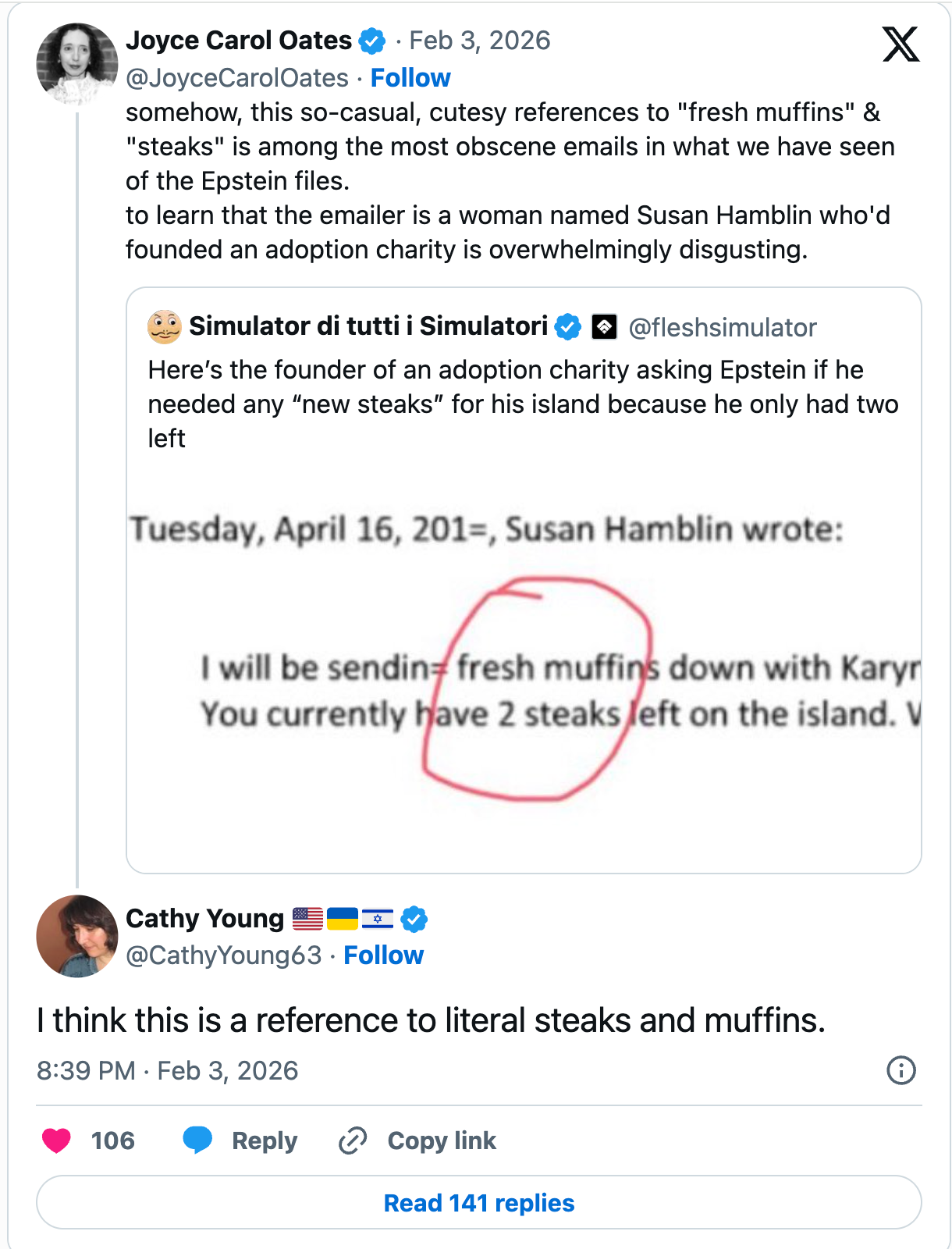

But the longevity of the Epstein story owes less to new facts of criminal conduct than to its symbolic utility in alleging deviancy. The Epstein myth absorbs paranoid thinking from all angles. In the absence of evidence, evidence is invented. The latest document dump provides a case in point, with even highly intelligent people reading symbolic meaning into the most trivial and mundane material:

But as Stanley Cohen observed in Folk Devils and Moral Panics, once a panic gets going it “develops its own internal logic and criteria of proof” and becomes a self-fulfilling system. Doubt is absorbed into the narrative as evidence of a cover-up. Scepticism is perceived as guilt.

Into this self-sustaining system I stepped this week when I wrote on X: “Am I the only person who finds the Epstein story incredibly boring?” I was not denying Epstein’s crimes, defending him, or minimising harm to his victims. I was simply expressing fatigue with a decade-old narrative that continues to produce no new, verifiable evidence of criminality. Within hours, the post attracted a furious backlash, and my account was suspended—almost certainly as the result of a mass-reporting campaign.

My @Quillette boss @clairlemon appears to have gotten her X account suspended because … drum roll …. she said she was getting bored by the endless Epstein-files coverage

— Jonathan Kay (@jonkay) February 3, 2026

I didn’t realize that boredom was a prohibited emotion https://t.co/5z2TMfw9Dw

The suspension was reversed thirteen hours later, but the episode offered new insight into how moral panics function. Those using the Epstein files to perform sanctimony and condemn their enemies reacted not to what I said, but to what I refused to do. I had withdrawn emotional participation in a spectacle and invited others to do the same. But at the height of a moral panic, even something as banal as boredom becomes heresy.

In Bamberg, as in other villages gripped by witch-hunt hysteria in the 17th century, the number of accused grew at an exponential rate. Those charged were tortured until they confessed, and then tortured again until they named accomplices. The logic of the system ensured its own expansion. Each confession justified the next arrest; each arrest produced the next confession. During the largest, most aggressive witch trials, even the architects of the trials were accused and destroyed by the machinery they helped to build.

Epstein mania follows a similar pattern. Despite the absence of evidence leading to further prosecutions beyond Epstein and Maxwell, the story continues to expand through symbolic accusation rather than proof. Pictures of people sitting next to their own children are now being shared as evidence of abuse. Anyone who ever emailed Epstein is now considered an accomplice.

Moral entrepreneurs have repurposed the mythology to indict ever-widening circles of political enemies. The list of suspects grows, not because new facts of criminality emerge, but because a self-sustaining machine requires fresh targets to feed itself. But those who weaponise moral panics to prosecute their enemies are not necessarily spared when the finger of accusation points towards them. Once accusation becomes a virtue, the system can dispense with evidence, limits, and restraint. It only needs new names.