Ancient History

Merry Christmas, Little Wolf

Christmas offers a chance to remind ourselves of the intellectual debt that our editors and writers owe to the Christian tradition.

While Quillette is not a religious publication, Christmas is a good time to remind ourselves of the debt of gratitude that even secular intellectuals owe to the Christian tradition. As the historical essays that Quillette has published over the last year help illustrate, the earliest Christian missionaries didn’t just spread Jesus’ teachings, but also helped develop the enduring literary habits and skills necessary for their widespread study and dissemination.

By way of case study, consider the two ancient pre-Christian peoples—Goths and Huns—whose sweep through Europe during the twilight of the Western Roman Empire has been vividly described by Quillette contributor Herbert Bushman as part of his ongoing So-Called Dark Ages series.

Both formed pre-literate societies led by warrior chiefs—the Goths being descended from Scandinavian settlers who’d crossed the Baltic, while the horse-mounted Huns stormed out of the vast Eurasian Steppe. During the late fourth and fifth centuries C.E., both groups roamed Europe, fighting against each other, Romans, and numerous smaller tribes. Both came to dominate large swathes of territory, and both repeatedly invaded Rome’s Italian heartland. But when it comes to the scope of our knowledge in regard to these two cultures—their mythology, faith traditions, and languages—the similarities end.

Though the Gothic tongue has been extinct since the ninth century, much of it has survived in written form, including about 2,500 known words. Gothic texts have been studied extensively by modern scholars, who’ve used them to tease out fascinating details about ancient Gothic life.

In the case of the Hunnic language, by contrast, the total number of known surviving words is, at most, three: medos (an alcoholic beverage made from fermented honey), kamos (another drink, this one produced from barley), and strava, a funeral feast. And of this trio, only the third term is certain to have been Hunnic.

Scholars can’t even agree on whether the Huns’ language originated in Turkey, Mongolia, or some place in between. For all of Attila the Hun’s legendary military conquests, his people’s stories have been completely lost to history, except to such extent as they were recorded by his enemies in alien tongues.

To what do we owe this vast gulf in our knowledge as between Goth and Hun? The answer largely comes down to the work of a single Gothic writer, known to history as Ulfilas, a word that translates to “Little Wolf” (𐍅𐌿𐌻𐍆𐌹𐌻𐌰).

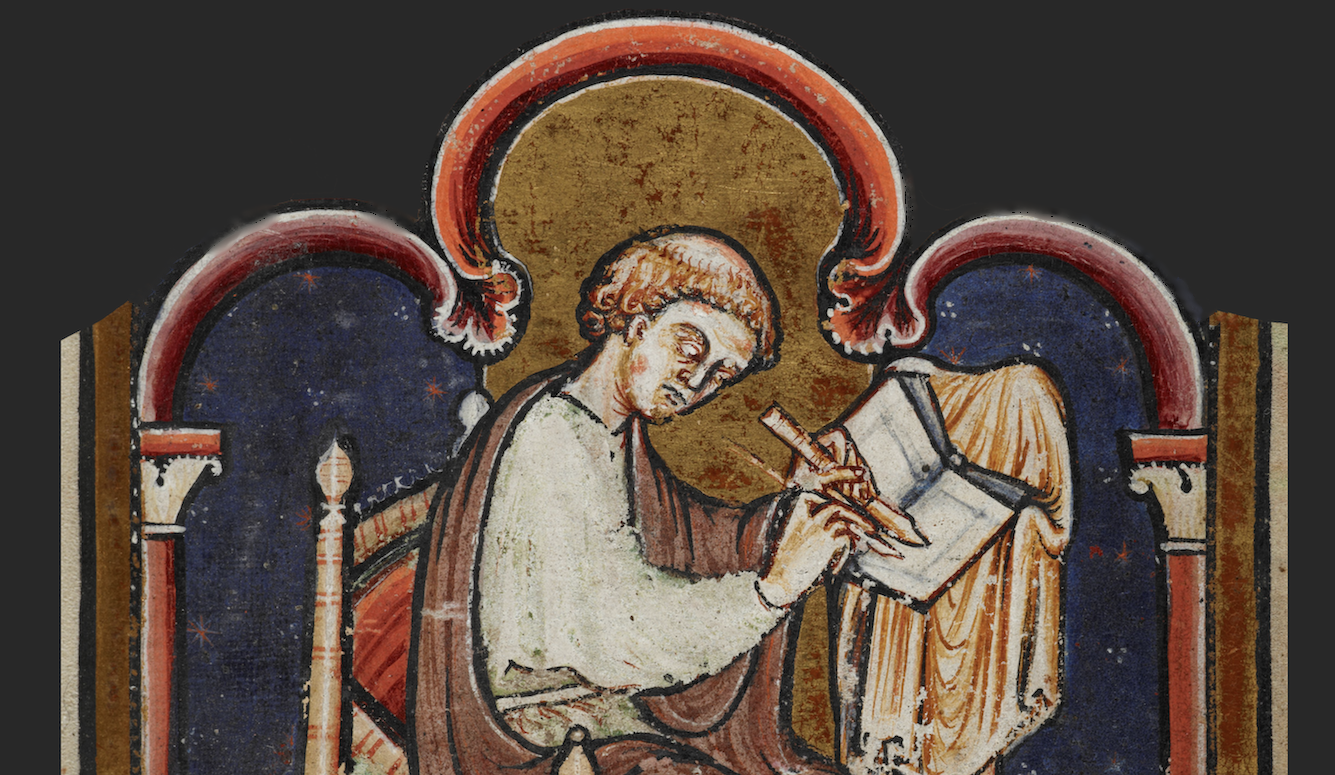

During the third century, Gothic raiders abducted Ulfilas’ forebears from their home in Cappadocia, on the northern coast of modern Turkey. Growing up in what is now Romania, Little Wolf became fluent in Gothic, Latin, and Greek. He also became a fervent Christian believer who would go on to be ordained a Bishop by no less a cleric than Eusebius of Nicomedia, famed for having baptized Constantine the Great on the Emperor’s deathbed.

After being expelled from the Visigoths’ pagan society, Ulfilas led his small band of Christian acolytes to a refuge in what is now northern Bulgaria, whereupon they commenced creating a Gothic-language Bible—a monumental task made more difficult by the fact that there was, as yet, no Gothic alphabet. Ulfilas had to invent one.

Many Gothic Christians would become martyrs for their new faith. But in time, Ulfilas’ missionary efforts bore fruit when the chieftain Fritigern (whose exploits are discussed in Bushman’s second Quillette instalment) brought his followers over to Christianity. By the time the Goths took over the Italian peninsula in the fifth century, they’d become a Christian people.

You don’t have to be a religious Christian, but merely a passionate student of history and language, to feel indebted to Ulfilas’ ministry: The surviving passages of his Gothic Bible, set beside corresponding verses in Greek and Latin scripture, delivered to us a sort of Eastern European Rosetta Stone.

Ulfilas is hardly alone: In many parts of Europe, texts produced by Christian bishops and monks served to illuminate periods of the Dark Ages that would otherwise comprise historical black holes. Their churches and monasteries often were islands of learning in vast seas of illiteracy.

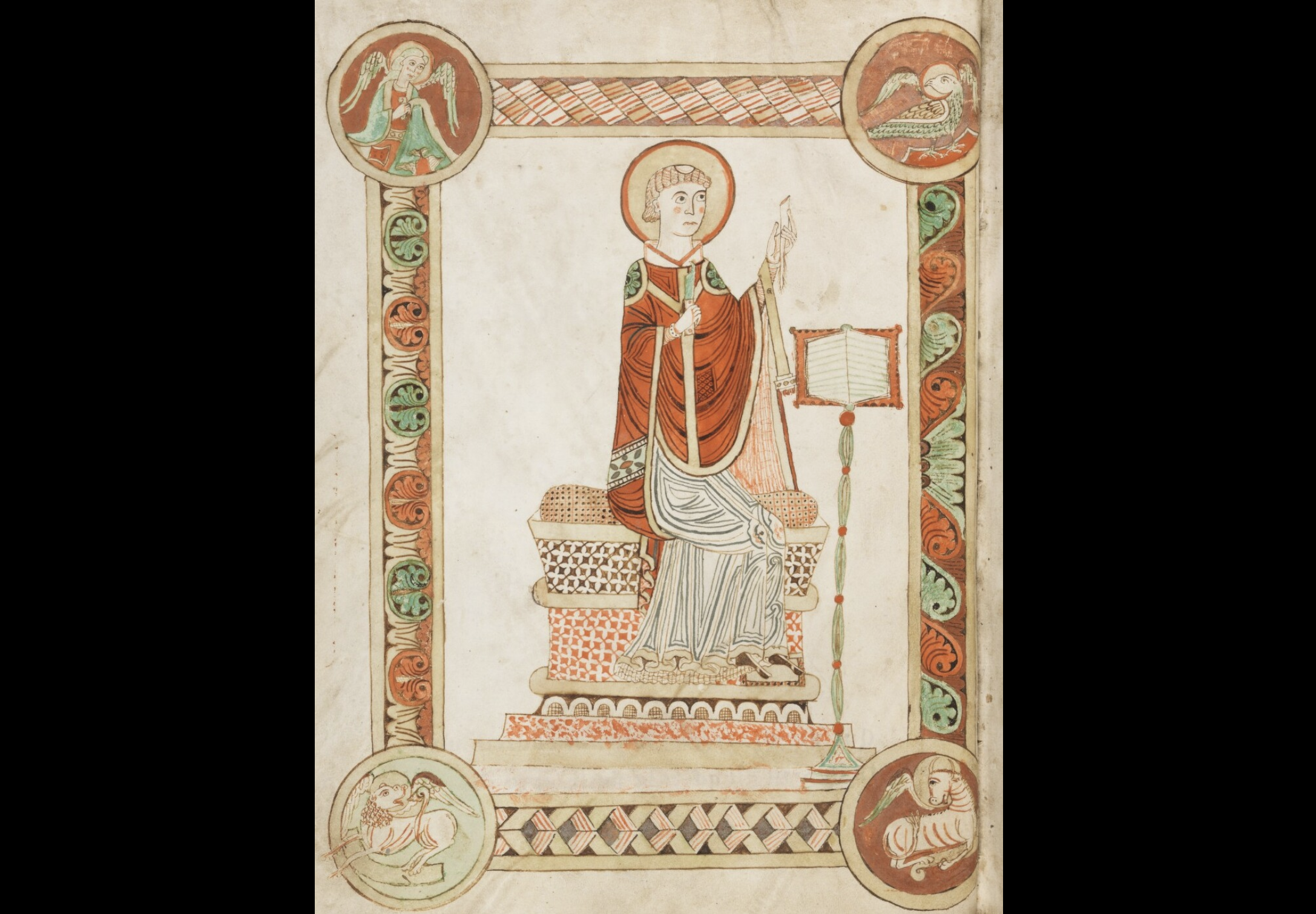

Almost everything we know about Anglo-Saxon politics and warfare during the 600s and 700s, for instance, comes from Bede the Venerable, an English monk who served at the twinned monasteries of St. Peter and St. Paul in what was then the Kingdom of Northumbria. Likewise, our knowledge of Merovingian history would be almost nil without (Saint) Gregory of Tours’ Historia Francorum. The same goes for late Roman Spain but not for the (admittedly quixotic) chronicles of Hydatius, who produced his apocalyptic accounts while serving as bishop of Aquae Flaviae in modern-day Portugal. These are but a few examples, plucked at random from a Quillette editor’s memory. Any medievalist could easily provide dozens more.

These men didn’t see themselves as writers, authors, or historians in the modern sense of those terms. Like Ulfilas, they defined their mission as spreading God’s message, often by celebrating the miraculous deeds of great Christians (as with Gregory’s Life of the Fathers, which contained no fewer than twenty hagiographies). They often explained the wars, plagues, and invasions they witnessed by reference to sinful behaviour that, they believed, had elicited God’s wrath.

Indeed, many of these Christian proto-historians were quite anxious about their own sinful souls—and so created a kind of inward-looking biographical literature that, in its way, anticipated recognizably modern confessional genres. One notable example here would be Evagrius Ponticus (known to fellow fourth-century monks as “Evagrius the Solitary”), whose extreme religious dedication caused him to eat but once per day, sleep only a few hours each night, and (alas) abstain entirely from bathing. The sheer scale of his oeuvre would be the envy of any modern writer, and includes such classics as Antirrhêtikos, a treatise cataloguing the 498 temptations that Christians must face. (During his licentious youth in Constantinople, Evagrius apparently encountered most of them.)

These men spent a lot of time calling out the perceived theological errors of their peers—as in 708 C.E., when Bede was accused of committing heresy in his treatise De Temporibus (The Reckoning of Time) by concluding that the world was a mere 3,952 years old at the time of Christ’s birth; when, of course, every respectable theologian of the period followed the lead of Isidore of Seville, who’d confidently asserted that the correct figure was over 5,000.

In many parts of Europe, texts produced by solitary Christian bishops and monks illuminate periods of the Dark Ages that would otherwise be a complete mystery to modern historians.

As obscure and pointless as such debates may seem to modern ears, it is these ancient underlying fixations of Christianity—policing of doctrine, eradication of heresy, celebration of piety, explanation of evil, confession of sin—that kept medieval monks scribbling away. In doing so, they refined the craft of debate and disputation they’d inherited from secular Greek and Jewish Talmudic traditions, preserved fragments of otherwise departed languages and cultures, and assembled (by hand, of course) the precious paper trail that would eventually allow us to know the events of their time.

For believers and non-believers alike, the holidays are a time for expressing gratitude. In that spirit, let us raise a glass of medos, kamos, or whatever else is at hand, and say: Thank you, Ulfilas, Bede, Gregory, Hydatius, Evagrius, and all the other ancient Christian thinkers who, by setting down the words and histories of their ages, helped forge the tools of language we use to make sense of our own.