Australia

The Original Aboriginals

Australia is one of the only places where humans maintained a hunter-gatherer lifestyle into the modern era. This makes it an invaluable window into humanity’s deep past—a window that is closing.

Australia was the last continent to experience the Agricultural Revolution. Since humans have been hunter-gatherers for most of our existence, there is immense value in studying the peoples who inhabited pre-agricultural Australia. But there is a frustrating lack of consensus over what we should call them, and how to distinguish them from the current inhabitants of Australia.

One common term for them is Aboriginal Australians. However the current legal and scientific definition of “Aboriginal Australian” lacks any externally-verifiable criteria. The word “Aboriginal” comes from Aborigines, the Latin name of a primitive tribe that once lived in Italy. It’s possible that the root of this word was ab origine, “from the beginning.” When the British began colonising other lands, they used “aborigine” and “aboriginal” to refer to the people they came across. For specific groups, such as the inhabitants of Canada and Australia, they used the proper noun “Aboriginal” and the proper adjective “Aboriginal.”

Over time, the definition of “Aboriginal Australian” has become increasingly ambiguous. Aboriginal identity is now based on self-identification, rather than lifestyle, language, ancestry, genetics, or appearance. Most Aboriginal Australians have little in common with their pre-colonial ancestors, and there is no way to tell if someone is Aboriginal except by asking them. Simultaneously, Aboriginal individuals and corporations are being given increasing amounts of control over all remains, artefacts, and resources associated with pre-colonial Australia.

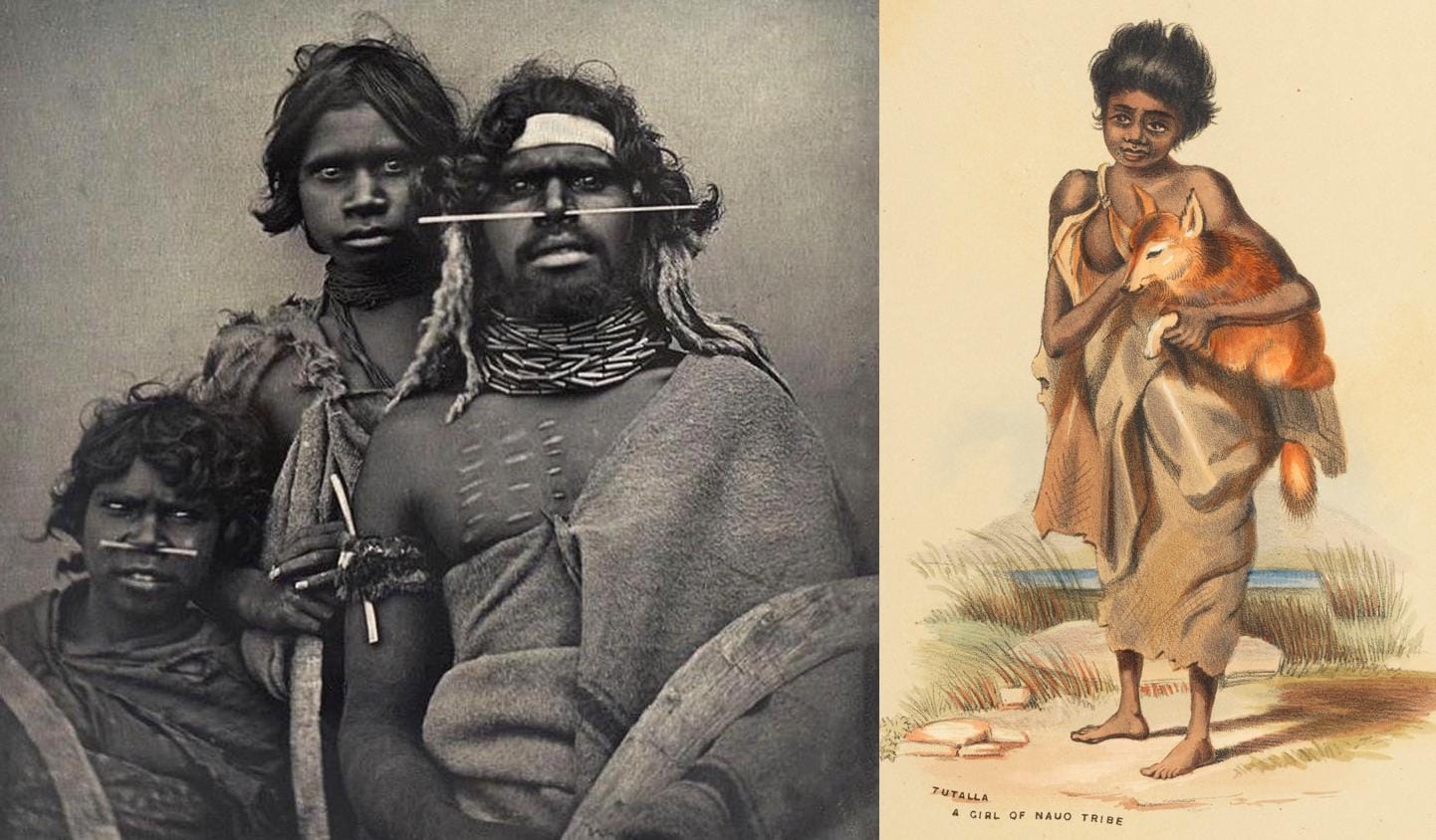

Everyone in this photo is an Aboriginal Australian pic.twitter.com/NO5X6CnKLa

— Mungo Manic (@MungoManic) January 25, 2025

To understand—and preserve—Australia's past, we need more precise terminology. Every person living in Australia today, regardless of their ancestry or identity, participates in an agricultural food system—they are all “farmers” in a sense. In contrast, all pre-colonial inhabitants of Australia were “foragers,” obtaining their food exclusively through hunting, fishing, and gathering. To highlight this dietary and economic divide, I will refer to the latter as “Australian foragers.”

When the British first landed in Australia, the foragers they encountered belonged to hundreds of different language groups, each consisting of politically independent bands. These people had simple material technology but sophisticated kinship systems and laws, which varied greatly by region.

None of them engaged in farming, animal domestication, or pottery-making. They modified their environment through activities like bushburning, building stone fish traps, and creating shell middens. Bands were semi-nomadic and foraged within traditional territories. Most built temporary shelters, although some cultures were more sedentary and constructed larger, more permanent structures.

Physical traits such as height, hair type and texture varied by region. While most had black hair, childhood blondism was present in the central deserts and hair texture ranged from nearly straight to curly. There were reports of individuals over 7 feet tall (213 cm) along the Kimberley coast, while many people in the Cape York rainforest had pygmy-like stature. Some physical variations seemed to follow environmental patterns. People in the tropical north had darker skin while those in the southeast were paler and became sunburned in the spring when they stopped wearing their possum-skin rugs. On the isolated island of Tasmania, the foragers were physically distinct from mainland populations in several ways. Their skulls were rounder and their hair was more tightly curled.

Economically speaking, their social organisation was remarkably egalitarian. Most groups lacked formal hierarchies, and none had developed inequalities of wealth. Leadership typically rested with elders, particularly men who held sacred knowledge, rather than political chiefs.

There were various methods for handling disputes: one-on-one duels; regulated group battles with clear rules of engagement and, most of the time, few casualties; formal punishments, such as executions and spear-dodging; and brutal massacres to avenge severe grievances.

Inter-group conflicts had two main causes: disputes over women and revenge for wrongs, including suspected sorcery. Notably, Australian foragers rarely fought over resources or territory, in stark contrast to many agricultural societies. When violence did occur, its intensity often correlated with social distance: most often, conflicts between related groups followed stricter rules to limit casualties, while fights with strangers were more deadly.

Australian foragers never adopted bow-and-arrow technology, relying instead on spears, spear-throwers, clubs, and non-returning boomerangs. The most lethal weapons were reserved for human conflict rather than hunting. Cultural variations existed—for instance, the didgeridoo was only present in northern regions such as Arnhem Land, an area where boomerangs were not used for hunting or fighting. The spear-thrower was not ubiquitous either, and in some regions spears were simply thrown by hand. Technological change was slow. Much of the forager lifestyle would have been familiar to their Pleistocene ancestors. But everything changed with the arrival of European agriculturists.

It’s unknown how many people lived in pre-colonial Australia and Tasmania. Estimates range from 300,000 to over a million. Evidence suggests that the population began to decline around 400 years ago, possibly with the introduction of diseases carried by Indonesian trepang hunters. Beginning in 1788, foragers and farmers coexisted in Australia for nearly two hundred years. Relationships between the two groups varied. Some forager bands traded with the newcomers, some fought them, others did both. Many foragers initially thought the Europeans were dead relatives who had come back to life. This belief stemmed from the mortuary practice of removing the skin’s melanin-containing outer layer which revealed an under-layer that was pale, like European skin. The newcomers clashed with the older inhabitants over hunting rights, encroachment on territory, abductions, especially of forager women, and similar offences. It’s unknown how many foragers were killed by the newcomers, but at least 10,657. By far, the worst enemy of the Australian foragers was European and Asian diseases, against which their otherwise impressive immune systems had no defences.

The population dropped sharply. In Tasmania, the decline was fast and mostly complete. One of the last Tasmanian foragers, Truganini, died in 1876, just a hundred years after Captain Cook first encountered her people. Only a few Tasmanian women who married European migrants still have living descendants. In Australia, many bands and language groups in the southeast also went extinct, though northern and central regions were somewhat less affected. By 1933, there were only 36,000 remaining Australian foragers left, together with 44,000 former foragers or descendants of foragers. The last band of foragers, the Pintupi Nine, entered modern agricultural society upon contact in 1984. This marked the end of humanity's longest continuous foraging tradition.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Australian government practised a policy of assimilation designed to culturally and racially absorb the descendants of Australian foragers. This led to the forced removal and education of many children who were descended from both foragers and Europeans.

After this policy was abandoned in the 1960s, terms like “half-caste”—designed to calibrate the extent of someone’s genetic heritage—fell out of favour as people shifted to a binary understanding, in which one is either Aboriginal or not. Now, even geneticists who study Australian-specific DNA agree that Aboriginal is a culturally-based affiliation and cannot be defined genetically.

Nominally, the government uses a three-part test for discerning whether someone is Aboriginal: the person must identify as Aboriginal; the Aboriginal community must recognise the person as Aboriginal; the person is Aboriginal by descent. But since there is no clear definition of what constitutes the Aboriginal community or Aboriginal descent, this is circular logic that makes external verification impossible, which is why scientists and government entities, such as the Australian Bureau of Statistics only use the first part: self-identification.

In 2021, 812,000 Australians identified as Aboriginal—a fivefold increase from 150,000 in 1981. This is largely due to the fact that being Aboriginal has become less stigmatised and genetic criteria are no longer used to determine Aboriginal identity, neither are there any genetic criteria for identifying as Indigenous, First Nations, or Blak. A few descendants of Australian foragers even identify as white.

Some Aboriginal Australians, especially in rural areas, are genetically and phenotypically similar to Australian foragers, speak their languages and observe many of their laws. Other Aboriginal Australians have pale skin and blue eyes, little or no forager DNA, and do not speak pre-colonial languages or follow pre-colonial laws and customs. And of course many fall somewhere in between.

As it stands, Aboriginal identity is a social construct. In many ways, it parallels the idea of European royalty. Both groups are often heavily invested in their family trees, use traditional regalia, feel an emotional connection to cultural myths, exert an influence over historical narratives, are recognised by governments, exercise moral authority, control land and artefacts, and lead official ceremonies. Both groups resist outsider attempts to claim membership or question their legitimacy.

In some contexts, there may be no harm in equating Aboriginal Australians with Australian foragers or allowing anyone to identify as Aboriginal, but the use of this poorly-defined term in legal and scientific contexts can have disastrous effects. One example is the treatment of ancient remains. Aboriginal corporations, aided by the Australian government, have been actively removing Australian forager remains and artefacts from institutions worldwide. These items are then placed in private collections or buried in undisclosed locations, regardless of their age or scientific significance.

Some of these cases involve reclaiming the bodies of recently deceased people that were stolen by grave robbers and are now being reburied by their direct descendants. But such clear-cut cases are in the minority. More typical is the case of Mungo Man. This 40,000-year-old fossilised skeleton, discovered on the shores of now-dry Lake Mungo, was one of the world’s most significant archaeological finds. In 2001, scientists claimed to have extracted DNA that showed that Mungo Man was not ancestral to any known human population. A subsequent study failed to replicate these findings. Nevertheless, the possibility that recent Australian foragers were not descended from Mungo Man’s people caused controversy. Some scientists and local Aboriginal leaders advocated for the fossils’ preservation and continued study, but the Australian government ultimately sided with the AAG, an Aboriginal corporation seeking reburial. In 2022, Mungo Man was secretly buried in an undisclosed location.

Over the past fifty years, Australian paleoanthropology has taken one step forward and ten steps back. Only a handful of DNA tests were ever conducted on Australian human fossils before their removal from museums and universities. All that remain are measurements and increasingly rare photographs. New fossils found at Lake Mungo and other such sites are usually ignored and are quickly eroded and destroyed by the elements. This loss of archaeological evidence creates irreversible gaps in our understanding of human prehistory.

One of the oldest human fossils found in Australia. Excavation was forbidden and attempts to protect the fossil failed. It was eventually destroyed by wind and rain

— Mungo Manic (@MungoManic) April 5, 2024

The remains of WLH 135 likely dated to 25-35 kya. It was discovered in 1986 in Willandra Lakes, between the… pic.twitter.com/xGZ215Yrz5

Research restrictions extend beyond physical remains. There is a growing movement to limit access to data and images that conflict with modern interpretations of the laws and customs of forager cultures. This includes restrictions on visual depictions of certain people, artefacts, and ceremonies; records of traditional practices; and archaeological field notes, photographs, and interviews. The significance of this loss cannot be overstated. Australia was one of the only places where humans maintained a hunter-gatherer lifestyle into the modern era, with an unbroken tradition lasting until 1984. This makes it an invaluable window into humanity’s past—a window that is gradually closing.

But despite the challenges, Australian scientists continue to preserve Australian forager languages, conduct limited excavations and genetic studies, and digitally archive many historical photographs and documents. The current trend of restricting access to fossils and historical materials will surely eventually end. When this happens, researchers will resume their investigations, albeit with fewer resources than before. Someday, hopefully sooner than later, Australians of all backgrounds will recognise the immense value of studying the foraging cultures of Australia and spark a renaissance of exploration into Australian prehistory.