History

A Mixture of Pride and Shame

The left’s refusal to frame the British Empire as anything but a force for pure evil makes for effective culture-war politics. But it also makes for bad history.

It was December 2017, and my wife and I were at Heathrow airport, waiting to board a flight to Germany. Just before setting off for the departure gate, I could not resist checking my email one last time. My attention sharpened when I saw a message in my inbox from the University of Oxford’s Public Affairs Directorate. What I found was a notification that my “Ethics and Empire” project, organized under the auspices of Oxford’s McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics & Public Life, had become the target of an online denunciation by a group of students; followed by reassurance from the university that it had risen to defend my right to run such a thing.

So began a weeks-long public row that raged over the project, which had “gathered colleagues from Classics, Oriental Studies, History, Political Thought, and Theology in a series of annual workshops to measure apologias and critiques of empire against historical data from antiquity to modernity across the globe.” Four days after I flew, the eminent imperial historian who had conceived the project with me abruptly resigned. Within a week of the first online denunciation, two further ones appeared, this time manned by professional academics, the first comprising 58 colleagues at Oxford, the second, about 200 academics from around the world. For over a fortnight, my name was in the press every day.

What had I done to deserve all this unexpected attention? Three things. In late 2015 and early 2016, I had offered a partial defence of the late-19th-century imperialist Cecil Rhodes during the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in Oxford. Then, in late November 2017, I published a column in the Times, in which I referred approvingly to Bruce Gilley’s controversial article The Case for Colonialism, and argued that the British (along with Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders) have reason to feel pride as well as shame about their imperial past. Note: pride, as well as shame. And a few days later, third, I finally got around to publishing an online account of the “Ethics and Empire” project, whose first conference had in fact been held the previous July.

Contrary to what the critics seemed to think, the Ethics and Empire project is not designed to defend the British Empire, or even empire in general. Rather, it aims to select and analyse evaluations of empire from ancient China to the modern period, in order to understand and reflect on the ethical terms in which empires have been viewed historically. A classic instance of such an evaluation is St Augustine’s The City of God, the early-fifth-century AD defence of Christianity, which involves a generally critical reading of the Roman Empire. Nonetheless, Ethics and Empire was conceived with awareness that the imperial form of political organisation was common across the world and throughout history until 1945; and so does not assume that empire is always and everywhere wicked; and does assume that the history of empires should inform—positively, as well as negatively—the foreign policy of Western states today.

Thus did I stumble, blindly, into the Imperial History Wars. Had I been a professional historian, I would have known what to expect, but being a mere ethicist, I did not. Still, naivety has its advantages, bringing fresh eyes to see sharply what weary ones have learned to live with.

One surprising thing I have seen is that many of my critics are really not interested in the complicated, morally ambiguous truth about the past. For example, in the autumn of 2015, some students began to agitate to have an obscure statue of Cecil Rhodes removed from its plinth overlooking Oxford’s High Street. The case against Rhodes was that he was South Africa’s equivalent of Hitler, and the supporting evidence was encapsulated in this damning statement: “I prefer land to n---ers … the natives are like children. They are just emerging from barbarism … one should kill as many n---ers as possible.” As it turns out, however, initial research discovered that the Rhodes Must Fall campaigners had lifted this quotation verbatim from a book review by Adekeye Adebajo, a former Rhodes Scholar who is now director of the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg. Further digging revealed that the “quotation” was, in fact, made up from three different elements drawn from three different sources. The first had been lifted from a novel. The other two had been misleadingly torn out of their proper contexts. And part of the third appears to have been made up.

There is no doubt that the real Rhodes was a moral mixture, but he was no Hitler. Far from being racist, he showed consistent sympathy for individual black Africans throughout his life. And in an 1894 speech, he made plain his view: “I do not believe that they are different from ourselves.” Nor did he attempt genocide against the southern African Ndebele people in 1896—as might be suggested by the fact that the Ndebele tended his grave from 1902 for decades. And he had nothing at all to do with General Kitchener’s concentration camps during the Second Boer War of 1899–1902 (which themselves had nothing morally in common with Auschwitz). Moreover, Rhodes did support a franchise in Cape Colony that gave black Africans the vote on the same terms as whites; he helped to finance a black African newspaper; and he established his famous scholarship scheme, which was explicitly colour-blind and whose first black (American) beneficiary was selected within five years of his death.

However, none of these historical details seemed to matter to the student activists baying for Rhodes’s downfall, or to the professional academics who supported them. Since I published my view of Rhodes—complete with evidence and argument—in March 2016, no one has offered any critical response at all. Notwithstanding that, when the Rhodes Must Fall campaign revived four years later in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, the same old false allegations revived with it. Thus, in the Guardian newspaper, an Oxford doctoral student (and former editor of The Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal) was still slandering Rhodes as a “genocidaire” in June 2020.

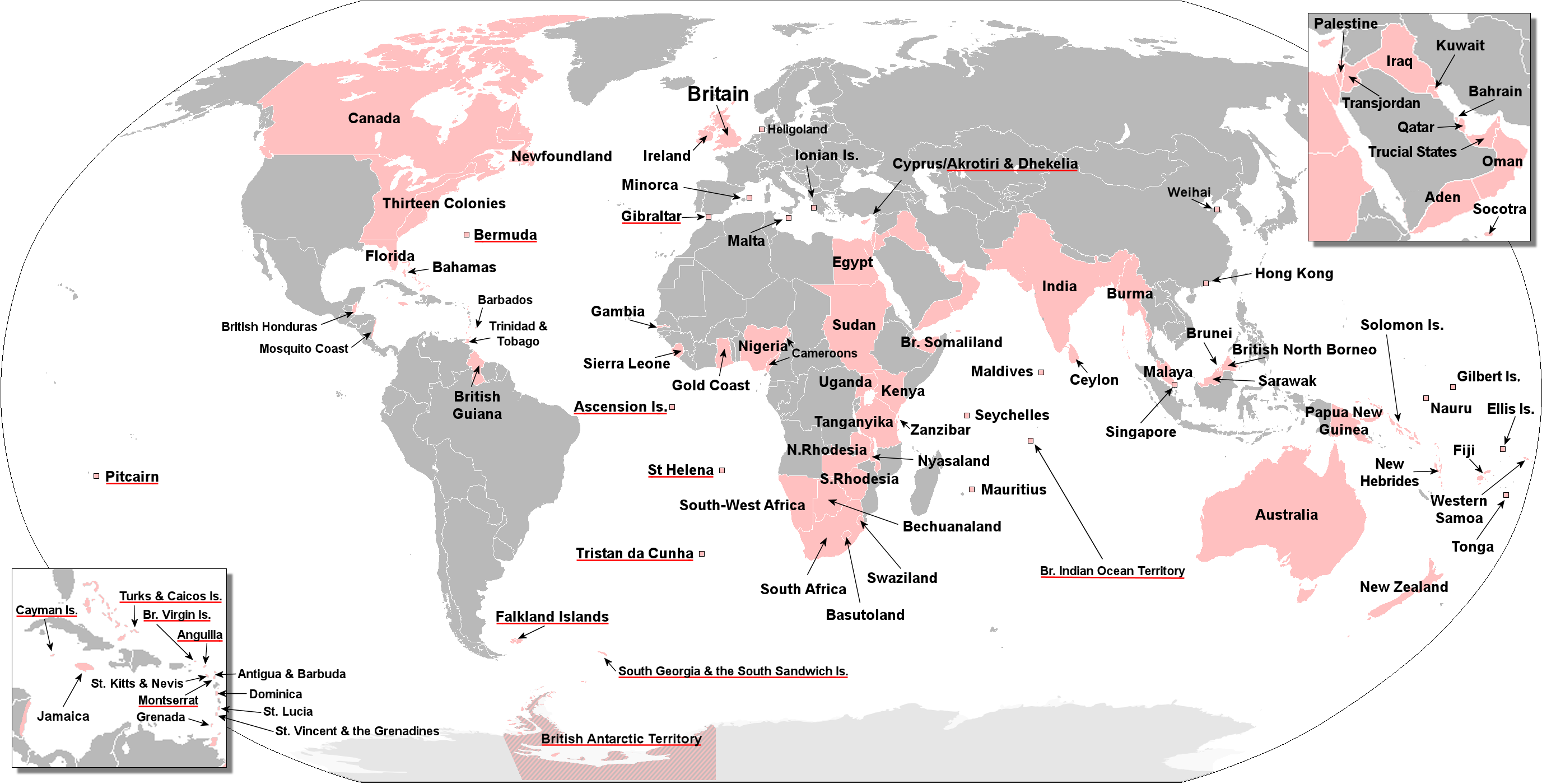

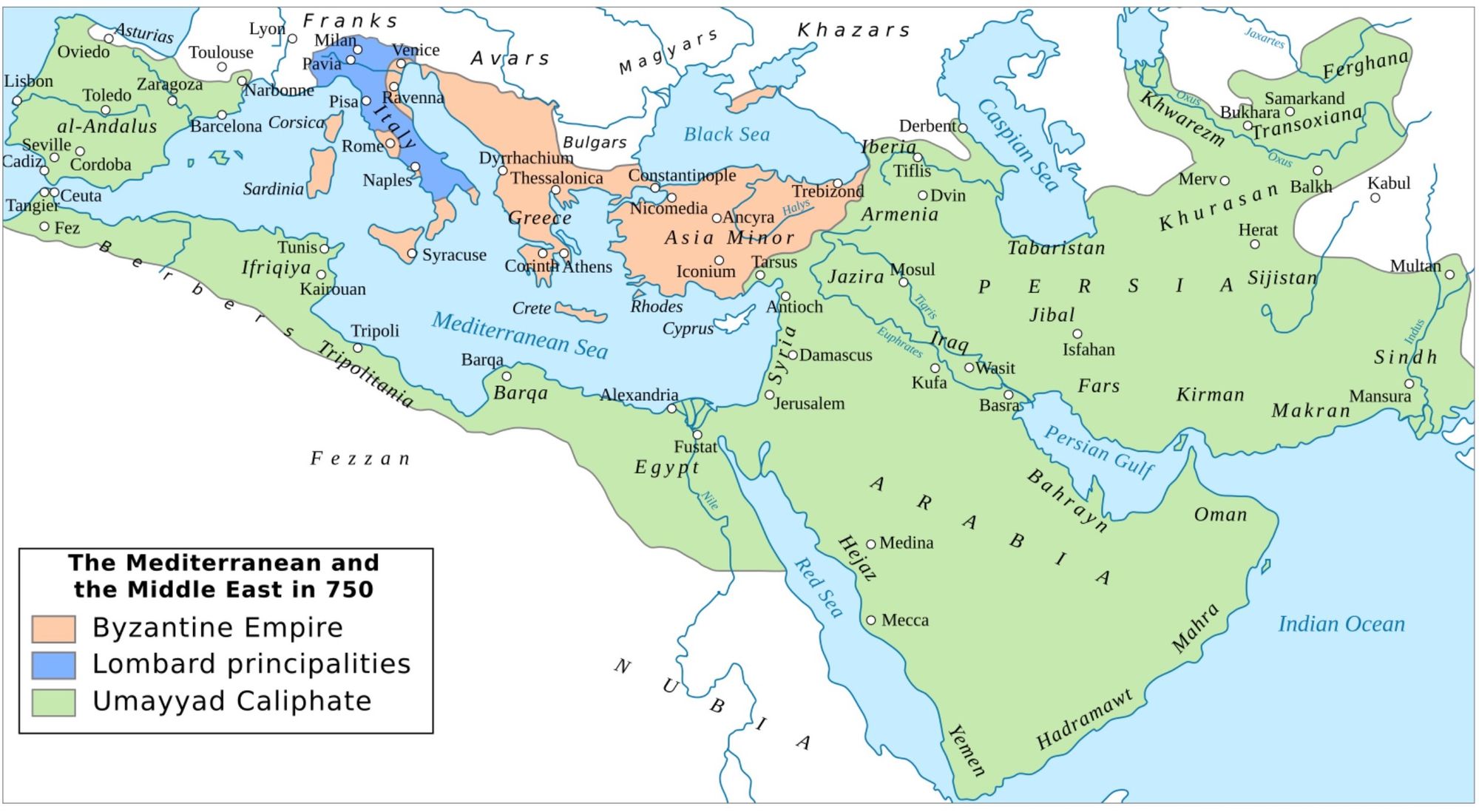

This unscrupulous indifference to historical truth indicates that the controversy over empire is not really a controversy about history at all. It is about the present, not the past. An empire is a single state that contains a variety of peoples, one of which is dominant. As a form of political organisation, it has been around for millennia and has appeared on every continent. The Assyrians were doing empire in the Middle East over 4,000 years ago. They were followed by the Egyptians, the Babylonians, and the Persians. In the sixth century BC, the Carthaginians established a series of colonies around the Mediterranean. Then came the Athenians, followed by the Romans and after them the Byzantine rump.

Empire first appeared in China in the third century BC and, despite periodic collapses, still survives today. From the seventh century AD, Muslim Arabs invaded east as far as Afghanistan and west as far as central France. In the 15th century, empire proved very popular: the Ottomans were doing it in Asia Minor, the Mughals in the Indian subcontinent, the Incas in South America, and the Aztecs in Mesoamerica. Further north, a couple of centuries later, the Comanche extended their imperial sway over much of what is now Texas, while the Asante were expanding their control in West Africa. And in the 1820s, King Shaka led the highly militarised Zulus in scattering other South African peoples to several of the four winds, conducting at least one exterminationist war in the process.

Set in this global historical context, the emergence of European empires from the 15th century onwards is hardly remarkable. The Portuguese were first off the mark, followed by the Spanish, and then, in the 16th century, by the Dutch, the French, and the English. The Scots attempted (in vain) to join their ranks in the 1690s, and Russians did so in the 1700s. What is remarkable, however, is that the contemporary controversy about empire shows no interest at all in any of the non-European empires, past or present. European empires are its sole concern, and of these, above all others, that of the English (or, as they became after the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707, the British).

The reason for this focus is that the real target of today’s anti-imperialists or anti-colonialists is the West—more precisely, the Anglo-American liberal world order that has prevailed since 1945. This order is supposed to be responsible for the economic and political woes of what used to be called the “Developing World” and now answers to the name “Global South.” Allegedly, it continues to express the characteristic white supremacism and racism of the old European empires, displaying arrogant, ignorant disdain for non-Western cultures, thereby humiliating non-white peoples. And it presumes to impose alien values and to justify military interference.

The anti-colonialists are a disparate bunch. They include academic “post-colonialists,” whose bible is Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and who tend to inhabit university departments of literature rather than those of history. For one expression of their view, take Elleke Boehmer, professor of world literature in English at the University of Oxford, whose departmental web page presents her as “a founding figure in the field of colonial and postcolonial studies.” In 2020, she wrote:

Is killing other people bad? Yes. Is rapacious invasion bad? Absolutely. And so it must follow that empires are bad, as they typically operate through killing and invasion. Across history, empires have involved the imposition of force by one power or people upon others. That imposition generally involves violence, including cultural and linguistic violence, such as the suppression and subsequent loss of native languages … Empire requires exclusion to operate … spawning wars and genocides … No empire sets out to bring law and order to other peoples in the first instance. That is not empire’s primary aim. The first motivating forces are profit and more profit.

How historically accurate, politically realistic and morally sophisticated such a view is, readers may judge for themselves in the light of what follows in my newly published book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (from which this text is adapted). But whatever its intellectual merits, academic “post-colonialism” is not just of academic importance. It is politically important, too, insofar as its world view is absorbed by student citizens and moves them to repudiate the dominance of the West.

Thus, academic post-colonialism is an ally—no doubt, inadvertent—of Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia and the Chinese Communist Party, which are determined to expand their own (respectively) authoritarian and totalitarian power at the expense of the West. In effect, if not by intent, they are supported by the West’s own hard Left, whose British branch would have the United Kingdom withdraw from NATO, surrender its nuclear weapons, renounce global policing, and retire to free-ride on the moral high ground alongside neutral Switzerland. Thinking along the same utopian lines, some Scottish separatist-nationalists equate Britain with empire, and empire with evil, and see the secession of Scotland from the Anglo-Scottish Union and the consequent break-up of the United Kingdom as an act of national repentance and redemption. Meanwhile, with their eyes glued to more domestic concerns, self-appointed spokespeople for non-white minorities claim that systemic racism continues to be nourished by a persistent colonial mentality, and so clamour for the “decolonisation” of public statuary and university reading lists.

In order to undermine these oppressive international and national orders, the anti-colonialists have to undermine faith in them. In his novel The Man Without Qualities, which lay unfinished at his death in 1942, Robert Musil mused on the decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before the First World War: “However well founded an order may be, it always rests in part on a voluntary faith in it … once this unaccountable and uninsurable faith is used up, the collapse soon follows; epochs and empires crumble no differently from business concerns when they lose their credit.” One important way of corroding faith in the West is to denigrate its record, a major part of which is the history of European empires. And of all those empires, the primary target is the British one, which was by far the largest and gave birth to the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. This is why the anti-colonialists have focused on slavery, presenting it as the West’s dirty secret, which epitomises its essential, oppressive, racist white supremacism. This, they claim, is who we really are. This is what we must repent of.

Politically, this makes good sense. If you want to make others obey your will, it is surely useful to subvert their self-confidence and exploit their guilt. If Henry Kissinger is to be believed, ever since Sun Tzu’s Art of War in the fifth century BC, China’s Realpolitik has placed a premium on gaining psychological advantage. Certainly, its agents are looking to gain that now. In 2011, a British diplomat in China was told, “What you have to remember is that you come from a weak and declining nation.” And when, in July 2020, Britain criticised the Chinese regime for running roughshod over the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, in which China had agreed to respect Hong Kong’s relative autonomy and liberal rights, Beijing’s ambassador was quick to dismiss the criticism as colonial interference. Similarly, when the hard Left wants to undercut Britain’s role as a major supporter of the post-1945 liberal international order, or when Scottish separatists want to deepen alienation from the United Kingdom, it is politically useful to recount the history of the British Empire as a litany of ugly racial prejudice, rapacious economic exploitation, and violent atrocity.

But this only makes good sense politically provided that the end justifies any means, and you have no scruples about telling the truth. Historically, however, it does not make good sense at all. As with Cecil Rhodes, so with the British Empire in general, the whole truth is morally complicated and ambiguous. Even the history of British involvement in slavery had a virtuous ending, albeit one that the anti-colonialists are determined we should overlook. After the best part of 200 years of transporting slaves to the West Indies and the American colonies, the British abolished both the trade and the institution within the empire in the early 1800s. They then spent a century-and-a-half exercising their imperial power in deploying the Royal Navy to stop slave ships crossing the Atlantic and Indian oceans, and in suppressing the Arab slave trade across Africa.

There is, therefore, a more historically accurate, fairer, more positive story to be told about the British Empire than the anti-colonialists want us to hear. And the importance of that story is not just past but present, not just historical but political. What is at stake is not merely the pedantic truth about yesterday, but the self-perception and self-confidence of the British today, and the way they conduct themselves in the world tomorrow. What is also at stake, therefore, is the very integrity of the United Kingdom and the security of the West.

Adapted, with permission, from Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, by Nigel Biggar. Published by William Collins, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © Nigel Biggar 2023.