Art and Culture

Tales of Creation and Adaptation

The journey of two novels from mind to page to silver screen.

Twenty years ago, a former agent told me that my upcoming young-adult novel, Chanda’s Secrets, about a teenager whose mother is dying of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, would be lucky to sell a few hundred copies to local high schools. Instead, by some freakish miracle, it was translated, published, awarded, and taught internationally, including in sub-Sahara. Even more amazingly, I found myself on the red carpet at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival for the premiere of its movie adaptation, Life, Above All. (The screening was followed by a ten-minute standing ovation, the film won Le Prix François Chalais, and it was later shortlisted for an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film.)

Last month, the new film adaptation of my psychological thriller The Dogs screened at TIFF Lightbox as part of the Female Eye on Film Festival. It has since been sold to Canada, Latin America, Germany, Austria, France, and Russia, and will soon receive US distribution.

My surreal experiences as a cork bobbing on rivers of serendipity got me thinking about various aspects of translation and adaptation: imagination transforms experience and intuition into prose that can be retold in different languages across cultures; narratives created in one medium can then be transposed into another. Naysayers notwithstanding, what makes these transpositions possible is the universality of human nature. It’s true that our specific experiences vary wildly, but people in related circumstances behave in similar ways no matter where they’re from. That’s why we’re able to see ourselves in stories written across continents and time.

By way of illustration, The Dogs is about a boy and his mother on the run from a violent father. They rent a farmhouse where the boy comes to believe that he’s communicating with the ghost of a child whose father murdered him on the property fifty years before. Is the ghost real or is the boy projecting his fears and cracking up under pressure? The story has a real-life inspiration—when I was a boy, my mother fled with me to my grandparents’ farm. Despite a fine reputation, my father was a sexual sadist who frequently choked my mother unconscious. I was once the rope in a human tug of war and was kidnapped for a few hours; the police were called. The link between my real and fictional worlds appears obvious.

Yet, curiously, I found it easier to write in the voice of Chanda, my fictional teenage girl in sub-Sahara, than I did in the voice of Cameron, my teenage alter-ego in southwestern Ontario. How is that possible? Where did Chanda come from? The answer may interest readers curious about the creative process and the practical aspects of bringing fiction and films to life.

In 2002, Rick Wilks, publisher of Annick Press, asked me over coffee if I’d like to write a novel to raise awareness about the AIDS pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa, with a portion of the proceeds going to the cause. I had helped to launch his young-adult division two years earlier with the novel Leslie’s Journal. Rick had wanted a playwright’s ear for dialogue; I’d thought translating my theatre background to fiction would be an interesting stretch; first-person narratives, which had become my specialty, are like extended monologues.

My immediate but qualified response was yes. I’d lived in New York during the ’80s AIDS pandemic and experienced firsthand the fear, hatred, stigma, and persecution that the “gay plague” brought to my community. Countless friends died horrific deaths. My friend Rob had three simultaneous cancers: a tumour in his brain that was making him blind and insane; another in his throat that choked him; and a third in his bowels that made elimination painful to impossible. Others had families who threw them out and refused to attend their funerals. I had night sweats (which turned out to be nothing), but was too terrified to get tested because the only available drug was useless and a positive test meant death. So yes, I could write about the human side of the pandemic from twenty years on the inside.

I was also angry about what was happening in sub-Sahara. At the time, seventeen percent of Botswana’s population had HIV, a figure that rose to 37.4 percent of pregnant women, and AIDS was the leading cause of death for teenage girls aged fifteen to nineteen. But this horror was next to invisible in the West. The little coverage it received turned human beings into statistics. Awareness was needed. No one listens to polemics or slogans, but stories get under the skin. A novel could put a human face to the pandemic and play a part, no matter how small, in a campaign for attention. A grain of sand is nothing, but enough grains of sand and there’s a beach.

Despite my enthusiasm for the project, I hadn’t been to sub-Sahara. But human beings are the same everywhere, and I was reasonably certain that the shame, stigma, terror, and denial that I’d experienced would also be the same, notwithstanding the massive cultural and economic differences between New York in the ’80s and sub-Sahara at the turn of the millennium. (I was right.) However, the pandemic mainly killed gay men and IV users in the West, whereas in sub-Sahara its victims were mostly heterosexual and the entire society was affected. I also had no feel for the cultural differences at sub-Saharan markets, social gatherings, standpipes, cattle posts, or funerals.

Furthermore, sub-Sahara has 49 countries and innumerable ethnicities with different, if overlapping, traditions. That itself wouldn’t be a problem as I’d be telling the story of a family living in a single community. (Novels aren’t info packages, they’re human truths found in character and plot.) But I’d need to fictionalise a specific community to avoid a false, stereotypical, pan-African gloss; and I’d need to experience it to properly convey the sensory details and authenticity of the novel’s world. Without that research, I felt the project would be impossible.

Luckily, Rick was in touch with Barbara Emmanuel, a senior policy advisor at Toronto Public Health. She and her colleagues were twinned with counterparts in Francistown, Botswana, one of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities’ best health-practice partnerships. The FCM would provide my travel and introductions to Solomon Kamwendo, a young theatre director who’d created Ghetto Artists, a troupe of teens and twenty-somethings who did street improvs to promote testing, and Patricia and Tebogo Bakwinya who founded and ran the Tshireletso AIDS Awareness Group—the Shining Stars of Monarch. The Shining Stars were children, in Patricia’s words, “preparing for orphanhood.”

Botswana was one of the hardest hit countries on the continent, but it was also one of the most progressive in promoting AIDS awareness, unlike neighbouring South Africa. There, then-President Mbeki gave a speech in which he said, to paraphrase: “The West already hates us. If we say AIDS is an African problem, it will be one more club for them to beat us with.” His point was identical to that of gay activists in the early ’80s who said: “Straights already hate us. If we say AIDS is a gay problem, it will be one more club for them to beat us with.” But Botswana and icons like Nelson Mandela were like America’s Larry Kramer and ACT UP. Our communities were dying and we had to speak up because no one else would speak up for us.

The thing that most surprised me upon my arrival in Botswana that summer was the prevalence of Internet cafes and cell phones enabling rural areas to leapfrog landline infrastructure. But what our media had also missed was the energy, camaraderie, and agency of the people. It was the same spirit I remembered from my own community in the ’80s—we learn to survive ongoing horrors like plagues, inner-city violence, and war zones by living for the small joys in daily life. This determination to focus on friends, family, and community was particularly true in Monarch, the poorest and roughest part of Francistown and home to the Shining Stars, where I conducted most of my research.

Patricia Bakwinya, with whom I’ve stayed in touch, is a ball of energy. She’d noticed a lot of kids wandering around her neighbourhood with nowhere to go. Realising that their parents were likely dead or dying of AIDS, she invited three of them to use her father’s home as a refuge; within a month, there were 36 kids and the yard was overflowing. Patricia sought the city’s permission to turn a plot of land down the road into a playground. Neighbours objected and officials turned her down, fearing the area would become known as an AIDS epicentre, which would destroy property values. “So,” she said, “I went on the night train to the capital and arrived at the Office of the President first thing in the morning. He wasn’t there, and I didn’t have an appointment, but they sent me through to the vice president who phoned all the relevant authorities in Francistown—the same ones that refused me—and that afternoon when I arrived back home, I had the plot.”

Patricia’s “playground” had since developed into a fully fledged centre with volunteers who taught kids and teens how to sew and bake bread in an on-site kiln so they would have the skills to earn an income when their parents passed away. In addition to a soccer team and other activities designed to provide friendship and emotional relief, there was an AIDS education program so the kids would know how to stay safe within infected homes where bloody diarrhoea and open sores were common. Wisely, Patricia placed no restrictions on who could come to play and learn, so children would not be marked as coming from a family with AIDS.

Dumilano was an eighteen-year-old volunteer at the centre. She was HIV-positive and had a toddler infected at birth. Her status was a secret except to Patricia and myself. “I don’t know how to tell my parents that I’ll be dead soon. I don’t know how to tell them their grandson will be dead soon. I volunteered here so that when I die, there’ll be somewhere people know him and love him.” She paused. “If I can live four more years, he will be six. If he is six, he may have a chance.”

Patricia and others introduced me to neighbours with HIV/AIDS diagnoses under wraps. I met a woman, thin as a rake, who reminded me of friends in hospice. Her husband had died. She handed me his doctor’s notes. “Night sweats… bloody diarrhoea…” She had five children. Her eldest daughter fetched the family’s water from the local standpipe, but she still chopped firewood, and when we met, she was bathing her youngest in a metal tub in the front yard: “I keep going because I wake up.”

I went to COCEPWA (Coping Centre for People with AIDS), an organisation for those overcome by stress. It brought them to its site in an unmarked car, and they entered through the back door. Rogers Bande, the director, told me that the shame and stigma of HIV/AIDS were so severe that despite Botswana’s huge number of infected, only seven would speak to the media: “They all live behind the curtain,” he said. (In sub-Sahara, curtains are often used between rooms to encourage air flow.) “It sounds like what we’d call the closet,” I said. He nodded. Fear of testing was equally strong. The young actors at Solomon Kamwendo’s Ghetto Artists were all part of the demographic most at risk and their job was urging people to get tested. But when I asked the group if they’d been tested, only one raised a hand. It was a choice I understood first-hand.

Solomon took me to a funeral home. It had been a building supply centre but there was more business in death. I saw an unfinished waiting room with a small aquarium, a coffin showroom, and a wall of refrigerators at the back, sometimes double occupied. Behind a curtain, there was a room stacked to the ceiling with children’s coffins made of spray-painted pressboard and finishing nails, with decorative tin handles glued to the side and bunting stapled to the interior.

It was a gut punch. I immediately knew that this was where the story had to begin. A sixteen-year-old girl comes to arrange the funeral of her baby sister. Her mother has AIDS, the cause of the baby’s death, but the girl doesn’t know.

There are different ways to translate experience into fiction. I use acting techniques to get inside the head of each character, turning scenes into one-person improvs. To sketch this method in practice: I imagine I’m the girl, let’s say my name is Chanda. I need to get the funeral arrangements for my sister over fast or I’ll fall apart. But the funeral director is busy, so I need a distraction. I see the aquarium across the waiting room and go look at the fish. But I keep seeing her face. I feel guilty. She’s been sick ever since she was born. Last night she cried so much, for a second I wished she was dead. I worry this is my fault.

Now, I’m the funeral director: I want to complete a business transaction. When I enter, I’d offer condolences, apologise for the delay, and ask if we’re waiting for parents so I don’t waste time. Now I’m Chanda: I’m upset the director thinks my parents should be here—I’m sixteen after all—but I tell him Mama was grieving too hard to come and make up a story for my step-Papa who didn’t come home last night. Et cetera.

Characters are based on an author’s ability to translate their experience and intuitions into fiction, but they also develop lives of their own. For instance, when the funeral director asks about Chanda’s parents, she could have said her Papa has passed or covered for him. But for some reason, I found myself typing the word “stepfather.” Suddenly, there were questions to answer. What’s their relationship? What happened to her father? Who are her neighbours and best friend?

That’s how I discovered Chanda’s best friend, Esther. I had met dozens of AIDS orphans. Three teenage brothers stood out. Their father had officially died of tuberculosis. When their mother was dying, officially of pneumonia, they were sixteen, fourteen, and twelve years old, respectively. They asked her to make a will and leave the home to them. “Our aunties and uncles had been talking about dividing us up, and we wanted to stay together as a family.” I met them two years later. Their home looked as might be expected from three teenage boys, but the eldest had gotten them to school and made sure food was on the table. Not all kids are so lucky. Some are considered dirty because of how their parents died. I met a nine-year-old forced to live in a dirt-floor aluminium shed; her grandmother used her orphan food basket, provided by the government, to feed the rest of her family, and her uncle abused her.

Esther’s situation was suggested by a range of similar stories; it also made dramatic sense to counterpoint Chanda’s. Esther is a teenage AIDS orphan separated from her younger siblings and abused by relatives who consider her and her family unclean. If I’m Esther at sixteen, I know the only thing that will make life worth living is getting my family back. That will take money, and the only way I can get it is to sell myself to truckers or men in town on business for the mines, government, and NGOs. So, I’d hang out in front of the hotels or at the park where trucks stop across the road: I’d tell myself this is only for now, just to get my brothers and sisters back; if I die it can’t be worse than what I’m living.

I saw those hotels and public parks with girls like Esther, and talked with people at each setting in the novel—a rowdy, friendly group at the walled-off, open-air shebeen where Chanda’s stepdad drinks sorghum home brew; nurses who wanted to show me the overcrowded hospital; the herbal doctor whose mud-walled office was full of framed sales awards made to look like diplomas; Solomon at his family’s cattle post where Mama goes to die. I was also grateful to be invited to a laying-over (wake); the funeral the following day at a cemetery field filled with single brick markers; and a faith healing at a one-room cinder block church. I met spirit doctors, one of whom threw slices of cattle bone to read my future. (I’d previously had a Santerían purification ritual in rural Cuba; the similar sense of spiritual power was extraordinary.)

I saw parallels everywhere. My friend Rob, for instance, opted for the lure of herbal remedies. (His symptoms became the cancers that killed Esther’s mother.) The convulsions of the would-be faith-healed at neighbourhood churches were the same as those of Pentecostals I’d seen slain in the Lord. The laying-over, a drunken all-nighter, was no different from an old-fashioned Irish wake. Even basic pull-toys were the same, with little trucks fashioned from hangers and the ends of pop cans for wheels. It’s further proof that stories focused on our common humanity have wide application. Chanda’s Secrets is set amid the sub-Saharan AIDS pandemic, but its broader, universal theme is the destructive power of secrets and the courage to live with truth.

Patricia has since given me updates on some of the Shining Stars I mentioned. Dumilano, the volunteer with the two-year-old, was strangled to death by a new boyfriend who then committed suicide. Her child survived and is now in his twenties. The three teen brothers who raised themselves are in their thirties and doing well. It is thought the eldest contracted HIV when tending to his mother. He discovered he was positive when he fell ill, but he is being treated with antiretroviral drugs and he now has a wife and family. The middle brother moved back to a family village where he’s built a nice house and runs a kiosk. The youngest earned a Masters Degree in Accountancy and is helping to take care of them.

As the sights and sounds of a world grow in the imagination, and questions lead to more questions, scenes suggest themselves and stories take shape. But communicating those stories requires the magic of writing and reading. Words are simply an arrangement of sounds. Text is a translation of those sounds into squiggles known as letters. Writers communicate the stories in their heads into sounds (words) translated into squiggles (text) and readers decipher those squiggles back into sounds/words they hear/understand in their heads. It’s an entirely abstract process but one with real physiological effects. These squiggles make us laugh and cry at characters and stories that only exist in our minds and forge a living connection between readers and an author, who may be dead.

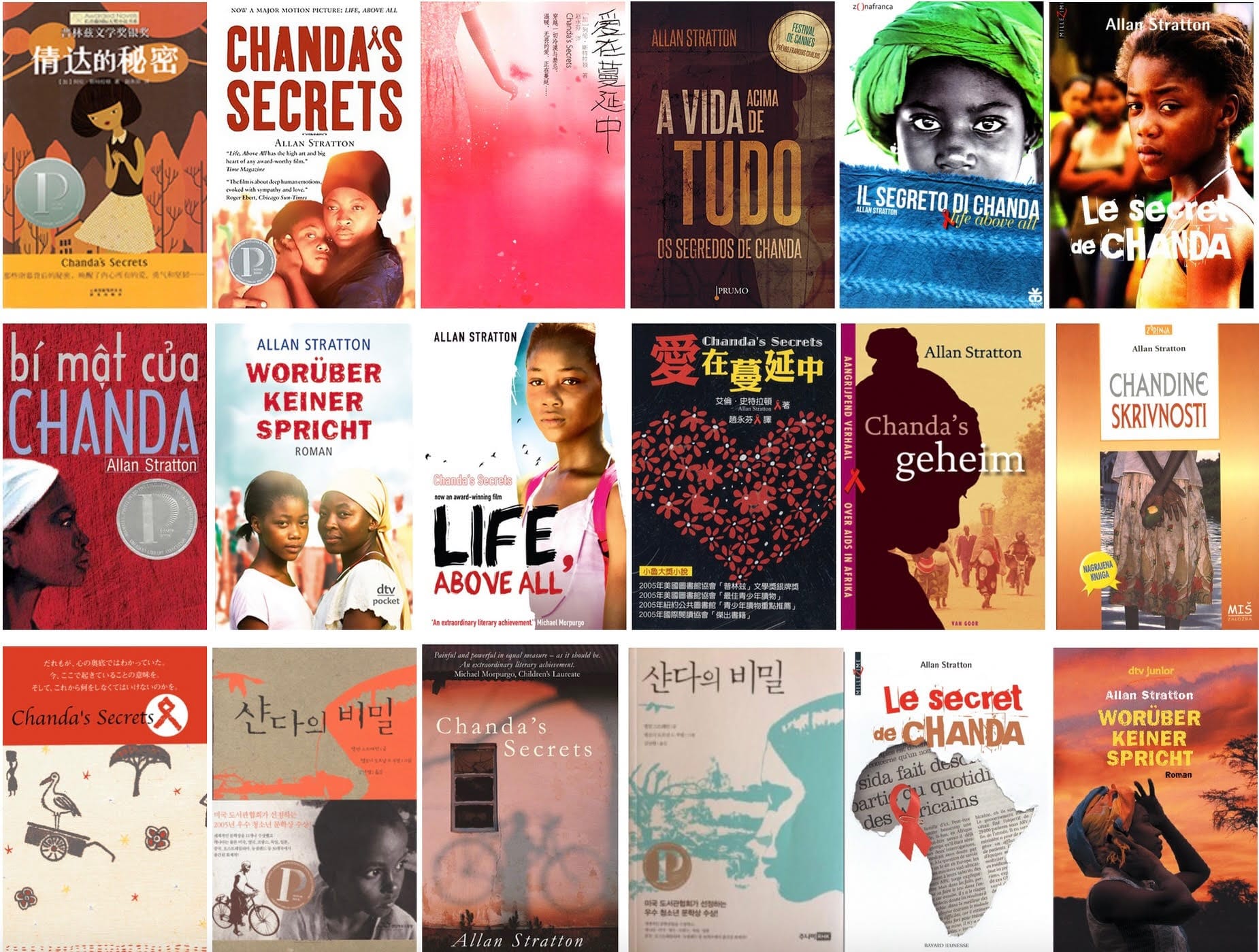

I sent a draft to many of the people I’d worked with to check for authenticity. The edited text went to press soon after and was launched at Toronto City Hall with members of the FCM who’d arranged my travel and their colleagues in Botswana. Stephen Lewis, the UN Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa was an enthusiastic champion. It was the first of several young-adult novels to raise awareness, and it was soon translated by publishers around the world. Further magic, for the words that moved readers in other languages were incomprehensible to me; especially when the squiggles themselves were foreign, as in the Japanese, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Korean editions.

Because of all the foreign editions, I’ve had the chance to compare how book covers translate a novel’s meaning to their respective cultures. I don’t want to overstate stereotypes, but it’s curious that the British cover reflects emotional reserve: it shows the shadow of a girl next to an impenetrable window. The German cover projects the individual versus nature: a strong girl in the foreground against a vast African sunset. The French cover is political: a newspaper column on AIDS torn the represent the shape of Africa. The Japanese cover is spare with artful woodcuts, and so forth.

It’s both strange to know that one is communicating with people from cultures different from one’s own and reassuring that connections like these can cross divides. But in this case, the effect on the lives of affected children has meant more than anything. A teacher from a small village emailed to tell me that one of her students was a fourteen-year-old who had been acting out. His parents had died of AIDS two years before; because of stigma, he had pretended it was because of tuberculosis and pneumonia. He saw the book and asked to take it. Days later he returned and said, “Ma’am, I was lying on my bed reading the book and the sun was shining in the window and I suddenly realised I was crying. Ma’am, I haven’t cried in two years.”

The teacher reported that her student began reading the novel aloud to his friends who had lost parents to AIDS but had been unable to fully grieve by speaking about how they’d died. But they were finally able to talk about their loss through the experiences of Chanda. In a moving irony, a novel written to provide Westerners with a human face to the AIDS pandemic in Africa, became grief therapy for the orphans at its heart.

I was surprised and delighted when producer Oliver Stolz, head of Germany’s Dreamer Joint Venture, told me he’d like to adapt Chanda’s Secrets into a movie. We’d met earlier when he was in Toronto for the Hot Docs screening of The Lost Children, his documentary about Uganda’s child soldiers. I was researching the Lord’s Resistance Army for a novel and emailed to see if we could meet for coffee. He said sure. Afterwards, I handed him a copy of Chanda’s Secrets by way of thanks, never expecting to hear from him again.

A year later, I was in Berlin doing a book tour for my German publisher, dtv, and Oliver invited me to dinner with Oliver Schmitz, an award-winning South African director who had emigrated to Germany to avoid his country’s apartheid draft. We talked about what was important in the novel and what could go. They asked me if I’d like to write the screenplay but I declined. I wanted to work on new novels, so I recommended Dennis Foon, a superb screenwriter I’d known for decades, who had a particular gift for writing children’s roles. (Like Schmitz, Dennis had emigrated to avoid the draft, in his case to Canada from the States because of the Vietnam war.) Dennis was soon on board and began his own research as the project took shape.

Dennis’s screenplay was translated from English to Pedi for the shoot. Pedi is fourth of South Africa’s eleven official languages and the one spoken in Elandsdoorn where the roles of the children, minor characters, and extras were cast. The lead adult actors were brought in from Cape Town, South Africa’s major production centre, where the majority speak Africaans, Xhosa, and English. The tech crew was German. The common language on set was English.

It’s rare that novelists are included in the filmmaking process; we can be a pain in the neck if we find we are unable to surrender control over our brain babies. But the producers on both Life, Above All and The Dogs were equally generous. I was shown drafts of the screenplay, asked for comments, and invited onto the set. For The Dogs, I was even consulted on casting and given a walk-on part. The experiences have given me a special appreciation of the challenges of translating between media.

Both films were faithful adaptations of my work, but no film can replicate the scope of a novel’s narrative and cast list. (Authors don’t need to worry about paying for sets and casts of thousands.) In addition to which, print and film have different strengths and weaknesses and there are practical matters that affect a shoot. Financing dictated relocation of the settings. An investment program to develop a film-production industry in northern Ontario meant moving The Dogs from its fictionalised Bruce County roots. And the Francistown of Chanda’s Secrets was switched to Elandsdoorn, South Africa, since Enigma Pictures, the South African co-producer, was based in Cape Town. The change also made sense given Oliver’s South African citizenship and professional roots. These locations had a different look to those described in the novels, but it’s the heart that counts, and both teams captured each story’s respective content and tone.

Financing was a more critical issue for The Dogs and led to changes in director, cast, and screenplay when a key component suddenly fell through ten days before principal photography began. It took a year to put the pieces back together. To forestall a second collapse, the producers began shooting in late fall rather than wait for spring, a gamble given the weather on location in northern Ontario. A snowstorm in the final week required rewrites the morning of a key scene. Weather was also a concern for Life, Above All. The first weeks were shot just after the dry season, and precautions were taken to protect the German film equipment from gusts of dusty air. After a month’s break over Christmas, the shoot wrapped in the rainy season which had its own complications for continuity.

Oliver deliberately shot the first half of the story last with a holiday gap. This allowed Lerato Mvelase, who played Chanda’s mother, to lose weight for the later scenes when she is sick, and then put it back on over Christmas and return to play the earlier scenes when she is healthy. But no one considered that our Chanda, twelve-year-old Khomotso Manyaka, might have a growth spurt. Sure enough, she returned to the shoot after the break a bit taller and with newly developing breasts. Thankfully, because we see what we expect to see, audiences never noticed.

I was dubious about the decision to change Chanda’s age from sixteen to twelve. In the novel, Chanda is in contention for a scholarship that could lift her family out of poverty, but she quits school when her home life collapses. In her mother’s absence, she also struggles with Mrs Tafa, her mother’s bossy friend, for control of decisions about her younger siblings. Both factors raise the stakes for Chanda and add to her character’s complexity, but neither makes sense for a pre-teen. Nevertheless, Oliver and Dennis were right. Those aspects of the story could be cut, and visually, a twelve-year-old’s vulnerability has greater impact. This applied even more to Esther and the horror we feel when she enters a trucker’s cab and then returns to Chanda beaten and bloodied.

The only other significant change was the ending. In the novel, Chanda sees a stork in her yard and talks to it for company. The night her mother dies, the bird reappears and she and her siblings see it from their window. The bird circles the yard and flies off. Her brother says, “That was Mama, wasn’t it?” and Chanda tells the reader: “My mind said no, but my heart said yes.” An epilogue follows as Chanda and her siblings handle their grief, supported by the love and loyalty of Mrs Tafa, Esther, and the community. However, in the movie, when Mama dies, Chanda hears singing outside. She opens the front door and sees her neighbours. Their singing increases in volume as the camera dollies into a tight closeup on Chanda’s enigmatic face.

In the novel, the first-person narration allowed the metaphor of the bird to be read in various ways, and the epilogue provided a gentle weight of completion. On film, however, that ending would have required CGI effects followed by a series of choppy, anticlimactic scenes. The power of the choir against Chanda’s face, on the other hand, worked beautifully in the film in a way that it could not have worked on the printed page.

In the end, my only complaint about Life, Above All was the change of title. The film went by Chanda’s Secrets throughout production, but at the last minute, the director and producer were persuaded by a Cannes contact that it should be altered lest audiences assume it was about a woman having an affair. Trust the French. So, the night before the Cannes lineup was announced, they came up with Life, Above All, a title that, for me, evokes maudlin violins. Anyway, that’s how it was released internationally by Sony Pictures Classics, except in France, where it was retitled Le secret de Chanda. Again, trust the French.

Director Valerie Buhagiar and screenwriters Anthony Artibello and Sheila Rogerson faced a different challenge when translating The Dogs to screen. When Cameron communicates with Jacky, the ghost of the child he believes was murdered at the rented farmhouse where he and his mother have moved, he may or may not be having a psychotic break. This ambiguity is central to the novel’s dramatic tension. Writing the novel in first-person, present-tense, I simply reported my experiences as Cameron. In one episode, for instance, I listened to Jacky as he recalled a terrible fight between his parents, then reacted defensively when my mother entered my room to see who I was talking to.

Achieving that on film was trickier. Anthony and Sheila wrote the fight as a flashback intercut with a parallel scene in which Cameron’s mother hears him shouting, goes to his room, and is horrified to see him beating himself in a fugue state. (To distinguish the real and ghost worlds, Valerie and colourist Drake Conrad simulated a Technicolor effect for Jacky’s flashback.) Another alteration used visuals to make a plot point. In the novel, Cameron’s father finds him when he gets a Google Alert that links to an anti-Cameron website created by school bullies. In the movie, student videos of a fistfight Cameron had with his chief enemy end up on YouTube.

Friends tend to assume that a film adaptation is validation for a novelist. In fact, we’re mostly control freaks for whom writing is a way to impose order on an otherwise chaotic world. Emotional detachment from projects controlled by others is important. If a film is terrible, it will disappear; the book will remain. On the other hand, a successful adaptation can extend a book’s reach. That was the case in sub-Sahara when Life, Above All swept the 2011 Golden Horn Awards, South Africa’s film and television equivalent of the Oscars/Emmys. It won best feature film, director, actress, supporting actress, ensemble, screenplay, and costumes. Chanda’s Secrets was already in schools, but after it was reissued under the film’s title by an educational publisher, it was distributed for study in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and Swaziland.

That schools in South Africa are now teaching a novel by a Western author about AIDS orphans in sub-Sahara provides a rebuttal to two destructive edicts promoted by progressive ideologues: the appropriation heresy—that writers cannot imagine life beyond their specific demographic group—and the promotion of trigger warnings, which, aside from making audiences more anxious, reinterpret an instrument of healing as an agent of harm. Fictionalised trauma creates an imaginary space for reflection and growth. That’s why Jews create and read stories about the Holocaust; why gay men create and read stories about the closet; and why AIDS orphans read and discuss stories about lives like their own.

Everyone owns their own imagination, which is where the most important translations take place. Words on a page and images on a screen are manifestations of our dreams, the often-subconscious meanings of which are left to be discovered by each of us depending on our experience and understanding. That interplay, between minds and media, is what makes art and the artistic process so exciting.