Politics

Sin and Social Science

Glenn Loury’s startlingly frank confessional memoir offers a complex portrait of a brilliant scholar and a profoundly flawed man.

A review of Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative by Glenn Loury, 448 pages, W.W. Norton and Co. (May 2024)

When Sigmund Freud was asked by his friend, German novelist Arnold Zweig, for permission to write Freud’s biography, Freud replied:

No, I am far too fond of you to allow such a thing to happen. Anyone turning biographer commits himself to lies, to concealment, to hypocrisy, to flattery, and even to hiding his own lack of understanding, for biographical truth is not to be had, and even if it were it couldn’t be used.

Truth is unobtainable; humanity does not deserve it, and incidentally, wasn’t our Prince Hamlet right when he asked whether anyone would escape a whipping if he got what he deserved? [Hamlet to Polonius: “Use every man after his own desert, and who should ’scape whipping?”]

Freud did not—as far as we know—feel the same antipathy to autobiography, but surely, when writing about one’s own life, the author is likely to be tempted by the same lies, concealments, hypocrisy, and flattery. Yet in a new memoir from a distinguished black American scholar, the author claims to have cut through these thickets and given the world something like the truth of his life, and the results are often embarrassing or worse.

Brown University economist Glenn Loury’s Late Admissions includes revelations of sleazy and cowardly behaviour usually found in demolitions of compromised public figures written by hostile journalists. Here, Professor Loury takes the hatchet to himself.

Glenn Loury has been one of the most arresting voices on the fraught topic of race in the United States over the past four decades. Now in his mid-seventies (he was born in 1948), he produces a rich and prolific digital output of interviews, debates, and essays on his Substack and his YouTube channel under the title of The Glenn Show. But his voice has not been consistent over the years, as his intellectual curiosity has led him from one side of the political spectrum to the other and back again. From an early age, he flinched from the approved positions and inspirations of young black radicals—Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, and Malcolm X’s Autobiography—and went his own unpredictable way, at times more liberal and at others more conservative.

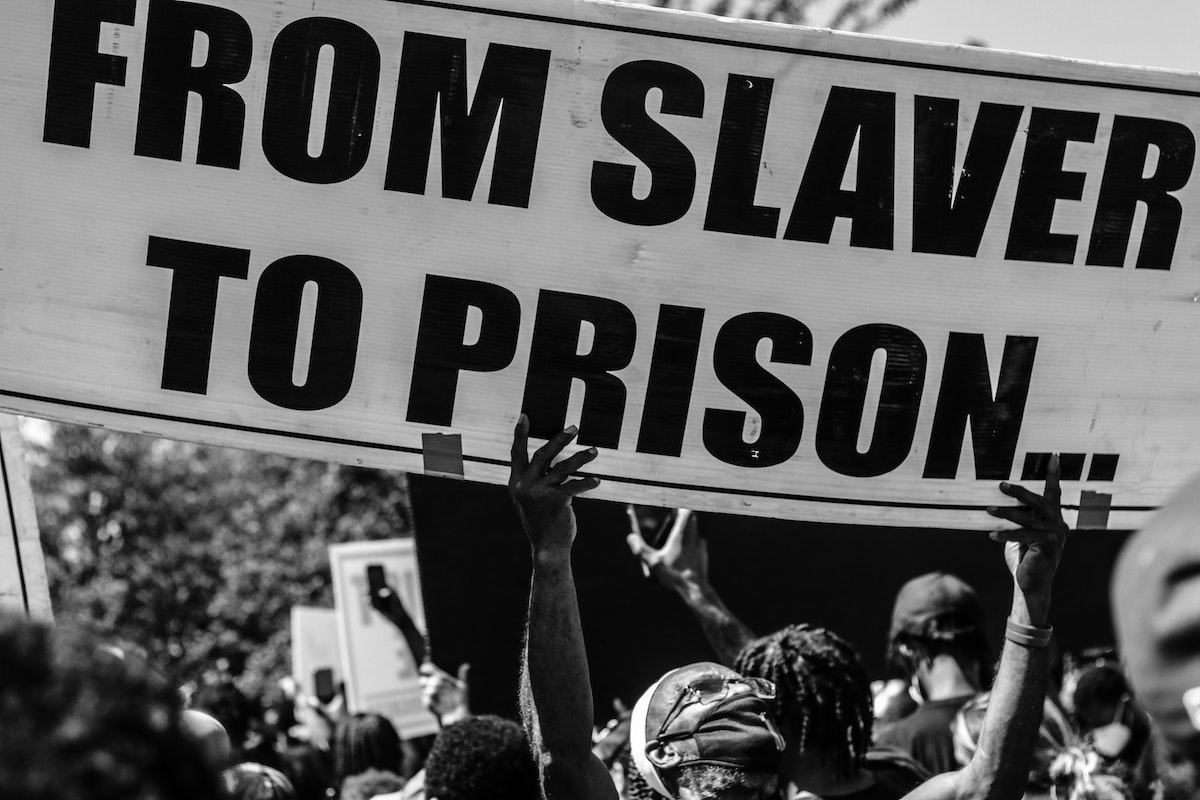

Presently, Loury has settled on being a conservative. His strongly held view—which he shares with his somewhat more liberal sparring partner, Columbia linguistics professor and New York Times columnist John McWhorter—is that the preoccupation with white racism, past and present, as an explanation for black disadvantage is futile. The hard-won rights of black Americans may not have created an entirely level playing field, but they have produced a society in which “structural racism” and “white supremacy” are no longer useful diagnoses of the problems faced by black Americans.

Loury believes that the betterment of black communities primarily rests with those communities themselves, and that it is the responsibility of blacks to tackle damaging cultural proclivities like high rates of fatherlessness, high crime and violence (the majority of which is black on black), low expectations, and poor performance at school and at work. McWhorter has fleshed out this argument in an angry book titled Woke Racism, which argues that contemporary antiracism allows patronising whites to “make black people look like the dumbest, weakest, most self-indulgent human beings in the history of our species,” and to “teach black people to revel in that status and cherish it as making us special.”

Like McWhorter, Loury finds this attitude maddening. In a recent post, he took issue with Joe Biden after the US president delivered the commencement address to graduates at Morehouse College in Atlanta—a formerly religious and now liberal-arts college for black men founded in 1867, two years after slavery was legally abolished. “You would swear it was 1964,” wrote Loury in exasperation. During a speech that Loury described as “self-promoting pabulum,” Biden informed the young black men before him that they would have to work ten times harder than whites, and that, while they may love America, their country “doesn’t always love [them] back in equal measure.” What, Loury asked, is the man talking about?

If you derived all you knew of America only from that speech, you would think it was a racist hellscape where black men are daily gunned down in the street by cops, and those who survive are barred from employment due to the color of their skin. Aside from lip service paid to Martin Luther King Jr. and Richard Coulter, a former slave and one of Morehouse’s founders, barely any mention is made of the work that black people in this country have done to better their own lives, to elevate themselves and their families, and to contribute to the nation. We’re led to believe that only Joe Biden and his promises can save us from the country that he has helped govern for the last fifty-odd years.

He concluded with this:

[Biden’s speech] is an insult to those of us who believe—because we have eyes in our heads—that these young black men’s futures will be determined by their own efforts rather than the politically convenient bogeyman of omnipresent racism.

So, after some years spent dabbling in progressive politics, Loury today has settled back into the cultural conservatism with which he was always most comfortable—challenging the narrative of black oppression advanced by Black Lives Matter and agitators like Ibram X. Kendi, who have made a fortune arguing that whites must prove their opposition to racism by becoming actively antiracist. In Late Admissions, Loury writes, “I had to acknowledge that my social critique and my disposition were better suited to the right. … I was a conservative, and in truth I suspected that is what I always had been.”

Loury’s position isn’t inherently conservative, but it is believed to be so because it is critical of those who call themselves radicals, and because the broader Left tends to align itself with those radicals. However, by recognising the huge legal and social changes that have occurred since the 1960s—many of which were the result of government action and intervention—the so-called conservatives have retrospectively endorsed action once considered radical. The 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1967 Voting Rights Act were both pushed past Southern Democrat opposition by Democratic president Lyndon Johnson. Liberal journalist Adam Serwer has argued that the Voting Rights Act, in particular, “made the U.S. government accountable to its black citizens and a true democracy for the first time.” Clinging to the notion that nothing has changed since the 19th century, Loury argues, has done nothing to assist and much to impede the progress of black Americans. But arguments like these about the nature of American racism, and how liberals and conservatives line up on it are only part of Loury’s memoir.

Late Admissions is an autobiography that strives to reach beyond the limits Freud imposed on such a work. Loury wants to explore the life of a man who journeyed from South Side Chicago to professorships in the most elite of American universities. But along the way, he struggled with what he calls the “enemy within,” which led him into serial adulteries (including with his best friend’s wife), drug addiction, arrogant conceit about his own achievements, and neglect of his own family. The result is a relentless catalogue of betrayal that solicits no forgiveness. “I cannot defeat the enemy within, not entirely,” he writes in the book’s closing paragraph. “To do so would defeat myself, deny my true nature.” He cannot root it out; it lives inside him like the cancer that killed his second wife. And so, he is forced to conclude with the book’s final words, “the game never ends.”

Loury was not born into poverty, but he was born into precarity. His parents were separated and his mother took many lovers—a source of distress to him and of embarrassment to her when he found out. The family was supported by Aunt Eloise and Uncle Moonie—the latter had a barber shop, the back room of which was used to sell marijuana and stolen goods. Uncle Moonie would tell little Glenn that “the white man may have let black folks into the schools and restaurants, but you can call me when they start integrating the money.”

Uncle Moonie was a big-hearted kind of small-time crook, and the money he made allowed Aunt Eloise to supply a small flat in their large house for the Loury family. Chicago’s south side had once been white, but as blacks moved in, whites moved out. Near Uncle Moonie and Aunt Eloise’s house, there was a massive housing estate called the Robert Taylor Homes, which had been built for black families by the mayor-autocrat Richard J. Daley against an expressway, thereby segregating its residents from a white estate nearby. These homes, Loury recalls, were a monument “both to the efforts of the mid-century reformers who took up the staggering challenges of black integration and poverty, and to the resistance and resentment of the city’s white working class.”

Loury went to school but didn’t do well. He was inattentive and preferred to play pool with his best friend Woody, a game at which he became proficient—the first source of pride. He left school in 1965 at the age of 17 and found a place at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he thought his proficiency at mathematics might flourish. It didn’t, and he left with mediocre grades to work in Burger King for a low wage, before finding clerical work in R.R. Donnelly’s big Chicago printing plant, where his pay increased. He took up with a girlfriend, Charlene, got her pregnant, and so they married when Loury was still 18. He would still go out at night with Woody and others, and loved to ride in his secondhand white convertible Plymouth Sports Fury. When he turned 19, he got Charlene pregnant again.

In 1970, Loury then fell for another girl named Janice in the R.R. Donnelly typing pool and got her pregnant, too. She had the child, but Loury couldn’t marry her and wasn’t even sure if the child was his. He reluctantly accepted paternity just the same, and was told to pay Janice monthly support payments, which he didn’t do. That same year, he and Woody attended a meeting of black radicals, at which Woody, who was very light skinned, was aggressively challenged on his ethnicity. Loury could and should have vouched for him, but he let the incident pass without a word lest he be compromised in the eyes of those he hoped would accept him. “I had made a sacrifice of Woody,” he writes, “but a sacrifice to whom, and for what?”

This is hardly the picture of an emerging good citizen, and certainly not of an especially moral one. But as he reached his twenties, Loury began to realise his intellectual curiosity. He read widely and wildly, and by the end of the year, he was accepted—on a full scholarship—at Northwestern University in a suburb of Chicago. There, he began to stretch himself—and to be stretched, since he was still living with Charlene and working to support his young family.

Loury had now entered into the life of his own capacious mind, and his work in the economics department at Northwestern—almost but not quite Ivy League—at last captured that mind, was noticed, and he began to outshine “the polished kids with their prep school education.” He began to publish in small journals. This was at a time—in the 1970s and beyond—when the lack of black academics was beginning to strike liberals as a reprehensible reflection of unconscious, or even conscious, racial bias. In his later twenties and early thirties, Loury began to attract respect for his growing mastery of complex economics. Ahead of others in his class, he would demonstrate his ability by working out equations on the blackboard—“the feeling of power and mastery at the blackboard, or when breaking down a challenging philosophical concept … was an intoxicating sensation, [and] I never wanted it to end.”

By 1972, Loury was sought professionally—by the University of Chicago, by Berkeley, by MIT, and by Harvard. He chose MIT, and though he disliked the middle- or upper-middle-class black students he met—he found them frivolous and self-obsessed, with none of the struggles he had undergone—he was voraciously adopting elite academic manners. He was still with Charlene physically, but they were unmatched intellectually and drifting apart. When Loury brought her to parties or academic events, she would sit miserably while he chatted and networked. “I could feel myself growing and deepening and I did not want to be held back: So I let Charlene sit there, ignoring her obvious discomfort.” Living with carelessly disguised affairs, she finally broke, and locked him out. Loury spent the night at the YMCA, and they parted soon after. “My egotism has become insufferable,” he recalls. “My narcissism reigns. The world begins and ends with me. That is what I think.”

That narcissism, however, didn’t affect his work: he completed his PhD in 1976, and accepted a post back at Northwestern, before moving to the University of Michigan. In the early 1980s, he was approached by Harvard, and unable to turn the offer down, he accepted a post as a full professor of economics and African American studies in 1982. All this was a mere six years after defending his PhD. At first, his efforts to use economics to inform the debate about racism defeated him. He feared that, while his flair for mathematics and economics was considerable, it fell short of extraordinary in an environment where he was surrounded by extraordinary scholars. Still, his acceptance at Harvard, especially when he moved to the John F. Kennedy School, connected him to the world of upper journalism. In 1984, he began to write for the New Republic, where he started to formulate his critique of the assumption that racism remained an intolerable weight on black Americans.

Rising in fame and controversy, he met some of the leaders of the civil-rights movement. They were well intentioned people, he says, but mired in a past increasingly irrelevant to the present. Itemising instances of racism was no longer sufficient to explain why the black areas of cities were riven with violent crime and broken families. “The Civil Rights Movement is over!” he told a gathering of that movement’s great and good, many of whom had read his first piece in the New Republic, in which he had announced his apostasy on the topic of racism. “I assert that the problems of the lower classes of African American society, plagued by poverty and joblessness, are at the end of the day not remediable by the means which had been so effective in the 1960s: protests and petitioning for fair treatment. What we now face, I suggest, is a new American dilemma.” One of the great and good in attendance was Martin Luther King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, who was reduced to tears by Loury’s insistence that she and her colleagues were out of time. “I want to offer her comfort, but it is not my place to do so. That is for the others.”

Loury’s growing fame and his absences to attend conferences and deliver lectures doomed what remained of his life with Charlene and their children. He met and fell in love with Linda, who was herself a scholar in the making—a doctoral student in MIT’s economics programme, where he met her as her tutor. Marriage was soon followed by more children. What did not change was his desire for new affairs and excitement, including a fondness for crack cocaine, which he took to in a big way. As his drug dependence deepened, he hid it from his wife, just as he hid his affairs. “I turned Linda into a sucker,” he reflects. Still, they stayed together, and with her help, after several false starts, he kicked the crack habit.

She may have known or guessed the truth of his affairs, he says now, and he admits to feeling guilty at times, but that guilt was overcome with the defiance of a free man—a kind of Master of the Universe—who deserved to have fun. Among his later transgressions, he had a passionate affair with Woody’s wife Elvie, a betrayal that the friendship was unable to survive. “After their marriage broke up, Elvie came out of the closet as a lesbian. Evidently, her affair with me was only one part of a larger reckoning with her sexuality. As for why I did it, I had no earthly idea. As a budding Master of the Universe, I wanted to do it, so I did.” His affection for Linda remained, however, until she succumbed to cancer after a long struggle.

During his sixties and seventies, Loury has enjoyed a professional life of academic success and acclaim, during which he has reflected seriously on the topic of race in America. He was the first black professor of economics at Harvard and the man approached to give important lectures on the state of black America. These two roles proved to be irreconcilable. “Two decades after I began my studies at MIT, I was still trying to walk both paths—to be an outstanding economist-who-happened-to-be-black, and to be a black economist promoting the uplift of his people.”

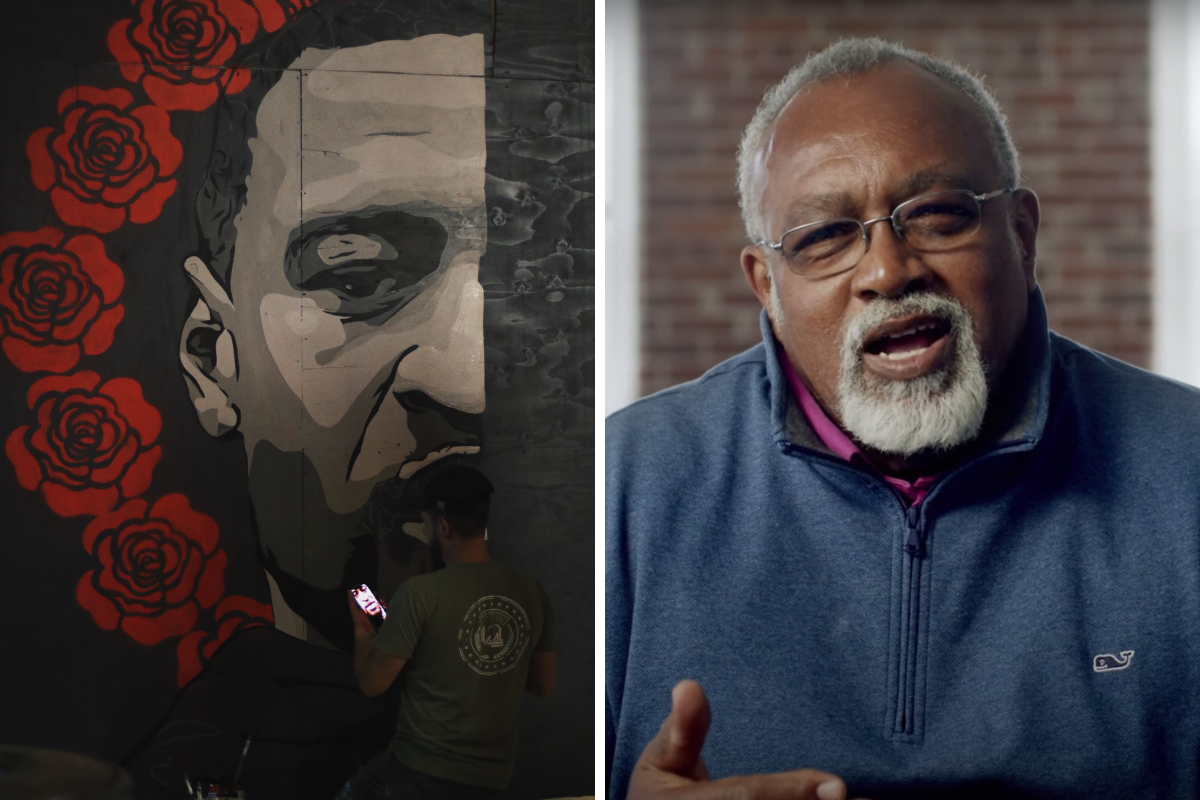

Today, he seems to have got the enemy within under control, although the struggle remains. He retains much of a clever young man’s curiosity, and he and his guests on The Glenn Show thoughtfully explore episodes of the American life—latterly, the killing of George Floyd and its elevation into a great black tragedy. He distrusts this prevailing narrative, but has never been quite sure if he got it right. In the world of political commentary, where pundits on the Right and the Left are so confident about their interpretation of complex events, Loury remains an independent and occasionally uncertain mind willing to examine and follow the evidence—even if doing so leaves the conclusion open.

After a late swerve towards left-liberalism, he swerved back. On this and much else, he has examined his conscience and found that a conservative’s scepticism answers his sceptical nosiness best. And thus he can be the man who chastises the president of the United States for misunderstanding the condition of contemporary black America.

It is a noble folly to do what Loury has done in this book. Its nobility lies in the radical honesty with which he confesses his transgressions and invites us to judge him for the flawed man that he is, implicitly challenging others to do likewise—which of us, after all, should ’scape whipping? Its folly lies in the likelihood that many readers will come away thinking less of him, and might find it hard to see beyond the litany of squalid betrayals to the brilliant social scientist and critic who worked ferociously hard to produce scholarship of a high order, and whose reflections on racism push us to rethink thoughtlessly adopted stereotypes and comfortable illusions.

By the end of the book, we have been provided with ample proof that Loury can be a monumental scoundrel—but to what end? Has the sharp critic of irresponsibility in so much of black life determined that he must take responsibility for his own missteps? Freud would surely have advised Loury not to write this book, had he been asked (and would no doubt have regarded him as a most interesting patient, so sharply varied are the different parts of his character). Perhaps Loury is simply inviting us to look at his horrible self and then to look at his great self, and then to reflect: how much of this is in you, and do you have the guts to display it all for the judgement of others? No, you probably don’t. But I did.