Quillette Cetera

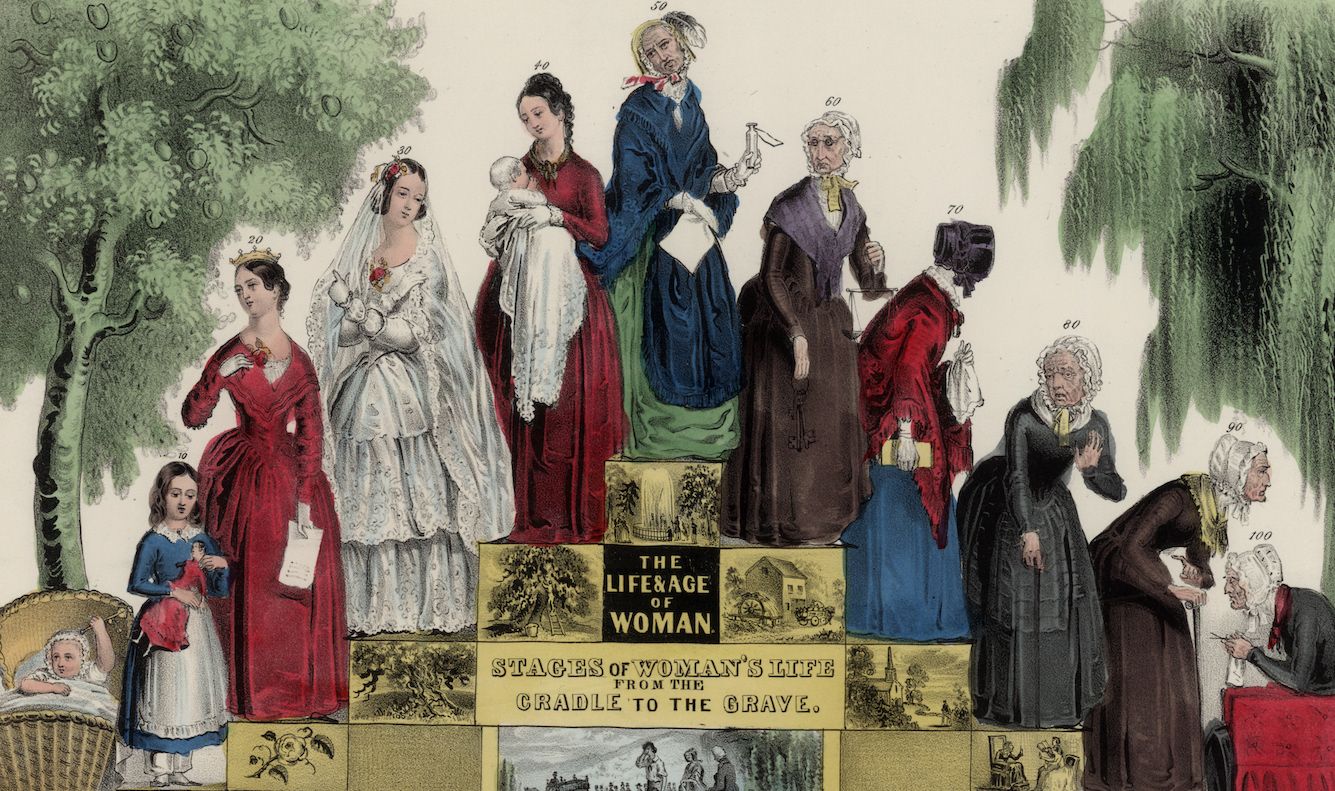

What Is a Woman? Many Philosophers (Still) Aren’t Allowed to Say

An Oxford-based academic philosopher explains why he no longer uses a pseudonym when discussing plain truths about biological sex.

Debates on sex and gender have suffered from a want of moral and intellectual toughness. More detailed, less question-begging diagnoses are possible of why so many smart people shy away from publicly acknowledging that a woman is an adult human female. But there has been a gross failure of nerve. Most of the men known as “trans women” are sex-typical adult human males. Yet despite this obvious fact—and many such men’s well-documented sexual arousal at pretending to be female—much of the intelligent world has allowed itself to be bullied into treating them as counterexamples to the generalisation that women are female. To my disappointment, this pattern has been on display in my own field, academic philosophy.

In May 2023, Quillette published an article I wrote about the cancellation of MIT philosopher Alex Byrne’s book, Trouble with Gender, which had been under contract with Oxford University Press, before being rejected for spurious reasons; and the reaction to the news among philosophers. At the time, I was feeling more frustrated than tough. Indeed, I was not very tough about it at all; as I hid behind a pseudonym (“Thomas Palmer”) when I published my Quillette article.

More recently, however, I have written a review essay on Trouble with Gender, this time under my own name, for The Philosophers’ Magazine (TPM). The consideration that tilted the balance was not that I was hired to a safe academic position. I was not. Rather, it was that almost no philosopher in a safe academic position has spoken up in defence of a sex-based understanding of what it is to be a woman.

Certainly, other philosophers have emphasised the moral importance of sex, such as Holly Lawford-Smith and Kathleen Stock. Both were swiftly vilified. An open letter by self-described “members of the international scholarly community” accused Lawford-Smith of “mobiliz[ing] transphobic bigotry and rhetoric.” And Stock was hounded out of the University of Sussex in 2021 as a result of her expressed views (including those she’d been expressing in Quillette since 2019). With such scant exceptions, academic philosophers have almost uniformly acquiesced in a cultural taboo on recognising the central role of sex in humans’ cognitive and practical lives.

It was in part due to my willingness to write such an essay that TPM’s publisher, Jeremy Stangroom, recently appointed me as the new editor; on the basis that it signalled my commitment to publishing a plurality of perspectives, as per TPM’s longstanding policy. This was an unexpected reward. One lesson here is that it is hard to predict what piece of writing will carry benefits.

More generally, I believe that philosophers are likely underestimating the collective cost to their field of failing to use their intelligence and expertise to combat philosophical errors about sex and gender. It makes the discipline look weak—a perception that sceptics of philosophy will be only too happy to invoke when dismissing the value of philosophical enquiry.

In any case, there is a pleasure in not compromising on one’s knowledge. I recommend it.