Art and Culture

Master of Cinema

Éric Rohmer’s films demand patience and close attention, but they are immensely rewarding for those able to tolerate the absence of spectacle.

I. An Unconventional Entertainer

Was Éric Rohmer a great filmmaker? A lot of people won’t be willing to agree that he was even a good one. In Arthur Penn’s neo-noir Night Moves (1975), Gene Hackman’s private eye spoke for many bemused moviegoers when he dismissed Rohmer’s work as “kinda like watching paint dry.” Rohmer’s defenders will insist that his films are engrossing in their own way, and they are right—but he was certainly not a conventional entertainer.

Rohmer’s films are slow and talky and they usually take ten or fifteen minutes to get into their stride. For the most part, they are so cheaply made that they sometimes feel like the work of an amateur documentarian or an inexperienced art student trying to adapt a short story for the screen. The actors and actresses are generally attractive, but few of them look like movie stars (by American standards anyway). As for the dialogue, it often sounds casual enough to have been recorded by accident.

Nevertheless, Rohmer has turned out to be one of the most influential of all the French filmmakers associated with the French New Wave of the 1950s and ’60s—a list that includes Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Louis Malle, and Claude Chabrol. This is partly due to his pioneering work as a cinema theorist, whose ideas were adopted or absorbed by other filmmakers. But Rohmer also produced the most consistently attractive body of work of any Nouvelle Vague figure.

Rohmer remained an obscure would-be writer-director until his late forties, when he unexpectedly found international success with The Collector (1967) and My Night at Maud’s (1969). These films and a few others—The Marquise of O (1976), Pauline at the Beach (1983), Full Moon in Paris (1984), and The Green Ray (1986)—boast genuine popular appeal, particularly with female audiences, who have always appreciated Rohmer’s keen insight into the emotional lives of young women.

But it is probably a mistake to think of Rohmer in terms of single films. He preferred to work in series of loosely associated narratives, each centred on variations on a particular theme that could be developed film by film over a number of years. Each film in a Rohmer series can be enjoyed as a freestanding work of art, but taken together, each discrete part functions like an individual movement in a symphony or concerto. This is not my analogy: Rohmer said he thought of his work in terms of classical music.

Rohmer’s most accomplished series is a quartet of films collectively titled Tales of the Four Seasons. He wrote, produced, and directed these four films during the 1990s when he was in his seventies, and they have now been re-released together by Criterion in a sparkling new Blu-ray box-set. They have never looked or sounded better, and Criterion’s meticulous restoration confirms that the apparent artlessness of Rohmer’s sound design and visual style was always an illusion. While he frequently made use of improvisation, it was contained within strict limits, and the deliberate pacing, which can be off-putting until you get used to it, was always carefully calibrated. Rohmer’s films demand close attention, but they are immensely rewarding for those able to tolerate the absence of spectacle.

II. Conversational Cinema

Rohmer watched very few films until he was in his early twenties. But while he was living in Paris as a university student, he came to believe that cinema was more vital than any other art form. To teach himself about the medium, he began writing critical essays and reviews, and ended up running a film society that became the de facto meeting place and training ground for the most important figures in French cinema—directors, screenwriters, actors, critics, and even producers all attended his screenings in the late 1940s and early ’50s.

The New Wave directors distrusted films that relied too heavily on novels and stage plays as models, and they cultivated a particular loathing for mindless screen adaptations of literary works. Such films demonstrated disrespect towards cinema as an independent art form (or so they thought). François Truffaut’s celebrated 1954 polemic “A Certain Tendency of French Cinema” forcefully expressed the New Wave’s disdain for the conventions of contemporary middlebrow moviemaking. “Prestige” movies of the 1950s, Truffaut complained, were depressingly predictable because prominent directors and screenwriters had exhausted the possibilities of their approach to storytelling. In response, Rohmer sought to formulate an alternative approach that stripped away all the unnecessary accretions of the “prestige” tradition and started again from zero.

Despite his reverence for silent films, Rohmer believed that sound and dialogue were essential to storytelling. He was particularly inspired by the minimalism of Roberto Rossellini, who followed his “neo-realist” masterwork Rome, Open City (1945) with a new cinema of radical simplicity, beginning with his 1950 biopic The Flowers of Saint Francis. In the 1960s, Rossellini began making didactic historical films for television, the best of which is probably Blaise Pascal (1972). For all their stylisation, these films feel uncannily real with their long unbroken takes and scenes filled with either chatter or extended periods of silence.

Rohmer adopted Rossellini’s method and pioneered what we might call “conversational cinema.” An English-language classic in this genre is Louis Malle’s My Dinner with André (1981), which consists of a single wide-ranging dinner conversation between actor-playwright Wallace Shawn and theatre director André Gregory. Malle was already tangentially associated with the French New Wave, but Rohmer’s influence can be felt far beyond those circles. It is perhaps most evident in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy (1995–2013) and Whit Stillman’s comedies of manners Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), and The Last Days of Disco (1998).

Like Rohmer, Stillman displays an uncommon rapport with his leading ladies, but with an important difference. Stillman’s personality dominates every aspect of his art, so Mira Sorvino, Chloë Sevigny, or Kate Beckinsale could be replaced by (say) Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett, or Kate Winslet without upsetting the balance of his narratives. Rohmer, on the other hand, depended on the personalities of each individual actress to bring his screenplays to life. Love in the Afternoon (1973) could not have been made without the magnetic Zouzou, just as Arielle Dombasle, Françoise Fabian, Béatrice Romand, and Marie Rivière are all essential to the success of Pauline at the Beach (1983), My Night at Maud’s, A Good Marriage (1982), and The Green Ray (1986), respectively. Rohmer’s reliance on good casting is most obvious in The Aviator’s Wife (1981), in which Anne-Laure Meury illuminates the screen as an insolent but guileless teenager. It is hard to imagine the film working nearly as well with anyone else in the role.

Rohmer’s dialogue is not exactly “writerly” in the way that American connoisseurs of cinema often favour. There are few overt literary references, except where they have some direct bearing on the story or the development of themes. His films seem to be talkier than they really are because so many of their conflicts can only be resolved through dialogue. But what is left unsaid is often more interesting and important than what his characters are actually saying. Marie Rivière’s character in The Green Ray is desperately lonely but she is unable to understand or explain why she is so unhappy. The most moving scenes in the film all show her on her own. Nevertheless, critics usually pay so much attention to Rohmer’s dialogue that they neglect his understated talent as a visual artist.

That’s a pity because the images in his films often matter more than the words, and he crafted his visual language with great care and attention to detail. In a fascinating two-part 1994 documentary, Éric Rohmer: preuves à l’appui (“Éric Rohmer: Supporting Evidence”), the wiry, bright-eyed director explains that the design of his films always reflects their thematic and emotional content (part one can be seen here and part two here). The unobtrusive colour coordination is never coincidental, but the palette does not seem stiflingly over-planned, as it does in the films of, say, Wes Anderson or Jacques Tati. As an artist, Rohmer was always thoughtful, but he never let himself be driven by mere thought. He saved his intellect for his critical writing.

III. The Cahiers Years

Antoine de Baecque and Noël Herpe’s 2014 biography of Rohmer is an impressive achievement. In 600-plus pages, the authors describe the uneventful life of a very private man whose work was almost never autobiographical because there was so little about his existence that was worth turning into art. He left behind no memoirs, and his surviving correspondence reveals little of his inner life. One sometimes wonders whether he had something to hide. He certainly behaved as though he did: Éric Rohmer was not even his real name.

Maurice Schérer was born in 1922. When he was thirty, he combined the names of Hollywood pioneer Erich von Stroheim and Sax Rohmer (creator of the legendary supervillain Fu Manchu) into his pseudonym. Anonymity was necessary because his overbearing mother would not have approved had she discovered that he had anything to do with the cinema. She died in 1971, aged 84, without ever learning that her elder son had become a world-famous writer-director.

Rohmer’s family was bourgeois, but his forebears on both sides had been peasants within living memory. This explains his mother’s obsession with her sons’ social status—in her eyes, Rohmer was merely an unsuccessful would-be academic, who failed the entrance exams for the École normale supérieure three times, and was forced to settle for a life as a Classics teacher in Paris. His younger brother, on the other hand, became a university professor, although he also had to hide his passions from his mother: after her death, he became a well-known gay-rights activist.

Rohmer remained a bachelor until the age of 37. After that, he lived with his wife and two sons in genteel poverty until he was almost fifty. After the success of My Night at Maud’s, the couple was finally able to afford a flat with its own bathroom. His long apprenticeship helps to explain the simplicity of his work: by the time he started making films, his main literary and philosophical influences had already been absorbed and become a part of him.

The years Rohmer spent drilling French teenagers in ancient literature, Latin grammar, and Classical Greek syntax provided him with an unparalleled view of young people’s emotional development and intellectual growth. This decade and a half of demanding work also helped make him an unpretentious and accessible communicator (at least with his chosen audiences). Of course, another explanation for the simplicity of Rohmer’s work might simply be that a series of humiliations had taught him not to show off his learning or anything else.

In his twenties, Rohmer published a novel and some short stories. None of these works succeeded, although they did contain ideas that, decades later, he would develop into some of his finest screenplays. He first made his name as a film critic, convinced that the cinema was the preeminent postwar art form. He struck up a friendship with André Bazin, who died aged forty in 1958 but still managed to help transform film criticism from a kind of light journalism into a serious philosophical endeavour.

Dudley Andrew, professor emeritus of film studies and comparative literature at Yale, has devoted much of his career to studying Bazin’s life and work. His 1978 biography is essential, as are his translations of Bazin’s critical essays, the most recent collection of which was published in 2022. These reward careful study, not least because Bazin was one of the central figures in postwar intellectual life, at least in France. His ideas remain in wide circulation today, even if most film students and filmmakers can’t remember where they originated.

In 1951, Bazin co-founded the Cahiers du cinéma, which became the most influential movie magazine in the world for a dozen years or so, and retains a certain prestige even today, thanks to its role in nurturing and publicising the ideas of François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol and—of course—Rohmer himself, who edited the journal between 1957 and 1963.

Bazin, Chabrol, and Rohmer were the most intellectually disciplined of the critics who wrote for the Cahiers. Much of their writing holds up today whereas once-explosive essays by Truffaut, Godard, and Jacques Rivette now seem quaint and dated, or else difficult to read because they are filled with references to films, books, and other cultural artefacts that have since been forgotten. Rohmer was to film criticism what T.S. Eliot was to literary criticism: a practitioner who knew how to talk shop about his work.

Rohmer edited the Cahiers with great sensitivity and intellectual generosity. Perhaps with too much intellectual generosity—his more radical friends in the New Wave became frustrated by his careful avoidance of political tribalism, and he was ultimately ousted by Jacques Rivette, who sought to politicise the journal and bring it into line with his rigid notions of Marxist orthodoxy. Rivette was a talented filmmaker in his own right (albeit one who never really had audience pleasure in mind) and he wasn’t personally hostile to Rohmer. But he was a narrow-minded and intellectually second-rate Cahiers editor, who lasted less than two years in the job before handing over control to younger, even more passionate radicals.

The journal rapidly degenerated into incoherent Maoism—a period that lasted roughly from 1968 to 1973—before recovering some sense of balance and settling into its current irrelevance as an academic-sounding publication that only its contributors bother to read. In April 1970, it published an interview with Rohmer that was reposted on the Senses of Cinema website in English in April 2010. The four Cahiers interviewers began by telling their readers, “Everything in this interview with Eric Rohmer opposes us to him,” and the interrogation that followed was so hostile to Rohmer’s point of view that they accidentally provoked him into revealing what he really thought:

ROHMER: Seeing as you are pushing me there, I will go further. Not only is there beauty and order in the world, but beauty and order are only in the world. For how could art, a human product, be the equal of nature, a divine work? At best, it is only the revelation, in the universe, of the hand of the Creator. I’ll admit: there is no position more teleological, more theological, than my own. This is the position of the spectator. If he hadn’t already found beauty in the world, how could he pursue it in images of the world? How could he admire the imitation of life, if he didn’t admire life itself. This is the position of the filmmaker. If I film a thing, it’s because I find it beautiful; therefore, it’s because it exists in the nature of beautiful things. This is the position of every artist, of every appreciator of art. If I didn’t find nature beautiful—light, air, the sky, space—I would not find any painter beautiful, neither Leonardo, nor Turner, nor Hartung.

To which he adds this irritable coda: “But enough with generalities. Could you not pose me some more precise questions?” More than once he loses patience with the philosophical line of inquiry:

Listen, I’m not looking for explanations, I’m giving you a fact. Maybe some of my colleagues don’t find it important to work on pre-existing things. But I belong to the group of those who need to work on living material and not within abstraction. That’s all that I can say on the matter.

Readers should be grateful to the interviewers for their bad manners, because they elicited some of Rohmer’s most candid remarks about the nature of his art:

I think that the goal of the cinema is to come as close as possible to reality and that one can perfectly well envisage a history of the cinema where one showed that the cinema has not stopped discovering nature and going towards the natural. It hasn’t entirely got there, there are plenty of things that still can’t be shown by the cinema, but we will get there. ... I have no fear of being close to real life. I seek to eliminate whatever still distances me from it, even if I know that I will never get there entirely. I know that there will always be an outer limit. I don’t seek to work at this outer limit, to make it evident, although I think it’s possible that in wanting to go further, I will arrive at what you call abstraction. ... To believe that the cinema has gone far enough in terms of realism and that it should turn its back on it seems to me to be very sterile, even dangerous. What interests me are the investigative powers that the cinema can have.

Until the end of his life, Rohmer regarded this encounter as a Maoist struggle-session. Decades later, in one of his very last interviews, he was evidently still bitter about the experience. He didn’t enjoy being forced to reveal what he really believed.

IV. My Night at Maud’s (1969)

In the 1950s, Rohmer began experimenting with 16mm film, which he preferred to the 35mm format used in almost all commercial cinema. The lightweight cameras allowed for greater freedom and he liked the grainy and slightly softer image produced by blowing 16mm film up to 35mm for projection, especially in colour.

He may also have resisted 35mm because his first attempts to make a full-length feature film in the 1950s were both expensive failures. The first was never even released and has since been lost; the second, The Sign of Leo, was released in 1962—three years after it was made—and failed at the box office. For a while, Rohmer seemed to be the New Wave’s resident loser—better at talking or writing about films than actually making them.

After being forced out of the Cahiers, Rohmer got a job making documentaries for French educational TV. This experience taught him how to make films cheaply, quickly, and efficiently. It also provided him with the material he would draw upon throughout his career as a filmmaker. The most famous of the documentaries he made during this time was released in 1965. It features a twenty-minute conversation between a Dominican friar and a communist philosopher about the 17th-century philosopher, mathematician, and Christian mystic Blaise Pascal.

Rohmer was a practising Catholic, but he found it fascinating that the communist seemed to understand Pascal and Catholicism much better than the friar, whose progressive theology seemed to railroad him into incoherence, hypocrisy, and doublethink. Their polite debate planted the seed of an idea that Rohmer would develop into the sex comedy My Night at Maud’s, released in the summer of 1969. It is still Rohmer’s most financially successful film and many critics insist that it’s his greatest work.

My Night at Maud’s has always been controversial among Catholic intellectuals—not on account of any blasphemy or unorthodoxy, but because it seems implicitly to embrace a sternly reactionary form of traditionalist Catholicism. The unnamed protagonist (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is a parody of the trendy modern Catholic intellectual. His life is a lie because he doesn’t really believe in the Church’s teachings or try to live by them. In fact, he doesn’t have much of a spiritual life at all. His faith simply provides him with excuses for his own hypocrisy and cowardice.

The film is a snapshot of an unusual moment in French history. The Vatican’s reforms of the 1960s had not yet succeeded in driving people away from the Church, but the signs of imminent collapse were already apparent. Rohmer shows just how dull the Catholic Mass became once the ritual was changed and the priests were prevented from celebrating it in Latin, and how half-hearted the congregants were as a result. Instead of praying during the Mass or paying attention to the priest, Trintignant looks around for pretty girls.

Trintignant’s character is a solitary, weak-willed engineer who recently converted back to Catholicism. He behaves like an “intellectual,” but it is not clear if he is actually that intelligent or just socially awkward. Nor is it clear if his Catholicism is genuine, or if it is just a convenient identity that makes him seem more interesting, and helps him rationalise his eccentricities (not to mention his weakness and cruelty)? The only other Catholic we meet is Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), a petite, pretty churchgoing blonde who turns out to be even less admirable. She also uses Catholicism as a substitute for a personality, but it does nothing to make her a better person.

Early in the film, our hero runs into his old friend Vidal (Antoine Vitez), a communist libertine who teaches philosophy at a college. And like the communist in Rohmer’s documentary, Vidal seems to understand Pascal far better than his Catholic friend. They call on Vidal’s not-quite-lover Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced paediatrician with an eight-year-old daughter. Maud seems to be irresistible but Trintignant shows no interest in her, even though she is clearly interested in him.

Maud comes from a family of freemasons and atheists and Vidal is a communist, yet both of them seem to be more virtuous and honourable than the film’s Catholics. Maud really wants him to be a true believer instead of the manipulative weakling he is. My Night at Maud’s can be enjoyed purely as a sex comedy (albeit an austere and cerebral one), except that it is too touched with melancholy to be a farce. And as in so many of Rohmer’s films, the most appealing characters are the ones who end up suffering the most.

My Night at Maud’s was part of Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales series. In the 1970s, he moved in an experimental direction with The Marquise of O and Perceval le Gallois (1978), which are far more daring and original than any of Jean-Luc Godard’s attempts to impose Bertolt Brecht’s ideas on cinema. Then, in the 1980s, Rohmer produced his sunniest and most accessible films in his Comedies and Proverbs series. It seems incredible that a man in his sixties could have had such insight into contemporary youth culture. But Rohmer treated his cast members as collaborators and encouraged them to bring their own lives into their work, which is how he managed to keep up with Parisian youth culture far better than his more self-consciously fashionable contemporaries.

At some point in the 1980s (it isn’t clear exactly when), Rohmer watched Jonathan Miller’s 1981 BBC production of Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale. Although Rohmer could not speak or read English especially well, he adored Shakespeare, particularly when presented in a traditional manner by classically trained actors. A Winter’s Tale is one of the last plays Shakespeare wrote, along with The Tempest and Cymbeline. These late plays have the feeling of a farewell to the theatre, and Rohmer was inevitably reminded of his own mortality. So, he began to contemplate what his own last works might look like. The result was his crowning artistic achievement.

V. The Four Seasons Tetralogy

Rohmer released the first of his Tales of the Four Seasons in 1990. A Tale of Springtime is the least satisfying instalment in the quartet, not because it’s a bad film but because the others are so good. In this film, Rohmer began experimenting with ways to incorporate resonant mythical archetypes into apparently trite contemporary situations. A Tale of Springtime is the story of a friendship between nineteen-year-old music student Natacha (Florence Darel) and Jeanne (Anne Teyssèdre), a philosophy teacher at an inner-city school. It soon becomes clear that Natacha is looking for a mother-figure, not a friend.

The plot is, as always, deceptively slender. At a party, Jeanne meets Natacha, who has her family’s large flat all to herself: her mother lives in another city and her father Igor (Hugues Quester) spends most of his time with his snarky young girlfriend Ève (Éloïse Bennett). Natacha cannot stand Ève and thinks her father would be happier with Jeanne. So, she invites Jeanne to spend the weekend, and begins to draw her into the family circle. Unfortunately, her matchmaking plan does not work out as smoothly as hoped.

Perhaps the most interesting scene involves a tense dinner-table discussion about philosophy. Ève repeatedly baits and provokes Natacha, drawing attention to her weak grasp of intellectual issues, while Jeanne tries to mediate between the two adversaries and Igor watches haplessly. Metaphysics is a natural, perhaps inevitable topic of conversation between a philosophy professor, a philosophy postgrad, and Natacha, who got excellent marks in philosophy at school but doesn’t know the subject very well. Despite his background as a Classics teacher, Rohmer wasn’t a pedant and he displays no interest in the intellectual preening that marred much of Godard’s work. He was interested in the social dynamics, not the merits of a particular political argument.

The second instalment of the seasons series, A Tale of Winter, was released two years later, and some critics maintain it is Rohmer’s finest film. That claim is debatable but the film’s brilliance is not—particularly its authentically Shakespearean atmosphere. You don’t need to be familiar with A Winter’s Tale to enjoy the film (after all, Rohmer only knew the play from a TV adaptation). During the late 1980s, Rohmer appears to have had a crisis of faith, and A Tale of Winter seems to be part of his attempt to think his way back into belief in God, the immortality of the soul, the resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the reality of miracles. Without those beliefs, Christianity amounts to nothing more than a series of rituals, symbols, and arbitrary rules held together by myth. And how do you find meaning in something that you don’t think is true? So, this film was not just an intellectual exercise, it was a personal exploration.

As usual, Rohmer doesn’t create a devout Catholic as a stand-in for himself. He investigates the intellectual conflicts in modern Christianity through the eyes of an unimpressive would-be intellectual named Loïc (Hervé Furic), a kind but pedantic librarian who still identifies as a Catholic, even though he doesn’t believe in miracles or attend Mass. He prefers to pontificate about philosophy instead but manages to be even less impressive on this score than Jean-Louis Trintignant’s character in My Night at Maud’s.

The story’s protagonist is Félicie (Charlotte Véry), a hairdresser who has lost the love of her life but remains stubbornly optimistic. We learn that she is “spiritual but not religious,” and that she believes in true love, the immortality of the soul, and the existence of a “soulmate.” Unlike her mother, she is reluctant to get involved with organised religion, but she believes in miracles, the power of prayer, and the sanctity of human life. The film opens with warm scenes of a seaside holiday, where Félicie enjoys a brief but intense romance with Charles (Frédéric van den Driessche), a handsome chef who is just about to leave for America. At the end of the holiday, they exchange details, but Félicie accidentally gives him the wrong address and never has a chance to tell him that she is pregnant.

Most of the film unfolds during the Christmas season five years later, in the dreary suburbs of Paris and the picturesque cathedral town of Nevers. Félicie now lives with her four-year-old daughter and her wise, gentle mother, but she has never forgotten Charles. She thinks of him all the time and never stops talking about him with either of her current boyfriends—her white knight Loïc or her boss Maxence (Michel Voletti), who wants her to move to Nevers with him. She agrees without realising that Maxence really just wants her to be an employee in the hair salon he plans to open and an occasional bedmate. Her situation remains unstable because she refuses to give up hope that she will see Charles again and live happily ever after.

A Tale of Winter is an unpredictable and highly original exploration of the supernatural. Rohmer deliberately avoids ventriloquising Catholic orthodoxy on questions of whether (for example) authentic miracles really take place. Instead, he allows Félicie and a practising Wiccan to win a polite after-dinner argument with Loïc about reincarnation. Again, it turns out that Félicie understands Pascal’s philosophy and the nature of Christianity better than the film’s self-appointed Catholic intellectual does.

Rohmer’s mastery of tone here is exceptional. After the sunny opening scenes at the seaside, the film often looks so cold and bleak that it is a relief to see the cosiness of Félicie’s mother’s house, the warm light of the nativity scene in a church, and the sparkle of Christmas decorations in town centres. Otherwise, the colour palette is generally depressing. In this respect, A Tale of Winter has much in common with Rohmer’s 1984 feature Full Moon in Paris, in which the main character also finds herself caught between three men—an effete simp, a large (and somewhat threatening) boyfriend, and the handsome man she really wants to be with. But while the earlier film is almost a tragedy, this one is a romance that Rohmer pulls off with sensitivity but without sentimentality.

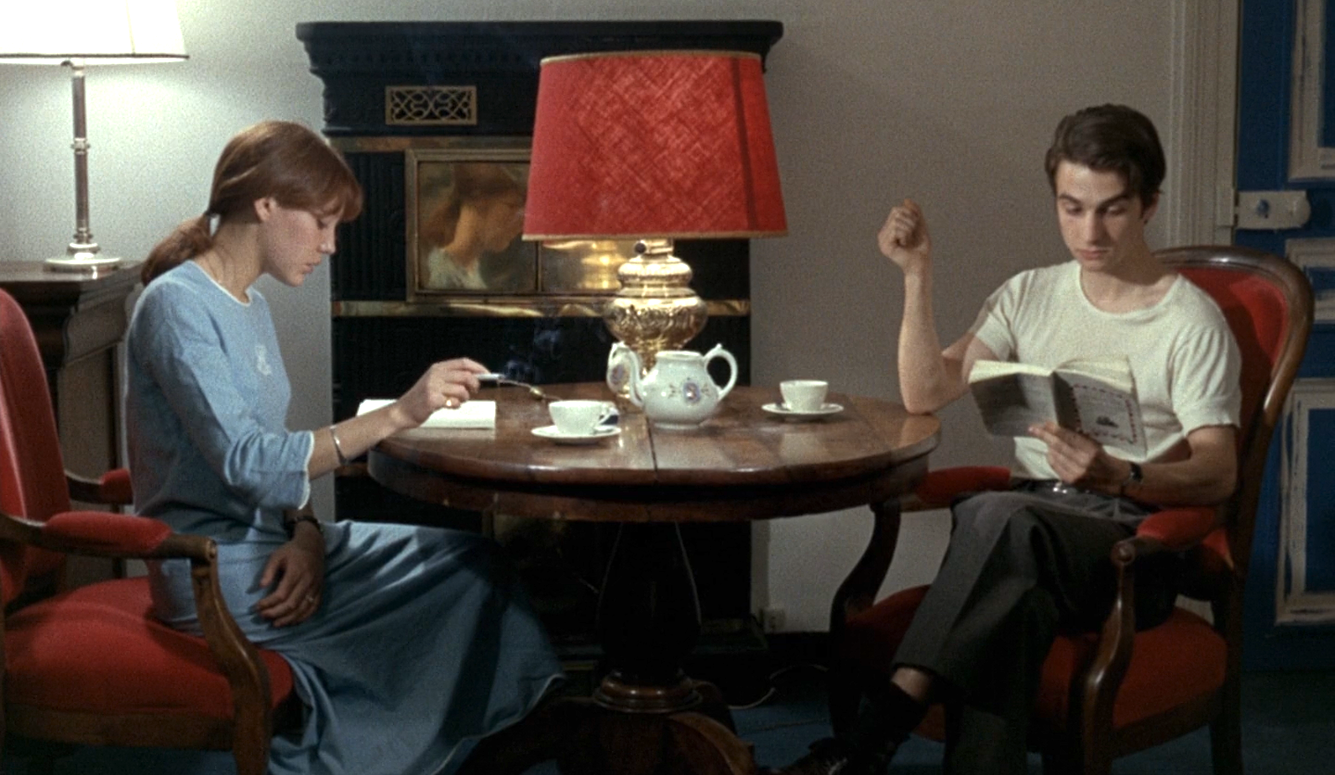

The situation of Full Moon in Paris and A Tale of Winter is reversed in A Summer’s Tale (1996), in which the hero (if that’s the word for such a man), Gaspard (played by Melvil Poupaud), finds himself caught between three women, each of whom embodies a personality type (and type of beauty) that recurs throughout Rohmer’s work. There is Margot (Amanda Langlet), a cheerful short-haired brunette who befriends him on the beach; Léna (Aurelia Nolin), a beautiful but sometimes icy blonde who is his moody on-again-off-again girlfriend; and Solène (Gwenaëlle Simon), a sensualist with long dark hair who wants to seduce him.

According to Rohmer, A Summer’s Tale was his most autobiographical film. But if Gaspard is a self-portrait, it is not a flattering one. Indeed, he is one of Rohmer’s most unattractive male characters: as one character points out, it is hard to tell whether he is cunningly manipulative or a weak fool. “I don’t like to push my luck, I like my luck to push me,” he says. He is a mathematics student on holiday in Brittany with only his guitar to keep him company as he waits for his girlfriend to join him. His solitude is broken by Margot, who is so charming and outgoing that it is not immediately clear what she could possibly see in Gaspard. She rebuffs his clumsy advances at first, but invites him for a night out at a disco with her friends. He is uncomfortable and out of place there but somehow attracts the attention of Solène, to whom he seems to be the romantically temperamental musician of her dreams. But just as their romance begins to blossom, Léna shows up.

Folk music and traditional sea shanties play an unusually important role in this film. Sometimes it feels like a music documentary or a history of Breton culture. Margot, Gaspard, and Solène are all musical, and they are fascinated by the local traditions they encounter among the fishermen around them. Gaspard even decides to compose a shanty of his own. There is no sense that these young people spend their evenings letting American mass media wash over them; this is perhaps the one element in the film that 21st-century audiences might find hard to believe. But the actors were actually interested in these things in real life, and one of Rohmer’s principles as a filmmaker was always to let the cast develop their characters in line with their own personalities.

It is easy to forget that A Summer’s Tale is a fictional narrative. This illusion of reality is especially pronounced during scenes when characters take walks along the beach together and Rohmer captures their drifting conversations in impossibly long takes. The sound design is ingenious: other directors are content to represent the seaside with the sound of seagulls and crashing waves, whereas Rohmer creates the illusion of an entire world outside that his characters don’t even notice.

The final film in this quartet, Autumn Tale (1998), feels just like one of Shakespeare’s comedies. Rohmer obviously couldn’t reproduce Shakespeare’s dense verbal textures, but he managed to recreate an authentically Shakespearean tone, with a piercing bittersweetness beneath the levity of the plot. The effect is entrancing, and this is surely Rohmer’s warmest, richest, and most satisfying accomplishment. There is even an admirable male character for once. Rohmer was 78 years old when this film was released, and it feels like a final statement. Even though he followed it with another three films (including The Lady and the Duke, which is perhaps the best film ever made about the French Revolution), Autumn Tale is the last film for which he wrote an original screenplay.

Autumn Tale stars two actresses who owed their careers to Rohmer. Béatrice Romand first appeared in Claire’s Knee (Rohmer’s 1970 follow-up to My Night at Maud’s) and later played the cheeky but unwise lead in A Good Marriage. Marie Rivière was given small roles in Perceval and The Aviator’s Wife, but finally had her breakthrough in 1986 at the age of thirty when she starred as the lonely, depressed, and fragile Delphine in The Green Ray. Romand also had a small but memorable role in that film as one of Delphine’s catty friends. The two women enjoy a much warmer relationship in Autumn Tale, although the tables are turned: this time Romand is the lonely one and Rivière is the unhelpfully helpful friend.

Romand stars as Magali, a widowed winemaker in the Rhône Valley whose best friend and neighbour Isabelle worries that she is throwing herself into her work to distract herself from her desperate loneliness. As Isabelle, Rivière is unusually chic for a woman who sells books in a provincial town. Magali, on the other hand, has frizzy hair and tired eyes. She is still attractive, but she no longer bothers to take care of her appearance. Isabelle decides to help her find a man, and places a personal advert in a newspaper on Magali’s behalf without telling her.

But Isabelle is not the only self-appointed matchmaker in this story. Magali is also close to her son’s girlfriend Rosine (Alexia Portal), who spends a lot of time fending off the attentions of her old flame and former philosophy professor Étienne (Didier Sandre). She wants to set him up with Magali, who is closer to his own age—and thus too old for his tastes. Meanwhile, Isabelle tries to match Magali with Gérald (Alain Libolt), a handsome widower. Unfortunately, he is strongly attracted to Isabelle...

Much hilarity, as they say, ensues amid the landscapes and pretty towns of Provence, which is depicted without the usual pastoral clichés. As always, Rohmer is content to show, not tell.

VI. A Late Bloomer and Authentic Master

The best way to enjoy Rohmer’s films is on the big screen, preferably early in the evening so you can chat about them afterwards over dinner until it’s time for bed. But the Criterion Collection’s new Blu-ray box-set of Tales of the Four Seasons is the next best thing. Each film has been cleaned up and remastered so that it looks and sounds just as Rohmer originally intended. Audiences without French will be grateful for the sensitively translated subtitles.

There is no need to sit through all of Rohmer’s previous work to derive great pleasure from these ones. That said, it is most rewarding to experience his work in sequence, at a rate of no more than one film a week at most, so you have a chance to observe how he blossoms as an artist over time. He was a late bloomer, like his compatriot and fellow-classicist Nicolas Poussin, the 17th-century painter who seems to have influenced the Tales of Four Seasons with his own last major works, the Four Seasons cycle of paintings, all of which are in the Louvre.

Rohmer and Poussin were kindred spirits. Poussin produced no good work before the age of thirty, no great work before the age of 35, and nothing that demonstrates a virtuoso talent. Art did not come easily to him; his career was a triumph of sheer willpower. But what he lacked in natural skill, he made up for with intelligence, discipline, patience, and self-mastery. He painted his Four Seasons in old age when arthritis made it painful to hold a brush, and a persistent tremor made it even harder to control what he painted. For all that, like Rohmer, his final series crowned his career.

Not all audiences will be able to stomach Rohmer’s leisurely pacing. But those who are not in a hurry should now be able to agree that he was an authentic master of cinema.