Education

History Matters

A restoration of history, in all its complexity, is critical to escaping the polarized, rigid, and often insane political environment we now inhabit.

If history is deprived of the Truth, we are left with nothing but an idle, unprofitable tale.

~Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire

History has moved to the front line of social conflict, but rarely has it been so poorly understood and sketchily taught. After decades of declining interest, only 13 percent of eighth graders achieve proficiency in the subject today. The New York Times reports that “about 40 percent of eighth graders scored ‘below basic’ in U.S. history last year, compared with 34 percent in 2018 and 29 percent in 2014.” This phenomenon can be seen across the West. The study of and interest in the past, noted the Economist in 2019, has largely disappeared in the UK. Study of the 19th century, meanwhile, seems to be vanishing from European classrooms. “We are in danger of mass amnesia, being cut off from knowledge of our own cultural history,” noted the late Jane Jacobs in her 2004 book, Dark Age Ahead. When I show my students a picture of Lenin, barely one-in-ten of them recognize it.

Universities should be beacons of dispassionate learning, so it is particularly unfortunate that they have also been increasingly complicit in obliterating much that is valuable to historical instruction and understanding. In a 2013 article for the Guardian, Ashley Thorne lamented that university curricula were largely ignoring the literary classics. At many US colleges, Thorne noted, books written before 1990 are considered “inaccessible” to students. This breaks a vital link with the past that allows students to identify with their ancestors as part of an ongoing human story, rather than simply dismissing their thoughts and actions as alien, unintelligible, or even intrinsically evil.

The problem is further exacerbated by the much-discussed decline in academic viewpoint diversity, particularly in the social sciences and humanities. The history profession was once famously disputatious, but over the last generation or so, a diminishing number of conservative or even centrist historians has produced monocultural groupthink. A national survey of faculty members from 183 four-year colleges and universities, conducted in 2005, found that liberals were already seven times more numerous across history departments than conservatives. Without the cut-and-thrust of lively historical debate, history risks becoming an ideological discipline, as was the case in the Soviet Union or China today, taught by rote and incapable of generating excitement and interest.

The consequent decline in historical understanding suggests that generations of students will leave higher education ill-prepared to engage or even bother with the past. The 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment found that 86 percent of 15-year-olds are unable to tell the difference between opinion and fact. This lack of preparation empowers propagandists, who often know little about history to start with, to twist the past to suit their own ideological purposes for an equally ignorant audience.

Less remarked upon is the impact that this ignorance can have on how we understand our present and future. An understanding of the past that dwells exclusively on our crimes, mistakes, and failures at the expense of our achievements produces a distorted picture of human potential and an unwarranted sense of despair. This is particularly evident in the pessimism with which younger generations approach issues like race relations, climate change, and the continuing viability of liberal democracy. For if there is no hope to be found in the past, what possible hope can there be for the future?

Race Relations

Critics of traditional history instruction on matters related to race do sometimes raise valid points. Past school curricula distorted history in their own ways, particularly by ignoring the contributions of Asians and Hispanics as well as indigenous groups like Native Americans and Africans. A controversial claim made by one historian in the Washington Post (specifically, that neither Roosevelt nor Churchill opposed Nazism for its commitment to racial supremacy) may have provoked outrage from right-wing pundits, but the point was not entirely misplaced.

Ignorance and the willful politicization of historical debate, however, have also led to some outright fabulism. Vice President Kamala Harris inflamed the dispute over Florida’s history guidelines by falsely alleging that they mandate an outrageously revisionist account of American slavery. The Telegraph recently reported that, at Cambridge, students are being taught that “Anglo Saxons aren’t real” due to the term’s allegedly problematic ethnic connotations. Indigenous leaders in the Commonwealth have recently demanded that King Charles apologize for crimes committed long before he was born. And of course, there are ongoing efforts to redefine July 4th as a moment for national shame and atonement rather than celebration.

Nothing better epitomizes the rise of a new politicized history than the New York Times’ heavily promoted and notoriously tendentious 1619 project. That journalistic endeavor holds that the American War of Independence was largely fought to preserve the colonies’ slave economy. It has since been widely debunked by historians on both the Left and Right. The British, critics point out, did not abolish slavery for a generation after the War of Independence, and the South was no match for the North’s growing industrial economy. The 1619 Project’s premise, as one observer noted, “metamorphosed into a despairing view of the US that has essentially erased the entire abolitionist movement,” not to mention the sacrifices made by hundreds of thousands of union soldiers, both black and white.

None of that prevented the Times from capturing a Pulitzer for its effort. The project’s lead author and curator, Nicole Hannah-Jones, now teaches at the University of North Carolina and has become an iconic figure on college campuses, earning over half-a-million dollars in speaking fees over the past few years. More importantly, an estimated 4,500 schools have since adopted curricula materials related to the Project in the classroom.

Misinforming young people about the past in the name of national denigration is bad enough for its own sake. But historical misinformation is also being transformed into a kind of currency in a contemporary grievance economy—a way of tallying up compensation for past historical wrongs. In the US, this approach is particularly evident in the push for monetary compensation for the descendants of slaves. Last month, California’s Reparations Task Force recommended $800 billion in payments to descendants of slaves resident in the state. Since California was never a slave state, these numbers are based on estimations of discrimination in jobs and housing that occurred more recently. If adopted across the country, the cost of national reparations could top $14 trillion according to advocates.

Besides the financial cost, the notion that history can justify payments to people for crimes committed more than a century ago is both counterproductive and self-defeating. This whole notion of racial justice fails to acknowledge the complex factors that determine how and why the fortunes of groups and individuals fluctuate across time. During the Victorian era, who would have predicted the extraordinary achievements of Asian immigrants across the West? In the worldview of racial radicals, however, everything is the fault of colonialism and European oppression, and as such, constitutes only an outstanding debt.

But the urge to place a dollar price on racial redress is fundamentally flawed. Other considerations such as the decline of the stable family in American life generally, and particularly among blacks, are not allowed to interfere with the preferred narrative of systematic oppression. The call for reparations ignores “socially mediated behavioral issues” in the here and now, notes economist Glenn Loury, and denies people the personal responsibility central to dignity and self-respect. Worst of all, it lays a paternalistic burden of minority salvation on whites, notwithstanding the endemic racism of which they frequently stand accused.

John McWhorter has long argued that other forms of compensation, such as the preferential policies euphemized as “affirmative action,” encourage “therapeutic alienation” among black people and other minorities, leading some of them to adopt a mentality of “anger and scapegoating” instead of doing “the work needed for success.” It is the notion of overcoming, he argues, not dependence, that has led to almost all ethnic progress, whether it has been among Irish, Italians, Jews, Hispanics, West Indians, Asians, or today’s African immigrants.

Rather than exploit history as a means to drain public funds, we can instead learn from the past successes of previous generations who fought for progress in the face of often tremendous odds. It is delusional to deny the enormous expansion of human rights over the past half-century and the gains experienced by most ethnic groups as a result. Reading the ahistorical grievance narrative promoted by progressive activists, one would never know that American blacks now have the lowest unemployment and highest job numbers in their history or that these promising developments may be durable.

History is more than the story of remorseless white oppression—it is a shifting narrative of rising and falling power and changing contingencies. Cruelty has never been the province of one people or civilization. The African monarchs, the Chinese emperors, the Mongol warlords, and the Native American tribes all practiced brutality and mass enslavement of their enemies. At one time or another in their histories, most cultures have had the chance to dominate or have been made to experience domination. As Herodotus, the father of history, noted: “Human prosperity never abides long in one place.”

Climate Change

Widespread concern about the warming of the planet and its potential dangers also needs to be understood in its proper historical context if we are to avoid the existential despair that currently pervades the topic. In his recent book The Earth Transformed, environmental historian Peter Frankopan notes that contemporary warming is “modest in the grand scheme of climate change” and the conditions with which humans have previously had to contend. Human history’s emergence dates from the passing of the aridity of the Ice Age, when some of our forebears may have hibernated through the long brutal winters. The long warming period that followed, notes historian Edward Barbier, ushered in the agricultural revolution at the heart of civilization.

Many factors played a role in shifting climate conditions, including volcanic eruptions, deforestation, and overgrazing, Frankopan notes. Sea level rises and extreme tsunamis have recurred over the centuries as well. Humanity’s best times have generally been when the weather was warm and wet. The Roman warm period, notes Kyle Harper in The Fate of Rome, defined the empire’s remarkable and durable rise. “The climate,” he writes, “was the enabling background of the Roman miracle.” Similarly, empires in the East, such as the Tibetans, rose with favorable weather and declined when things turned drier and cooler.

By 536 BCE, the chronicler Procopius noted that “the sun gave its light without brightness.” This period of cooling helped usher in the Dark Ages, and played a role in the collapse of the Han dynasty as well as political collapses in India and Mesoamerica. The cold weather undermined farming, weakened trade, and made the world’s population more vulnerable to epidemics. Cold weather, dry conditions, and plague, which appeared numerous times in this epoch, created what Frankopan calls a “cocktail of catastrophe.”

But weather patterns change, sometimes for the better. The shift to the medieval warm period in the early years of the new millennium helped to bring about the Renaissance, when populations and agricultural production rose around the world. In contrast, during the ensuing Little Ice Age—traceable to factors like volcanic activity and low sunspot cycles—harvests failed, disease spread, and populations fell. This climate disaster ushered in a particularly bleak and bloody period, which led to starvation and political mayhem in India, Africa, the Americas, and Asia. Europe’s population dropped precipitously, by as much as 30 percent. In A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, Barbara Tuchman writes:

In 1315, after rains so incessant that they were compared to the Biblical flood, crops failed all over Europe, and famine, the dark horseman of the Apocalypse, became familiar to all. The previous rise in population had already exceeded agricultural production leaving people undernourished and more vulnerable to hunger and disease. Reports spread of people eating their own children, of the poor in Poland feeding on hanged bodies taken down from the gibbet.

Yet even in those difficult times, many societies adapted to the changing conditions. Frankopan notes that Chinese farmers developed new technologies to boost yields in the dry northwest, while the importation of hardier plants like potatoes and maize allowed Europeans and Asians to deal with cooling temperatures. Reduced populations spurred high wages and innovations in the more efficient use of horses and plows. Other innovations—from the development of the fur trade and hard liquors—helped people cope with tough conditions.

Similarly, during periods of warming, other measures were needed, particularly to deal with flooding in low-lying areas. In the 13th century, the Dutch responded to rising sea levels by building dykes to hold back rising water. In Volume 3 of his The Perspective of the World series, French historian Fernand Braudel notes that this adaptation to natural challenges created a bountiful agriculture critical to the country’s remarkable global rise. Not surprisingly, the Dutch today are reinforcing their dykes in anticipation of further climate change.

The Dutch example indicates the importance of technology to addressing the challenges we face now. During the Little Ice Age, which started around 1200 and lasted to the 19th century, humans began to find ways to develop new energy, largely derived from coal, and new technologies that allowed them to adapt to unfamiliar climatic conditions. This period saw the publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia Naturalis and the introduction of the scientific method, which the British philosopher A.C. Grayling has called “the birth of the modern mind.”

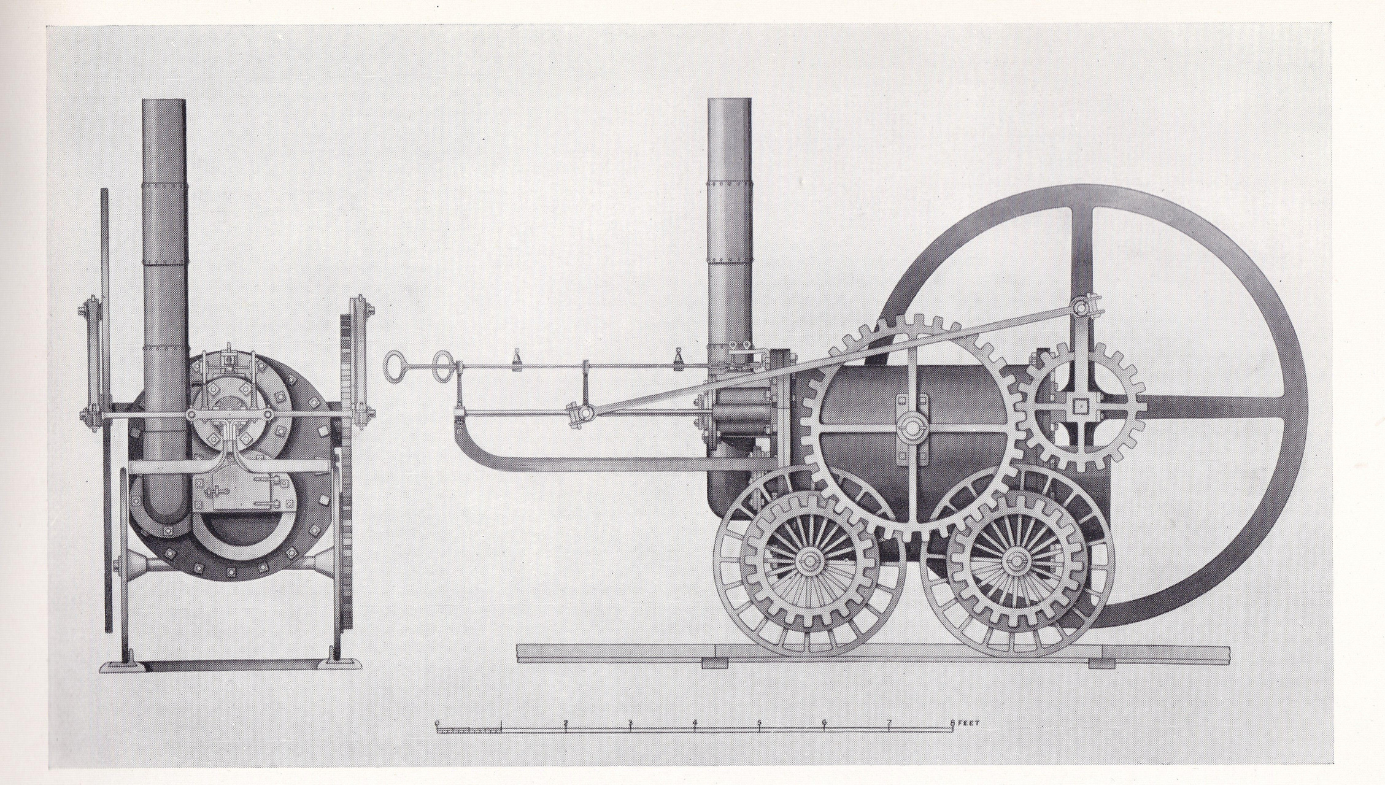

Carbon-based energy—which is still the overwhelming source of all energy used—allowed societies to flourish in cold climates. In Das Kapital, Karl Marx wrote that the steam engine was “the prime mover, whose power was entirely under man’s control.” Humans achieved carbon combustion that would set the stage for exponential growth. As manpower was replaced by machine power, slavery was systemically abolished during the next century.

These lessons from history are fascinating in their own right, but they also offer hope for how human innovation can be harnessed to mitigate risks and solve problems caused by our warming planet today. In 1900, Galveston, Texas, recovered from a devastating hurricane by building a seawall to keep the coastal city safe through numerous major storms over the decades. Now that climate challenges could become more severe, Texas is considering building an even bigger seawall called the Ike Dyke to withstand future storms.

But instead of taking practical steps like these derived from past experience, an ahistorical approach to environmental activism is leaning into fearful catastrophism and lurid predictions of mass starvation and imminent apocalypse. Rather than campaigning to abolish air travel and fight capitalism, activists’ time could be better spent exploring how we might adapt to our changing environment. Given that rising emissions in places like India and China make “net zero” highly unlikely for the foreseeable future, the rational alternative to imposing destructive austerity is learning to reduce emissions while also accommodating changing conditions with innovation.

Defending Democracy

A decay in the teaching of history and civics may help to explain why Millennials, despite their higher rates of university education, are far more likely than previous generations to be dismissive of basic constitutional and civil rights. Many, as I indicated above, tend to know little to nothing about the Soviet Union or the history of totalitarian communism. Some 40 percent of Millennials, notes the Pew Research Center, favor suppressing speech deemed offensive to minorities—well above the 27 percent among Gen-Xers, 24 percent among Baby Boomers, and only 12 percent among the oldest cohorts, many of whom remember the fascist and communist regimes of the past. Nearly 30 percent of people under 30 even think it’s okay to have cameras in every home.

Similarly, European Millennials, like their counterparts elsewhere, display far less faith in democracy and fewer objections to autocratic government than previous generations, according to a 2020 University of Cambridge report. Confidence in basic institutions, science, and capitalism in particular are at historically low levels both in the US and in the UK. History helps to provide us with a sense of perspective and a reminder of the value of liberal democracy and of the freedoms and protections it enshrines. It can also provide us with cautionary tales about its fragility.

The West’s understandable excitement after the fall of the Soviet Union led many to embrace the idea that an “arc of history” was curving toward a permanent global ascendancy of liberal economic and cultural attitudes embraced by the Right and Left. In our enthusiasm, however, we may have been too dismissive of the role of historical memory. Distinguished commentators like Francis Fukuyama, Thomas Friedman, and Kenichi Ohmae all wrote books in which they envisioned an era where even countries like Russia and China would shift in a democratic direction. But Ohmae’s 20-year-old notion of the Triad—a world controlled by a concert of enlightened governments in North America, Europe, and Japan—has not exactly come to pass. Fukuyama’s celebration of “the good news” of democracy’s inevitable spread, and his insistence that tech growth favors “a universal evolution in the direction of capitalism” now look dated to many realists and progressives.

Perhaps more accurate was the vision laid out in Samuel Huntington’s 2011 book, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Huntington predicted the Ukrainian conflict as well the resurgence, at the expense of the West, of many cultures—Indian, Chinese, Arab, Turkish—that had suffered a steep decline during the period of European predominance. Power, Huntington predicted, would shift from Western to non-Western countries. Rather than a world shaped by the logic of markets and the rule of law, we are now seeing the ascendency of autocrats and intensifying tribalization. In other parts of the world, primitivist religious urges have reasserted themselves.

Of course, the final resolution of the current global crisis may yet prove the optimists correct. Some, including Fukuyama, suggest that the stronger-than-anticipated Western support for Ukraine demonstrates the global vitality of liberal democracy. The “arc of history,” he maintains, still bends towards liberal democracy. Yet the ghost of Huntington looms large, as much of the developing world, including emerging superpowers like India, eschew the anti-Russian crusade while building up a Hindu-led quasi-religious state. What is certain is that the defense of democracy at home and abroad depends upon an historical understanding of its value despite its manifest flaws, and upon an appreciation of how much worse the theocratic and authoritarian alternatives have proved to be, despite the idealism of their rhetoric.

History’s Call: For Reason and Moderation

The ignorance and political instrumentalization of history has helped to turn a discipline intended as a method of discovery into another front in the ideological struggle between progressives and conservatives. As we can see in Florida and elsewhere, the Right can prove as censorious as the Left. There is also a gulf between older liberals, who still believe in America’s system and its capacity for reform, and younger progressives, who see the whole national project as rotten in the core. The old liberals, and their generally less doctrinaire view of history, seem to be on their way out.

“The most effective way to destroy people,” noted George Orwell, “is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” This was particularly evident in the Soviet Union, where proletarian writers called on the state, as one put it, “to destroy the museums, crush the flowers of art.” Even late Soviet textbooks insisted that South Korea and the US, not Kim Il Sung, started the Korean war. In today’s Russia, history continues to be misrepresented in order to foreground the growing emphasis on Orthodoxy and traditional imperialism required by the current regime. This approach also characterized education under National Socialism. As historian Klaus Fischer notes in his book Nazi Germany: A New History, German history was “blatantly distorted to fit the National Socialist mold.”

Today, we are faced with our own catastrophic cocktail of general ignorance and a drive for indoctrination. Maybe we won’t quite see a reprise of the early Middle Ages, when “the very mind of man was going through degeneration,” as Henri Pirenne once put it. But we could be creating what Roderick Seidenberg called “post-historic man,” cut off from the traditions and values of our civilizational past

A restoration of history, in all its complexity, is critical to escaping the polarized, rigid, and often insane political environment we now inhabit. The past provides warnings but also the inspiration needed to fend off despair. We have overcome challenges in the past and we can do so again, no matter how daunting things may seem. This hope is in desperately short supply among a distressed and anxious new generation.

Historical knowledge is fundamental to achieving a better future. The Renaissance provides a clear precedent for this. The efflorescence of that period emerged in large part from the rediscovery of classical civilization. Humanism, which shaped our modern world, challenged the prevailing religious dogmas. This rediscovery of the classical past, notes the late historian Paul Johnson, was critical to the ascendancy of first Venice then Amsterdam, followed by London and New York. It provided the springboard for our own often chaotic but nevertheless tangible progress over the past 500 years.

Rediscovering our history of achievement and seeking to improve upon it are critical if that history is to inform new generations, just as it did in Italy nearly a millennium ago. Recovering and embracing the past in all its complexity is our special gift to posterity.