Transgender

In Defence of John Money

How did this famed sexologist become reviled at both ends of the culture-war horseshoe?

Andrea James is a filmmaker and trans activist. Two decades ago, James became well-known as one of the chief tormentors of psychologist Michael Bailey, who’d just published a book about feminine males and male-to-female transsexuals, The Man Who Would Be Queen. In that book, Bailey endorses the theory, originally proposed by American-Canadian sexologist Ray Blanchard, that transgender women typically fall into one of two categories. In the first category are feminine gay men who find it easier to live as women; in the second are straight men who transition because they are sexually aroused by the idea of themselves as female. Perhaps not surprisingly, Bailey’s promotion of Blanchard’s typology enraged some transgender women, including James. (While Bailey was not literally burnt at the stake, he came as close as contemporary civilisation permits.)

To this day, James maintains a kooky website called Transgender Map with many pages devoted to those she sees as “anti-transgender activists.” These include Bailey, of course, but also some impressive journalists, such as the UK’s Hannah Barnes, formerly of the BBC. Quillette, too, features on Transgender Map, with a page that lists almost 70 “anti-trans contributors.”

Another target of James is Dr Miriam Grossman, author of a recent bestselling book, Lost in Trans Nation: A Child Psychiatrist’s Guide Out of the Madness. (Readers might know her as the heroine in Matt Walsh’s 2022 documentary, What is a Woman?.) Grossman believes that the “gender-affirming” protocols now being used by therapists and psychiatrists to treat gender-distressed children are “devastating families.”

James’s Transgender Map catalogues a few friends alongside her numerous enemies—among them the famed gender theorist Judith Butler, whom James correctly describes as “one of the foundational thinkers in queer theory.” Like Grossman, Butler has a recent bestselling book, Who’s Afraid of Gender?

On the question of how we should understand the modern trans-rights movement, Grossman could not be further apart from either James or Butler. And yet, all three of them converge, horseshoe-like, in their scathing appraisals of the late New Zealand-American sexologist John Money (1921–2006). Grossman condemns Money’s theories as “insidious,” and James calls Money “the most unethical sexologist in history.” For her part, Butler denounces Money for his “brutal norms.”

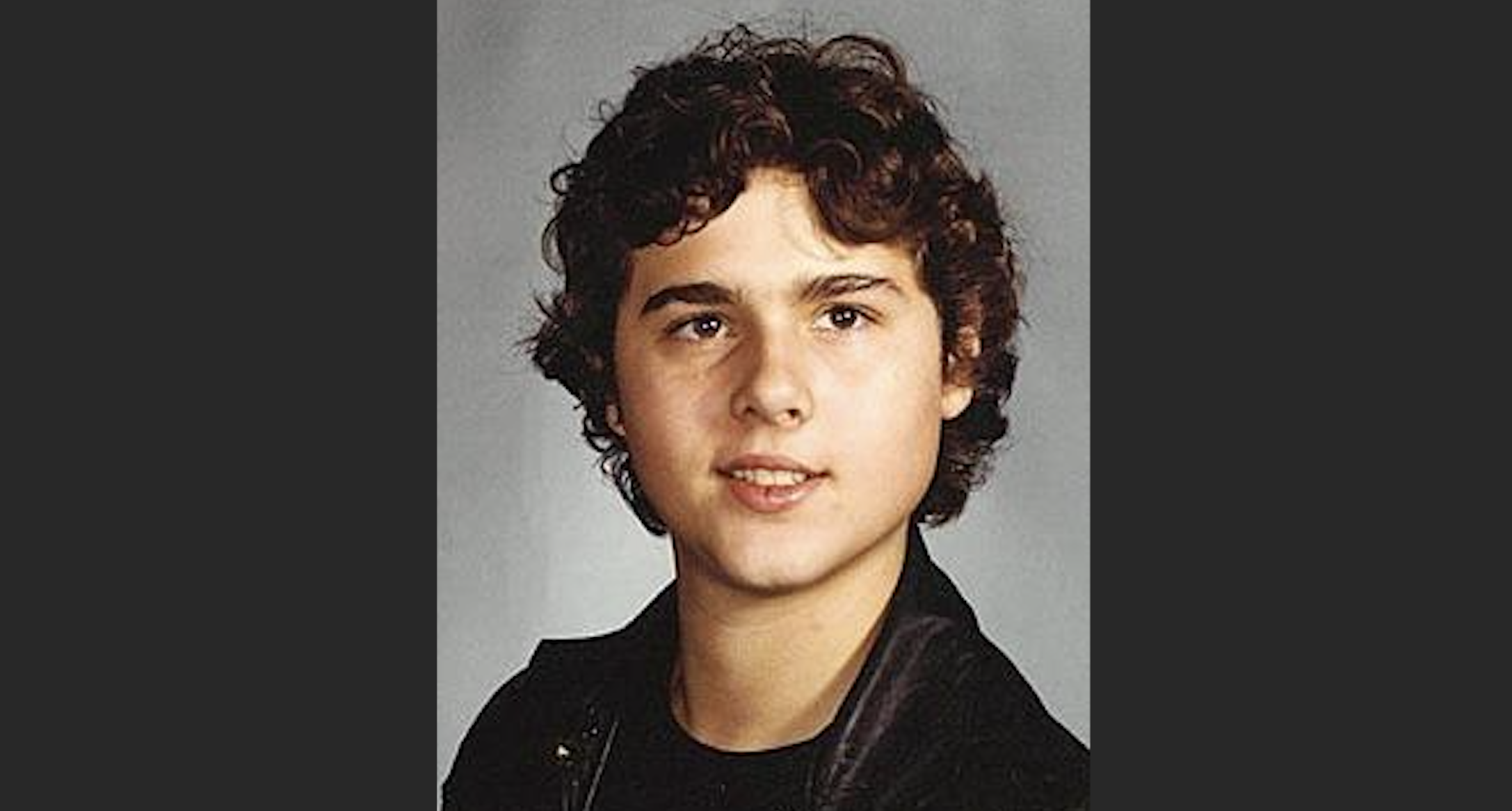

Money is notorious for his role in the case of David Reimer (1965–2004), as popularised in John Colapinto’s 2000 book, As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl. Reimer, a twin son of a Mennonite couple living in Winnipeg, Canada, lost his penis in a botched circumcision, and was subsequently raised as a girl on Money’s advice. As was revealed by Money’s professional nemesis, University of Hawaii sexologist Milton Diamond (who died last March), this plan went horribly wrong. In partnership with Reimer’s former psychiatrist, Keith Sigmundson, Diamond wrote a 1997 article in the Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, which disclosed that Reimer (originally named Bruce) had reverted to living as a male. That, in turn, led to a widely read Rolling Stone exposé by Colapinto, which he later expanded into As Nature Made Him.

As James sees it, “John Money should have died in prison along with other ‘leading lights’ of late 20th-century sexology.” In Who’s Afraid of Gender?, Butler pronounces Money’s “surgical practices” to be “horrific.” Grossman’s verdict is even more damning: Money was “wicked,” “an arrogant psychopath,” and “a degenerate, disturbed man.” One of many charges she levels against the psychologist is that he sexually abused David Reimer and his twin Brian. James is more specific, repeating allegations that Money photographed “the Reimer twins in simulated sex acts.” (Walsh’s documentary relays something similar.)

What’s of more interest than Money’s alleged depravities is Grossman’s claim that Money’s ideas are the source of “(trans)gender ideology”—the “madness” in the subtitle of her book. Gender ideology, Grossman says, “is a system of beliefs” that includes the idea that one’s sex is a matter of how one feels (one’s “gender identity”), and that the preferred frontline treatment for children and adolescents distressed at their sexed bodies is puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. Money’s ideas are not just bad—they “have a body count, and the body count is rising.” For us academics more than satisfied with a rising citation count, that’s some legacy!

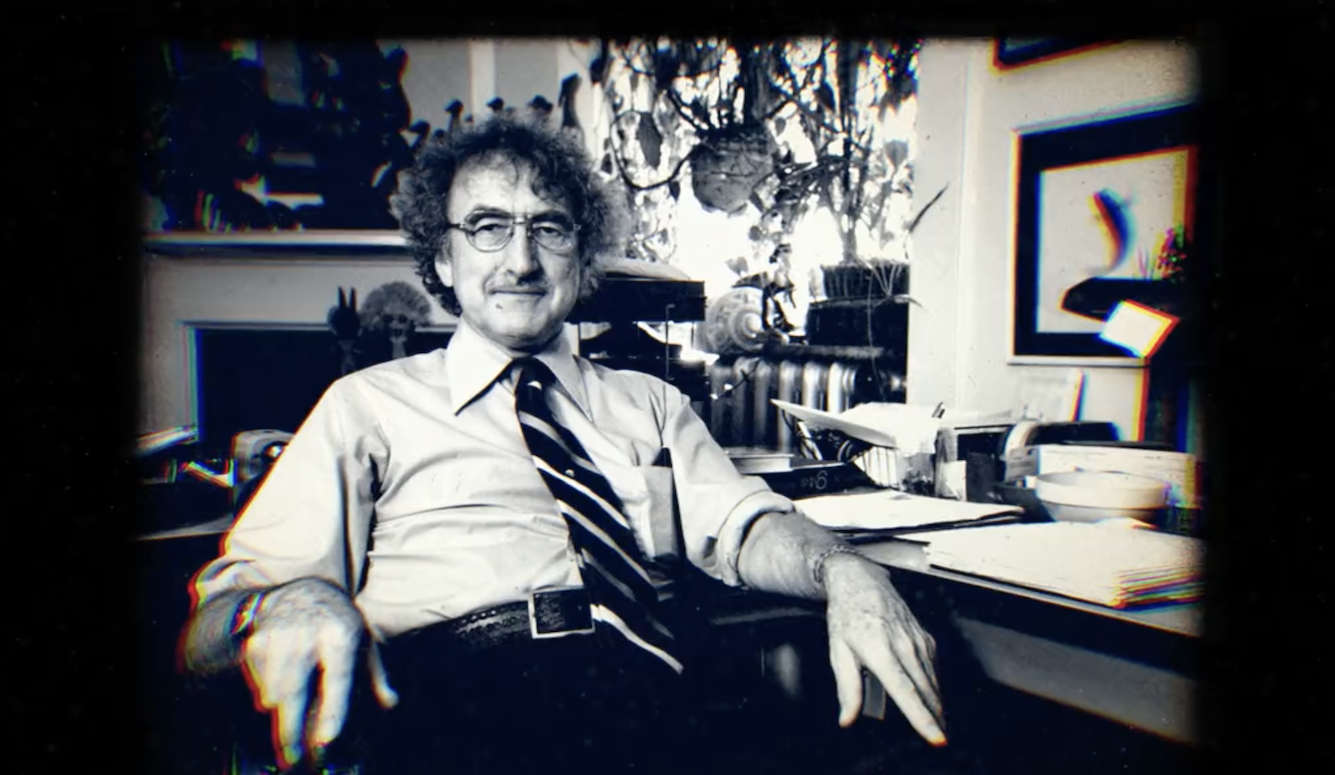

Lethal intellectual or not, Money was a fascinating figure. He was born in 1921 to a poor fundamentalist Christian family living in rural New Zealand. His father died when Money was eight. Grossman writes that Money “grew up on a farm,” attaching some significance to this alleged fact. But Money did not grow up on a farm; in 1927 his family moved to Lower Hutt, an urban centre near New Zealand’s capital, where John would attend high school. Following a family tradition of pacifism, he became a conscientious objector during the Second World War, before starting a PhD at Harvard in the interdisciplinary (and long-vanished) “Department of Social Relations.” With the help of amphetamines, he completed his doctoral thesis, Hermaphroditism: An Inquiry into the Nature of a Human Paradox in 1952 (not the “late 1940s,” as Butler erroneously claims in Who’s Afraid of Gender?), just four years after arriving in Cambridge. He then worked at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland for the rest of his career.

Along with plastic surgeon Milton Edgerton and other colleagues, Money founded the hospital’s Gender Identity Clinic (GIC) in 1966 and became, in Camille Paglia’s 1993-era estimation, “the leading sexologist in the world today.” He had more than a professional interest in human sexuality, enjoying a libertine lifestyle that included sex with both men and women. He arranged evening orgies at meetings of the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality; his friend and colleague Richard Green reported that Money was a “gifted participant.”

If, as Grossman has it, “John Money’s falsehoods are central to the success of the gender blitz,” what were they? Based on his work with people born with so-called “intersex” conditions (“disorders of sex development” is the better term), Money had concluded by 1955 that “assigned sex and rearing” were better predictors of how they would function as adults than their sex chromosomes, gonads, and hormone levels. That is, if a child was assigned female (say), raised as a girl, and (where necessary) nudged in a female direction with medical interventions, she would likely be satisfied with her life as a girl and, subsequently, with her life as a woman. If the child had been born with XY chromosomes, undescended testes and a malformed penis, and had been exposed to male levels of testosterone in the womb, that didn’t matter. What did matter, Money thought, was the critical period very early in life: the assignment as female or male should be made before 18 months of age or thereabouts. Anything longer and the assignment might not stick. He made a comparison with learning a language: anyone can speak a foreign language provided they are exposed to it early in life; becoming fluent when you’re older is much harder.

In Who’s Afraid of Gender? Butler writes that “the corrective surgeries performed during the operation of John Money’s Gender Identity Clinic at Johns Hopkins (1966–1979) were exercises in cruelty.” Butler is clearly intending to criticise corrective surgeries on intersex infants. But Butler is confused: the surgeries that were actually performed at the GIC were of the “gender affirming” kind that she once described as “necessities.” Also, the GIC was not “John Money’s.” Nor was he a surgeon, contrary to what Butler seems to imply. Corrective surgeries on patients with disorders of sex development were carried out before Money’s time and required no encouragement from him to continue. (Compiling all the errors in Butler’s new book would require a level of dedication worthy of Andrea James.)

In a 1955 paper authored with his university colleagues John and Joan Hampson, Money maintained that “it is no longer possible to attribute psychologic maleness or femaleness to chromosomal, gonadal, or hormonal origins.” “A clinching piece of evidence,” he wrote in 1957, concerned pairs of children with the same physical diagnosis, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), in which a female foetus is to some degree masculinised by androgens such as testosterone, produced by over-active adrenal glands. Such children were sometimes raised as girls, sometimes as boys. “It is indeed startling to see,” Money said, a CAH female raised as a girl and another raised as a boy “in the company of one another in a hospital playroom, one of them entirely feminine in behavior and conduct, the other entirely masculine, each according to upbringing.” Put another way, Money is claiming that gendered nurture trumps gendered nature.

And this is what Grossman calls “Money’s dangerous idea”: “Infants are blank slates when they’re born, [Money] claimed, without a predisposition to think, feel, or behave in a masculine or feminine manner.” And if babies are gender-blank slates, then boys could be successfully raised as girls, and vice versa—at least in principle, ignoring the practical and ethical issues.

In Grossman’s telling, the Reimer twins provided the perfect opportunity for Money to test his theory with a normally developed child: raise Bruce as a girl (named Brenda) alongside his twin brother Brian. But Brenda never took to the role, “ripped his dresses off,” reverted to a male name (David), married a woman, and finally took his own life in 2004, when he was thirty-eight. (The family history is tragic all around: Brian died from a drug overdose two years before David’s suicide.) Grossman reports that Money never acknowledged that he was wrong, nor that “David was not born gender neutral,” but “went to the grave knowing he destroyed a family and duped the world.”

Even supposing all the facts arrayed against Money are correct, how does his ‘dangerous idea’ somehow comprise the rotten foundation of gender ideology? Doesn’t gender ideology say the exact opposite?

But even supposing all this is correct, how does Money’s “dangerous idea” somehow comprise the rotten foundation of gender ideology? Doesn’t gender ideology say the exact opposite?

In the words of University of California San Francisco psychologist Diane Ehrensaft—a leading proponent of “gender affirming” healthcare—“a person’s gender identity is an innate, effectively immutable characteristic.” That is why a child suffering from persistent gender dysphoria needs medicalisation, we are told. The problem is a mismatch between the child’s sexed body and their gender identity, and since it isn’t possible to change someone’s gender identity, the only solution is to change the body.

What’s more, can’t the failure of Money’s experiment be taken as support for Ehrensaft’s claim that gender identity is innate and immutable? David Reimer, being a normal “cisgender” boy, had a male gender identity, notwithstanding the physical changes imposed on him after his medical accident. No wonder raising him as a girl was a miserable failure. As Grossman says herself, “David’s biology dictated his identity… his psychological sex, his ‘gender identity,’ was consistent with his chromosomes.”

Here’s physician Joshua Safer, former president of the United States Professional Association for Transgender Health, and another proponent of gender affirming healthcare, drawing a similar conclusion from the Reimer case in 2019:

We cannot change people’s gender identity despite the most intense program for doing so… it’s like the Truman Show… We’re raising somebody from infancy to believe something, having their parents part of the plan and surgically altering their body... And still it fails. If that’s not going to work, I don’t think anything is going to work to change your gender identity.

To be fair to Grossman, she seems to realise the problem with attributing today’s gender dogmas to Money’s influence. “During the decades after Money’s theory was institutionally embraced, and Brenda/David was living in torment,” she concedes, “male and female came to be seen in an entirely new way.” Money, she says, believed that gender identity is “imposed by culture” (and is therefore mutable), a view which sounds transphobic by today’s standards. To the extent that gender ideology stands Money’s idea on its head, he can hardly be blamed for the resulting “madness.”

But there are twists to this tale. The first is that, although Money was originally inclined toward gender blank slatism, he started to change his mind before David Reimer was even born. In a 1965 article, Money reported on experiments with rodents that showed the prenatal influence of hormones such as testosterone on sexual behaviour, and conjectured that “human parallels exist.” He subsequently always conceded an important role to biology. Writing in 1973 about females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, he noted that “they show beautifully the prenatal components of gender dimorphic behavior which, in this particular prenatally masculinizing syndrome, is tomboyishness in the genetic female.” Grossman’s contention that Money was “biophobic”—hostile to biological explanations of behavioural sex differences—simply isn’t true.

Another, more important, twist is that Money’s view about cross-sex child-raising is plausible. The Reimer case is something of an anomaly: there are successful outcomes in similar cases of boys suffering traumatic loss of a penis and being raised as girls. Occasionally, a boy born with a “micropenis” has been raised as a girl: of ten such examples followed up in (mostly) adulthood, all had stuck with the female assignment.

Such successful examples of cross-sex childraising shouldn’t be surprising. Gender blankslatism is false, as Money realised, so boys raised as girls will tend to be more masculine than typical girls, in behaviour and interests. But we already know that masculinity and living as a girl can coexist, as in many well-adjusted tomboys. (Nor is it surprising that masculinity and same-sex attraction in girls can lead to gender dysphoria, given the right social conditions.) And if ordinary boys can be raised as girls with no untoward effects, then that disconfirms a prediction of the fashionable theory that we all have innate gender identities. Ironically, the “dangerous idea” that is genuinely Money’s undermines gender ideology, rather than being its foundation.

What of Money, the man? Did he really abuse the Reimer twins? The source here is Colapinto’s As Nature Made Him, in which David recalled that he and Brenda were forced by Money to “play at thrusting movements and copulation” when they were six years old. However, there is no corroboration, and no similar allegations have been made by anyone else treated by Money. Terry Goldie, the author of a superb 2014 book on Money (which Butler manages to misdescribe in an endnote), writes that these portrayals of Money-as-monster “simply do not conform to the impression conveyed in the conversations I have had with his colleagues and patients.”

Money handled the Reimer case badly. By all accounts, he was incapable of admitting his mistakes, and this was no exception. But the complete fall from grace engineered by both ends of the gender-wars horseshoe—from “esteemed psychologist” and “King of Kink” (as per a 1990 Cosmopolitan interview) to a psychopathic deviant whose ideas have destroyed lives—is quite undeserved. All wars have casualties, and among the many casualties of the gender wars are some remarkable sexologists from the last century. To Money can be added Alfred Kinsey, the American entomologist who in the 1940s turned his taxonomical talents from insects to our sex lives. Grossman says that he was “a degenerate and disturbed man,” too; Walsh’s documentary repeats unfounded allegations of child abuse.

Truth is also a casualty of war, and in this respect the gender wars have laid waste to the countryside. In 1993, not content with claiming that there are three sexes beyond male and female, the biologist and gender studies theorist Anne Fausto-Sterling proclaimed sex to be “a vast, infinitely malleable continuum that defies the constraints of even five categories.” An avalanche of error soon followed: everyone has an innate gender identity, gender dysphoria is a unified phenomenon, the athletic advantage conferred by male puberty is a myth, and who knows what a woman is? Those leading the long march back to reality cannot afford to ignore important sources of insight. And one such source is the work of John Money.