Politics

A Question of Legitimacy

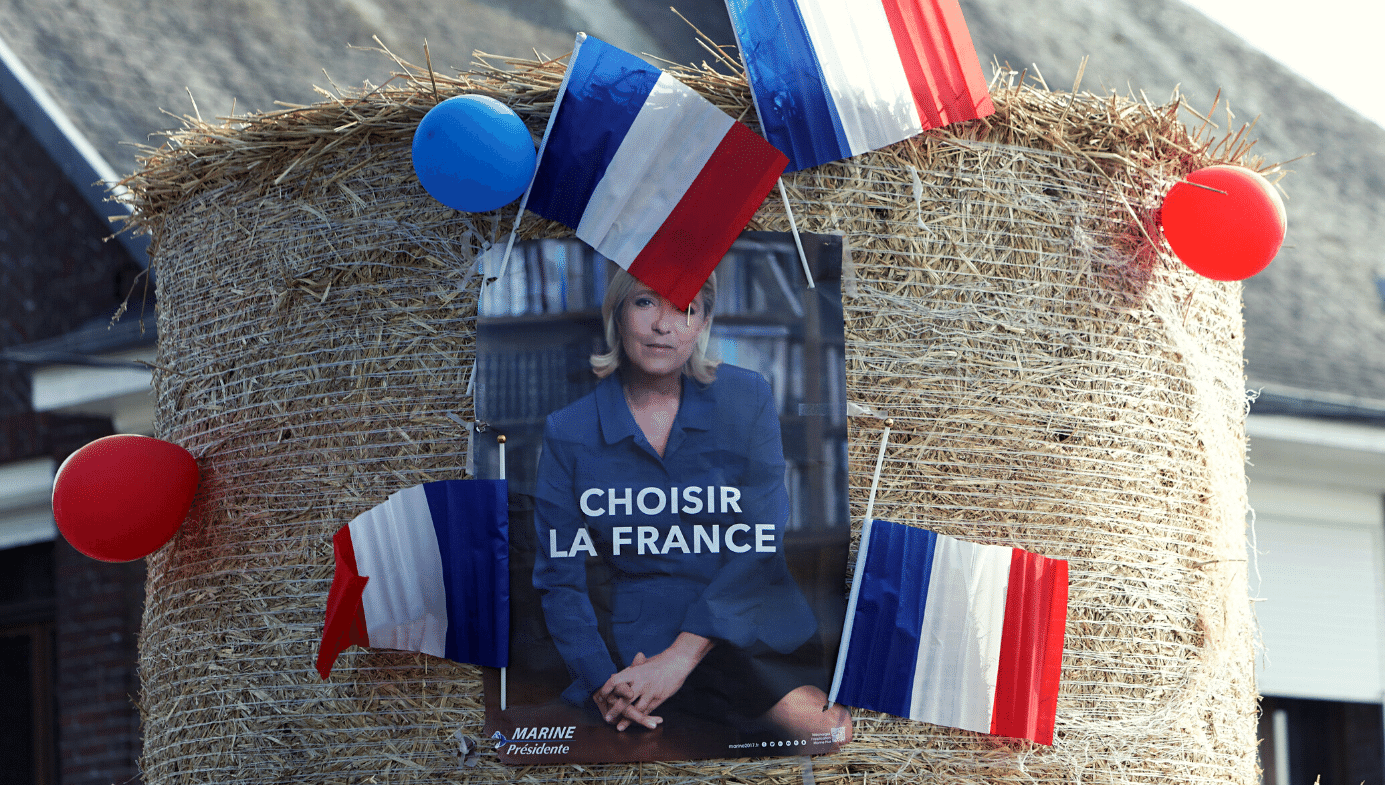

The Rassemblement National was thwarted by a coalition of convenience, but it remains the party with the largest grip on French voters.

On 9 June, French president Emmanuel Macron announced that he was dissolving his country’s National Assembly and that the two-round parliamentary elections would be held on 30 June and 7 July, respectively. The decision to call a snap election was a high-stakes gamble intended to face down Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s New Right party, Rassemblement National, after it humiliated Macron’s centrist Renaissance party in elections for the European parliament. After the first round, that gamble looked to have failed. RN came top with 33.2 percent of the vote, followed by the left-wing coalition, the New Popular Front, which won 28.1 percent. Renaissance (and its allies) trailed with 21 percent. It looked like Macron would be forced to share power with the RN, a party that French liberals and leftists believe—or, at least, say they believe—represents a reincarnation of 20th-century European fascism.

This could not be tolerated. In the second round, those who viewed a resurgent RN with greatest detestation came together to save France from the horror of a parliament dominated by the New Right. That demanded some previously unthinkable political manoeuvres. Édouard Philippe—the first of several prime ministers to serve under Macron, and now the centre-right mayor of Le Havre—worked hard to make a communist the port city’s member of parliament, and all of the non-RN voters in Le Havre got behind him. Thwarting the RN was, Philippe said, a “democratic imperative.” This kind of tactical voting was widespread—socialists voted for liberals, and centrists voted for Greens, conservatives, and occasionally communists to deny 28-year-old Bardella the post of prime minister.

Naturally, Bardella and Le Pen were furious. According to protocol, the president chooses a prime minister from the party or alliance that has won a majority in the Assembly. The RN leadership believed that their vote would produce that majority without any assistance from other parties, and that Macron would therefore have to appoint Bardella. That would have been a further humiliation for the French president after the RN had consigned his party to third place in the first round. But the second round reversed the result of the first, and gave Renaissance the second-most deputies behind the left-wing coalition. The RN dropped into third place.

The two groups now dominant in the Assembly have anxiously watched the RN’s support grow despite their warnings to voters that Le Pen and Bardella are dangerous extremists. The rise in the RN’s popularity has seen France lead a rightward trend in many European states. For a while, the party attracted many more men than women, but it is now seeing the number of women outpace men, many of whom would have scorned the party as extreme in previous years. This broadening appeal is due, in different ways, to the RN’s two leaders.

Marine Le Pen grew up in the family compound paid for by supporters of her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, a former paratrooper who had fought in Algiers and Indochina. Jean-Marie Le Pen founded the Front National in 1972 as a vehicle for his political obsessions—the reintroduction of capital punishment, an end to immigration, and a thoroughgoing dislike of Jews and blacks (especially black players in the national football team). During the 1970s, he was given a 30 million franc fortune by an admirer, along with a mansion and a small park in Saint Cloud on the outskirts of Paris. There, he and his wife raised a family of three girls, the youngest of whom was Marine. (Le Pen’s wife left him and then posed naked for Playboy, an act of revenge that led Marine to break all contact with her mother for 15 years.)

Marine trained as a lawyer and then became her father’s assistant before taking control of the Front National in 2011 and distancing herself from many of his most rebarbative statements and positions. From the beginning of her leadership, she proclaimed that she wished to “shape the Front National as the centre of a grouping of all the French people.” But she did not immediately emerge from the far-right milieu in which she had been brought up. Figures like the historian Dominique Venner, who had been a neo-fascist in his younger years, were valuable mentors. When Venner shot himself in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in May 2013 to protest “the total replacement of [the population of] France, and all of Europe,” she described his suicide as the act of a “broken man” desperate to awaken the French to the parlous state of their nation. She held extremist romantics like him in awe, but she was not of their stamp.

Marine Le Pen’s leadership of the Front National began under the supervision of her domineering father. He continued to express his boundless hatred of liberals and Jews while she tried to inch the party away from his influence. Only in August 2015, after he dismissed the Holocaust as a “detail” of the Second World War, did she move decisively against him, expelling him from the party he had founded and announcing that he did not speak for her. Thereafter, the process of “de-diabolising” the FN brand became easier. With every subsequent run for the presidency after 2012, she steadily increased her vote share, and in 2018, she renamed the party Rassemblement National (“National Rally”). In 2022, she won 41.5 percent of the vote for president against Macron, and in January of this year, she was named the most popular politician in France by Figaro magazine. She is now accepted, if not necessarily admired, by half of French voters—a standing affront to Macron’s determination to end extremism on the Left and Right.

The second agent of change is Jordan Bardella, who has been president of the RN since 2022. Bardella was born into a family of mainly Italian origin and brought up in a broken home in a working-class area of Seine-Saint Denis, north-east of Paris. He is keenly intelligent, but he dropped out of the University of Sorbonne to pursue a political career in the RN, rising to become chairman of the Seine-Saint-Denis chapter while he was still in his teens. He was then taken into the party’s central headquarters to be groomed for leadership. In 2022, having worked stints as party spokesman and then vice-president, Le Pen made way for him to succeed her as the party’s president at the age of just 27.

Bardella is one of the most remarkable new political talents in Europe. Tall and handsome, he projects RN’s stern policies on illegal immigration, Islamic extremism, and security with a charming smile and a fluent oratorical style: “This new, smiling face,” wrote Franck Johannes in Le Monde, “knows very well how to put the finishing touches on the de-diabolisation project of the far-right ... courteous, lively, smiling, and witty when he wishes to be, always carefully turned out, perfectly at ease on TV, and unquestionably brimming with talent.” Even political rivals like Valérie Pécresse of the Républicains say, “He is intelligent, brilliant, he has a real career in politics. That makes him rather romantic.” But, she warns, “he has areas of shadow, more dark than clear.”

After the first-round results in June, Le Pen and Bardella celebrated their imminent arrival in government after decades of carefully striving for acceptance. Amid the jubilation, Bardella began to map out the approaches he would bring to bear when he became prime minister. These plans may have lacked detail, but they were certainly ambitious—he would cut the French contribution to the EU by €3 billion in order to fund tax cuts at home; he pledged to slash VAT on electricity, fuel, and other energy products from 20 to 5.5 percent, and suspend it entirely for scores of basic necessities (to the horror of economists, who pointed to the burgeoning debt); he said he would ban anyone holding dual citizenship from “strategic positions” in the French state (possibly putting the mayor of Paris, Anna Hidalgo, at risk of resignation, since she has Spanish and French citizenship); and he vowed to “preserve French civilisation” with “specific legislation targeting Islamist ideologies.”

Before the election, Bardella and Le Pen both inveighed against the EU’s right to determine national policy. In March, when they launched their party’s successful campaign for the June European elections in Marseilles, I heard both leaders proclaim France’s independence from Brussels. French law, they argued, must trump European law in any contest—a direct challenge to the EU’s primacy. Unsurprisingly, Brussels does not want to see a RN government in France.