Israel

The Settlers: An Incomplete Portrayal

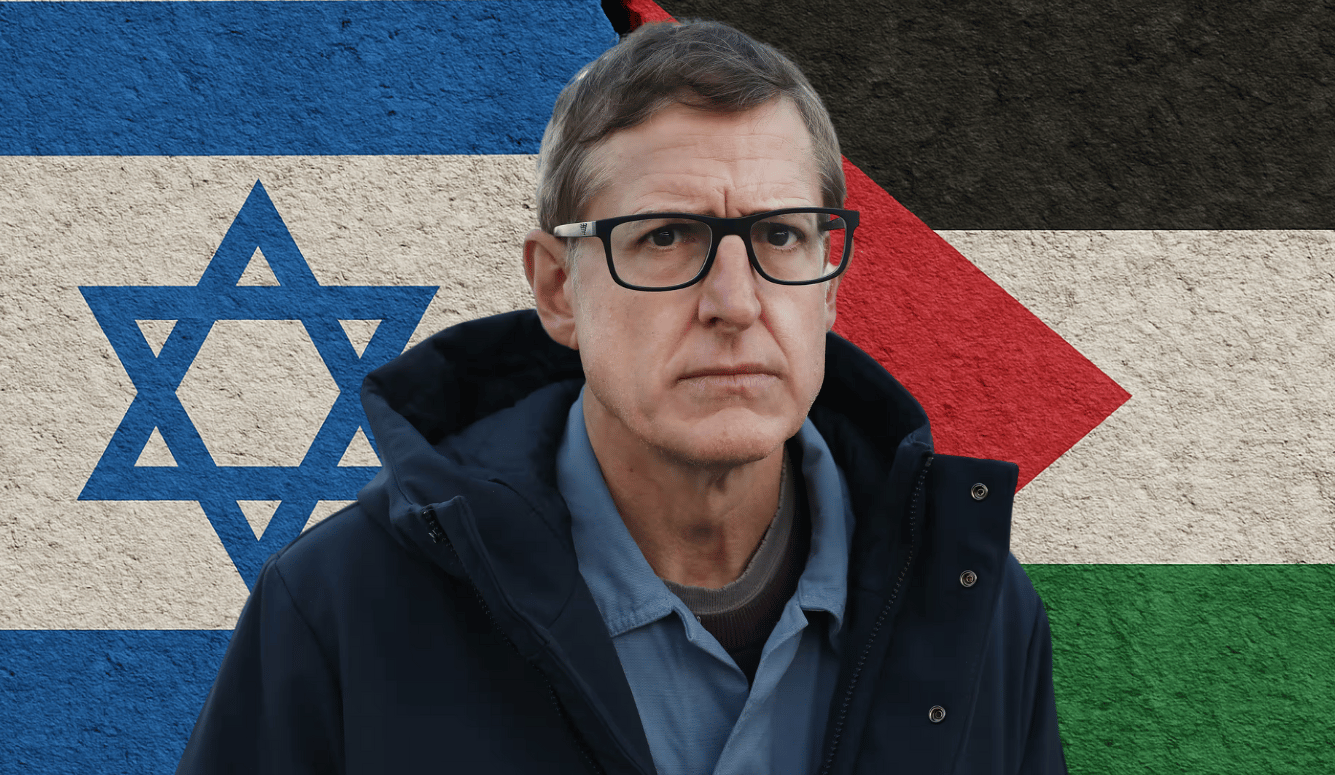

Louis Theroux’s new documentary suggests that he is unfamiliar with the complex history behind the Israeli occupation of The West Bank, and does not understand the political and ideological factors at stake there.

I watched the latest Louis Theroux documentary The Settlers with the same apprehension with which I approach most Western media output relating to the conflict between Palestinians and Israelis. There is nothing quite like the capacity of well-meaning Westerners to grossly misunderstand and miss crucial pieces of the puzzle in regard to the history and context of why Israelis and Palestinians are fighting one another.

While the war between Hamas and Israel has dominated most headlines over the past eighteen months, this particular documentary focuses instead on Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank, and particularly on the growth in Israeli civilian settlements since 1967, when the Jewish state captured the West Bank from Jordan in the Six Day War.

Today, there are over 700,000 Jewish Israelis living there, residing in upwards of 279 settlements, which range from what are effectively modern cities like Maale Adumim and Modi’in Illit, with tens or hundreds of thousands of inhabitants, to ad hoc hilltop encampments made up of tents, sheds, and tin-roofed shacks, housing just a few families.

I’ve had some personal experience of life in the West Bank, because the Palestinian side of my family is from there, and I have visited on multiple occasions, generally staying for months at a time. On my travels, I made excursions into Palestinian cities like Ramallah, Nablus, and Jenin.

Of course, I’ve only seen life from the Palestinian side of the fences. I have never been into an Israeli settlement. Palestinians and Israelis may live in the same land, but we inhabit different worlds, separated not only by fences but by language, religion, and culture—and that is part of the problem. By talking to each other and trying to understand one another, we might be able to build better relationships and forge connections that could transcend the conflict and ultimately end this tragic, horrific, nightmarish fight.

I would appreciate a documentary that gave me a window into a world that I have not been able to see in person and helped me empathise with the people on the other side. Louis Theroux’s documentary did not do that. Instead, it left me frustrated and deflated. Theroux’s settler interviewees were a selection of nasty extremists who lurched between denying the existence of Palestinians and expressing the desire to conquer more land and drive out the Arab inhabitants. Most bizarrely of all, the documentary contains a series of segments with settler leader Daniella Weiss which culminate in her physically assaulting Theroux by pushing and shoving him. Theroux tries to put this in context by interviewing Palestinian activist Issa Amro from Hebron, who explains, “They don’t see us as equal human beings who deserve the same rights as they do.”

I agree that many people dehumanise others in order to justify harming them or going to war against them. This tendency has no doubt played a huge role in perpetuating this conflict. The trouble is that this is a game two can play. There are people on both sides who express disdain for the other group’s rights. Theroux—like many well-meaning Westerners who have intervened in the discussion of this conflict—doesn’t even try to understand the nuances involved, nor does he seem familiar with the complex history behind the occupation. But without understanding this mess, how can we ever hope to fix it?

A major omission in Theroux’s documentary is his failure to mention the fact that, between 1948 and 1967, when the West Bank was part of Jordan, all the Jewish inhabitants were expelled and ethnically cleansed from the land.

“The West Bank” is a relatively new name for this piece of land, a name that was imposed by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan during the years when the area was part of Jordan. The name simply referred to the part of Jordan situated on the west bank of the Jordan river. Its older designation, which many Jews prefer to use, is Judea and Samaria. This land played a major role in Jewish history, and it includes many important Jewish religious sites, including the Cave of the Patriarchs, Joseph’s Tomb, Rachel’s Tomb, and Shiloh. There were at least some Jewish people living on the land for thousands of years, even after the Jews had been enslaved by Rome and expelled from their country and even when they lived in subjugation under various Islamic caliphates.

In other words, this is not just about blind expansionism. The West Bank is of central importance in Jewish history. The act of ethnic cleansing that removed Jews from the area was morally wrong. Ethnic cleansing should never be practised against anyone. By neglecting to mention this, Theroux is ignoring a big part of how and why the settlement movement has taken root and grown.

The bigger and far more practical issues that Theroux skirts around involve the security concerns and broader ideological issues that would have to be factored in before ending the occupation. Let’s say Israel decided to shut down the settlement movement altogether and leave the West Bank. Well, there is a template for that. Under the leadership of Ariel Sharon, Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza in 2005, using the IDF to forcibly evict Israelis who were living there—and we know how that went. Within a couple of years of the Israeli withdrawal, Gaza was taken over by Hamas, who used the land as a base from which to wage a war of total jihad against Israel, ultimately culminating in the 7 October pogrom against Jewish communities in Israel, which sparked the war that is currently ravaging Gaza.

It is important to emphasise that Hamas are not fighting for Palestinian freedom, human rights, or equality. They simply do not believe in such concepts, which they dismiss as alien and Western. They are Quranic fundamentalists fighting an all-out war of religious conquest in the name of Islamic supremacy with the ultimate goal of subjugating, enslaving, expelling or killing the Jewish people.

In fact, if you asked Hamas members or other jihadist ideologues to define an Israeli settler, they would give a totally different definition from the one favoured by most Westerners, as well as by international legal scholars. Hamas consider all Israelis to be settlers because they consider Israel a completely illegitimate entity. When they say that they want the Israeli settlers gone, they mean all Israelis. They see the very existence of Israel as a violation of the Islamic right to rule the land as a Muslim theocracy in perpetuity, a right that they date all the way back to the surrender of the Byzantine empire to the Rashidun army in 636 AD.

In his failure to mention any of this, Theroux creates the impression that the only obstacles to peace are Israeli radicals and settlers. But that’s just simply not the case. Unfortunately, extremist groups play a role on my own side of the conflict as well—something that was brought startlingly home to me when I saw a swastika daubed on a road sign on my most recent visit to the West Bank.

Nothing would be stupider than to allow a war like the one in Gaza to happen in the West Bank. What happened in Gaza after Sharon’s withdrawal should be a cautionary tale. There needs to be an organised and coordinated handover, as well as measures in place to prevent Hamas or a similar jihadist group from taking over either the West Bank or any future Palestinian state. That means that we need a negotiated agreement between the Israeli leadership and a Palestinian leadership that will guarantee mutual security and peaceful coexistence. This is what I have been campaigning for, for many years now, as a means to first de-escalate and eventually end the conflict.

But the reality on the ground is that this remains a distant prospect. Since Palestinians are divided between those who live under the Palestinian Authority and under Israeli military rule in the West Bank, and those who live under Hamas in Gaza, at the moment there is not even a united Palestinian front with which Israel could negotiate. After the war in Gaza, this may change, of course. But the enormous security risks involved in withdrawing from the West Bank will not diminish unless jihadist ideology is totally abandoned. There are many states—including Qatar, the Islamic Republic of Iran, and even Vladimir Putin’s Russia—that would very likely be willing to help groups of Palestinian jihadists continue their struggle to destroy Israel and replace it with an Islamic theocracy. This would probably result in an unimaginably horrific war, just like the one in Gaza today, but on a larger scale. This should be avoided at all costs.

The other manner in which the occupation could be ended would be for Israel to annex the West Bank and Gaza in the same way as they annexed East Jerusalem, which would open up a pathway to Israeli citizenship for Palestinians, and merge Israelis and Palestinians together into a single state. But there is no guarantee that most Palestinians and Israelis would even want this. My understanding is that, generally speaking, Palestinians want to live in a Palestinian state, while Israelis want to live in an Israeli state. Marrying the two would likely risk more violence from extremists unless there were a real reconciliation—which seems an extremely long way away right now.

Most of these considerations are largely absent from Theroux’s documentary. We can talk about the destructive behaviour and expansionist ideology of Israeli settlers all day—but without addressing the other problems inherent to the conflict, this is little more than cheap point-scoring. Yes, we should all condemn the behaviour of violent and lawless settlers in the West Bank, and their crimes, which include burning Palestinian olive groves and attacking Palestinian homes and other properties. But where do we go from there, if the leaders are not willing to make peace with each other? That’s the core problem here. It will take a lot of maturity and hard work to untie this Gordian knot. Crudely blaming everything on one side will not help at all.

Multiple commentators, such as Jake Wallace Simons in The Jewish Chronicle, have suggested that Theroux interview Islamic extremists on the Palestinian side, to enable him to present a more nuanced picture of the challenges that are making it hard to achieve a just and permanent peace. This is a reasonable suggestion, but it seems extremely unlikely to ever happen. Anyone who tried to interview Hamas in the confrontational way in which Theroux interviewed the Israeli settler leaders would be lucky to make it out alive.

Nonetheless, I hereby challenge the leaders of Hamas, including Osama Hamdan, Mousa Abu Marzook, Mohammed Sinwar, and Khaled Mashal to invite either Louis Theroux, a similar Western journalist, or even a Palestinian like myself to interview them in a safe and neutral location and allow us to ask them some hard questions about their ideology, about 7 October, and about their actions in leading Palestinians into the nightmare they are in today.

Could this ever happen? I’m not holding my breath. But meanwhile, documentaries like Theroux’s, which paint a partial picture, are unlikely to get us any further towards a solution that would end the suffering and horror.