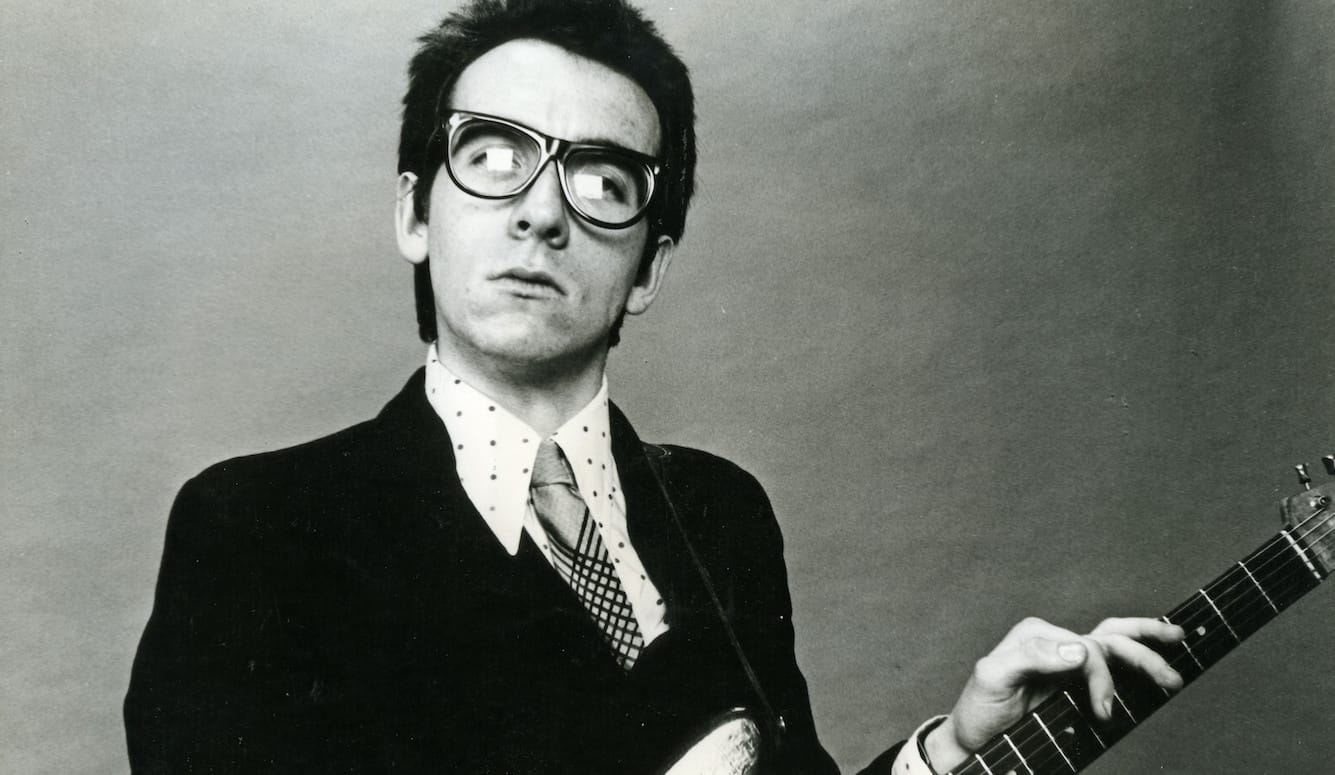

As Elvis Costello enters his eighth decade on 25 August, it is sobering to reflect that he has now been a part of our musical furniture for almost half a century. He always looked older than he was, even at the beginning. Between the suit, the Buddy Holly spectacles, and the short hair in those first months of punk-whipped ’77, he more closely resembled a bank clerk than a rock star, and it was only when he opened his mouth to sing that it became apparent just how misleading the image was.

At a time when everyone, it seemed, was striving to outdo one another in the Angry Young Person stakes, even Costello’s love songs (and “Alison” was sweet enough that even Linda Ronstadt covered it) made the rest of the pack sound merely irritable. As Costello himself put it in 1977, “The only two things that matter to me, the only motivation points for me writing all these songs are revenge and guilt. Those are the only emotions I know about, that I know I can feel. Love? I dunno what it means, really, and it doesn’t exist in my songs.”

In an interview with The Herald in 2002, he would look back on that remark and admit, “That was just something I said when I was drunk.” But, he continued, “I kind of like it, because it’s a simplification of something that was essentially true.” And if his records sounded furious, his live shows positively seethed. Nevertheless, the image really wasn’t all that misleading. Born in west London, raised in Liverpool (his mother’s home town), and then back to London in the early 1970s, Declan McManus (as he was then) did indeed work as a bank clerk for a while, although he was trained as a computer operator—a career he pursued until the eve of his first album’s release.

He was a married man—and the father of a son, too—at a time when happily married rock stars were still considered rare enough that record companies tended to ignore it, fearful of alienating fans. Whether or not that would have mattered in Costello’s case remains one of the era’s great unanswerables. As a musician, he first appeared on at least a few people’s radar as a member of Flip City, one of the myriad bands that flirted with the capital’s pub-rock scene in the early–mid 1970s. They did not get far. Future historians would look back and marvel at the songs already in Costello’s repertoire at the time—“Radio Radio,” “Living In Paradise,” and “Miracle Man” would all become high points on his first two albums. But Costello’s recording debut was accompanying his dance-band musician father Ross McManus on a lemonade commercial, and his only radio appearance of note came when DJ Charlie Gillett played a couple of his demos on Radio London one day.

But Dave Robinson, a feature on the London club scene since the Sixties, and owner of a cheap recording studio in Islington, was a fan from the moment Costello booked his first session there. And when Robinson co-founded the Stiff Records label in mid-1976, the newly renamed singer/guitarist was one of its first signings. Costello’s first single, “Less Than Zero,” was the label’s eleventh release, released in mid-1977 ahead of his debut LP, My Aim Is True. On paper, the album was as incongruous as its maker’s appearance. Costello was accompanied in the studio by Clover, a London-based American country-rock act best remembered today for various members’ future involvement with the Doobie Brothers and Huey Lewis and the News.

My Aim is True, however, was pure Costello. Recorded in just 24 hours with producer Nick Lowe, it was literate, smart, snarling, and open-ended enough that he could just as easily have performed the songs solo. Or translated them into the pounding punk/R&B miasma of the Attractions, the band with whom he hit the London pub circuit at the end of April, and with whom he would go on to create two of the most significant albums of the next couple of years: 1978’s This Year’s Model, and the following year’s Armed Forces.

The Attractions themselves were not without their own track records. Bassist Bruce Thomas hailed from the Sutherland Brothers and Quiver, a band best remembered today for providing Rod Stewart with his hit “Sailing,” but a most capable outfit in their own right—guitarist Tim Renwick subsequently worked with everyone from TV Smith to Pink Floyd, and for a long time was Al Stewart’s guitarist of choice. Drummer Pete Thomas (no relation) had played with the mighty Chilli Willie and the Red Hot Peppers. Keyboard player Steve Nason was the only one with no past professional experience, hence the stage name with which a passing Ian Dury gifted him... Nieve, pronounced “naive.” Together, however, they gave Costello the accompaniment that even his most rancorous compositions demanded.

The “Red Shoes” single, released in the summer of ’77, gave Costello his first national television exposure when he appeared on the BBC’s weekly pop flagship Top of the Pops in August. Three months later, the darkly reggae-fied “Watching the Detectives” broke him into the UK Top Twenty.

Touring the UK with his label’s Live Stiffs package of acts (Ian Dury, Wreckless Eric, and Larry Wallis were also billed), Elvis Costello and the Attractions stole the show on a nightly basis (although Dury and his Blockheads ran them very close). And in December, the band crossed the Atlantic to appear on US TV’s Saturday Night Live. They were last-minute replacements for the Sex Pistols, who had been booked onto the show but were unable to appear as immigration problems delayed the start of their American tour. But if middle America thought it had been spared the sight of the foul-mouthed yobs the media had led them to expect (because Elvis wore a suit for the occasion), they had another think coming.

Costello was scheduled to perform “Less Than Zero,” but he cut that number short and the band lurched into “Radio Radio” instead, his still-unrecorded indictment of broadcasting that had been on his mind since Flip City. Rebroadcast during SNL’s 25th birthday celebrations in 1999, the performance seemed tame by the standards we had grown accustomed to—from both Costello and from broadcast media. Its impact was further reduced when Costello re-enacted the moment during that same anniversary shindig, interrupting the Beastie Boys’ performance of “Sabotage” and leading them, instead, through another version of “Radio Radio.”

Back in 1977, however, Costello’s sleight of hand was greeted with outrage, astonishment (the Village Voice dubbed him the “Avenging Dork”), and threats that he would never appear on American TV again. But he probably didn’t care. Across the nation, awestruck viewers effectively adopted him as the embodiment of all this “punk rock” business they’d been reading about. Even the skinny tie he routinely wore became a fashion statement.

Elvis Costello and the Attractions made landfall in America like a hurricane, and throughout that winter of 1977–8, they never stopped. No matter that he loathed the over-cooked remix of “Alison” released as his first US single. Honed to perfection by a solid year of British gigging, that tour saw the Attractions capturing all the nuances of their studio repertoire, but with an added edge of manic excitement that perfectly complemented the bitterness of Costello’s subject matter.

With the My Aim is True material already sidelined by the brutal, brooding This Year’s Model, Costello and the Attractions were putting on some of the greatest shows of their careers. With “Night Rally,” “The Beat,” “Lipstick Vogue,” and imminent hit singles “(I Don’t Want to Go to) Chelsea” and “Pump It Up,” Costello’s repertoire was political without the pontification; raging without raising its voice; danceable without a dance beat.

Catch any one of the manifold bootlegs from that year. From the lyrical reinventions that gave “Less Than Zero” even more edge than before, to the occasional covers that fell into the show—Ian Dury’s “Roadette Song,” Peter Tosh’s “Walk, Don’t Look Back,” Richard Hell’s “Love Comes in Spurts”—and on to carnivorous assaults upon his own repertoire, an Elvis Costello concert was less a musical experience than it was an hour-long diatribe in dub, set to a compulsive soundtrack. “This song’s called ‘I Don’t Want to Go to Chelsea,’ but you can make it any place you want.”

The original title of Costello’s third album was Emotional Fascism, a theme that ran through the record even after the title was changed. Certainly it made an awkward companion to the world’s other favourite albums that spring of 1979, but still Armed Forces broke into the US Top Ten, the most successful album yet to come out of Britain's new wave.

Those three albums remain one of the most powerful and self-affirming trilogies in rock history—indeed, for listeners who were there at the time, they are effectively a time-capsule; a recollection of how exquisitely Costello’s songwriting dovetailed into the sociopolitical mood of the times, particularly in the UK. A country going broke, neo-Nazi politics on the rise, youth culture splintered into warring schisms… even rose-tinted hindsight cannot manipulate those memories into “the good old days,” and those old Elvis albums only amplify the dread.

Struggling out of the post-punk malaise that draped late 1970s Britain, a ska revival cloaked itself in post-punk agitprop and burst exhilaratingly onto the circuit. The Specials led the pack, but Costello would swiftly place himself alongside them at the forefront of the movement, not only by briefly releasing his own next single, “I Can’t Stand Up For Falling Down” on that band’s 2-Tone label (prior to forming his own F-Beat imprint), but also by stepping forward to produce the group’s debut album.

For the Specials, the choice of Elvis Costello as producer was contentious. On one hand, Costello famously informed the band that they didn’t “need that punk rock guitarist”—a clear indication that the group’s true musical intent escaped him. On the other hand, he was perfectly in tune with the Specials’ ambitions and ideals—indeed, as far back as his own fascist-baiting debut single “Less Than Zero,” Costello was a niggling thorn in the far-right’s juiciest flank, all the more so for the apparent ambiguity of his finest jabs.

Tracks like “Goon Squad,” “Night Rally,” and—absurdly—“Oliver’s Army” were each singled out by knee-jerk simpletons for lyrics that could be (and, especially in the US, frequently were) misconstrued as racist rallying calls. Costello’s ability to withstand those attacks and keep coming back for more was one of the reasons that the Specials chose to work with him. Costello himself intuitively recognised the band as like minds in the making and saw the confrontational even-handedness of their own lyrical stance in direct relation to his own.

As band member Neville Staples put it, “Jobs were terrible, you couldn’t get no jobs. Housing prices were shooting up. … We were saying something, there was a sense of being. But we weren’t trying to change things, we were just saying what we saw. We were in a position to do that. We could sing about it because it was what was happening in the place, and people would hear it and maybe understand it because it was happening to them at the same time.”

Costello, however fleetingly, was to play an integral part in delivering that message. But he was also ready to move on. He had never made a secret of how widely his musical tastes and ambitions were spread (the country-styled “Stranger in the House” was as likely to appear in his live repertoire as the punk assault of the Damned’s “Neat Neat Neat”); now he wanted to demonstrate that. “The focus of those first records was narrowed down very consciously to make a statement, to burn some earth around me: don’t come into this circle, y’know?” Costello later reflected. “And it worked, very effectively, to the extent that it took five albums for people to realise that there was anything else going on.”

Or, as he remarked on another occasion, “You overlook the fact that it’s only writers that sit at home and go, ‘What did he mean by all that stuff?’ and we’re going, ‘Ha, they bought that one again! Let’s kick down another door!’ After about five years, you start to realise it’s a bit childish.” 1980’s Get Happy!! would mark the end of Costello’s “angry young man” period—a less pointed and more commercial collection of songs that saw him finally shaking off the “new Bob Dylan” tag that had attended him thus far, and move towards “new Van Morrison” territory—a distressing move for die-hard fans, but a necessary one regardless.

This maturity first bloomed on 1981’s Trust album; then finally sloughed off in the long-threatened direction of Nashville for the same year’s collection of country covers, Almost Blue. Recorded in Music City with producer Billy Sherrill, the album was previewed by a cover of George Jones’s “A Good Year For The Roses,” and also included Patsy Cline’s “Sweet Dreams” alongside a slew of perfectly styled Costello country numbers. So seamless was the record that, when Costello toured the US at the end of the year, his Nashville date took place at the Grand Ole Opry.

Nor was his appetite for change yet sated. In January 1982, Costello staged a London performance with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London before returning to the studio with the Attractions for the snarling back-to-basics LP Imperial Bedroom, followed swiftly by Punch the Clock the following year and Goodbye Cruel World in 1984. It was becoming increasingly apparent that a major change was in the air. “Costello’s 1983 American tour was so boring,” proclaimed writer Ira Robbins, “that even longtime fans found it difficult to remain alert for an entire set of pseudo-cabaret run throughs.”

So, it seemed, did Costello. “The very first solo [tour] I did was right before Goodbye Cruel World came out,” he mused in 1989. “I did it in America, and it was horrible, actually, because I found out how bad that record was, before it was released, but it was too late to pull it.” Leaving the Attractions at home, his next US tour saw him touring with T-Bone Burnett instead (the pair also recorded together as the Coward Brothers). His next single, “The Only Flame In Town,” paired him with co-vocalist Daryl Hall, while the album The King of America was recorded almost wholly with an all-American backing band, the Confederates—T-Bone again, plus James Burton, Jim Keltner, and others.

Costello’s restlessness remained paramount, domestically as well as musically. He had worked hard to keep his private life private, but of course his resolve was no match for any passing paparazzi who decided to take his picture. Nor was it any match for the infidelities that saw his first marriage, to teenage sweetheart Mary Burgoyne, break down briefly in 1978, and then permanently in 1984. The following year, he and Cait O’Riordan, the bassist with the Pogues, became a couple.

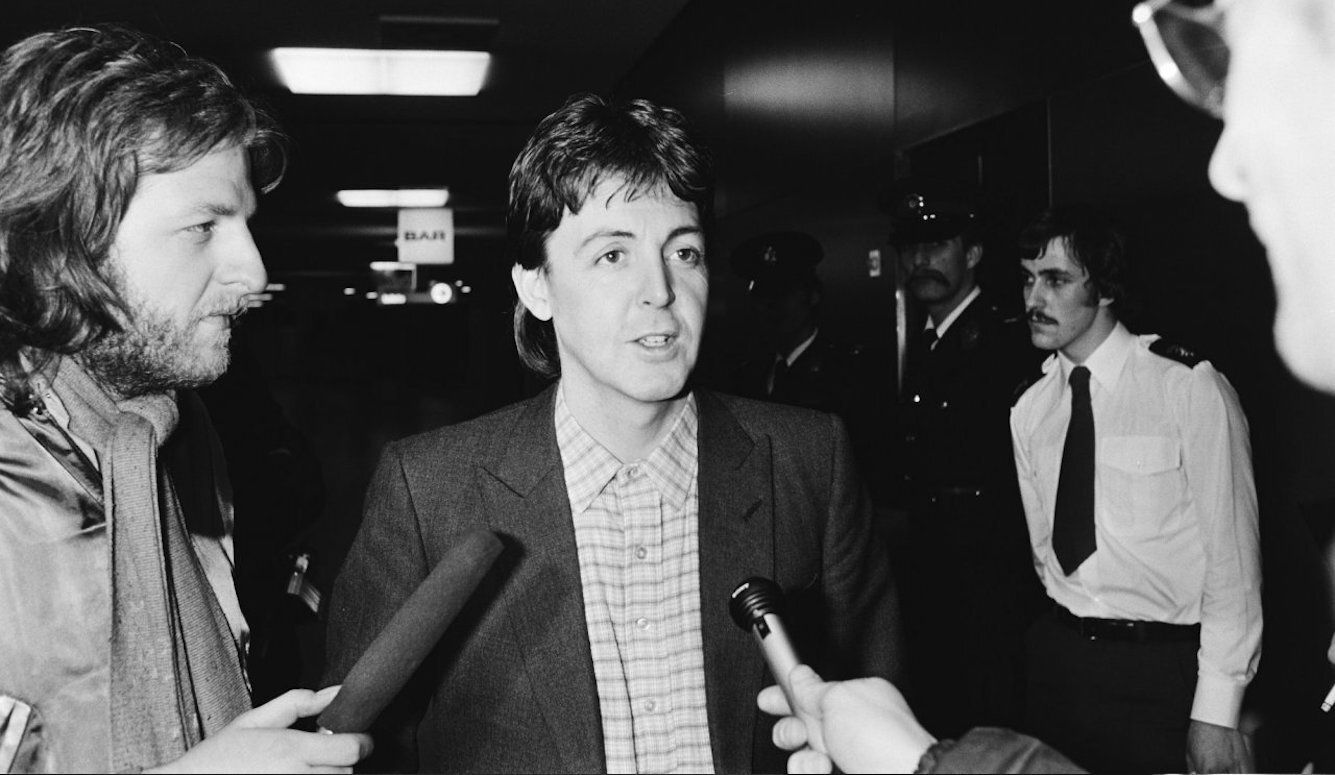

His talents, too, branched out. He made his acting debut in the mid-eighties movie No Surrender, and during a solo performance at 1985’s Live Aid festival, he performed a raw, unplugged version of the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love,” which he wryly introduced as “an old northern English folk song.” The Beatles connection then deepened as Paul McCartney’s 1987 b-side “Back On My Feet” introduced Costello as Macca’s latest songwriting partner. Indeed, if any single event could illustrate how firmly entrenched within the music scene Costello had now become, that was surely it.

Ten years earlier, he’d been playing west London pubs to a punk audience that spat at him (in the nicest possible way, of course). Now he was working on not one but two full albums with a performer his old fans used to dismiss out of hand. The collaboration produced McCartney’s Flowers in the Dirt and Costello’s Spike. The latter, incidentally, also featured contributions from Allen Toussaint, Chrissie Hynde, Christy Moore, Roger McGuinn and Mitchell Froom, though Costello denied that it should be thought of “as an all-star cast.” “There’s obviously a couple of names there that everyone’s going to talk about … and their parts are essential to the whole, but there are people who did more work on the record, and I think that should be acknowledged.”

Like Flowers in the Dirt, Spike was both a critical and a commercial success, but it was an artistic triumph too, for both of its creators. Certainly Costello proved to be McCartney’s most sympathetic songwriting partner since John Lennon, while one of the best of their collaborative efforts, “Veronica,” not only earned Costello an MTV award for the Best Male Video of 1988, but surely also contributed to his triumph in Rolling Stone’s Best Male Songwriter poll at the end of the year. Costello even returned to Saturday Night Live, for a very different performance to the one that caused such consternation all those years before.

“I know some people have very bad preconceptions about Paul McCartney,” Costello acknowledged at the time. “But I’m involved to the extent that I’ve written a bunch of songs with him. … I know he’s a really good bass player, so I’m not too bothered about what anyone thinks about him playing on my record.”

All decade long, it seemed, Costello had been deliberately testing the boundaries of his own musical capabilities as well as his audience’s tastes and patience. As the 1990s got underway, however, his precocity shifted into overdrive—an unexpected swerve, but in many ways a natural one, too. Across a career that had refused to stand still for more than a year or two (even the killer Costello of those first three classic albums pushed the biscuit for little more than 18 months), countless ears have bent around the ups and downs of his output, admiring this album while disdaining that. In the court of critical opinion, it sometimes felt as though he had either “blown it” or “made a comeback” with each new release.

In fact, it was easier simply to let Costello get on with things, rather than write him off because he had not yet rewritten “Watching the Detectives” again. Because, in many ways, it didn’t matter whether what he did was any good or not; Costello’s allure was that he kept moving, kept trying, and kept going, no matter what anyone else said about him.

Or did he? As he told Mojo in 2013, “Your natural curiosity leads you down trails and some of them are going to seem like false trails to people who liked you first. The penny doesn’t necessarily drop until a long time afterwards. You do something really different, people get horrified—the sky is falling!—and then 10 years later they’re telling you, ‘Oh, I get that now.’ You’ve always got people walking in and out of the door, unless you’re in the business of trying to rule the world and having as many people as possible like you for the most basic reasons. That’s not a musical vocation. That’s how you become Mussolini.”

It was only natural, then, that Costello should devote much of his next decade to further exploring that dynamic. And if he untied a few more of the umbilical cords that made him “Elvis Costello,” he told Q magazine in 1991, so much the better. “The longer you do this for a living, the more you just worry about solving your own problem and not worrying so much about whether it’s true or not that ‘the song is back’ or whether dance is everything, whether acid house is just like punk in sensibility—that’s just stuff to fill up magazines. It’s nothing to do with what I do, it’s irrelevant to me. It can be amusing if you listen to the records, but I’m not interested in it. I don’t follow that stuff anymore.”

Through 1991–92 alone, Costello contributed to a number of left-field projects: new albums by Sam Phillips and the Chieftains, a Grateful Dead tribute album, the soundtrack to the ten-hour UK TV drama GBH, and a version of the Kinks’ “Days” for the soundtrack to Wim Wenders’s movie Until the End of the World. Even by these standards, however, by far his most bizarre move—at least at the time—was his late 1992 union with the Brodsky Quartet to record a neo-classical record titled The Juliet Letters, a conceptual piece based on the true story of a professor in Verona, Italy, who answered letters addressed to one Juliet Capulet.

With Cait O’Riordan, Costello would also compose (in one weekend) an entire album for former Transvision Vamp vocalist Wendy James, the startling Now Ain’t the Time for Your Tears, with much of that album’s belligerence then resurfacing in his own next album, the aptly titled Brutal Youth. That record was made with the Attractions (renamed the Distractions for the occasion), who were back on board for the first time in almost a decade, effortlessly recapturing their clattering garage-punk glory. It was his harshest collection in years; an album, enthused Alternative Press, “[that] reminds us why we loved him in the first place, and why he still hates us in return.” That same love/hate dynamic remained in place when the same team reconvened for 1996’s All This Useless Beauty.

Intriguingly, too, Costello also appeared to be finally appreciating his role as an elder statesman of British pop, as he invited Lush and Sleeper, scions of the erupting Britpop movement, to contribute b-sides to his next two singles (Sleeper also toured America with Costello in 1996). He remained, however, equally interested in pursuing classic songsmiths. In 1996, he played live with jazz guitarist Bill Frisell; in 1997, he reunited with the Brodsky Quartet for a contribution to the Kurt Weill tribute September Songs. But his most significant step was surely an appearance on David Letterman’s show alongside veteran songwriter Burt Bacharach. Costello had been championing Bacharach’s music since his first UK tour in 1977, when “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself,” written by Bacharach and Hal David back in 1963, became a part of his live show.

The pair would work together again on the soundtrack to Grace of My Heart, and ultimately, across a full album, 1998’s Painted From Memory. Sufficient additional material remained to create 2023’s box set The Sweetest Punch: The Songs of Costello & Bacharach. One song from the album, “I Still Have that Other Girl,” landed the pair a Grammy for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals, while Costello was forced to make more room on the mantelpiece after another Grammy arrived for “The Long Journey Home,” his collaboration with Paddy Moloney of The Chieftains.

Other movie soundtrack work followed as did further songwriting collaborations and deeper dives into the classical canon with singer Anne Sofie von Otter and as artist-in-residence at UCLA. By July 2004, the London Symphony Orchestra was performing Costello’s ballet Il Sogno in New York. A new album, When I Was Cruel, appeared in 2002, followed by North in 2003, a record laden with piano ballads documenting the breakdown of his relationship with O’Riordan and his engagement to singer and pianist Diana Krall.

He recorded jazz standards with Marian McPartland; he joined Billie Joe Armstrong to perform a set of his own songs and Green Day standards; he cut a live album with the Metropole Orkest at the North Sea Jazz Festival; and he was commissioned to write a chamber opera by the Danish Royal Opera. It soon became apparent that any attempt to document all of Costello’s activities through this new century would be better confined to a series of spreadsheets than recorded with anything as mundane as pen and paper.

The jewels shone out regardless, and none so brilliantly as 2009’s Secret Profane and Sugarcane, a record greeted by some as Costello’s long overdue return to country music, but more accurately ranked among the most exhilarating Americana albums of recent (and, given its vintage, not-so-recent years). It is also one of his funniest. Costello has never disguised his sense of humour, regardless of how seriously the critics (and certain fans) felt they should take him. But even they might have cracked a smile at the album’s almost-title track, “Sulphur to Sugarcane,” as a disreputable travelling man dictates his observations on the opposite sex:

The women in Poughkeepsie,

Take their clothes off when they’re tipsy,

But in Albany, New York,

They love the filthy way I talk.

It’s not very far, the song says, “from Sulphur to Sugarcane.” But it’s a helluva long way from “Alison” and “Pump It Up.” And that’s probably the key to how and why so many people have remained loyal to Costello, no matter where his muse might take him, or where he will follow it in future. Of the 33 studio albums Costello has released to date, just five post-date Secret Profane and Sugarcane. Each one is unique, most of them are surprising, and Spanish Model is so bizarre that it can only be described as brilliant—the original backing tracks for This Year’s Model are laid down behind Spanish language translations of the songs, all of which are performed by guest vocalists.

Perhaps Declan McManus’s most remarkable contribution to the world of Elvis Costello, however, was his long-awaited autobiography, Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink, published in 2015. It’s particularly remarkable because, had Costello vanished from view immediately after making My Aim Is True, the book would still be more than half its final length. Which is not a condemnation; merely an observation. Even as it stands, sprawled across 670 pages, Costello delivered a beast to be proud of; a rip-roaring ride through… well, let’s see.

The serial infidelities of his father. Serial infidelities of his own. A lot of Beatle-based name dropping. A teetering pile of albums that add up to a worthy career, if not an absolutely brilliant one. And an unhealthy fascination with “Stairway to Heaven”—unhealthy because the first time he mentions it is midway through a story about how he almost got punched by Robert Plant. But that doesn’t stop him mentioning it again. And again. Sometimes, he even forgets to smirk.

The first half of the book is best, which may be why he lingers on it for so long. But maybe Costello would also like us to forget that after that extraordinary run of early albums, he dropped some utter clunkers. Or maybe he just remembers writing and recording those early songs more clearly. Just as he remembers the first tours, the first controversies, and the first groupies more clearly. Or maybe things just matter more when you’re young. Even Costello seems in awe of what a powerful live machine the Attractions were in the first flush of the band’s youth, an incandescent blur of snot, spite, and spit that could make the Ramones sound sluggish and Johnny Rotten sound domesticated.

He writes of motivation and he writes about the writing itself, and one of the things that makes his memoir such a good read is that he can actually write very well. Costello has never been lost for words, as anyone who has ever tried to transcribe a few of his lyrics (or those of Bob Dylan, for that matter) will tell you. With the early days out of the way, the second half of the book falls into a sequence of (Dylan again) Chronicles-esque vignettes, leaping from studio to studio, and more pointedly, collaboration to collaboration as the mood hits him. He is, after all, a chronic name-dropper still apparently staggered to realise that he’s either written, recorded, or performed with more or less every (living) idol he ever had, from Chet Baker to Paul McCartney, Solomon Burke to James Burton, and Bacharach of course.

At the same time, there’s a lot he doesn’t discuss—oft-told by others, and lightly reiterated here, his opinion on his on-the-spot (re-)christening at Stiff Records might have been illuminating. Sundry animosities are announced but not addressed; and though he discusses the fall-out from his racist outburst during a petulant drunken row with Stephen Stills, we get a lot less explanation of what really happened than he spends on, for example, the Frank Sinatra show he attended in 1980.

But he does tell us about how he became the unwitting cause of June Carter getting mighty vexed with husband Johnny Cash; about having a row with Joni Mitchell over his ill-advised use of the word “diffident”; and about the time Allen Toussaint asked him to help out with the broccoli. And discovering Elvis’s affection for the Incredible String Band is almost as gratifying as John Lydon’s confession that he loved the first 10cc album. You exit the final page with a new appreciation for what its author has accomplished (not only can the man walk on his ankles, he was once made to do so by a lady who refused to believe he was who he is) and a fresh curiosity for any and all of the albums he’s made that you might have managed to miss.

Like most artists whose careers are now approaching their fiftieth anniversary, Costello has made a few mistakes, a few lousy albums, a few regrettable missteps, and so on and so forth. But he ’fesses up to a lot of them with sometimes coruscating honesty, and he also repeats a misapprehension that, quite possibly, is the most memorable quotation in the book. No, not Frank Capra dismissing modern Hollywood as “a crazy bastardisation of a great art to compete for the patronage of deviants and masturbators” (which could easily be a summation of a lot of other modern art forms as well). And not the unnamed BBC producer who once stopped Costello at an awards ceremony to sternly inform him “you’d have had a lot more hits if you’d just taken out all the sevenths and minor chords.”

No, the best quote belongs to the “local hothead” who buttonholed Costello in an elevator in the Allentown Holiday Inn one day, and announced, “You look like Billy Joel.” Which must have made a welcome change from being told he looks like the guy from Roogalator. Happy birthday, Elvis.