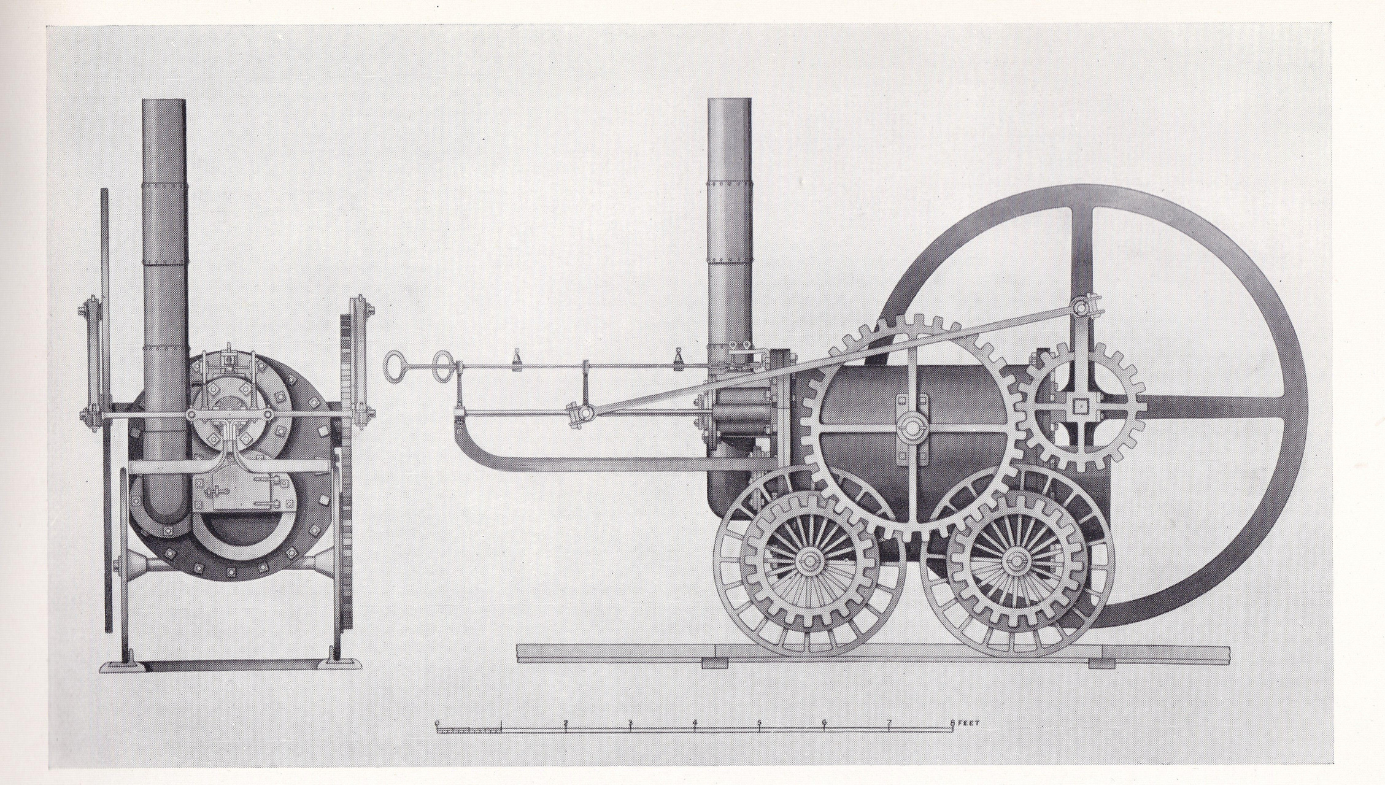

In March, Britain’s Daily Telegraph and GB News channel both reported that the National Museum of Wales would be relabelling a replica of the first steam-powered locomotive, unveiled by its Cornish inventor Richard Trevithick in 1804. Trevithick had no links to slavery, but the amendment has apparently been included anyway as part of the museum’s commitment to “decolonizing” its collection. In a statement defending what it described as the addition of “historical context,” the museum said: “Although there might not be direct links between the Trevithick locomotive and the slave trade, we acknowledge the reality that links to slavery are woven into the warp and weft of Welsh society.” The statement continued:

Trade and colonial exploitation were embedded in Wales’ economy and society and were fundamental to Wales’ development as an industrialised nation. As we continue to audit the collection, we will explore how the slave trade linked and fed into the development of the steam and railway infrastructure in Wales.

In a similar vein, back in 2014, MSNBC broadcaster Chris Hayes wrote an article for the Nation in which he drew a rather tenuous connection between human slavery—specifically, the kind practiced in the US prior to 1865—and the use of fossil fuels. Hayes argued that the reluctance of energy companies and their investors to forfeit the financial value of their fossil-fuel assets is analogous to the reluctance of pre-Civil-War southern slaveholders to surrender the financial value of their human “property.” He went on to assert that environmentalists attacking the use of fossil fuels are in a moral and tactical position similar to that of the pre-war Abolitionists.

This whole line of thinking reminds me of a few things:

1) Shortly after obtaining his freedom, former slave Frederick Douglass visited a shipyard in New Bedford, where he observed the cargo being unloaded. In his memoir, My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass wrote:

In a southern port, twenty or thirty hands would have been employed to do what five or six did here, with the aid of a single ox attached to the end of a fall. Main strength, unassisted by skill, is slavery’s method of labor. An old ox, worth eighty dollars, was doing, in New Bedford, what would have required fifteen thousand dollars worth of human bones and muscles to have performed in a southern port.

2) Sometime around 1900, a young PR man recently hired by General Electric in Schenectady realized he had a problem. He had obtained his job with glowing promises of all the great press coverage he would generate for the company. But now his boss wanted him to place “a terrific front-page story” about a 60,000-kilowatt turbine generator that the company had just sold to Commonwealth Edison. The PR man knew that such a story would only merit a paragraph on the financial pages, so he went to see GE’s legendary research genius Charles Steinmetz for advice. Headlines, he explained, need drama, and “there’s nothing dramatic about a generator.”

Following a quick calculation, Steinmetz determined that this particular machine could perform the physical work of 5.4 million men. The slave population in the US on the eve of the Civil War had been 4.7 million. “I suggest,” Steinmetz told the young PR man, “you send out a story that says we are building a single machine that, through the miracle of electricity, will each day do more work than the combined slave population of the nation at the time of the Civil War.”

3) Owen Young was a farm boy who grew up to become the Chairman of General Electric. Young’s biographer Ida Tarbell offers this description of what life had been like for a farm wife on “wash day” back then:

[Young] drew from his memory a vivid picture of its miseries: the milk coming into the house from the barn; the skimming to be done; the pans and buckets to be washed; the churn waiting attention; the wash boiler on the stove while the wash tub and its back-breaking device, the washboard, stood by; the kitchen full of steam; hungry men at the door anxious to get at the day’s work and one pale, tired, and discouraged woman in the midst of this confusion.

Hayes does not seem to understand—or at least, he was reluctant to recognize—that the benefits of an energy source accrue not only to the companies and individuals who develop and own that energy source, but also to the people of the society at large. The benefits of the coal and oil (and later natural gas) burned to power the turbines made by Owen Young’s company did not go only to the resource owners and to GE and the utility companies, but also to the farm housewives with whom he had grown up.

4) Fanny Kemble (1809–1893) was a famous British actress who was also an avid diarist and a brilliant social observer. In 1830, she became one of the first people to ride on the newly constructed London-to-Manchester railway line. Her escort on the trip was none other than George Stephenson, the self-taught engineer who had been the driving force behind the line’s construction. She noted that the British government had rejected Stephenson’s railroad plans on grounds of unfeasibility, but added:

The Liverpool merchants, whose far-sighted self-interest prompted them to wise liberality, had accepted the risk of George Stephenson’s magnificent experiment, which the committee of inquiry of the House of Commons had rejected for the government. These men, of less intellectual culture than the Parliament members, had the adventurous imagination proper to great speculators, which is the poetry of the counting-house and wharf, and were better able to receive the enthusiastic infection of the great projector’s sanguine hope than the Westminster committee.

She contrasted the character of men such as Stephenson with that of the aristocracy, as represented by Lord Alvanley in particular: “I would rather pass a day with Stephenson than with Lord Alvanley, though the one is a coal-digger by birth, who occasionally murders the King’s English, and the other is the keenest wit and one of the finest gentlemen about town.”

Kemble had a bit of a crush on Stephenson, to whom she referred as “the master of all these marvels, with whom I am most horribly in love.” Nevertheless, industrialization—Trevithick’s locomotive, Stephenson’s railway, and the steam engine itself (which Boris Johnson once called a “doomsday machine”)—enabled self-made men like Stephenson to gain influence they never could have had in a pre-industrial society, and that this reduced the relative power of the Lord Alvanleys. Aristocrats and would-be aristocrats have tended to disapprove of technologies which enable physical and social mobility. The railroads, Lord Wellington fretted, would “encourage the common people to move about needlessly.”

If I had to guess, I’d say the people who run institutions like the National Museum of Wales are generally more like the Alvanelys of the world than the Stephensons (although perhaps without the wit for which Alvanley was renowned). In any event, the historical timeline suggests that the sailing ship, the cannon, and the instruments and mathematics of celestial navigation were more obviously enablers of the slavery and colonial expansion than Trevithick’s locomotive. But such a link fails to combine the anti-racist lesson with an environmentalist one. In fact, the human use of the horse likely did more to aid colonial conquest, since it enabled the use of chariots and mounted cavalry. Not to mention all forms of metalworking, from bronze to steel.

When a society compulsively disrespects its historical accomplishments—when it obsessively seeks to turn every good thing into a bad thing—the outlook for that society is bleak. It destroys social cohesion, and sends the wrong kind of message to actual and potential opponents. The matter of the steam locomotive display in Wales may seem minor, and certainly trivial when compared with the appalling events in Ukraine or the threat of Iranian nuclear weapons. But it is not.

The behavior of the museum administrators in Wales is of a piece with other contemporary symptoms, such as the eagerness within influential circles in the US to embrace the conclusions of the New York Times’s revisionist 1619 project. It is part of the politicization of everything. Science, technology, and art cannot—indeed, must not—be appreciated simply on the grounds of beauty, utility, or truth; everything must be reduced to race, gender, and other academically and media-approved categories of analysis.

Trends such as these have real-world implications, including the growth and decline of nations and their relative power. Writing in 1940, C.S. Lewis, warned about the dangers of what he called the National Repentance Movement, which focused on the need to apologize for Britain’s sins (thought to include the Treaty of Versailles) and to forgive Britain’s enemies.

Certainly, the British State had done many bad things during its long and eventful history—as well as many good things. But the excessive focus on its sins was part of a phenomenon manifested in a 1933 motion debated at the Oxford Union: “This House will under no circumstances fight for King and country.” To the Nazis and the Imperial Japanese, attitudes like these indicated that aggression would not meet much resistance. They also informed a policy of appeasement.

Liberals and progressives (as they call themselves) claim to be greatly concerned with physical sustainability of resources and ecosystems. But they are too eager to undercut the social sustainability of their own societies and the physical infrastructures on which those societies depend, however fond they may be of repeating the word “infrastructure.”