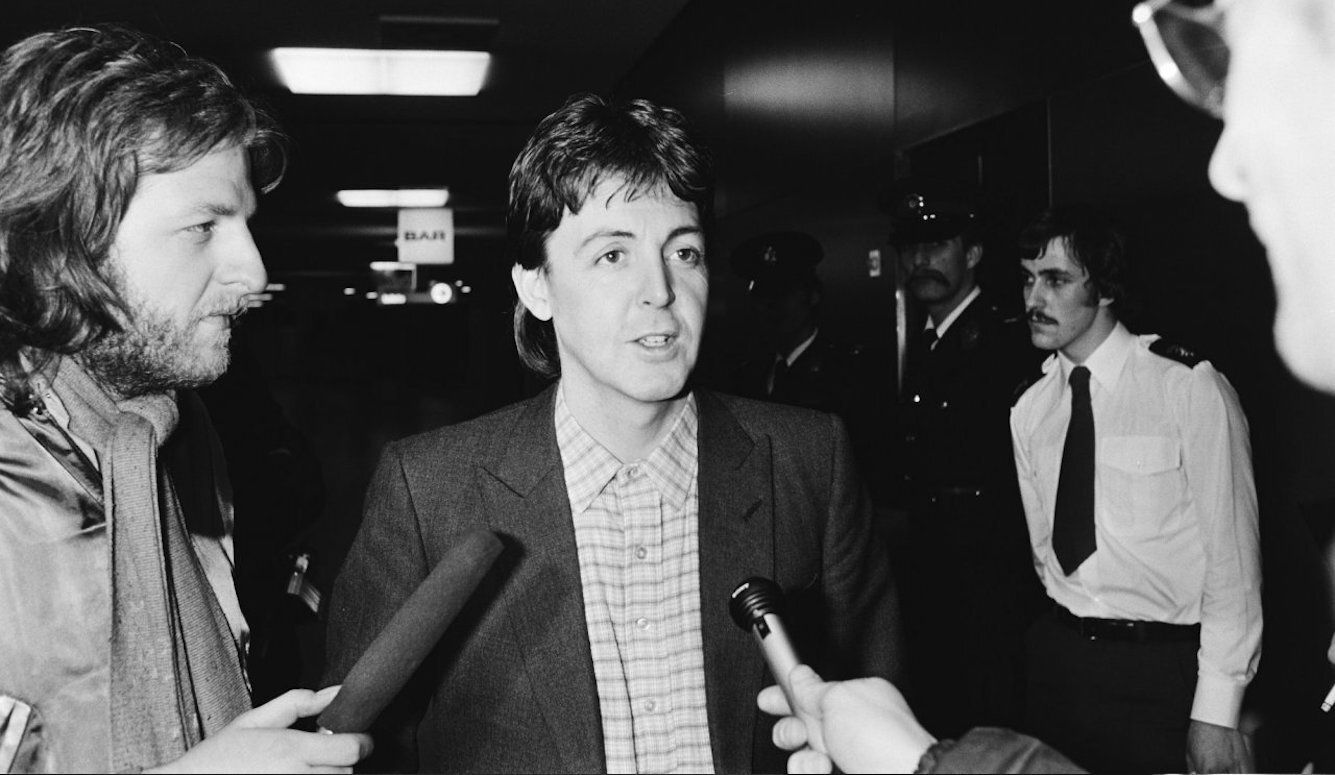

I’m out here putting my feet up and relaxing, trying to pretend that I am just a normal person.

~Paul McCartney, 1981

There is a scene in the 1973 TV special James Paul McCartney in which our eponymous hero is filmed in a pub supping pints and smoking cigarettes with a bunch of scousers who look like they’re in their 70s but were probably only in their 50s. Paul McCartney stands out like a sore thumb, partly because he is still ridiculously good looking, having not aged a day since 1963, but mainly because he’s Paul McCartney, one of the most recognisable people on the planet.

Nothing happens in the scene. He just drinks and chats to his family and joins in a pub singalong like an ordinary bloke. It doesn’t go anywhere. It is in the film because it is Paul’s fantasy. It is not just that McCartney wants to be seen as an ordinary bloke. He wants to be an ordinary bloke. But that can never happen. He couldn’t go into a city centre pub and be treated like one of the boys in 1973 and he can’t do it now. “I know I can't be ordinary, at all—I’m way too famous to be ordinary,” he wrote in his 2021 memoir The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present, “but, for me, that feeling inside, of feeling myself still, is very important.”

Of feeling myself still. This is something he comes back to again and again in his music and interviews. In the last 15 years, he has written three nostalgic songs—‘That Was Me,’ ‘On My Way To Work,’ and ‘Early Days.’ Tellingly, they are all about the time before he was famous. Despite having eight decades of memories to choose from, it is the years when he was ordinary that he keeps harking back to.

“Being ordinary. I love that,” he told GQ in 2020. “It means a lot to me—maybe too much to me.” Few great artists have worn their genius as lightly as Paul McCartney and none has been so committed to being a normie (or what his generation might have called a “square”). He is the only Beatle who regularly returned to Liverpool after they got famous. He sent all his kids to state school. He is mildly obsessed with public transport. He has been known to wear a disguise so he can mingle in crowds. For all we know, he does this all the time.

And by the standards of the music industry, McCartney is a pretty normal person. He seems to have mostly middle-of-the-road opinions, simple tastes, and centrist political views. He is not crazy or self-destructive. A few arrests and deportations notwithstanding, he was always the sensible Beatle. When Lennon accused him of living with “straights” in “How Do You Sleep?,” McCartney said, “So what if I live with straights? I like straights.” Unlike Lennon, who was an unusual man with extraordinary talents, McCartney is an ordinary man with extraordinary talents—and happy to be that way.

McCartney could meet anyone and go anywhere. He could have spent the last 50 years in a gilded cage, as he sometimes has to when on tour, but he doesn’t want to and he has worked hard to avoid it. On Band on the Run, the world of privilege is represented by Mrs Vandebilt whom McCartney tells to go away. As he later explained in The Lyrics:

I don’t want Mrs Vandebilt or her ilk to intrude on my tranquil time. She’s going to spoil it for me. She’s going to make me obey rules that I don’t want to obey. She’s going to pull me up into her cloud of money and influence and authority, and I would rather be spending my time with the Eleanor Rigbys of the world.

Admittedly, McCartney’s desire to live like an ordinary person only goes so far. He has luxury homes all over the world and more money than he could ever spend. His current wife had a net worth of $200 million when he met her in the Hamptons. McCartney has too much talent and ambition to have been happy playing piano in a Liverpool pub all his life. He always wanted to be rich and famous. He understands that the loss of anonymity is part of the deal, but after 60 years it is still a loss he feels keenly. He created the Eleanor Rigbys and the Desmonds and the Mollys as a way of maintaining a connection to the ordinary world, to ground him, as a way of “feeling myself still.”

It is all part of his strategy to stay sane. Normal people have privacy and McCartney does not want the whole world knowing his business. By singing about other people, he avoids singing about himself. He has suggested that even the songs that are about him are not really about him. “Starting with myself, the characters who appear in my songs are imagined,” he says in The Lyrics, “I can’t state that often enough.” Well, yes and no. ‘Dear Boy’ was about Linda’s ex-husband, ‘Hey Jude’ was about Julian Lennon, and ‘Too Many People’ was about John and Yoko. McCartney has said so. And ‘Her Majesty’ was clearly about the Queen. You could argue that these are real people, not characters, but McCartney says “starting with myself.” Is Paul McCartney just another invented character? Does he keep his face in a jar by the door?

Trouble is you expect too much from a man like Paul McCartney. It must be hell living up to the name.

~Melody Maker, 1971

When the Beatles broke up in late 1969, Paul McCartney retreated to his farm in Scotland with his wife Linda and their children. If he had wanted to secure lifelong adoration, he could have stayed there and never released another record. His legend would have only grown. Instead, he set out to do it all again. He never wrote another ‘Blackbird’ or ‘For No One,’ but then who did? It is enough that he formed one of the most successful bands of the 1970s, wrote a string of smash hits, including one of the best James Bond songs and the UK’s best-selling single to date, made at least one classic album, and was still producing high quality work in his 70s. If the Beatles had never existed, Paul McCartney would still be considered one of the greats.

With his preternatural gift for melody, the band’s crowd-pleasing thumb-raiser was always the Beatle most likely to succeed as a solo artist. But, by God, did he make heavy work of it in the early 1970s. It didn’t help that he was blamed for breaking up the best band of all time, or that he had taken his bandmates to the High Court, or that John Lennon had turned the music press against him. His early records are now widely cherished, but they were considered an insult to his fanbase at the time. The first of them, McCartney, was a series of mostly forgettable self-recorded ditties plus the absolute banger ‘Maybe I’m Amazed.’ “I thought it was rubbish,” said Lennon with his usual tact, before adding presciently: “I think he’ll make a better one when he’s frightened into it.”

In May 1971, he—or rather “Paul and Linda McCartney”—released the album Ram. Much beloved of hipsters today, it was panned by critics. The eccentric medley ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’ somehow reached the top of the American charts, but it was not released in the UK where ‘The Back Seat of My Car’ was chosen as the British single. One of McCartney’s greatest post-Beatles tracks, ‘The Back Seat of My Car’ wouldn’t have been out of place on Abbey Road, but the record-buying public were unmoved and it stalled at number 39.

Ram is now considered a lo-fi masterpiece, but don’t be fooled by the homemade cover and rural imagery. It was recorded in New York and Los Angeles, and has high production values when it wants to. McCartney worked hard on at least half of it and had high hopes for the album, but he crammed the best material at the end of each side, leaving the listener to wade through too much lazy filler before they got to the gold.

Nevertheless, it did not deserve the vitriolic reviews it received from the pro-Lennon press which must seem baffling to the modern listener. They certainly surprised McCartney who told Melody Maker in November 1971:

I tried very hard and I really hoped people would like it. I liked it myself and I still do. It was probably a little too important to me to feel that people ought to like my music. I really wanted them to like Ram. I thought I had done a great album. I don’t see how someone can play it and take in all that stuff and turn round and say, “I don’t like it” just like that.

A few weeks before Christmas 1971, his newly formed band Wings—McCartney, his wife, and two blokes who were both improbably called Denny—released Wild Life, a record with so little commercial potential that the record company didn’t bother to release a single from it. Unashamedly ramshackle, with five of its eight songs recorded in one take, it was the final straw for many record-buyers.

Wild Life is actually a pretty good album and rewards repeated listening. If it had been what it pretended to be—a debut album by a bunch of hippies—people would probably have said it was brimming with raw talent. McCartney sings the title track and ‘Dear Friend’ with an unusual degree of emotion and there are some strong songs underneath the lackadaisical production. But Beatles fans were waiting for him to make another Sgt. Pepper. With the benefit of hindsight, we know this was never going to happen and can enjoy his back catalogue without the weight of expectation. But at the time, it seemed like McCartney might be cracking up. Even the usually supportive Ringo Starr said that he “seems to be going strange.”

He was certainly behaving a little erratically. In February 1972, three months after complaining that Lennon was doing “too much political stuff” and having recently recruited an Ulster Protestant, Henry McCullough, into the band, Wings recorded ‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish.’ EMI begged him not to release it as a single because it would be banned by the BBC. He did and it was. Inspired by Bloody Sunday, this surprisingly jaunty protest song wasn’t very good, although it was better than Lennon’s similarly themed ‘The Luck of the Irish,’ released in the same year, which included such lyrical gems as “Let's walk over rainbows like leprechauns/The world would be one big blarney stone.”

McCartney then went to the opposite extreme by releasing ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb,’ an insipid musical reworking of the children’s nursery rhyme, as a single. The final Wings single of 1972 was ‘Hi Hi Hi,’ the first of many underwhelming uptempo pub rockers designed to be played live. It was also banned by the BBC, not because it was about drugs (which it probably was) but because it was about sex. The BBC thought McCartney sang “get you ready for my body gun,” whereas the actual lyrics were, more bafflingly, “get you ready for my polygon.” The BBC had nevertheless got the gist. Other lyrics, such as “I'm gonna do it to you” and “I go like a rabbit,” were less ambiguous.

An artist who had released two banned singles, a nursery rhyme, and three critically reviled albums in a row was not the obvious choice to write the theme song to the new James Bond film and yet, remarkably, that is what he was asked to do. Reunited with George Martin and under pressure to produce something worthy of the franchise, he rose to the challenge (when you got a job to do, you got to do it well). “Live and Let Die” became the catalyst of his commercial rejuvenation.

But first there was the false start of Red Rose Speedway, which Lennon later claimed, improbably, was the last McCartney album he bothered listening to. It went to number one in the USA off the back of ‘My Love,’ a song about his wife that seems to start halfway through, as if he’d written verses and a chorus but decided to just use the bridge. It’s beautiful, but the album was poor. Its original producer, Glyn Johns, left after a few weeks because the band would “sit and play shite and get stoned.” The finished product was bereft of good hooks but it had more polish than Wild Life and prepared the ground for McCartney’s only truly great solo album that was released eight months later.

Band on the Run was recorded in Nigeria where Paul and Linda were mugged at knifepoint and had their demo tapes taken from them. Reduced to a trio after the drummer and guitarist had left the group a few days earlier, Wings appeared to thrive in the adversity and finally produced an album that was all killer and no filler. It went straight to number one in December 1973 and returned to the top spot in July 1974.

By this time, the solo careers of the other Beatles were flagging. Being a former member of the Fabulous Four was no longer enough to guarantee record sales. The kids had moved on. Ringo’s string of top 10 hits had come to an end and he would never again grace the top 40 in Britain. Harrison would never live up to the promise of All Things Must Pass and would soon be in court for “subconscious plagiarism” for the biggest hit on that album (‘My Sweet Lord’). As for Lennon, he released two stone cold classics in Plastic Ono Band and Imagine before moving to New York where he started hanging out with the likes of Tariq Ali and became the kind of person he had ridiculed on ‘Revolution.’ This led to the horrible misstep of Sometime in New York City, a double album of atrocious protest songs and various live recordings which involved more screeching from Yoko Ono than the record-buying public could stomach. (When Frank Zappa released his own mix of one of these tracks in the 1990s, he titled it ‘A Small Eternity with Yoko Ono.’) Lennon returned to form with 1974’s Walls and Bridges LP but within a year he was out of contract and on a five-year sabbatical in the Dakota.

McCartney, meanwhile, just kept powering on. He consolidated Wings’s reputation with Venus and Mars (1975) and Wings at the Speed of Sound (1976). He toured the world with his mullet and his chipmunk grin, enjoyed six more top-10 hits, and released a triple live album that topped the US charts.

When I browsed secondhand record shops in the 1990s, there were always plenty of copies of Venus and Mars available, which suggests that a lot of people bought it at the time but later realised they could live without it. And it is true that McCartney never made an album quite as good as Band on the Run again.

For the next 25 years, his career was characterised by a lot of solid forward defensive shots, occasionally smacking one out of the park and sometimes knocking his own stumps over. Nearly every Wings LP consists of two or three absolute belters and a lot of filler, with the quality of the overall product depending on whether the filler was half-decent or poor. Almost everything on Red Rose Speedway apart from ‘My Love’ is forgettable. Venus and Mars has ‘You Gave Me the Answer,’ ‘Call Me Back Again,’ and ‘Listen to What the Man Said.’ The rest is a mixed bag. Wings at the Speed of Sound is perfectly listenable ’70s soft rock but only transcends the humdrum on ‘Let ‘Em In’ and ‘Silly Love Songs.’

The problem was that McCartney leaned heavily on his faculty for melody, and when that wasn’t productive he rarely had the emotional depth to salvage a so-so tune with powerful lyrics. Lennon’s catalogue revolved around autobiography, McCartney’s around fiction. When Macca writes a song, he wants to sing it, and that requires lyrics. But since leaving the Beatles he has always had more tunes than he has had things to say. McCartney was obviously right when he said (in The Lyrics) that “some of my songs have functions above and beyond merely getting themselves into the world.” But not all of them, or even most of them, and when McCartney has nothing to say, he throws lines together almost at random or makes up little stories. “If you think about it, the vignette is really my stock-in-trade,” he says. Peter Jackson’s recent Get Back documentary shows his process in real time. As we watch him creating the song ‘Get Back,’ he comes up with two wafer-thin characters—“Jo Jo” and “Sweet Loretta Martin”—and casts around for words that sound nice together.

Putting vignettes to music is all well and good when your melody is as strong as that of ‘Get Back,’ or if your story is as evocative as that of ‘She’s Leaving Home,’ but not so much when the tune sounds like a Status Quo B-side, such as ‘Girls’ School’ or ‘Soily.’ In The Lyrics, McCartney said of his 1975 album track ‘Spirits of Ancient Egypt’: “I had this belief that you could throw words together and they would attain some meaning, that you didn’t need to think it out too much.” You can get away with putting a nonsense verse over a tune like ‘Jet,’ but all too often in the 1970s, McCartney was putting it over the likes of, well, ‘Spirits of Ancient Egypt.’

Plucking words out of the ether and expecting to find meaning in them is the classic ‘60s stoner approach to songwriting. The Beatles had been at the forefront of this with songs like ‘I am the Walrus’ and ‘Come Together,’ but Lennon abandoned it in 1970 and swung in completely the opposite direction for the rest of his life. McCartney, on the other hand, continued to employ this technique and his prodigious use of cannabis should probably not be overlooked in all of this. It is easy to forget that McCartney has been devoutly attached to marijuana for most of his adult life. He was busted for growing it on his farm in Scotland in March 1973, only a few months after being fined for possession in Sweden. He was busted in Los Angeles in 1975 when police found cannabis in his car and, most famously, was imprisoned in Japan for 10 days in 1980 when eight ounces of cannabis was found in his suitcase. Upon release, he told reporters, “I have been a fool. … From now on, all I’m going to smoke is straightforward fags and no more pot!”

But, dear reader, he did keep smoking pot. He was busted in Barbados in 1984 after buying marijuana on the beach and Linda was busted eight days later trying to bring it through Heathrow Airport. He only gave up smoking weed at the ripe old age of 69, long after he had quit “straightforward fags.” And why not? you may ask. It didn’t stop him working and it may have given him some inspiration. Alas, weed’s ability to give artists wild and original ideas is greatly exaggerated. It is more likely to breed complacency. Surrounded by yes men in a haze of THC, quality control took a back seat. Of McCartney's solo career, Taylor Parkes wrote that “those first ten solo albums contain the most unmistakably pot-inspired music ever committed to posterity. Not because they’re spaced-out, or laid-back. They reflect the reality of the everyday toker: lazy, whimsical, totally unfocussed, brimming with bright ideas, which buzz around for a moment or two before vanishing like burning paper.”

But the shallowness and frivolity of much of Wings’s material didn’t really matter in 1976. McCartney was no longer competing with John Lennon, and the pop music business put little stock in emotional depth. When ‘Silly Love Songs’ was released on April 30th, 1976, the number one spot was held by the Brotherhood of Man with ‘Save Your Kisses For Me’ and ABBA were at number two with ‘Fernando.’ Many of the acts in the top 20 that week only exist today as answers to questions in a particularly difficult pub quiz, including Hank Mizell, Fox, Sailor, Silver Connection, John Miles, Sheer Elegance, Laurie Lingo and the Dipsticks, and the Andrea True Connection. ‘Silly Love Songs’ was high art compared to this kind of stuff. Indeed it was high art. The melody is joyous, the arrangement first rate, and the lyrics wonderfully defiant. But it was still kept off the number one spot by The Wurzels’s novelty track ‘The Combine Harvester.’

If some of McCartney’s music from the era sounds dated now it is because it sounded contemporary at the time. He leant into the ’70s in a way that Lennon, who never fully extracted himself from the late ’60s, never did. McCartney did not just adapt to the decade, he helped make it what it was. What could be more ’70s than a triple live album by Wings (Wings Over America)? What could be more ’70s than ‘Mull of Kintyre’ which stayed at number one for nine weeks and was not just the best-selling single of the decade in Britain, but the best-selling non-charity single of all time? (It was later beaten by Band Aid’s ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas,’ which McCartney sang on, the reissued ‘Bohemian Rhapsody,’ and Elton John’s 1997 tribute to the Princess of Hearts.)

‘Mull of Kintyre’ was a phenomenon. I’m not saying it was the greatest song McCartney ever wrote, or even that I particularly enjoy listening to it, but it once again demonstrated his uncanny ability to create something timeless from the most basic raw ingredients. He had never tried writing a folk song before and he would never bother again. He casually nailed it first time and stuck it out in 1977, the year of punk, where it beat all comers.

‘Mull of Kintyre’ consists of three simple chords played in a way that someone who has just started learning the guitar would play them. It seems incredible that the song had not been written before. When McCartney came up with the melody to ‘Yesterday’ in his sleep(!), he famously believed it to be an old tune and played it to friends for a year until he received enough blank looks to be convinced that it was his. One wonders if he did the same with ‘Mull of Kintyre.’ Even without the bagpipes adding to the traditional feel, it sounds like it has been around forever.

By the end of the 1970s, Paul McCartney had done it all again. He’d had smash hit after smash hit and reconquered America. Everything had gone to plan. In August 1972, when Wings were playing small university gigs, he’d said: “You want to try a whole new thing, so that you say ‘Well, this is me.’ Then you do the Beatle stuff once you’ve established yourself.” Mission accomplished, a few Beatles songs were added to the set list of the 1975–76 world tour. When he toured the world again in 1989–90, half the songs were from the Beatles era.

But first he had to navigate the 1980s. By 1979, he was getting bored with the ever-changing line up of Wings and recorded his second official solo album, McCartney II, which veered between the sublime and the ridiculous, was hated by the critics, and has since been rediscovered by millennials, some of whom hold it in high regard. I find it largely unlistenable myself but, as usual with a Macca album, it contained one classic (‘Coming Up’).

Your life will not be significantly worse if you never hear Tug of War, Pipes of Peace, or Press to Play. The last of these is the worst album of his career, characterised by the two things that often held him back: epic cannabis consumption and a refusal to take constructive criticism. Some of the tracks from these records, such as ‘What’s That You’re Doing?’ and ‘Footprints,’ are not bad. Not bad, but as they say of Lou Reed’s solo career in Trainspotting, “in your heart, you kind of know that although it sounds alright, it’s actually just shite.” McCartney retained his ability to write a catchy hit single, but his powers were waning.

After the death of Lennon in December 1980, Paul was unfairly portrayed as the lightweight of the songwriting partnership. He fiercely defended himself from this charge in interviews while undermining his case by releasing some of the most pedestrian music of this career. He ended the 1970s with the godawful ‘Wonderful Christmastime,’ a song that sounds like something he knocked off, half-cut, after the Queen’s speech with a cheap Casio keyboard that the kids had bought him as a present. His 1982 album Tug of War received better-than-average reviews but, aside from his tribute to John Lennon (‘Here Today’), it was insubstantial. The title track is a sort of protest song that has no idea what it is protesting against (“It’s a tug of war/With one thing or another”). On ‘The Pound is Sinking’ we find him singing about international current markets for some reason. (“The dollar's moving, the ruble's rising/The yen is keeping up, which hardly seems surprising.” So true.) The album finishes with his well-meaning but much-derided smash hit ‘Ebony and Ivory,’ another McCartney song that walked the fine line between catchy and irritating and was criticised for being simplistic by the same people who idolised the author of ‘All You Need is Love‘ and ‘Imagine.’

In 1984, he released his animated musical of Rupert the Bear, a labour of love which—incredibly—he had been working on since 1970. It yielded the single ‘We All Stand Together,’ a perfectly nice song in the context of a children’s film but further ammunition for the “Paul’s gone soft” faction. The film was released at the same time as his infamous vanity project Give My Regards to Broad Street, a colossal flop which did at least bring forth another classic single in ‘No More Lonely Nights.’

But then, in 1989, we got Flowers in the Dirt, the closest a McCartney album had come to greatness since Band on the Run. The second half of the album flags a little, but the whole of the first side is top class, including the duet with Elvis Costello—‘You Want Her Too’—which is a grittier version of ‘The Girl is Mine.’ 1993’s Off the Ground was a more forgettable affair, best remembered by Beatles fans for the pointless wordplay of ‘Biker Like an Icon,’ a song which, Wikipedia notes brutally, “reached number 62 in Germany”.

But it didn’t really matter because McCartney was about the enter his elder statesman period.

I mean, one good thing is that I care. I’m not just putting out bullshit all the time. I am trying to do good stuff. Maybe you can’t succeed all the time, but I love it.

~Paul McCartney, 2020

Paul McCartney was knighted in March 1997. The album he released two months later, Flaming Pie, marked the start of his critical rejuvenation. I never really understood what all the fuss was about and I still don’t. Flaming Pie had enough echoes of the past to satisfy Beatles fans and McCartney sounded more at ease than he had in years, but his long-standing quality control issues were not helped by the rise of compact discs—the album is much too long at 54 minutes. It sounded contemporary but only because a lot of people in the mid-’90s were making music in the same middle-of-the-road style. ‘The World Tonight,’ in particular, sounds like it could have been performed by Paul Weller on TFI Friday.

Nevertheless, Flaming Pie laid the foundations for McCartney’s living legend era. Over the next 25 years, Sir Thumbsaloft would release a further six albums of new material alongside various classical and experimental projects. 2005’s Chaos and Creation in the Backyard marked the start of a purple patch of four consecutive high quality records made for no other reason than a love of making music and with barely a duff song among them. Some of his late-period material is easier to admire than to love, but McCartney was still capable of creating ear-worms like ‘Queenie Eye,’ ‘Happy With You,’ ‘Jenny Wren,’ and ‘Ever Present Past.’ There’s not much to choose between the four records, but the pick of the bunch has to be 2018’s Egypt Station, an album made by a 75 year old grandfather that stands up with the best of his solo work. His 2020 lockdown album, McCartney III, was not in the same class but it got rave reviews anyway because by then the critics were just glad to have him around.

That McCartney made a whole album in lockdown without referring to either the lockdown or COVID-19 in any of the songs is typical of the man. Late-period songs like ‘I Don’t Know’ and ‘The End of the End’ occasionally find him baring his soul, but introspection has never been his thing. A naturally optimistic man, he would sooner search for solutions than dwell on his problems. Like Lennon, McCartney lost his mother in his teenage years but he never wrote a song like ‘Mother’ or ‘My Mummy’s Dead.’ He didn’t write a song about the death of his first wife, nor about his divorce from his second. “John could show how human he was by vocalising all that,” he said in 1982. “It’s just my character not to vocalise that kind of stuff.” He keeps his own counsel. Anytime he feels the pain, he refrains.

His late-period masterpiece ‘Riding to Vanity Fair’ was widely interpreted as being about the Geordie fantasist to whom he was then married. McCartney insists that it is actually about someone else, but won’t say who. It is nevertheless revealing for its opening lines:

I bit my tongue/I never talked too much/I tried to be so strong,

I did my best/I used the gentle touch/I've done it for so long.

Paul McCartney has been one of the most famous men in the world for nearly 60 years. In all that time, he has never lost the glint in his eye that tells us he knows a thousand times more than he will ever say. All the Beatles were tough nuts and McCartney definitely has an edge to him, albeit one only rarely glimpsed by the outside world. One such instance occurred in 2003, when McCartney turned up in central London after midnight to watch the showman David Blaine, whose latest stunt was spending 44 days suspended in a Perspex box by the River Thames with no food. When a newspaper photographer approached him for a picture, he replied: “Fuck off! I’ve come to see this stupid cunt and you are not going to take a picture of me tonight.” McCartney, who may have been the worse for drink, then told a fan to “fuck off” and sacked his longstanding PR man, Geoff Baker, for tipping off the press about his visit.

It's hardly surprising that the congenial public persona cracked occasionally. McCartney has had to grin and bear it when journalists ask him the same tedious questions. In the 1960s, it was “when’s the bubble going to burst?” In the 1970s, it was “when are the Beatles getting back together?” After 1980, it was variations on “what was John Lennon like?” He has tolerated unfair album reviews and cruel comments about Linda. He has put up with Lennon being mythologised at his own expense. He has dealt with all this by talking a lot and saying little. He is happy to tell the same old stories about the Beatles. He is happy to talk about songwriting. But he takes his privacy seriously and has gone to great lengths to build a fortress in which his family can have a life of quasi-normality.

Paul McCartney never claimed to be the voice of a generation. He never portrayed himself as a rebel. He is, at heart, a song and dance man. Out of John, Paul, George, and Ringo, Paul is the only one who would have had a career in music if Elvis had never come along. At the age of 14, he wrote ‘When I’m 64’ because, as he later explained, rock and roll didn’t exist and it was the kind of song that might sell. He could imagine Sinatra covering it. Children’s songs, music hall, Scottish folk ballads, heavy rock, gospel, ragtime. It’s all grist to the mill of the supreme tunesmith.

So long as he has breath in his body he will release more albums, but the music business is no longer about albums. It is about streaming and playlists and stadium shows by “heritage” acts. Paul McCartney is made for this. His stage show is a Beatles jukebox and it only requires some judicious pruning on Spotify to make his post-Beatles back catalogue seem magnificent.

And now this extraordinary man with a thirst for the ordinary is 80 years old and preparing to headline Glastonbury. He doesn’t need the money and he doesn’t owe us anything. Paul McCartney had made enough of a contribution to popular culture by 1965 to justify never working again. How lucky we are to still have him around.

A selection of the author’s favourite McCartney solo tracks that were never hits:

‘Long Haired Lady’ and ‘The Back Seat of My Car’ from Ram (1971); ‘Wild Life,’ ‘Some People Never Know,’ and ‘Dear Friend’ from Wild Life (1971); ‘Nineteen Hundred and Eighty Five,’ ‘Let Me Roll It,’ and ‘Bluebird’ from Band on the Run (1973); ‘Treat Her Gently - Lonely Old People,’ ‘You Gave Me the Answer,’ and ‘Call Me Back Again’ from Venus and Mars (1975); ‘Arrow Through Me’ from Back to the Egg (1979); ‘Blue Sway’ (with Richard Niles Orchestration) from McCartney II (orig. 1980, 2011 reissue); ‘We Got Married’ and ‘You Want Her Too’ from Flowers in the Dirt (1989); ‘Heather’ and ‘From a Lover to a Friend’ from Driving Rain (2001); ‘Riding to Vanity Fair’ from Chaos and Creation in the Backyard (2005); ‘Happy With You’ and ‘Despite Repeated Warnings’ from Egypt Station (2018).