Art and Culture

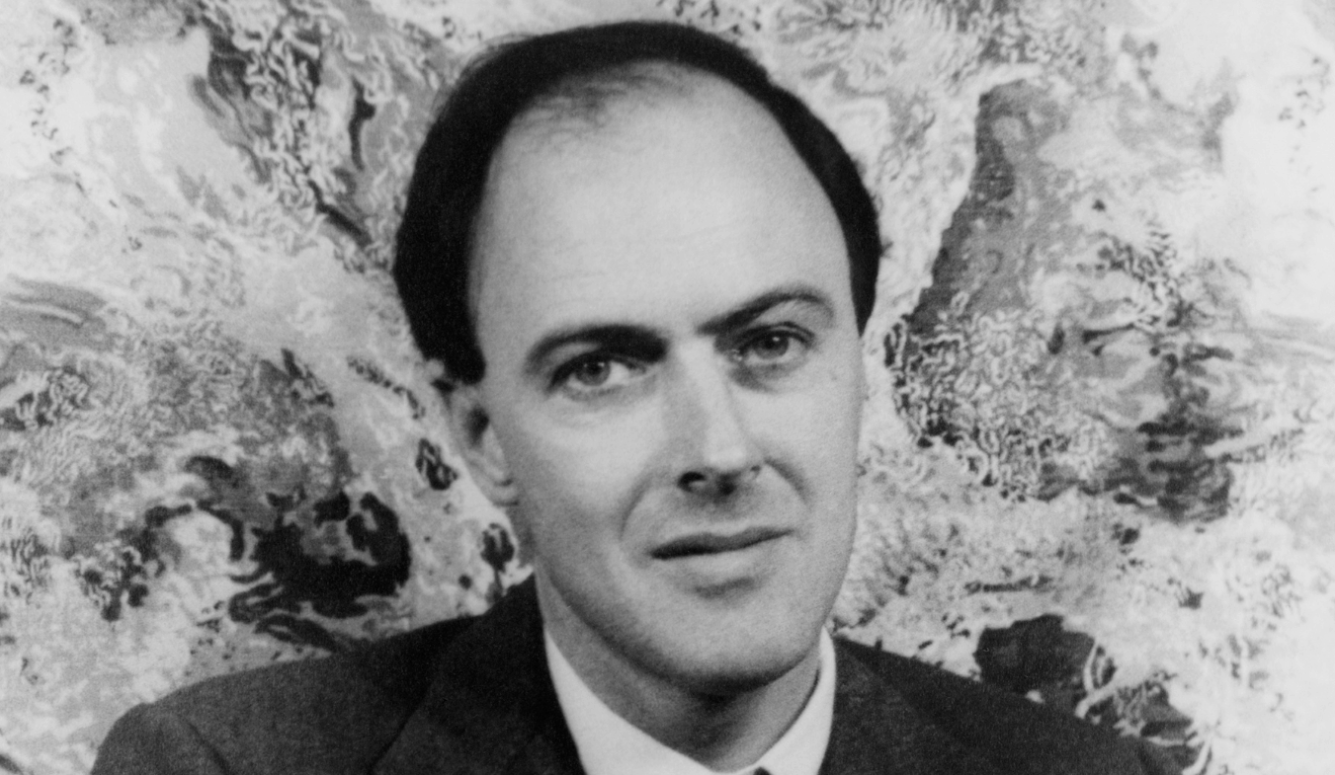

Roald Dahl’s Forgotten Novel, 75 Years On

Before finding fame as a children’s author, Dahl penned the first novel on nuclear war to be published after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Setsuko Nakamura was 13 years old when the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima. She remembers seeing “a blinding bluish-white flash” and then “having the sensation of floating” as the building around her collapsed. When she regained consciousness, she heard the faint cries of her classmates, trapped in the burning ruins: “Mother, help me. God, help me.” Three hundred and fifty-one of her schoolmates died—just a fraction of the overall death toll, which is estimated at anywhere from 70,000 to 140,000.

On the other side of the world, in the nation that launched the attack, the human impact of the atomic bomb was not widely understood at the time. The US imposed strict censorship, confiscating medical reports and photographs from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and restricting the publication of survivor accounts. In any case, the American public was more in the mood for jubilation, as the bombings brought an end to almost four years of war with Japan.

Only a few citizens truly understood the destructive power of this new weapon and the existential threat it posed to humanity. Among them was a 28-year-old flight lieutenant named Roald Dahl, stationed at the British Embassy in Washington, DC. Rather than celebrating the end of the war, this young man fell into a deep despair at the prospect of what he believed was an inevitable nuclear apocalypse. His letters of the time abound with this fear, and he even wrote a short story in which nuclear bombs are planted in cities across America. Though this story was never published, he would later become a household name thanks to his incredible success as a children’s writer. But the circumstances that had brought him to Washington were already as extraordinary as anything in those fantastical tales for which he would become famous.

Dahl grew up in English boarding schools, where he survived deadly disease outbreaks, a fire in his boarding house, and military exercises with live ammunition. He then moved to Tanzania to work for Shell. When the Second World War broke out, he trained as a pilot, only to crash-land on his first day of active service. He recovered from his injuries long enough to achieve five confirmed kills over Greece and Palestine, before being sent to Washington. He quickly assimilated into American high society, staying in the White House with President Roosevelt, embarking on an affair with French actress Anabella, and getting his start as a writer through a connection to C.S. Forester, author of the Horatio Hornblower novels. Most remarkably of all, he was commissioned by Walt Disney to write an animated film, based on the Royal Air Force myth of the gremlins, impish beings who were said to cause mechanical mischief aboard military aircraft. Though the film was never completed, Disney published Dahl’s story as a children’s picture book in 1943, with the gremlins presented as cute creatures who are persuaded to repair aircraft, rather than destroy them, as part of a fight against the common enemy of the Nazis.

After the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Dahl became obsessed with the idea of an imminent Third World War and certain nuclear holocaust. And so, when the gremlins re-entered his creative consciousness, he transformed them from the sweet Disneyfied figures of his picture book into something more sinister—a race of hideous subterranean beings, gleefully waiting for humanity’s self-destruction. These newly imagined gremlins would become the central figures of Dahl’s first novel, Some Time Never, a pacifist fable on the subject of nuclear war. Published in 1948, the novel failed to impress readers or critics and soon sank into obscurity. It can be said to have set back Dahl’s career as a writer, forcing him to reinvent himself, first as a “Master of the Macabre” with his adult short stories in the 1950s, and later as a children’s writer from the 1960s on.

Some Time Never celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, but it has never been reprinted despite Dahl’s subsequent worldwide fame. This overlooked novel deserves greater attention, due to its historic importance within the literature of nuclear war. In his biography of Dahl, Jeremy Treglown describes Some Time Never as “the first novel about nuclear war to appear in the United States after Hiroshima.” Dahl’s authorised biographer, Donald Sturrock, goes a step further, calling it, “the first published novel about the atomic bomb.”

Such claims are difficult to confirm, but Dahl was certainly one of the first writers to take nuclear war as the central theme of a novel. Before Dahl, the topic had largely been confined to science fiction short stories, published in the pages of Astounding and other pulp magazines. And while other novels had featured nuclear weapons, they had often used them as a plot device, rather than seriously engaging with questions of nuclear annihilation. For example, the 1946 novel Mr. Adam tells the story of an explosion at a nuclear weapons plant, which causes all men on Earth to become sterile, except one, who must now repopulate the human race. Another example, The Murder of the U.S.A., also from 1946, uses nuclear weapons to create a new twist on the mystery novel—rather than identifying an individual murderer, this mystery aims to uncover which nation is guilty of launching a surprise attack on the US.

A less frivolous example of a postwar book on nuclear conflict is World Aflame: The Russian-American War of 1950. Published in 1947, this short account details an imagined war between the two superpowers, written in the style of a report from a newsman. Though it predates Dahl’s Some Time Never by one year, it is less a novelistic work, and more a carefully researched work of speculation, aimed at galvanising antiwar advocacy.

Whether Dahl’s biographers are correct to identify him as the “first” writer to address nuclear war in a novel, he certainly was ahead of his time by any account. Indeed, though his fame was to come later, he is one of the only novelists of renown to tackle the subject in the immediate postwar period. The only other example might be Aldous Huxley, best known as the author of Brave New World, whose novel Ape and Essence appeared a few months after Dahl’s and imagined a postapocalyptic world devastated by “the Thing”—a combination of atomic and biological warfare.

Dahl seems to have been aware of his foresight in taking nuclear war as a literary theme and he had high aspirations for his debut novel. The dust jacket describes the book as having a “Swiftian quality,” invoking the name of Jonathan Swift, whose 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels used fantastical elements to satirise attitudes of the time. Dahl’s authorised biographer, Donald Sturrock, believes this comparison is an accurate reflection of Dahl’s high-minded ambitions. “I think he wanted to be a satirist like Jonathan Swift,” Sturrock remarked in a 2016 interview. “I think it’s the way he would like to have gone had his career as a novelist taken off the way he wanted it to.”

Another major influence from the literary elite was John Hersey, a journalist who wrote the first major account of the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombings for American audiences. Published a year after the attack, it took up an entire issue of the New Yorker and caused a sensation. “My God I wish I had gone to Hiroshima to do what Hersey did,” Dahl remarked in a letter to his agent towards the end of 1946.

Dahl’s lofty literary aspirations certainly seemed founded. Some Time Never was brought to publisher Scribner’s at the personal request of Max Perkins, perhaps the most famous editor in the history of American literature, best known for his association with F. Scott Fitzgerald. However, Perkins died just two days after receiving Dahl’s manuscript. Years later, Dahl would reflect on this misfortune as a major reason for the novel’s failure. “It was going to be a good book, thanks to Max,” Dahl said in 1981. “But one week after I delivered the manuscript, he died.”

This statement is uncharacteristically generous of Dahl, acknowledging a fundamental truth about his writing—that it often benefitted from editorial input. One example is his children’s book Fantastic Mr. Fox, published in 1970. In the story, the title character is trapped in his foxhole by three malicious farmers, who plan to guard the entrance until he starves to death. In Dahl’s original draft, Mr Fox survives by burrowing underground to a nearby supermarket to steal food from the shelves. It was editor Fabio Coen who suggested that the story would have more of a sense of justice if Mr Fox stole from his prosecutors by burrowing into the storehouses of the three farmers. Dahl admitted that Coen’s suggestions were “so good that I feel almost as though I am committing plagiarism in accepting them.”

Dahl benefitted even more from editorial inputs in the 1980s (perhaps his most successful and productive period). During that decade, his editor Stephen Roxburgh wrote entire passages of dialogue that were incorporated word for word into The BFG. He suggested new plot elements for The Witches and also had Dahl swap the protagonist for another character. And, he played a key role in structuring Dahl’s autobiographical works Boy and Going Solo, transforming them from a loose collection of anecdotes into a coherent story. Dahl was so impressed with Roxburgh’s work that he nicknamed him Max Perkins.

Unfortunately, in 1947, when the real Max Perkins was needed to edit Some Time Never, Dahl was left on his own. In fact, Perkins’s unexpected death created such a backlog of work at Scribner’s that the manuscript was barely touched by any editorial hands. The absence of editorial input in Some Time Never shows. The book is a curious blend of the horrific and the juvenile. As Jeremy Treglown put it in his biography of Dahl, “The book can’t decide whether it is for adults or for children.”

The novel’s greatest issues are structural. It is split into two parts, the first of which follows a group of Royal Air Force pilots during the Battle of Britain. It details the sudden emergence of the gremlins, a wicked race of diminutive creatures who hide aboard British aircraft and interfere with the machines mid-flight. This section of the novel is repetitious, with several chapters following the same structure: a pilot goes out on a mission, is sabotaged by gremlins, manages to return to base, and regales his fellow officers with stories of what he has seen.

In the second half of the novel, the perspective shifts radically. Each of the pilot characters is immediately abandoned in a chapter describing the nuclear destruction of London. From there, the novel moves underground into the lair of the gremlins, who, having learned of the existence of nuclear weapons, decide to wait until humanity destroys itself, before emerging to claim the planet for themselves.

This bizarre structure renders the entire first half redundant, as the aircraft sabotage of the gremlins has no consequence or bearing upon the rest of the novel. Furthermore, by turning the gremlins into passive agents, the second part of the novel becomes a story with no action. We simply follow the reports of the gremlin scouts as they check in on the status of mankind’s self-destruction in the Third World War and later the Fourth World War. Among the gremlins, there are no named characters. Only the gremlin leader might be said to be a distinct individual—his role consists largely of making speeches on the nature of the human, “a brainy creature whose brain is great enough only to plot his own destruction, but not so great that it can save him from himself.” But Dahl’s moralising is undercut by the absurdity of the gremlins, who wear green bowler hats and knee-high boots and sing silly songs about snozzberries, a fruit that forms the cornerstone of their diet:

They are clustering thick and they’re ready to pick—

If we hurry just think what there’ll be:

There’ll be lashings of wonderful snozzberry pie

And snozzberry jam for tea!

Even before the book was published, Dahl was beginning to have doubts about it. Sturrock senses “uncertainty and nervousness” in Dahl’s letters of the period, noting that his correspondence with his agent and publisher “seem to invite comment and criticism.” At other times, Dahl was more direct: in a letter to his friend Charles Marsh, he referred to Some Time Never as the “bastard book.”

After the novel was published in April 1948, Dahl immediately began to distance himself from it. He complained to his agent that, “No-one I’ve given it to so far likes it” and observed that every review “stinks to high heaven.” But Dahl is exaggerating—it would be more accurate to say that the reviews were mixed. Even those that were critical noted the importance of the subject matter Dahl was attempting to tackle. For instance, the New York Times acknowledged that the novel “says important things, but they could have been said with less repetition, less preliminary build-up and fewer words”—a clear indication of the need for editorial input. Meanwhile, the Saturday Review focused on the strange contrast between the novel’s moments of realism and its moments of fantasy. “The non-fantasy parts can stand securely on their own high merits,” the reviewer suggested, arguing that Dahl’s chapter describing the atomic blitz of London was “far more terrifying than all the Gremlins,” which he found “simply aren’t in any way convincing.”

One of the more positive notices was a short piece in the British fanzine Fantasy Review—perhaps indicative of the fact that nuclear war was still considered a topic of science fiction at the time. Here, the novel was described as “very credible” and “deliciously satirical.” However, if he had read this review, Dahl might have been aggrieved to find himself described as more “Shaverian” than Swiftian, a reference to Richard Shaver, an American science-fiction writer who claimed to have personally visited a secret underground civilisation and based his stories on these supposedly true encounters.

Perhaps the most positive review appeared in the Glasgow Herald, following the book’s UK publication in 1949. Dahl’s novel was described as “outstanding,” “highly original,” and “hugely entertaining.” But by this point, Dahl had moved on. In 1950, he wrote to his editor on the progress of a new novel (which would never be published), contrasting it with Some Time Never: “No more satiric or metaphysical bullshit like Gremlins. Just ordinary stuff.”

In later years, Dahl would reflect on Some Time Never even more negatively. When a fan wrote to him in 1971 asking where she could find a copy of the out-of-print book, Dahl simply responded: “It’s not worth reading.” And when the idea of reprinting the novel in paperback was broached, he immediately quashed it: “Why in God’s world anybody should want to paperback that ghastly book I don’t know.”

But although Some Time Never didn’t achieve Dahl’s high-minded ambitions, the novel does have a few moments of greatness, and showcases some of Dahl’s burgeoning skill as a young writer. For instance, despite their irrelevance to the novel’s central plot, the flying sequences of the first part are beautifully written—typical of Dahl’s early work, which was often inspired by his experiences as a fighter pilot. The most effective is a scene in which Dahl describes a kind of overview effect caused by the perspective of seeing Earth from high above: “probably the height and speed at which one flew had a great deal to do with the manufacture of strange thoughts and feelings.” Observing the smallness of the people and planet below leads to a nihilistic conclusion in the minds of the pilots: “the sum total of all things, of living, loving, hating, dying, adds up, when the sum is carefully done, to nothing, to precisely nothing.”

One is reminded of this in the second part of the novel, when Dahl describes the temptation a world leader must feel with his fingers on the nuclear launch buttons: “Just imagine how he must continually be running the tips of his fingers lightly over their smooth surfaces, longing, longing, absolutely longing to give one of them just one tiny little press.” Just like the pilots, those with the power to launch the destructive power of nuclear weapons also experience a kind of overview effect, seeing human beings from a distance so great that they become mere numbers on a military scoresheet.

Dahl’s conception of a nuclear launch mechanism is also worth mentioning, as it predated the real-world creation of the intercontinental ballistic missile by almost a decade. He shows equal prescience in his imagining of “pilotless planes,” a fictional precursor to today’s military drones, which Dahl imagines as weapons for biological warfare. However, the most remarkable achievement in Some Time Never is the chapter on the nuclear destruction of London. Dahl is clearly indebted to John Hersey for this chapter, borrowing from the survivor’s accounts he gathered in Hiroshima. But by transplanting the devastation to a location more familiar to Western readers, Dahl brings the destructive power of nuclear weaponry closer to home and creates a horrifying portrait of what a nuclear strike on the UK capital could realistically look like.

Just as Hersey shifts from the perspectives of different survivors at the moment the bomb hit Hiroshima, Dahl provides us with a viewpoint of the detonation from three of his pilot characters. One dies immediately, another suffers from his burns for an hour before perishing, and a third survives the initial blast, thanks to being on the Underground transit system at the time. Dahl’s descriptions of the carnage they experience are imbued with a powerful realism, skilfully adapting imagery from Hersey’s account. Where Hersey describes how a woman’s “skin slipped off in huge, glove-like pieces,” Dahl has one of his characters feel his “skin coming away like damp paper from the flesh.” And, where Hersey provides the image of “the man whose burned face was scarcely a face any more,” Dahl goes into even more graphic detail, describing the “melted flesh upon the face, the empty eyes, the hair burnt off.”

Although Dahl’s is a work of fiction, one never has the sense that these are anything other than real people and real experiences. If nothing else, Dahl deserves some recognition for this chapter and its success in bringing the human reality of nuclear war into a context that might have felt more familiar to readers of the time than the reports gradually coming in from the “far-flung” cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The fact that Dahl never received this recognition is partly down to the shortcomings of the rest of the book. But his subject was also one that the public was never likely to embrace at the time. In his book Nuclear Holocausts: Atomic War in Fiction, Paul Brians notes that “few novels depicting nuclear war either outside or inside of science fiction were published before 1950,” and the few that were published were “not widely reviewed or sold.” This general trend has largely continued to this day: while other events from the Second World War have entered the cultural consciousness, “Hiroshima has had nothing like the literary impact of other great military events.”

This lack of cultural awareness creates a serious problem—especially now, as only a few survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain. One of these is 91-year-old Setsuko Nakamura (now Thurlow). Last year, she wrote a letter to the Economist in which she warned of “the dangers of fading memories and weakening moral revulsion of nuclear war.” She observed: “Too often I read articles discussing nuclear weapons in abstract, analytical terms, as if they were chess pieces.” In her estimation, the “appalling human consequences of nuclear weapons” are still not well enough understood or discussed.

Facts and treaties are important. But these are “abstract, analytical” elements, forcing us into the kind of overview perspective that Dahl seemed to warn of in Some Time Never. Stories are essential for bringing those “appalling human consequences” to life. Stories make them tangible—more than ever in a world in which almost no one living has seen the use of atomic bombs firsthand. And they serve as a call to action more powerful than any statistic.

Despite his embarrassment at its shortcomings, Roald Dahl’s Some Time Never has a critical place in the small body of cultural works that deal with the threat of nuclear war head-on. Seventy-five years after the book’s publication, Dahl would no doubt be relieved to know that the world has not yet succumbed to nuclear folly again. But nor have we progressed. Rather, we have reached the stalemate position of mutually assured destruction—a supposedly balanced position, which has actually brought us close to the brink of annihilation on several occasions. And now, due to the Russia-Ukraine War, we face an increased risk of nuclear escalation so great that the Doomsday Clock, which symbolically represents mankind’s proximity to global destruction, has been set at 90 seconds to midnight—the closest it has been in its 76-year history.

In this context, Roald Dahl’s forgotten debut novel is worthy of reappraisal and reprinting. It can help keep the human reality of nuclear warfare in the public consciousness and inspire a new generation of writers and artists to address this urgent subject in the culture. It may not be his greatest work, but Some Time Never is nonetheless an undervalued novel, with a prophetic vision of doom that can only be averted if we choose not to look away.