So-Called Dark Ages

Huns to the North. Romans to the South

In the second instalment of ‘The So-Called Dark Ages,’ podcaster Herbert Bushman describes the events that sparked the fateful Gothic invasion of the Roman Empire.

What follows is the second instalment of The So-Called Dark Ages, a serialized history of Late Antiquity, adapted from Herbert Bushman’s ongoing Dark Ages podcast.

I left off our story last time with the defeat of the Gothic leader Canabaudes by the Roman Emperor Aurelian in 271 C.E. That successful campaign led to a period of peace on the Empire’s Danube frontier. This was part of a larger pattern during Aurelian’s five-year reign, which marked the beginning of a startling recovery of Roman fortunes in many regions.

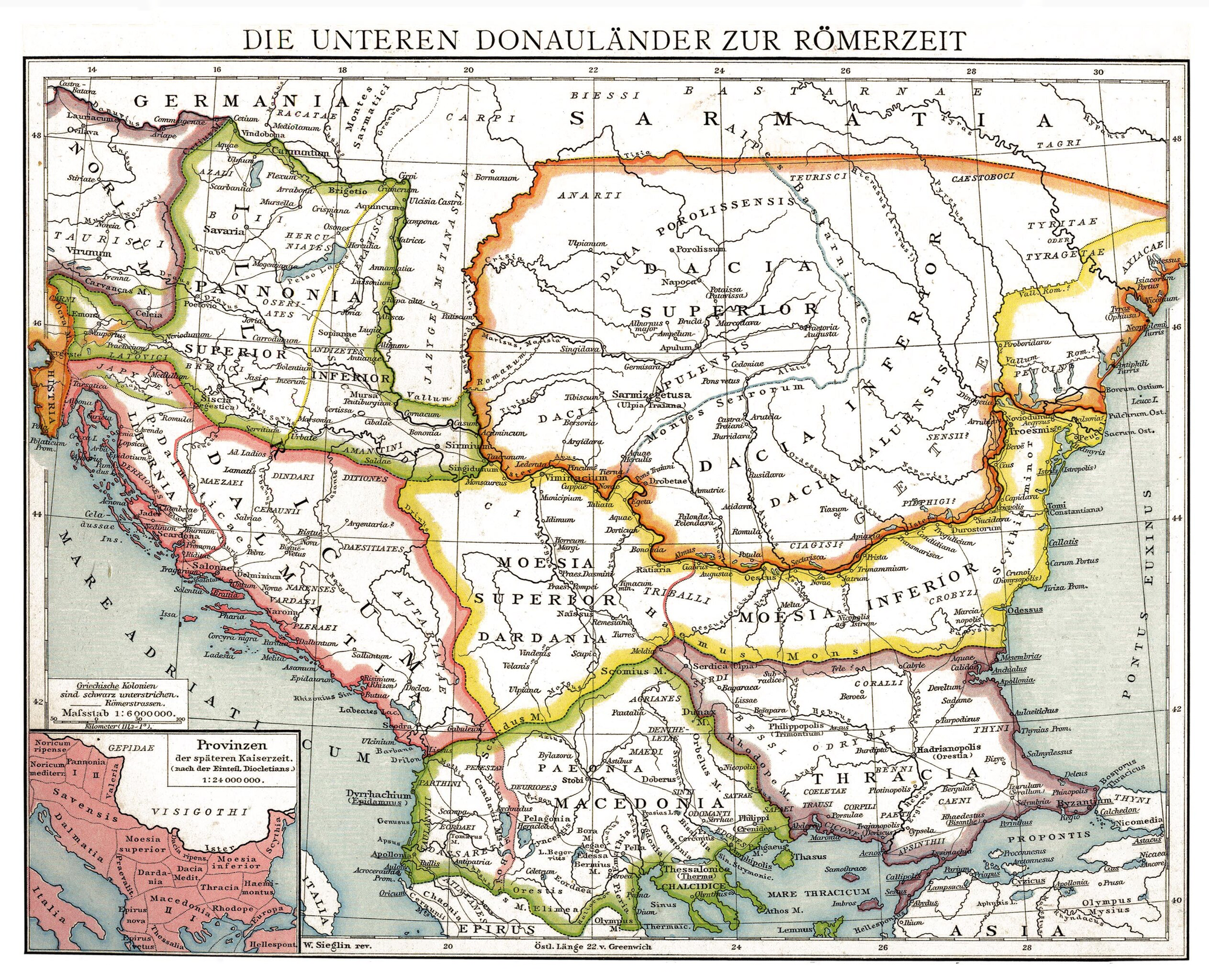

Part of Aurelian’s strategy for strengthening Rome, however, involved retreat. The Roman province of Dacia Traiana, corresponding roughly to modern Transylvania, was militarily exposed on the north side of the Danube, with no strong natural borders to protect it. There had been rich gold mines in operation when Trajan (r. 98 to 117 C.E.) had seized the area in the second century, but those were played out, and Aurelian could see that defending Dacia Traiana was no longer worth the effort or expense. And so Roman power was gradually withdrawn—an organized and orderly retreat, but a retreat nonetheless.

Following an age-old historical pattern that has persisted into our own era, the withdrawal of colonial power triggered a struggle for dominance among those left behind. Dozens of tribes vied with each other for the abandoned territories, including the Vandals (whom we will study in more detail in future instalments), and a tribe called the Taifali, which ultimately made common cause with the Gothic branch known as the Thervingi (as distinct from the Greuthungi, the other major Gothic group that will be discussed in this instalment).

Together, these groups managed to take complete control of the region by 350 C.E. at the very latest. The Taifali became the Thervingi’s cavalry partners, and they would eventually extend their reach from the Hungarian Plain across the Carpathians, to Ukraine and Southern Russia, and northward all the way to the Baltic. (Eventually, the Romans would settle the Taifali in what is now France. And to this day, the town of Tiffauges, in western France’s Vendée region, bears their name.)

And it was around this time that a new element found its way into Gothic society: Christianity.

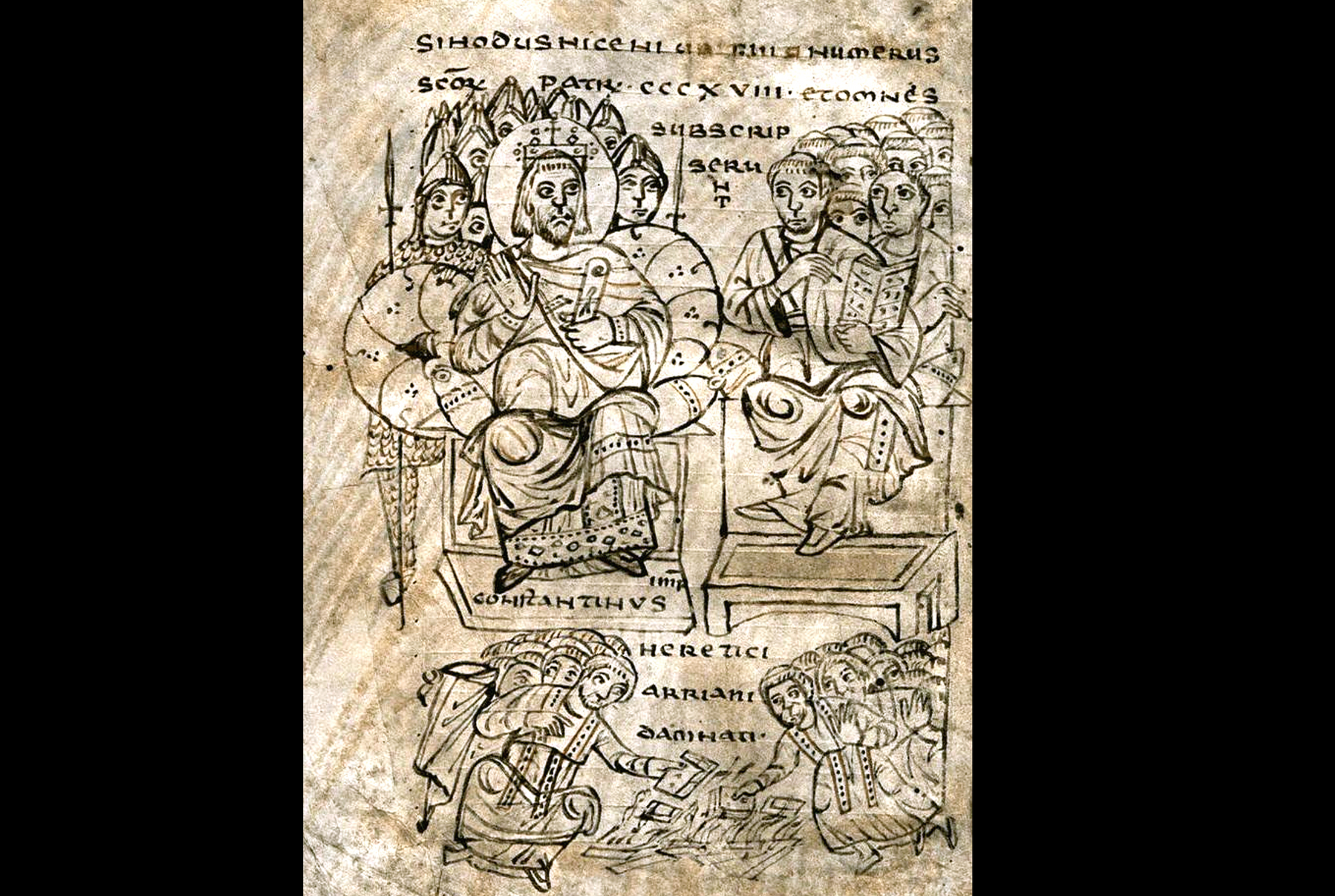

The Gothic Black Sea raids of the third century had been aimed as much at the capture of slaves as at material riches. Among those slaves captured from Roman farms and towns were a significant number of Christians. Soon, those new arrivals began to have an impact on their captors. Christian communities grew in Gothic areas, thereby creating a demand for priests and teachers. And as things turned out, the strain of Christianity that happened to be injected into the Gothic body politic was a creed known as Arianism.

Arian theology, whose conception has traditionally been attributed to a north African priest named Arius, taught that Jesus, being the Son of God, was not coeternal with God the Father. In this regard, it contradicted what would become the dominant Christian orthodoxy, which presented Jesus as “consubstantial with the Father.” While that may seem an esoteric distinction, this theological schism remained a serious (and at times bloody) threat to Christian unity until the seventh century C.E. And for our purposes, it’s important because the Gothic embrace of Arianism would remain a significant factor in Gotho-Roman relations for two and a half centuries.

I have already briefly mentioned Ulfilas, the Gothic missionary who led the Christianization of his people. And it’s now time to introduce him properly. He was of Cappadocian descent, with his ancestors having been taken as slaves around 264 C.E. from near the city of Parnassus, in what is now central Turkey. (Parnassus was pretty much right in the center of the Anatolian peninsula—so that’s an indication of how deeply those Gothic seaborne raids penetrated the Roman heartland.)

His family appears to have been fairly well-integrated into Gothic society by the time of his birth in around 311 C.E. However, the details of his early life are sketchy because of the doctrinal differences among the sources, with Arian and Orthodox authors both seeking to use his story for their own ends.

We know that he travelled inside the Roman Empire, though we have no idea under what circumstances. He was consecrated as a bishop in 340 C.E. by Eusebius of Nicomedia—the same Eusebius who’d recently baptized the Emperor Constantine on his deathbed. So Ulfilas obviously had, by this time, attained some degree of status as a Christian.

He then returned to his homeland and evangelized among the Goths for seven years. Exactly how successful he was depends on what source you’re reading. Arian sources credit him as being essentially the Saint Patrick of the Goths, while Orthodox sources give more credit to others. Either way, the new religion gained enough of a foothold in his time to spark a reaction—which is to say, a persecution campaign led by some of the Goths’ more traditionally minded (i.e., devoutly pagan) leaders.

In the face of this opposition, Ulfilas requested, and received, Roman permission to immigrate southward with his flock, into Moesia Inferior. (Moesia consisted of the plain that extended northward from the Balkan Mountains to the Danube River, with the “Inferior” part indicating that it was along the lower reaches of the river, closer to the Black Sea.) After settling in this Roman-controlled region, Ulfilas’ group would become known as the Gothi minores, or the “little Goths.”

The move had advantages for all parties; the Gothi minores gained a homeland free from religious persecution, land to farm, and the protection and support of the Roman Empire. The Romans, for their part, were gaining a group of immigrants who could generate tax revenue in an underpopulated region. According to their agreement with the Romans, these Goths would also provide the Romans with troops. (Recruitment was a constant issue for the Romans, and the problem of defending the Empire’s long borders was never really solved.) In the relatively peaceful climate that now prevailed on the south bank of the Danube, Ulfilas led his great project of translating the Bible into his native Gothic—after inventing an alphabet for it.

Not all Gothic Christians followed Ulfilas across the river, however. Communities remained embedded in their traditional village milieus, quietly (or not so quietly) practising and preaching their faith.

The problem presented by Christianity to Gothic chiefs was the same problem it had presented to Roman emperors; it suggested a split in loyalties. Every reiks (tribal leader) traced his lineage, and therefore his authority, back to an ancestral god. And so the Christian insistence on the illegitimacy of those pagan gods was a challenge to the legitimacy of the reiks himself.

The response to such a challenge was obvious: the Christians would have to go. And Gothic persecutions of Christians took a form similar to the campaigns carried out by the Romans against both Christians and Jews. Villages were ordered to sacrifice to the ancestral gods, by killing an animal in the gods’ name that was then shared out in a ritual meal. Refusal to take part in either the sacrifice or the meal was taken as proof of unacceptable beliefs. A first offense usually resulted in banishment from the village—a harsh sentence in a collectivist agrarian society.

But as we see from the story of Sabbas the Goth (334-372 C.E.), a Christian martyr, such individuals often were readmitted to their villages as soon as the chief’s men had disappeared over the horizon. For most Goths, the first loyalty was to the immediate family and clan in the village, not to the reiks.

When the Gothic authorities returned to the village, Sabbas was seized again. But he remained defiant, and the presiding chief ordered him to be drowned in a nearby river. Even then, the men assigned to the deed tried to let Sabbas go, but Sabbas insisted that they do their duty and not defy their (earthly) lord. And so he was duly drowned, joining more than 300 other Goths known to have died for their Christian faith during two bursts of persecution.

These Gothic Martyrs, who, under most circumstances, would be canonized and held up as examples across the Christian world, have a somewhat complicated legacy that reflects their Arian beliefs, which set them apart from the Roman religious establishment. To this day, modern Catholic and Orthodox Christian authorities recognize some as saints, but not all of them. Ulfilas, most notably, is not Saint Ulfilas, in spite of his accomplishments.

However, arguments over Arianism did nothing to prevent the Romans from using Gothic soldiers. By 295 C.E., and probably earlier, there were Gothic troops among the legions deployed against Persia. They fought under a foedus—an agreement between the Empire and a foreign people.

The Romans used such foedera regularly, as a means to define the terms under which “barbarians” could settle inside the Empire, or trade with or receive aid from it. Foedera were traditionally brokered only with tribes that had been defeated in battle. A universal stipulation was that the tribe in question would provide troops to the perpetually undermanned Roman armies.

Troops serving under a foedus were known as foederati. In the case of the Goths, they always served under Roman officers, rather than under their own leadership (another common stipulation of foedera). The Romans had no interest in ethnically-based power blocs arising within the army. So while Goths could receive promotions and become officers, a separation between them and their enlisted countrymen was usually maintained.

Many Goths took to army, and therefore Roman, life. And as happens in all border regions, cultures began to bleed across the lines drawn on maps. The Goths learned to buy things rather than barter, and returning foederati often sported Roman-style haircuts. By the time of the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy, which ultimately brought Constantine I to power, the Goths were an established part of the geopolitical landscape: Roman Emperors both fought them, and sought their assistance, on either side of the Roman Empire’s borders.

That didn't mean that Gothic raiding stopped. The raids were still a nearly annual occurrence. But the era of mass Gothic invasion and devastation had, for the moment, passed. Prejudice against the Goths remained, however, and would linger as a constant element in Roman society. The feeling was mutual, and anti-Roman sentiment matched anti-Christian fervor in driving the Gothic religious persecutions.

In the interest of moving our narrative along, I’m going to jump a bit ahead, to 366 C.E. and Emperor Valens’ Gothic War—because this allows me to introduce the first two men who stand out in the narrative of the Goths as enduring historical characters.

The first is Athanaric, whom I mentioned briefly in the previous instalment. Athanaric was a chief, having been elected kindins of the Goths’ Thervingian branch with a mandate to lead a unified Gothic response to Valens’ invasion.

The second is Athanaric’s rival chief, Fritigern, who was perhaps miffed at losing the election to kindins, and apparently chafed under Athanaric’s overlordship. According to the sixth-century writer Jordanes, author of The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, Athanaric was of the Balthi clan, whose status among Goths was second only to the Amal clan, and so of higher birth than Fritigern. But one gets the sense that Fritigern felt he was the better man for the job nonetheless.

To explain the war that brought about Athanaric’s election as kindins, I need to back up a bit and provide some background about Roman Imperial politics. The brothers Valentinian and Valens had come to the Imperial throne in 364, with Valentinian ruling the west from Italy, and Valens ruling the east from Constantinople, as per the west-east division that had existed in the Empire since the late third century.

From the start, Valens’ priority had been to shore up the Empire’s defenses against the Persians on the eastern frontier. But the army had its own ideas about where it should be deployed. Everyone knew the Goths were planning a major attack. Why was Valens marching them east?

Meanwhile, back in Constantinople, the eastern Roman capital, an official named Procopius declared himself in insurrection, and quickly took control of the provinces of Asia and Bithynia (then corresponding, respectively, to western and northern portions of modern Turkey). When news reached Valens, he initially considered capitulation, even suicide, but managed to pull himself together and dispatch an army under subordinates to deal with the usurper. Unfortunately, when they reached Constantinople, those men defected.

It took eight months for Valens to get the situation under control, and he eventually defeated Procopius in 366. The usurper was arrested and executed by his own troops after defeat, and his memory was damned.

What does any of that have to do with the Goths? As it happens, Procopius had made contact with the king of the Goths’ Greuthungi branch, Ermanaric, and arranged for the Goths to supply him with troops. The 30,000 Greuthungi troops whom Ermanaric sent south arrived too late to help Procopius, but they invaded Thrace anyway, having come a long way and being not in any mood to return home empty-handed.

Fresh from his defeat of Procopius, Valens continued north, surrounded these rampaging Goths, and forced their surrender. Ermanaric protested, but Valens and his brother, possibly motivated by the anti-Gothic sentiment that was still strong in the Roman army, refused to come to terms. In the spring of 367, Valens crossed the Danube and attacked the Goths in their own territory—even though his new Thervingi targets were distinct from the Greuthungi whom Ermanaric had sent to aid Procopius.

It was this Roman incursion that prompted the aforementioned election of Athanaric as kindins, and so this is where the two strands of our narrative converge.

Athanaric moved to deny Valens any kind of meaningful victory by adopting a fabian approach—withdrawing into the Carpathian mountains with his forces and refusing to fight the Romans directly. Valens rampaged around Wallachia (in modern Romania), burned some easily rebuilt villages, and was eventually forced to leave. Ammianus Marcelinus, the Roman soldier and historian, summed up the campaign dryly: Valens “returned with his men without having suffered any loss, and indeed without having inflicted any.” This could not stand if the honor of the army and the Emperor were to be preserved, but flooding of the Danube prevented Valens from mounting a campaign the following year.

If this all seems like a victory for Athanaric and his Goths, it really wasn’t. Yes, they had avoided defeat in the field. But the Romans had prevented or destroyed the year’s harvests, and the subsequent flooding of the fertile river valleys piled catastrophe on misfortune.

Athanaric would have to make a stand when the Romans returned. And he called for help from Ermanaric and his Greuthungi. They complied. And when Valens crossed the Danube again in 369, his Roman troops met these Greuthungi allies somewhere in modern Moldavia.

The Greuthungi withdrew, but in doing so drew the Romans further into Goth territory, extending their supply lines. At this point, Athanaric accepted battle, somewhere between the Prut and Dniester Rivers. The Goths lost that encounter, but Athanaric managed to maneuver in a way that allowed him to avoid complete destruction. And the frustrated and overextended Romans were forced to come to terms.

Famously, because of his position as kindins of the Goths, Athanaric was forbidden to leave Gothic territory. As noted previously, he and Valens met on a boat in the Danube.

The agreement they reached was decidedly mixed. The former free-trade zone that prevailed along the Danube was restricted to two trading posts, and the Romans ceased paying for foederati troops from the Thervingi. The Goths also handed over hostages, which helped Valens in his bid to declare victory and take on the triumphal title of Gothicus.

The Romans agreed not to interfere in Gothic affairs. And the termination of the foedus left Athanaric with greater manpower to deploy at home in order to deal with internal enemies—which, as he saw it, meant Christians.

Athanaric’s persecution campaign—the second to target Gothic Christians—lasted from 369 to 372 C.E., and was carried out with the co-operation of the same reiks who’d elected him as kindins. This was the persecution in which the aforementioned Saint Sabbas (as he is now remembered by observant Christians) was martyred.

The campaign was connected to the hostility toward Rome that the last decade of deteriorating relations had engendered. Rome had, by now, officially been a Christian entity for over fifty years. Christians were seen by Athanaric and many of his compatriots as a potential fifth column. He feared that the essential nature of the Gothic way of life would be destroyed, and sought to extirpate the threat.

But Athanaric’s persecution succeeded only in deepening divisions within the Thervingi, which his rival Fritigern began to exploit. The post of kindins to which Athanaric had been elected (often translated as “judgeship”) was supposed to have been a time-limited title that expired when the external military threat subsided. But Athnearic now had been kindins for eight years, and it appeared as though he might be looking to make his leadership permanent.

Fritigern contacted Valens in secret, seeking Roman support for a coup against Athanaric. The Emperor was interested. Putting aside his personal irritation with Athanaric, he would have regarded the emergence of a united Gothic monarchy on the Roman doorstep as a horrifying geopolitical prospect.

Valens’ support came at a price, however—and that was Fritigern’s conversion to Christianity. The Gothic leader agreed (rather proving Athanaric’s point about fifth columns in the process). And this horse-trading of faith for power serves to cast Fritigern, perhaps unfairly, as a bit of a slippery character.

I also need to take note here of a fact about Valens that I have not yet mentioned: he was an Arian. This was during the brief window of time in the mid-fourth century when the Arian heresy (as it later came to be condemned) enjoyed imperial Roman support. The result of this historical coincidence was that the Goths’ connection to Arianism, their founding Christian creed, was further strengthened.

In the end, however, whatever plot Fritigern and Valens cooked up ultimately came to nothing—because Athanaric was chosen as kindins again when a new and terrifying threat appeared out of the East: the Huns.

The Huns will be the star of another multi-instalment arc in this series. And so I will confine my treatment of them here to the bare-bones information required to make sense of the Goths’ story.

From the Goths’ perspective, the Huns’ arrival was sudden. They came from East, and the first Goths to face them were the Greuthungi. The doomed fight against these invaders was led by the Greuthungi leader, the aforementioned Ermanaric, who established himself as a hero king in the Germanic saga tradition.

The most sober surviving account of his tragic end is supplied by Ammianus Marcellinus, whose lone mention of Ermanaric in his surviving writings describes “a very warlike prince … his numerous gallant actions of every kind had rendered him formidable to every neighboring nation.”

The story related by Jordanes is more colorful—and that’s the version that found its way into German myths across the continent.

Late in his kingship, Ermanaric had put down a rebellion by a tribe called the Rosomoni (also rendered as Roxolani), but was unable to capture its leader. In frustration, he executed the leader’s wife, a woman named Sunilda, by having her torn apart by horses. Sunilda’s brothers came looking for revenge (a development that one might think Ermanaric would have foreseen). They managed to stab the aging king in the side, but he survived, debilitated by the wound. When the Hunnic assault fell on the Greuthungi, Ermanaric was too weak to muster an effective defense; and though his men fought bravely, they were quickly overwhelmed. The king, distraught at the defeat, and consumed by physical agony, died shortly after the initial attack. (There is a suggestion that he committed ritual suicide—at the improbable age of 110).

Thus did he pass into the oral tradition of the Germans. And variations on Ermanaric’s story appear in the Norwegian Thidreks saga (Þiðreks), the Niebelungenlied, the Old Norse Völsunga saga, and the Edda of Iceland.

For their part, however, the Huns were uninterested in hashing out the literary afterlife of Ermanaric’s death throes. The Greuthungi either surrendered to, or fled from, these marauding invaders, with the terrified survivors bringing news of the cataclysm west to Athanaric and the Thervingi.

The kindins moved quickly. (There was a reason he kept getting elected.) Athanaric gathered an army and positioned it on the west bank of the Dniester River, where he built a Roman-style armed camp. A vanguard force was sent across the river, and proceeded about twenty miles east to observe the Huns’ advance. But the Huns simply went around them, crossing the Dniester on a moonlit night and surprising Athanaric’s main force at its fortified position. “[Athanaric] was stupefied at the suddenness of their onset,” reports Marcelinus. The Gothic commander was able to withdraw with the bulk of his army—he had a talent for that kind of maneuver. But the Huns retained the initiative.

Athanaric regrouped on the plateau between the Prut and Siret Rivers in what is now central Moldova. By this point, he must have been travelling not only with his soldiers, but with their families as well. He set about building what we might imagine to effectively have been an enormous temporary city, or series of temporary towns, presumably mostly tents, behind a long ditch and palisade-type fortification. (The remains of a long wall can still be seen in the region, though archaeologists are divided on whether it’s of Gothic or Roman construction.)

The Huns attacked again before this work could be finished, again from an unexpected direction. The Goths managed to squeak out a draw, and survived—mainly because the Huns seem to have encumbered themselves with war booty.

This latter fact suggests they must have been returning from raids to the southwest of Athanaric’s position, in the Thervingi heartland. It seems that, by this point, the vast majority of the Thervingi were holed up behind Athanaric’s wall, with the Huns looting the countryside at their convenience.

The Goths were left with no way to feed themselves. When Athanaric had fought Valens, he had been able to make a series of tactical retreats, remaining well-supplied in the process until the third year of that war. Against the Huns, however, the Gothic supply line collapsed immediately.

The Hunnic devastation completely kneecapped the Gothic agricultural economy, and whittled the Thervingi options down to an unattractive list. They could stay where they were and starve; they could submit to the Huns and be enslaved; they could fight and probably die; or (spoiler alert) they could abandon their homeland and flee to safe territory controlled by a powerful neighbour.

Athanaric’s prestige was badly damaged by this disastrous turn of events, and Fritigern stepped into the breach. He pointed out that he still had contacts among the Romans. If the Thervingi would follow him, he could negotiate safe passage into the Empire, where they may find protection, food, maybe even land.

Most of the Goths agreed with Fritigern’s plan, and abandoned Athanaric to his fate. They moved south, setting up camp along the Danube River, the border with the Roman Empire. But they couldn’t cross without the permission of the emperor himself.

Athanaric considered following Fritigern, but decided against it. Instead, he and his remaining followers turned west, into the mountains, seeking a place to spend the winter. They pushed up into a valley in the Carpathians, no one knows exactly where, and unceremoniously turfed out the Sarmatian inhabitants. Thanks to the chain reaction set off by the Huns, the tribes that had made up the (largely) peaceful multi-ethnic confederation in the region were now fighting each other for land and survival.

While Athanaric was making his escape, the vast majority of his people, tens of thousands, possibly even a hundred thousand, gathered on the northern shores of the Danube under the leadership of Fritigern. Attempts to cross the river by individuals or small bands were forcibly turned back by the Roman garrisons. And Fritigern didn’t attempt to force the crossing en masse, as such a move would destroy any hope of a satisfactory deal with the Romans.

Unfortunately, any such deal could be made only by the Emperor himself, and Valens was then 1,500 km away, at Antioch. So Fritigern and his chiefs, their subjects, men, women, and children, waited.

In Antioch, Valens’ imperial bureaucrats debated the best course of action. To admit the Goths would put huge strains on the Empire’s resources. On the other hand, the Roman-controlled provinces in the region—Moesia and Thrace (which included parts of modern-day Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey) were still depopulated, and the army undermanned. The Goths could provide a solution to both problems.

On the other other hand, repopulating an area with the Gothic warriors who’d been responsible for this depopulation in the first place would look a lot like foreign conquest with extra steps. Then again, barbarians had been integrated into the imperial structure before. In fact, the assimilation of outsiders was one of the empire’s great strengths. And confidence that the Goths might represent another positive chapter in this trend eventually won the day: Valens sent word to the Danube garrisons to let the Goths cross.

The conditions that Valens set down for this crossing have been lost to history—though it does seem that the deal was different from the kind usually offered to barbarian groups wishing to settle in the Empire.

For one thing, such settlers, who were called coloni, usually were people who’d been defeated in battle, and the ceremony associated with the agreement included their ritual disarmament. Apparently, such an agreement was not in effect in this case, as most of the Goths who crossed the Danube were not disarmed.

In fact, one of Valens’ first communications to the Thervingi was a request for soldiers that he could deploy against Persia. This suggests that these Goths were not considered coloni, whom the emperor could simply have levied at will for use in his legions.

It’s been suggested that the original agreement required the disarmament of the Goths, but the local officials were unable to enforce the requirement under the circumstances. Certainly, those local officials were faced with probably the greatest refugee crisis known to Roman history.

Estimates of the Goths’ numbers vary widely. The Greek historian Eunapius, a near contemporary, reports that there were 200,000 Goths altogether, civilians included. Modern historians cite much smaller numbers. Peter Heather of King’s College London, for instance, suggests 10,000 warriors under Fritigern and 50,000 people in total.

But the Thervingi weren’t the only Gothic group that had fled the Huns to the Danube. A group of Greuthungi under the leadership of a pair of chiefs named Alatheus and Safrax had also arrived, with about an equal number of followers. So that would bring the total number of southbound Goths, of all ages and classes, to between 90,000 and 100,000—all of them crammed up against the river with whatever belongings they could carry, a dwindling supply of food, and the knowledge that the Huns might appear behind them at any moment.

The crossing of the Thervingi was not carried out with what we might imagine to be Roman efficiency. The ferries that regularly carried passengers and goods across the river were insufficient for the task, and the Romans seem to have taken very little care in keeping family or clan groups together, which led to confusion and distress on both banks. Food was being brought in, but there was never enough of it, and what there was passed through the hands of officials who were, let us say, prepared to play favorites.

The opportunities for personal enrichment proved too tempting for the Roman commanders along the Danube frontier to resist. And as they sold food for ever higher prices, desperation mounted. Goths sold themselves or their children into slavery. The most pathetic story concerns the sale of a noble Gothic child in exchange for dog meat. The corruption was great enough to draw subsequent condemnation from almost every source—which is saying something, since this was a world where some baseline level of government corruption was widely seen as part of the pay package.

It was clear that the situation was volatile, and so local troops began to escort groups of arriving Thervingi away from the river. But that created a new problem. The Roman army had been receiving, feeding, organizing, and (in some cases) disarming Thervingi while simultaneously maintaining the border against the still-excluded Greuthungi. It turned out that they did not have the troops necessary to perform all of these duties simultaneously.

Safrax and Alatheus, the Greuthungi leaders, forced their way across the river at this point, and eventually established contact with Fritigern’s camp. The Romans were unable to push the Greuthungi back, and they became a wild card on the south side of the Danube.

For his part, by contrast, Fritigern still wanted to work with the Romans as far as possible. The commander in overall charge of the resettlement project was a Roman named Lupicinus, who’d played a key role in Valens’ defeat of the usurper Procopius. Once the Goths were sufficiently organized, Lupicinus ordered Fritigern to move to the Roman military headquarters at Marcianopolis, which Fritigern did, though progress was slow.

The Goths set up camp outside the walls of the city, whereupon Lupicinus invited Fritigern and a fellow Gothic leader named Alavivus to a feast, an ironing-out-of-differences kind of affair. At least, that’s the most charitable possible reading of Lupicinus’ motives.

What actually happened was that a shoving match broke out between Roman troops and Fritigern’s bodyguards. The noise panicked the already jumpy masses outside the gate, who rioted, and demanded access to Marcianopolis and an opportunity to resupply from the garrison’s food stores. In response, Lupicinus ordered the Gothic leaders’ escort troops cut down. Fritigern managed to slip out of the city, but Alaviv was killed.

Fritigern quickly organized his people into open revolt. They swept out into the countryside, burning and pillaging all across Marcianopolis’ hinterland. Lupicinus raised his troops and set out to stop them, but he was badly defeated by the fed-up Goths just 15 kilometers from his own headquarters.

Fritigern’s rebellion drew in others. A Gothic foederati unit stationed at Adrianople mutinied and joined the Thervingi. Disgruntled miners from across Thrace likewise walked off their jobs to join the rebels; and Fritigern suddenly was enjoying both support and intelligence from local populations that had become disenchanted with their urban Roman (or Roman-allied) persecutors.

The Gothi Minores, Ulfilas’ so-called “little Goths,” however, declined to join the uprising, and, as a result, were driven from their homes. They had to hide in the Balkan mountains while their fellow Goths, the Thervingi, raged across Moesia and Thrace.

Valens refused, even after the defeat of Lupicinus, to take the Gothic threat too seriously; he had, after all, defeated them on their own territory only seven years before. Moreover, he was preparing for war against the Persians and was reluctant to abandon his plans. He did not yet grasp the strategic threat posed by an enemy that, unlike the Persians, was roaming within his own borders.

Ans so the Goths raged at will across the countryside, opposed only by piecemeal local responses. In time, they were further strengthened by the participation of Safrax and Alatheus and their Greuthungian cavalry.

Eventually, Valens pulled himself together and gathered an army in southern Thrace in the Spring of 378 C.E. Fritigern was aware of the emperor’s arrival, and concentrated his forces near the city of Kabile in what is now southeastern Bulgaria. Valens’ intelligence told him that the Goths had only 10,000 men. (I should note here that the Romans were, through most of their history, surprisingly bad at scouting their enemies.)

Further encouraging news for the Romans was en route in the person of the Roman Empire’s western-based co-emperor, Gratian (r. 363-383 C.E.), who was fresh off a successful campaign against the Alemanni on the Upper Rhine, and had already reached the fortified garrison town of Castra Martis, just a few hundred kilometers to the northwest of Valens.

Having decided to seek battle, Valens positioned his army near Adrianople (now the Turkish city of Edirne, lying just across the border from modern Bulgaria), though exactly where is still an open question. After presiding over a council of war, he received an envoy from Fritigern respectfully. But he did not take the ambassador’s message at all seriously.

Fritigern was demanding all of Thrace, including all of its livestock and produce, as federate territory. This was rejected, as the idea of establishing a quasi-independent Gothic state on Constantinople’s doorstep would never be acceptable. In the days before the battle, Fritigern sent at least two other ambassadors. It’s probable that he was playing for time, hoping to gather more men before battle was joined.

The Western Roman Emperor Gratian had not yet arrived with his army. But for Valens, that fact may have argued for haste instead of delay, as he was eager to take solo credit for a victory against the Goths that would be comparable to Gratian’s recent win against the Alemanni.

Valens set out from his camp to meet the Gothic host—a march of more than 15 kilometers in the August heat. As the Romans drew near, the Goths set fire to the grass along the road, so that the legions arrived hot and dehydrated.

As the two armies drew up in formation, one last embassy arrived from Fritigern. This embassy seemed to offer at least some scant promise, as Valens demanded that if Fritigern wanted to talk, he should send suitably high-born representatives. The Goths agreed, on the condition that a noble Roman or two were sent as hostages in return. Flavius Richomeres, a noble in Valens’ party who would eventually serve as Consul, agreed, and was preparing to leave when the whole discussion was rendered irrelevant.

Two Roman units, having become exasperated by the long march, attacked without orders, dragging the rest of the army along with them in a disorganized rush. They were met by the just-arrived cavalry forces of Safrax and Alatheus, who smashed into the Roman right and rolled up the line before breaking off, wheeling round, and doing the same on the left.

Fritigern’s delays had paid off, as the Romans now found themselves fighting a combined Thervingi-Greuthungi force. The current thinking among historians is that the Roman force numbered somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000, with a high of 40,000 being possible; and that Fritigern’s force numbered about 20,000.

Ammianus Marcelinus, writing no more than twenty years after these events, capped his history with an account of the battle. He described the Greuthungi attack as “descending from the mountains like a thunderbolt [to] spread confusion and slaughter among all whom in their rapid charge they came across.”

He describes the bedlam that followed thusly:

And while arms and missiles of all kinds were meeting in fierce conflict, and Bellona [a Roman war goddess] was raging more fiercely than usual to inflict disaster on the Romans, our men began to retreat; but presently, roused by the reproaches of their officers, they made a fresh stand, and the battle increased like a conflagration, terrifying our soldiers, numbers of whom were pierced by strokes from javelins hurled at them, and from arrows. Then the two lines of battle dashed against each other like the rams of ships, and thrusting with all their might, were tossed to and fro ... Our left wing had advanced actually up to [the Goths’ baggage train] with the intent to push on still further if they were properly supported; but they were deserted by the rest of the cavalry, and so pressed upon by the superior numbers of the enemy, they were overwhelmed and beaten down, like the ruin of a vast rampart. Presently, our infantry was also left unsupported, while the different companies became so huddled together that soldier could hardly draw his sword ... And by this time such clouds of dust arose that it was scarcely possible to see the sky, which resounded with horrible cries, and in consequence the darts which were nearing death on every side reached their mark and fell with deadly effect, because no one could see them to guard against them … Amidst all this great tumult ... our infantry was exhausted by toil and danger ... the ground, covered with streams of blood, made their feet slip, so that all they endeavored to do was to sell their lives as dearly as possible ... At last, one black pool of blood disfigured everything, and wherever the eye turned, it could see nothing but piled up heaps of … lifeless corpses trampled on without mercy.

Two thirds of the Roman army was killed at the Battle of Adrianople on August 9, 378 C.E. Among the dead was Valens himself. His body was never found. The result was a crushing blow to the Romans—one seen by later writers as the beginning of the end for the Roman Empire.