Politics

A Fracture Revealed, Not Healed

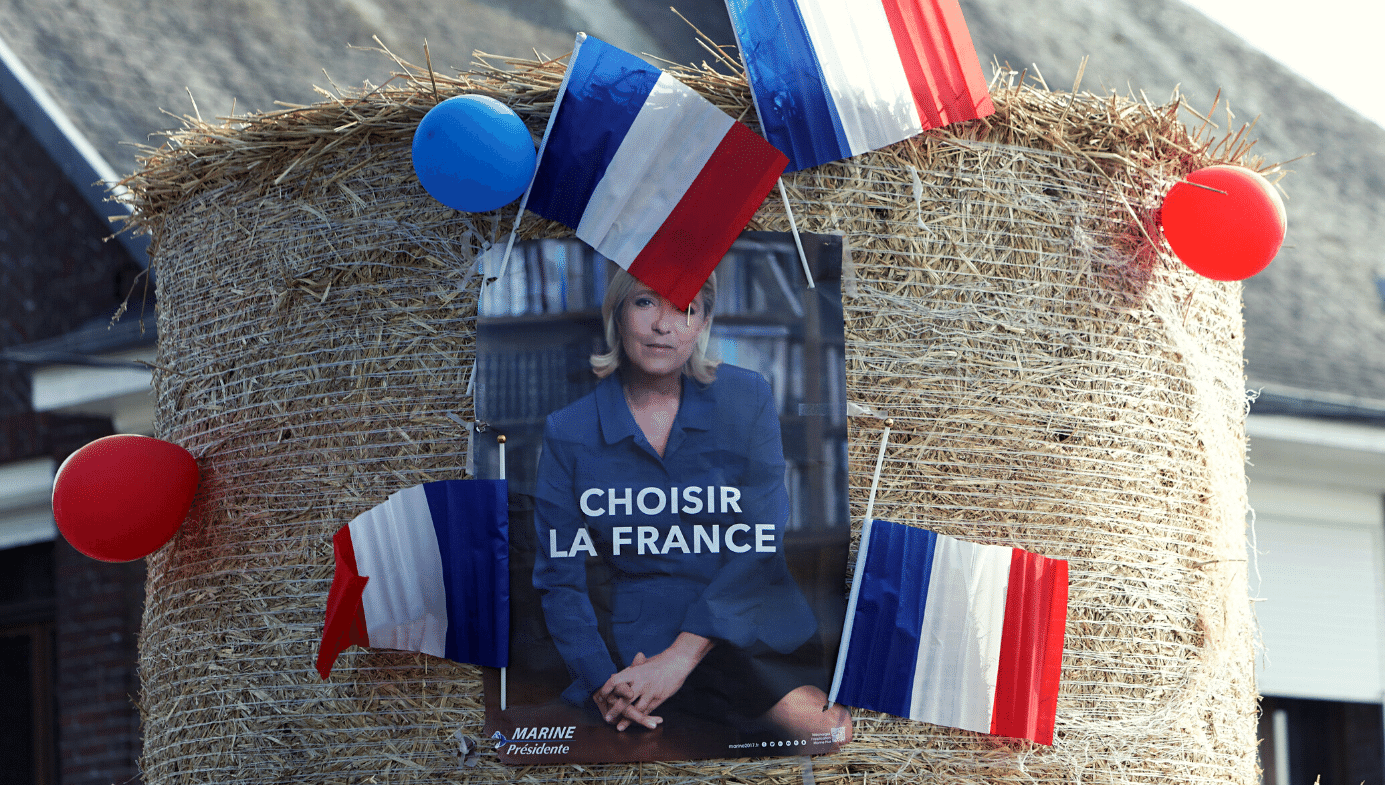

As the scale of her defeat in the Presidential election was announced, Marine Le Pen, leader of the Rassemblement National (RN), was quick to gloss it. “Millions of our compatriots,” she declared (in a speech that must have been prepared for weeks), “have chosen the national camp and change,” and the result, she assured them, “represents in itself a great victory.”

The key phrase here is “in itself” (“en lui-même”). For outside of itself, the result was an unambiguously heavy defeat: Emmanuel Macron received more than 58 percent of the national vote and became president of France for another five-year term (an unusual victory for a French president, in a country which tends to dismiss them after just one).

This is a margin which, in any other contest anywhere, would make Le Pen’s boast of “a great victory” (“éclatante victoire”) look absurd or positively unhinged. But “in itself,” the election has provided a sobering snapshot of a liberal centre savaged by her party’s relentless progress, and by the inroads made by other populists. The truth or inaccuracy of her claim will, in the succeeding months and years, be the framework within which French politics must operate.

The growth of the RN has been steady over two decades. Jean-Marie Le Pen, a former paratrooper, raised the banner of the Front National (FN) 50 years ago—a grouping which attracted first thousands, then millions of votes, but failed to win him a place in the final presidential run-off. Until 20 years ago, that is, when he qualified to fight the centre-Right politician and former Mayor of Paris, Jacques Chirac, in the second round of France’s two-stage election process. Le Pen lost that encounter heavily, securing a meagre 18 percent of the vote, and Chirac’s winning total of 82 percent was the largest recorded in presidential tournaments.

After failing to qualify for the second round in the election of 2007, the 78-year-old patriarch stood aside, and FN members elected his daughter Marine to the party leadership. She fought the 2012 presidential election but did scarcely better, obtaining just under 20 percent in the first round—nearly six and a half million votes—and in the run-off, the socialist François Hollande unseated the centre-Right incumbent, Nicolas Sarkozy.

The real breakthrough arrived in 2017, when Le Pen took her party into the second round once again, only to fall before the wave of support for a wholly new contender, Emmanuel Macron and his En Marche movement. This time, she recorded a vote of just under 34 percent (10.8m votes) against Macron’s slightly more than 66 percent (20.7m)—almost double Le Pen’s score.

That gulf has now been significantly reduced: 58.55 to 41.45 percent is comfortable, until one makes the less comfortable observation that the latter are not just citizens with different political views from the former, but a different kind of constituency entirely. In a column published just after Macron’s second win, the American journalist Christopher Caldwell remarked:

… increasingly, the elite and the non-elite political tendencies have no more contact with one another than if they were living on isolated islands. Macron is the candidate of rich cities, beach towns, ski resorts and the “instagrammable” parts of France.

But 60 kilometres outside of France’s cities, Marine is the most popular politician. She is the candidate, writes [political scientist Jérôme] Fourquet, of people whose work involves repetitive tasks, bad smells, irregular hours and loud noises. In the very richest neighbourhoods, though, it is as if she doesn’t exist. In the first round in the 6th arrondissement of Paris (the one that contains St-Germain-des-Près and all those cafés Hemingway drank in), she got 4% of the vote and finished sixth. Just 854 people ticked her box.

The anti-establishment anger from which Le Pen has benefitted was demonstrated most vividly during 2018–19 by the Yellow Vests (Gilets Jaunes) movement. Never fully revolutionary, nor able to penetrate the heart of governance as the MAGA movement did in January 2021, the Yellow Vests nevertheless swelled to some three million militants.

Overwhelmingly comprised of working- and lower-middle-class people from outside the big cities, the movement was ostensibly a vehicle formed to express specific gripes about policy, such as the hike in petrol and diesel prices and the stagnation of wages. But it also expressed an overpowering feeling of neglect and disrespect—when noticed at all, its grievances were routinely dismissed as the product of resentful racism, an accusation which has only inflamed the sense of victimhood and the concomitant demands for recognition.

As the British writer and Paris resident Gavin Mortimer has observed:

… there may well be among them a minority who hold views similar to those of Le Pen’s bigoted father, but the majority are not racists or reactionaries; they are hard-working men and women who for too long have felt disrespected and neglected by a wealthy political and cultural elite. Their arrogance, their entitlement and their startling absence of empathy have angered and alienated great swathes of the country, especially the 14.6 per cent (9.2 million people) who live below the poverty line, an increase of half a percent since the year Macron took office.

Mortimer’s mention of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s bigotry illuminates a crucial fact. Le Pen’s distaste for Jews—and his contemptible dismissal of the Holocaust as “a detail in the history of World War II,” in particular—meant that his appeal could never extend far beyond a following which was itself racist, or prepared to tolerate racism in its leaders.

His daughter, however, has made that break fairly convincingly—she expelled her father from the FN, her former partner of 10 years (until 2019) is part-Jewish, and she has renamed and rebranded the family party. And while many dispute that antisemitism has been wholly purged from the party faithful, it is now banned in public in any form. This “detoxification” process, which Marine Le Pen began and then accelerated over the past two decades, seems to have worked: she is still not accepted into the ranks of “normal politics” by the dwindling number of those voting centre-left or centre-right, but her reforms have been enough to attract much wider communities of support.

This seems to have made the difference to how her party is perceived and to how the French electorate choose their political leaders. In the 2022 presidential race, the Republicans on the centre-Right and the Socialists on the centre-Left—until the turn of the century, the two “traditional” parties—were both reduced to single-figure support. These establishment parties have been replaced by the Rassemblement National on the far-Right, En Marche in the technocratic centre, and France Insoumise (France Unbowed) on the far-Left led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon. In the first round of the race, Mélenchon scored 22 percent of the vote, just short of Le Pen’s 23 percent—an indication that with one more heave, the leftist might have faced the centrist in the run-off.

In France and Italy (and, to a lesser degree, in Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden), right-wing populist parties have entered politics in a commanding way. None has so far achieved the electoral success of Le Pen or the two Italian far-right parties, Lega and the Fratelli d’Italia, but while their support waxes and wanes a bit, it never sinks to low single figures. In the former Communist states in Central Europe, the ruling parties in Hungary (Fidesz) and Poland (Law and Justice) remain on the far-Right of politics and increasingly seek alliances with other likeminded European parties.

Many of these leaders have been embarrassed by their admiration for Russia and for its president, Vladimir Putin, but all (with the exception of Fidesz) have hastily backtracked, and condemned the invasion of Ukraine. As a result, there is only limited evidence that the pro-Russian stance has seriously affected them. Their robust health is partly explained by their opposition to mass—and in some cases all (apart from Ukrainian)—immigration, and by their hostility to Muslim immigration in particular. These shared attitudes are still largely taboo on the liberal centre and the Left, though there is an increasing number of exceptions, including in the rhetoric and policies of Macron before the election.

However, right-wing populists have also adopted economic and social positions shared, in whole or in part, by other political movements on the centre and the Left. One of these is Euroscepticism, a current which continues to gather strength and momentum. Brexit has been the most dramatic instance of this trend, but while disappointed British Remainers make sporadic efforts to frame Leavers as racist and/or stupid, the ruling Conservative Party leadership is not of the far-Right. Nevertheless, every party of the European far-Right is Eurosceptic to some degree.

Le Pen is highly suspicious of Brussels, committed to leaving the euro currency area and even the Union itself, and determined to repatriate political power to Paris. In a pre-election interview with the UK’s Daily Express, she revealed that her party had signed an agreement with 15 other parties to cut the EU’s powers and scope. “The EU,” this joint declaration claims, “is becoming more and more a tool of radical forces that would like to carry out a cultural, religious transformation and ultimately a nationless construction of Europe, aiming to create … a European Superstate. European nations should be based on tradition, respect for the culture and history of European states, respect for Europe’s Judeo-Christian heritage and the common values that unite our nations.”

This document articulates many of the European far-Right’s central concerns—fears of a “European superstate” and the threat to national cohesion posed by “globalisation” are said to be the cause of the vast chasm between elites and the majority. The dangers they pose to the working and lower-middle classes of Europe have prompted resistance from the lower classes for more than two decades, and that resistance has grown. It is now shared and approved of by movements of the Left and centre.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon is even more explicitly anti-globalisation than Le Pen, and this seems to explain, at least in part, his late surge in the presidential polls. In the week before the election, Marc Glendening of London’s Policy Exchange think tank wrote that “a fascinating aspect of this extraordinary race is the way in which economic globalisation, and the associated issue of immigration, is now becoming the axis around which politics is re-aligning. The traditional mass bases of support for the mainstream centre-left and centre-right parties are fracturing along this fault line.” In his writings, speeches, and interviews, the celebrated French economist, Thomas Piketty, has also affirmed that globalisation is at the root of rising inequality, though his recipe for dealing with it remains vague.

Still deeper within the global elite, the popular American philosopher Michael Sandel has used his 2020 book The Tyranny of Merit to argue that “at a time when anger against elites has brought democracy to the brink, the question of merit takes on a special urgency. We need to ask whether the solution to our fractious politics is to live more faithfully by the principle of merit, or to seek a common good beyond the sorting and the striving.”

This argument runs against the dominant view of those who have benefitted from globalisation, and the post-liberal movement now gaining strength in the US and the UK has embraced this line with enthusiasm. The consequent reshuffling of political allegiances has blurred traditional party lines. Far-Right parties have seized the opportunity offered by a new strand of illiberal politics not confined to their rebarbative nativism, and they have marched into what was once left-wing territory evacuated by a centre-Left that discarded socialism for neoliberalism in the late 1990s.

This does not mean that those groups and movements on the further reaches of the Left and Right will necessarily unite or agree upon common platforms: for now, there remains too much disagreement on issues of identity, immigration, and (in some cases) the EU for that. It does mean, however, that the claim staked by figures like Le Pen on lower-class support has been strengthened, and that a reassessment of what constitutes the political “Left” and “Right” is now well under way.