Best of Areo Magazine

The Problem with Utopias

The history of utopian fiction proves that we can’t even imagine a better world.

As progressive politics takes another step towards dominance across the west, there has been yet another resurgence of utopianism. The French Revolution is invoked in the Autonomous Zone of Seattle; there is talk once again of abolishing police forces and prisons; and of having a self-sustaining, global green economy. The World Health Organisation is even claiming that the Covid-19 pandemic could lead us towards a “healthier, fairer, more green world.”

Such declarations are echoes of ideals from hundreds of years ago that come from the playbook of the utopian imagination. There is a general modern belief that the ideal of utopia is the goal that lies behind all manifestations of progress that, as Oscar Wilde puts it, “a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.”

But what do all the utopias imagined from the 1500s to the present day actually look like? Are any of them workable, liveable? After all, political change and social justice must have a goal: we’d be unwise to try to change our societies without some idea of what the perfect future society could and should look like.

You might imagine that there would be a vast, rich, and diverse world of utopias in fiction, a huge map of possibilities, but in reality the genre is not only minuscule but unimaginative, repetitious, and formulaic. Utopian fiction is an unintended testament to the failure of the utopian imagination, and, importantly, this could have a bearing on politics that locate Utopia (consciously or unconsciously) as a destination for humankind.

Utopian Fiction Is an Unpopular Genre for Good Reason

Utopian fiction has produced very few high quality, enduring works: barely forty in the last five hundred years. None have achieved the visibility of the genre’s pioneering tome: Thomas More’s Utopia (1519). Even More’s title points to the impossibility of actualising such a place: utopia means “nowhere” (from the Greek ou “not” and topos “place”).

One of the reasons why utopias are so unpopular is that—unlike dystopias—they present few good opportunities for storytelling and plot lines. Utopias have very little adventure or jeopardy. Even the classics are rigid, with almost no action or tension and narratives that are really just essays full of didactic exposition, as can be seen in New Atlantis, The Isle of Pines, Utopia, A Description of a New World Called the Blazing-World, The Voyage to Icaria, Erewhon, Looking Backward, Walden Two, H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia and Aldous Huxley’s Island. All these fictions depict utopias in which the human emotions of envy, lust, hate, and greed have vanished, and they all use exactly the same pedantic narrative structure.

In each, a stranger discovers a paradise cut off from the world (by sea, mountains, ice, or social planners). The stranger (or strangers) is then given a guided tour by a utopian inhabitant (or inhabitants) in which the laws, mores, and economics of this paradise are explained in great detail. The protagonist is reduced to a simple cypher for the essay-writing author, asking questions like: “tell me, I beseech you—how are your Taxes levied?”—Mercier, The Year 2440 (1771); and “I admit the claim of this class to pity, but how could they who produced nothing claim a share of the product as a right?”—Bellamy, Looking Backward (1888).

This tired literary device trudges its way from More’s original Utopia in 1516 to behaviourist B.F. Skinner’s 1942 novel Walden Two, in which the protagonist asks his tour guides over two hundred questions, including, “But what do children get out of it?” and “May you not inadvertently teach your children some of the very emotions you are trying to eliminate?”

What little plot there is in utopian fiction is usually no more than a debate in the protagonist’s mind, in the last few pages, over whether to remain in the perfect society or not. This small dilemma is sometimes increased by having the stranger be accompanied by one or two others, from the old world, who have differing opinions on the utopia. That’s about it for drama. In fact, as one character in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s all-female utopia Herland (1905) protests, in Utopia “they have no drama in their plays.” As all conflict has been erased from the utopian society, there is no story for a reader to relate to. There is only the task of reading about the efficient running of these perfectly planned, but thoroughly uneventful, lives.

As for the inhabitants of utopian fiction, they are never credible characters, with emotional depth or psychological complexity, precisely because they are without flaws. Throughout the 500 years of the genre, the characters uniformly come across as either brainwashed or bland or as tour guide automatons, mouthing the author’s plans for perfection.

There are no real individuals in utopian fiction, no one memorable—the genre requires this to be the case. This is as true of the Universal Harmony of Charles Fourier (1772–1837) as it is of Aldous Huxley’s The Island (1962). In B.F. Skinner’s behavioural science paradise, the characters enjoy “pleasant and profitable social relations on a scale almost undreamed of in the world at large,” have been genetically or behaviourally modified and must—due to the requirements of the genre—be without anger and the “petty emotions that eat the heart out of [non-utopian humans].” For if the inhabitants of Utopia were like the rest of us—plagued by ambitions, greed, envy, resentment, and lust—the utopia would soon collapse back to the conflict-ridden civilisation that we already live in. The result is that the characters in all fictional utopias are so flawless that they are neither engaging, nor even human.

The Linguistic Tricks of Utopian Fiction

Again and again, utopian fiction employs two linguistic tricks in its attempts to imagine the unimaginable society: a dependence on the hyperbolic repetition of adjectives that signify positive things, like beautiful, joyous, and healthy; and a repetitive use of negated negatives to infer positives: in Utopia, there is no war, no ego, no greed, etc.

William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890) is a case study in wishing a utopia into existence with nothing more than the linguistic trick of positive adjectives. His utopian inhabitants are “handsome, healthy-looking people, men, women and children very gaily dressed … with a pleased and affectionate interest” and “musical laughter,” inhabiting “this beautiful and happy country” that offers “endless wealth of beautiful sights, and delicious sounds and scents.”

Morris’s entire utopia is built upon the adjective beautiful. The children are described again and again as beautiful, the skin of the inhabitants is beautiful, the arms of the women are beautiful—as are the coins, the horses, the rivers, the fields, the glassware, the plates, the rose gardens, the “exceedingly beautiful books,” the weather, the wise women, the young women, the forests, and the architecture: “This whole mass of architecture which we had come upon so suddenly from amidst the pleasant fields was not only exquisitely beautiful in itself, but it bore upon it the expression of such generosity and abundance of life that I was exhilarated to a pitch that I had never yet reached.” Even young girls possess a unique beauty that “was not only beautiful.”

If you were to remove the adjective beautiful from Morris’s utopia, it would collapse. Another utopia completely dependent upon declaring positivity and embroidering it with happy adjectives is James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933). The name of his utopia has entered the language: Shangri-La.

Shangri-La is a place of “total loveliness.” The protagonist’s guides are “good humoured and mildly inquisitive, courteous and carefree” as they tour “one of the pleasantest communities … ever seen.” The inhabitants of Shangri-La live for two hundred and fifty years: “decades hence, you will feel no older than you are today—you may preserve … a long and wondrous youth … you will achieve calmness and profundity, ripeness and wisdom.”

The best written and most imaginative of all utopias is Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915), but it too is almost completely dependent upon the same trick of stringing together long lists of happy adjectives. In this entirely female parthenogenetic collectivist utopia, the children are “vigorous, joyous, eager little creatures,” who “knew Peace, Beauty, Order, Safety, Love, Wisdom, Justice, Patience and Plenty,” in a “big, bright, friendly world full of the most interesting and enchanting things to learn about and to do,” in which “the people everywhere were friendly and polite.”

The Herlander adults are further strings of adjectives: “tall, strong, healthy and beautiful,” with “peace and plenty, wealth and beauty, goodness and intellect.” Again, there is the reliance on the repetition of beauty as a descriptor, in the “rich, peaceful beauty of the whole land.”

Herland also creates its utopia by simply negating things that the author associated with negative experiences. So there are “no wild beasts,” “no criminals,” “no childhood diseases,” “no alcohol,” “no tobacco,” “no competition” and the inhabitants have “no sex feeling” and “no sex.” There is “no marriage” and their houses are thoroughly child-proofed (like other utopias, this one has more than a touch of the infantilising) with “nothing to hurt, no stairs, no corners, no small objects to swallow, no fire.” And, of course, this paradise does not contain the most disruptive element of all. There is “no place for men.”

Negated negatives have a long, predictable tradition that extends all the way into the twentieth century and John Lennon’s hippie utopian anthem “Imagine,” with its “no greed or hunger,” “nothing to kill or die for,” “no countries,” “no possessions,” and “no religion too.”

How a society that has eradicated so many negative things could be achieved by humans is never explained because if it were we would see the question that lurks beneath it all—what is to be done with those human beings who don’t fit the utopian plan?

Eradicating the Non-Utopians

The real consequences of the erasure of negatives become apparent in a utopia that is almost entirely defined by what it is not: Aldous Huxley’s Island (1962). In this lost tropical paradise in which Buddhism is fused with tantra, the inhabitants “do not fight wars,” there is “no established church,” there are “no omnipotent politicians or bureaucrats,” no “captains of industry or omnipotent financiers,” or “any kind of dictator.” How can any of this be achieved? Huxley is a little braver than those utopian writers who skirt around the real consequences of erasing negatives: he advocates getting rid of bad people by “improving the race.”

The spectre of population control also haunts Limanora: The Island of Progress (1903) by Godfrey Sweven. The Isle of Limanora is a scientific utopia, in which technological advances have created advanced computing, communication, and travel for a race who experience great longevity. Sweven explains: “The progressive element in mankind was dragged back by the dead weight of the criminal, the diseased, the habitual pauper and the naturally incompetent.” His utopia was created through the application of “the secret of idlumian”—sterilisation.

Like Sweven, H.G. Wells in his Anticipations (1901) takes the purging of all negative elements from his imagined utopia very seriously, and is not afraid of the human cost. “People who cannot live happily and freely in the world without spoiling the lives of others,” he writes, “are better out of it.” Wells’s utopia requires the mandatory sterilisation of the unfit. Later, in his A Modern Utopia (1905), Wells asks,

what Utopia will do with its congenital invalids, its idiots and madmen, its drunkards and men of vicious mind, its cruel and furtive souls, its stupid people, too stupid to be of use to the community, its lumpish, unteachable and unimaginative people? And what will it do with the man who is “poor” all round, the rather spiritless, rather incompetent low-grade man who on earth sits in the den of the sweater, tramps the streets under the banner of the unemployed.

Wells’ solution is that “the species must be engaged in eliminating them; there is no escape from that, and conversely the people of exceptional quality must be ascendant.”

Wells takes the getting rid of negatives formula found in Morris, More, Bacon, Rousseau, and Gilman Perkins to its conclusion in the systemic murder of those who don’t fit the utopian narrative. H.G. Wells, we must not forget, was one of Joseph Stalin’s “useful idiots.” He had a friendly face-to-face meeting with the genocidal dictator in Moscow in 1934—it is unclear whether Wells was aware that Stalin’s regime had killed 6–7 million people in the two previous years, during the artificially induced Ukranian famine.

Utopian Eugenics

The reason why so many of these writers used the same tropes and held the same beliefs is that their ideas flowed from the same source: the Enlightenment tradition, with its dream of a total science of humankind and a perfectly planned society. Nicolas de Condorcet writes in his Outlines of an Historical View of the Progress of the Human Mind (1795), “this perfection of the human species might be capable of indefinite progress,” “the time will come when the sun will shine only on free men,” and this will be achieved through the “annihilation of the prejudices.” During the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror, the annihilation of prejudices also involved the annihilation of the lives of those thought to hold prejudice. Condorcet’s sun did not shine on the 18,000 dead.

The Enlightenment dream of a perfectible human species found its logical conclusion in the thinking of the highly influential Sir Francis Galton (1822–1911): polymath, meteorologist, anthropologist, inventor, and half-cousin of Charles Darwin, a self-described progressive and a proto-geneticist. The ideas of the Enlightenment and of Galton can be found in most utopian fictions from the 1800s up to the second half of the twentieth century.

Galton’s theories of the stabilisation of the population and the genetic improvement of the human species evolved into eugenics. Eugenics made the beautiful, super-intelligent, disease-free, strong children that utopian writers had been imagining for centuries seem like a real-life possibility. This strand of thinking led directly to the introduction of a Eugenic Sterilisation Law in 1933, under Adolf Hitler, and the elimination of “genetic undesirables” in the Nazi Final Solution.

This is neither an accident of history nor a coincidence. Hitler was also the creator of a utopian fiction. His Third Reich, with its imagined city of Germania, was the tragic conclusion of those two strands of utopian thinking: positivistic hyperbole and the negation of negatives. Of his utopia, he writes, “the Crimea will give us its citrus fruits, cotton and rubber … The Black Sea will bring us a sea whose wealth our fisherman shall never exhaust. We shall become the most self-supporting state … in the world. Timber we shall have in abundance, iron in limitless quantities, the greatest manganese ore mines in the world, oil—we shall swim in it.”

We now know that his euphoric eradication of negatives was literal genocide. As a result, after World War II, the utopian tradition fell into disgrace.

Its problems, however, have been present since the very start of the genre. The very first utopian text, Plato’s Republic (360 BCE), depicts a perfectly planned state, designed to create peace, harmony, and justice for all, but in which artists are banished to die in the wilderness, wives and children are communal property, parent–child bonding is prohibited and eugenics is enforced through selective breeding under a military dictatorship ruled by a philosopher king: “the bride and bridegroom must set their minds to producing for the state children of the greatest possible goodness and beauty.” Plato’s utopia is also held together by “the noble lie”—a policy of systematically lying to the citizens, “to keep them content in their roles.” All roles are dictated and enforced from above. This first utopia is a totalitarian state built on eugenics, and it is the deep well from which all future utopias draw their ideas.

Even an anti-statist utopia like that of the Digger Gerrard Winstanley’s The Law of Freedom in a Platform (1651) generally harbours a tyrannical plan. In his utopia, in which money is abolished, anyone who buys or sells anything or who administers the law for money or reward is to be executed.

Dystopian Fictions Are More Socially Useful

While utopian fiction is locked into its own rigid form, dystopian fiction has expanded in hundreds of narrative directions from its roots in the tragic worldview that we have inherited from Aristotle’s theories of dramatic tragedy. These narrative forms are based on hamartia and pathos: tragic events unfold as a result of the fatal flaws of credible characters whom we feel and fear for. Fictional worlds that rely on all-too-human flaws are usually both credible and hugely compelling, no matter how futuristic or fantastical they may be.

Dystopian fictions number in the hundreds of thousands: there are over three hundred classics and hundreds of thousands of fans have created their own fan page dystopias online. One website alone contains 37.8 thousand The Hunger Games fan fictions. Films based on dystopian fictions are a vast socioeconomic and cultural phenomenon (see The Hunger Games, Blade Runner, Aliens, Logan’s Run, The Matrix, 1984, Divergent, The Giver). The Marvel brand is the single biggest cultural franchise in the world and it is essentially dystopian.

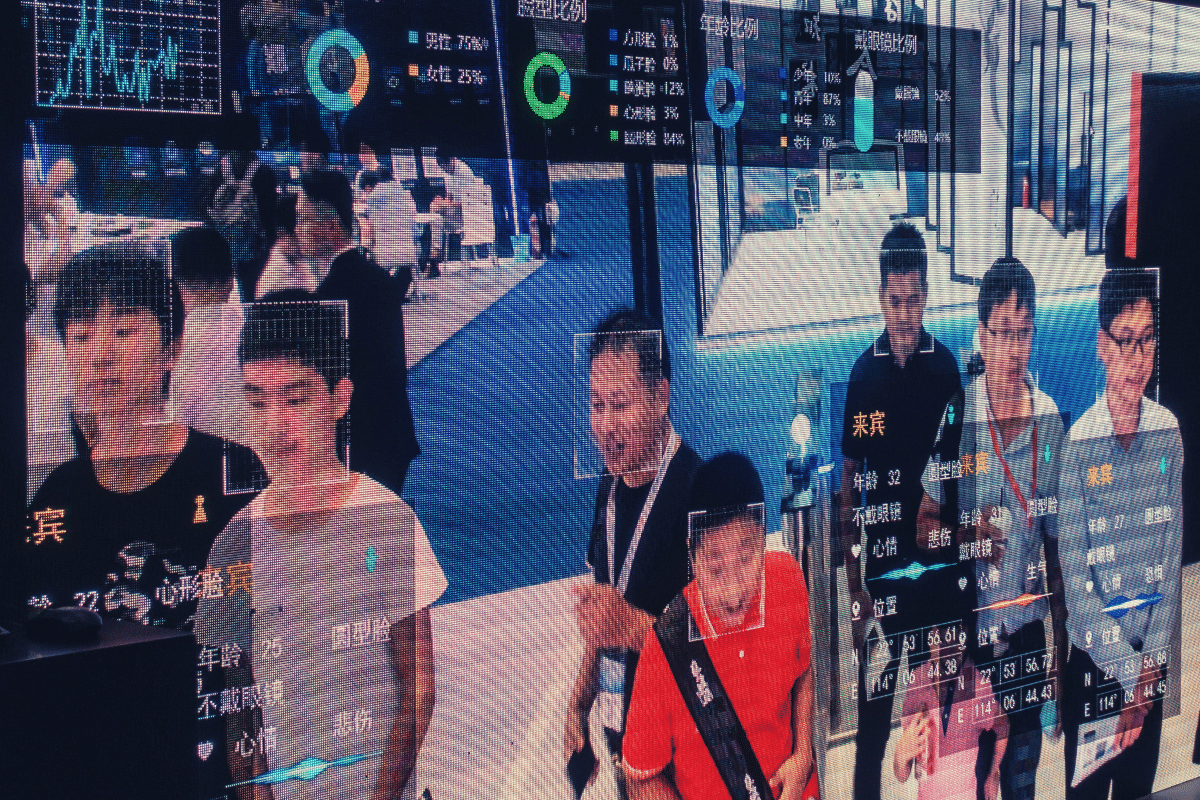

While utopian fiction has inspired failed and often horrific experiments in social engineering, the real-life impacts of dystopian fiction have, ironically, proven extremely socially useful. In day-to-day democratic debate, we use metaphors and phrases from dystopian fiction as navigational tools and to set boundaries against oppression. We talk of the encroachment of government surveillance by referencing Big Brother and 1984. We warn about the militarisation of Artificial Intelligence by referencing Terminator. We debate whether The Matrix predicts a post-human future and talk about “taking the red pill.” We use environmental dystopias like The Road, Day of the Triffids, Mad Max, and The Day After Tomorrow to alert people to climate change, and we use The Handmaid’s Tale to warn against the dangers of polarised gender politics and statism.

Utopian fiction fails because it is fundamentally at odds with human psychology and the human condition. It is a social constructionist fantasy of a blank slate society, with infinitely malleable inhabitants from whom all traces of human nature and history have been removed by social engineering or re-education. As H.G. Wells realised in later life, “all Utopias are static”—that is, they are authoritarian, since all inhabitants are forced to live under the inflexible, unchangeable regime of the creator’s masterplan.

Our inability to create credible utopian fiction shows why, throughout history, experimental communities and states based on utopian ideals have either collapsed or become totalitarian regimes—and will continue to do so in the future. The inability to address real human failings, desires, and conflicts within the utopian imagination is a symptom of its inherent inhumanity.

It’s time to take an honest inventory of the outcomes of the utopian ideal. We might want to give up on the idea, which resurfaces every second generation or so, that the only things stopping us from creating a newly revised utopia on earth are lack of imagination and political will. It is not simply bad or uneducated people who stand in the way of realising this secular heaven on Earth—the flaw lies within the utopian ideal itself.

As Ursula Le Guin shows us in The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (1973)—and, as we see in W.F. Nolan’s Logan’s Run (1967) and Veronica Roth’s Divergent (2011)—the sure path to hell on earth is to attempt to force one single plan for utopia upon everyone within a diverse society. Many dystopian fictions are based on this model of a false utopia, a utopia-gone-wrong, such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Lois Lowry’s The Giver.

There are even some authors who started writing utopias, only to realise that they had accidentally created hells on Earth. One such is Gabriel de Foigny (1642–92), whose protagonist in A New Discovery in Terra Australis (1693) begins with a unisex tribal utopia and concludes with the protagonist condemned to death along with the enemies of the Utopians—women and children from another tribe who have their throats slit in their thousands, and are left in huge rotting heaps for the birds and beasts to devour. His crime was the human weakness of pity for the non-Utopians.

For all its hell and suffering, dystopian fiction is the more humane genre: it provides a warning against the utopian hubris that aims to create perfect planned societies, while sacrificing what makes us human.

The failure of the utopian fiction genre highlights a pressing political question: if no one in history has ever managed to imagine a credible, functioning utopian society that is not founded on the eradication of everyone it deems politically unfit, why should we keep on attempting to steer our existing societies towards a land we can’t even usefully imagine?