Art and Culture

Samantha Geimer and Emmanuelle Seigner in Conversation

The two women most directly affected by the 1977 Polanski scandal discuss guilt, shame, feminism, #MeToo, the media, and the search for truth and understanding.

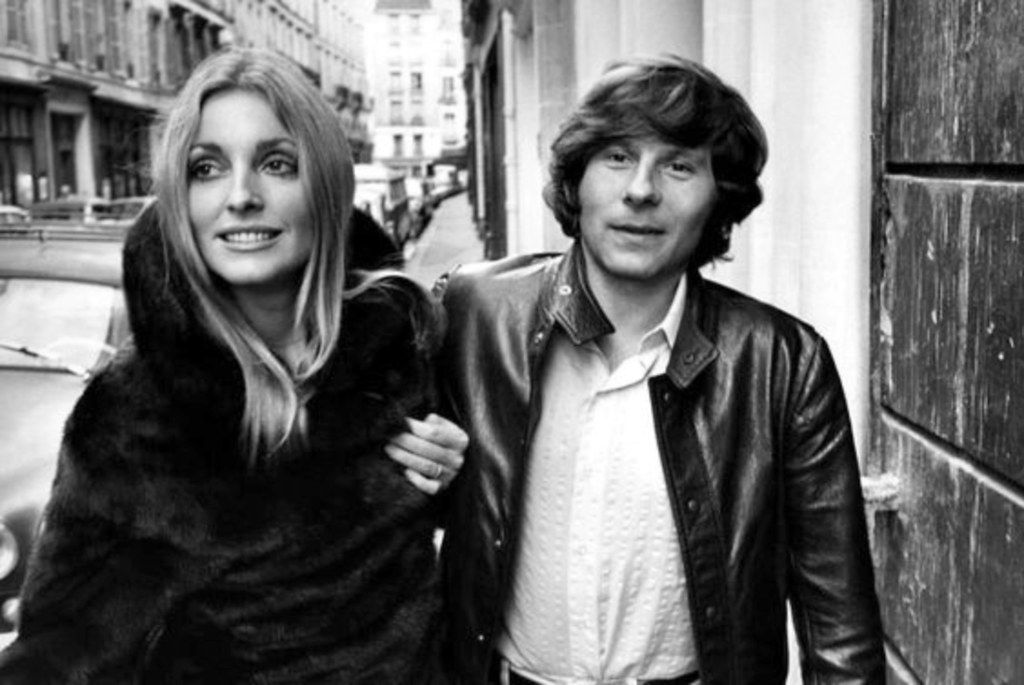

When Roman Polanski was arrested in Zurich in 2009, I was convinced that I had it all figured out. He had raped a 13-year-old girl during a photo shoot in Los Angeles on March 10th, 1977. He had given her champagne and quaaludes and then sodomized her. All of this information can be found in the victim’s Los Angeles County Grand Jury testimony from March 24th, 1977. I had read it and I had counted: the girl, named Samantha Gailey at the time, seemed to have said “no” 17 times, and Roman Polanski seemed to have ignored her throughout. I also knew that a trial had begun because Samantha’s mother had been wise enough to call the police that same night, but that it had never reached its conclusion because Polanski had skipped to Europe before the verdict. As I saw it, the American justice system was only trying to get the Swiss justice system to return a fugitive 32 years after he had fled.

So I was appalled when a bunch of noisy fat cats decided to defend Polanski. It may seem unreal in our post-#MeToo world, but at the time, hundreds of personalities of all stripes spoke out in the media in support of the filmmaker’s immediate release. This was the dominant discourse back then, at least in France: Samantha Gailey had not really been “raped,” the story was not that serious, and Polanski was too great an artist to be a criminal. In a vain attempt to balance the scales, I co-authored an article with Lola Lafon, which was published in Slate and Libération in June 2010. There had been a few waves, but I still thought I knew the basic facts.

Then, a few months later, I came across Wanted and Desired, Marina Zenovich’s 2008 documentary (produced by the BBC) about the Polanski affair. Zenovich takes no side other than that of the truth. The film is hardly a defense of Polanski—the contrast between the description of his “encounter” with Samantha Gailey in his autobiography and the latter’s deposition is particularly overwhelming. But the film also exposes the monstrous media and judicial fiasco in which the defendant and the plaintiff both became entangled.

As is so often the case, the truth turns out to be far more messy than the headlines would have us believe. Zenovich’s work helped me to realize that Samantha Gailey had indeed been raped, but that the law had considered the event null and void, ruling it an “unlawful sexual intercourse.” This was partly to spare the young victim the ordeal of a trial. As Lawrence Silver, the lawyer for Samantha Gailey and her family, remarked when he discussed the decision to drop the most serious charges, including rape, to protect his client: “A stigma would attach to her for a lifetime and justice is not made of such stuff.”

That story found an echo in my own life. A little over a decade earlier, I had been raped and decided not to press charges. Why not? Because I did not want to give anyone, least of all my rapist, the power to destroy me for something that meant so little to me. According to a now-outdated notion, the only power the wicked have over us is the power we give them. This had been my rapid point of entry into orthodox feminism—and I left just as quickly. During a group discussion intended to support victims of sexual violence, I had found myself in the defendant’s dock. I kept repeating that my rape had done nothing to me, that I had not been harmed by it, and that once I understood that the guy had not heard my protests and that resistance would only put me in physical danger, I simply waited for it to end.

For this, I was told that I was “in denial”—that I needed to “let go” and express my anger, my rage, and my pain, all of which I was pathologically “repressing.” During the few sessions I was able to tolerate, my contrarian mind reinforced and cemented my apathy. One of the other women in our circle experienced exactly the opposite. She too told the group about a rape she had brushed off immediately after it happened. But in response to the urging of the group, she had provided the emotional release they expected of her and gradually disintegrated into explosive sobs and shivers. On the face of the group moderator, I saw the triumphant smirk of someone who had managed to create a malleable new victim. It was the smile of a fanatic, deaf and blind to the interests of anyone crushed by her relentless pursuit of what she thought was justice.

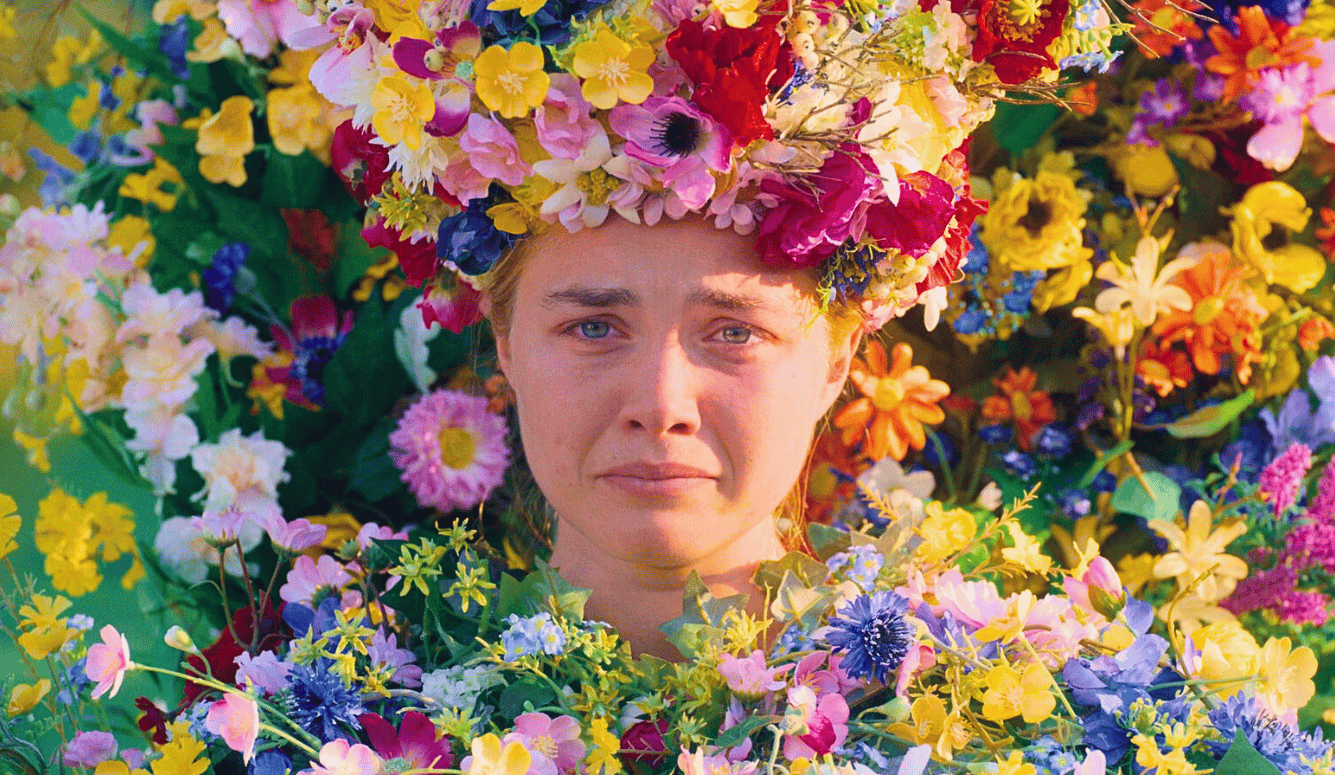

The second echo came when I read The Girl: A Life in the Shadow of Polanski, the memoir that Samantha Gailey—now Geimer, a 60-year-old married mother—wrote in collaboration with her lawyer and the writer Judith Newman. I engrossed myself in this book in 2017. Online, I saw Geimer express the same reservations about the #MeToo movement that I harbored and receive the same accusations of betrayal that I had. In her book, she explains that Polanski’s 2009 arrest in Switzerland had triggered a desire to tell her story. She says that the civil suit filed against the filmmaker for sexual assault in 1988—and won in 1993—was motivated by his account of the rape in his autobiography and by a comment he made to Lawrence Silver in Paris when the lawyer came to question him: “You know, if you had seen her naked, she was so beautiful, you would have wanted to fuck her too.” But she also reveals, without ambiguity, her decision to forgive Polanski—“not for him … I did it for me.” Hatred, she explains, is the poison we swallow in the belief that it will kill someone else. As soon as I closed the book, I wrote to Samantha to tell her of the strange feeling it had evoked in me—of having found in her a combination of soulmate and mother from a parallel universe (her oldest son is a year younger than me). As the closing line of Casablanca has it, this marked the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

And what of Polanski’s wife, Emmanuelle Seigner? Her own account, published last fall in Une Vie Incendiée (L'Observatoire), has created a third echo—that of the collateral damage that virtuous vigilantes inflict and then sweep under the rug. The actress and singer recounts the months following her husband’s arrest in 2009, and her anger at the injustice of seeing her family and career destroyed by opprobrium. This is the impossible life of a woman whose only crime is a refusal to leave her husband. She is yet another noncompliant feminist, and the other woman caught in the shadow of the Polanski scandal. Her account convinced me that this story is much bigger than the man who had, and has, so far, played the title role.

This introduction was originally published in Le Point here. The interview that follows was originally published in Le Point here. The conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Peggy Sastre: Why did you agree to this interview?

Samantha Geimer: I thought it would be exciting for us to get together and…

Emmanuelle Seigner: …and meet!

SG: And meet, of course. But to speak together in solidarity with capable adult women who have opinions and don’t necessarily fall into the trap of everybody blaming and pointing fingers. I thought it would be a good opportunity to do something different.

ES: And for me, I thought it was a great occasion to actually meet Samantha because we’ve been together all our lives, in a sense, even though we had never met. I mean, since I’m in the picture, we are somehow connected to this issue. Also, I thought it was very interesting because there is so much crap out there about this story. Some really stupid things are said over and over again. And nobody knows it better than Samantha, so I thought the time had come to tell—to fight for—the truth. Even if people don’t want to hear it. And they don’t even care!

SG: I agree. You know, every time things erupt in the press, I think about you and your family and I understand. So yes, perhaps it’s weird, but we have a connection. It’s been years and years, and it continues even now. So you feel connected to someone even though you have never met them because they’re having the same experiences.

ES: I think it’s a great thing, and it’s very moving to me to actually meet you. It makes me feel less lonely.

SG: I remember clearly thinking about you. Because I understand. Polanski’s arrest was a life-changing event for all of us.

ES: Yeah, me too. Both of our families lived kind of the same thing at the same moment. It was not good. When Roman got arrested, I also thought a lot about you and your family. I imagined you had the same kind of nightmare.

SG: The difference is that you had your innocence. You have no part in any of this. Just like my family and my kids and [my husband] Dave, even if he got used to it. But it’s not fair that it bleeds onto everyone else, that everyone has to suffer.

ES: It was also a very strange sort of situation because nobody was really talking about what happened to you anymore until they arrested him.

SG: And until it’s useful for somebody and then they talk about it. But only because it’s useful to this or that person. It’s just so frustrating.

ES: Yeah, they use it. Exactly. As a weapon.

SG: And it’s not like they care. Trust me, I’m well aware. I feel like people will be surprised for us to be together in solidarity, you know, making our points. And you know what? I have a little bit of hope that we’ll upset people.

ES: The thing is, when I talk, nobody listens to me. When Samantha talks, nobody listens to her. So, maybe together, as a team, it will work better.

SG: Even if they don’t listen, they’ll notice! So we have that going for us.

PS: Since the #MeToo movement, we hear that “women’s voices are being liberated,” and that women are finally being heard. But you are both women and you are not being listened to.

SG: No, never. I just keep trying, but people don’t want to hear the truth when it doesn’t suit their purpose. It always has to be someone using it for themselves somehow, whether it’s journalists or pundits or TV people or the district attorney or … It’s always about the person who wants something for themselves trying to take what should have been my tiny little story and turn it into something that they can use. And to me, that is opposite of the whole purpose of caring about me or caring about women. You can’t say you tell my story because you care about me or you care about women when, really, you’re just saying things that aren’t true. Doing that, you don’t care about me at all. It’s a cover, it’s fake, it’s hypocritical.

ES: When my book came out, I gave a TV interview and the journalist kept bugging me and bugging me … and I was just about to show him my boobs and say “You see I am a woman, right? Why don’t you listen to me? Why don’t I have the right to be listened to, too?”

SG: Because it’s fake. It’s a fake care, a fake liberation. People say women’s voices are liberated, but what they really want is for women to be damaged and in pain. They want to exploit that and they’re not satisfied if there’s not some shock value or something…

ES: Dirt. They want dirt.

SG: Yeah. And that’s not liberating. That doesn’t help women. I think there’s a lot of good in the #MeToo movement, but when it’s about dragging people’s trauma out for the benefit of everybody else and enjoying it … That’s not good, you’ll never get better like that. Doing that, what you are really doing is telling women they can never recover, they can never get better. They can never move on, never heal. You’ll be this sad little damaged thing for all eternity. That’s what they want, they want damaged women. But it does not help women to seek out their damage and celebrate it. That’s not helpful. That only hurts women. I think it has turned into something really backward.

ES: Right, but I also feel like there’s a problem with society. I mean, they want to see you as a victim and they want to see me as a wife. Nothing else, that’s it. That’s terribly sexist to me.

SG: Indeed. That’s sexism. Everything. With the way I get treated, with the way you get treated. They would never treat my husband or my sons like that.

ES: If I was the one having problems with the justice system, my husband would never be treated like I am.

SG: It’s because we are women that we are treated like this. It’s the same with me, with you, with your daughter. It’s okay to treat a woman that way and not listen a little bit to what we have and want to say.

ES: They want a woman to be a victim and that’s it. It’s a form of control, of domination.

SG: I was just thinking that they would never treat Dave like you. Reporters came tramping to my house and confronted my sons, but in a very gentle way. Their words were very cautious. And the words people use to Dave are very cautious and I’m like … that’s because he’s a man! So, yes it’s sexism. That’s why we’re here, we won’t accept it anymore.

ES: You know, after #MeToo, although I was doing a lot for fashion, I couldn’t get a contract for movies and so on. I’m suddenly radioactive, especially in France. But what did I do?

SG: You didn’t do anything, of course, and this all happened long before you met Roman, so you’re completely innocent. But I don’t know, it’s been a difficult time since #MeToo.

ES: And with all that “cancel culture.” It’s like they want perfect people. As recently as this year’s Césars in France, there has been this exclusion of actors caught up in legal proceedings, against whom there are complaints or suspicions. As if an artist has to be perfect in every way and perfectly moral, without flaws or baggage. People who don’t drink, that don’t take drugs, who didn’t have a car accident.

SG: People who don’t have a past, who didn’t live through the ’70s and ’80s. That kind of life is very hard to explain to people. You just can’t even try. When you say it out loud, people have all kinds of weird reactions.

ES: That’s where we are also alike. We are from the same generation.

SG: Yes, we came of age in the same world, in the same era, when things were very different. Feminism was very different. It was about being strong, about being equal. And equal means having opportunities but taking your knocks like everybody else. It’s not about privilege and protection. It was a feminism of “get up there, do that job and if somebody is unkind to you, well suck it up! You wanted to be part of the world? So, big news, the world’s shitty and you can’t cry your way out of it!” They’ve managed to take away women’s sexual freedom without having to do anything. Just by convincing younger women that sex is violence, bad, dangerous, that men take it from you and damage you somehow. All this happened spontaneously. Women took their sexual freedom away from themselves! In a way, it’s like what conservatives used to do: they use fear to diminish women. Next thing you know, you won’t be able to go to work because, hey, there’s men out there and it’s not safe. They might talk to you or they might be rude to you, so maybe you should just stay at home and have babies, okay? It’s like women are walking themselves back into the cage.

ES: I think it has a lot to do with AIDS, don’t you think? All the sexual freedom that was taken from us. And now, COVID. I was reading Plagues and Peoples by William H. McNeill, which explains how mores and the fabric of society have a lot to do with epidemics. Because in the ’70s, there was the pill, penicillin, no AIDS, no danger…

SG: I guess we had all the fun we could have, and then we got married and we didn’t have to worry anymore. You know we got married the same year?

ES: You and me? 1989?

SG: Yep. We’re tied that way too. We married the same year and had two children after that. And you are the same age as my husband. Anyway, we can’t go back and AIDS is real. The ’70s or ’80s are over. Sorry people! We had all the fun and spoiled it for everybody else.

ES: I feel I didn’t have enough of the fun.

SG: I had too much fun. Besides, I think a lot of it is just about morality and control. A lot of it is just about sexism and putting women back in their place. Because a woman’s sexuality is a powerful thing and they’re afraid of it, and they don’t like it. So they want to shame you. Because they’re afraid of women having any type of power at all. And sexuality is a powerful thing.

ES: I remember when I started working. I was a model when I was 14 and I met a photographer in the Luxembourg Garden in Paris. I was doing well, making a lot of money. At the time, all the girls, the models, were sleeping with the photographers and I was no exception. But sex was like a normal thing; a natural part of life. There wasn’t all this doom and gloom about sex.

SG: Sex was recreational and sometimes transactional. But it was just something you could do if you felt like it. Like any other activity. For fun, for whatever reasons. There was nothing sacred or bad about it.

ES: Today, it is as if female desire is denied, wiped out.

SG: That’s true.

ES: And that’s sad.

SG: Sad for women and especially for young women. I can’t imagine being a young woman coming of age nowadays. It’s dreadful.

ES: It’s like we can’t have pleasure. We can’t have anything. We are just victims and that’s it. I don’t understand this new feminism, because it’s against everything we fought for, right?

SG: Feminism today is not the one I grew up with. I don’t see what’s feminist in screaming and yelling about how you’re victimized. Your feminism is saying women are weak, that I’m weak. Today, there’s a value in your pain and there’s an industry built on the pain of women. An industry that exploits people who have pain for whatever reason. People don’t know what they’re getting into. Me, I know because I’ve been doing this for a long time. They come at you with all kinds of good intentions: “We want you to talk because people want to know, want to learn what this is really all about.” But the truth is, all they want is for their careers and their shows. They don’t want you because it will be good for you or for women, but because they are booking people for the show and need you because that’s good for them. Plenty of shows are like “Well, you’ve been hurt so much, right? Well, get over here, I’d like to hurt you some more.”

ES: I feel that too, it’s like a lot of people want to use this story.

SG: And to use you as a weapon. But that’s not who I am. When I see women coming into the media with whatever story they might want to tell, what they think is true, I always want to contact them and ask: Have you thought this through? You might feel like this is going to benefit you, but you’re probably just being used by somebody who wants your story, your trauma, and your pain because that’s valuable to them. They don’t want to help you. Like the attorney Gloria Allred, she just drags women out and exploits their pain and calls herself a victims’ advocate. I’m sorry, but that’s not advocacy.

PS: Were you approached by Gloria Allred?

SG: In 1977. I don’t know precisely because it was shaky back then, but my mom thinks she was around, yes. There was a lot of hovering around until we said we didn’t want any money, then poof!, everybody was gone. That’s what bothers me the most. You don’t call yourself a victims’ advocate when you’re the opposite of that. In 2017, there was this woman, Robin M., whoever she is, who came out and said that something happened to her with Polanski when she was a young girl, but she provided no further details. And that’s also a problem: if something bad happened to you, say what, precisely, happened. Anyway, at the time, Gloria Allred called me and wanted me to speak with Robin. I’ve answered that I would be glad to speak with her, but confidentially. It would be a talk between me and her, because I would advise her to be very careful and to think about what Gloria Allred really wanted. I would answer her questions and give her my honest advice. But you know what? Once I said it had to be confidential … nope, she was gone. So that’s how much she cared about Robin and all her “victims.” So I’m also here to say all these people suck, and they should stop it.

ES: I’ve read your book recently where you tell your story from your side, and you explain that you had the idea of this book when Roman was arrested in 2009. And so did I, I did the same exact thing without knowing you did it before. It’s funny and very moving to me to see that, on the other side of the ocean, of the planet, we were sort of living the same kind of thing. You with your family, me with my family and it’s crazy.

SG: It’s horrid, I’m just sick about all that.

ES: And it’s really bad because my kids, who were 11 and 16 at the time, had their dad taken away from them, during nine weeks, and they didn’t understand why.

SG: What you lived through is worse than anything that happened to my family, Dave and the boys. At the time, I would sit and think about it. That made me sad, made me upset. I was powerless to do anything about that. It was shocking and horrible. I thought a lot about you and your family. When I saw the photographers outside your chalet…

ES: And for what? In the name of what?

SG: To exploit people’s pain and trauma for their own benefit. None of this was because anybody cares about me or what happened to me. They act as if they’re doing some kind of justice or supporting me in some way, when it’s the opposite of what I want and everything I say I want. But somehow, they feel like they have the moral high ground and they really don’t. It certainly isn’t the moral high ground, it’s the low road. I mean, the extradition attempt, the fact that Roman got arrested like that was so unfair, and so wrong, and so unjust. As the truth finally squeaks a little bit, everyone should know now that Roman served his sentence. Which was long if you ask me. Nobody wanted that, but that’s what happened and it was more than enough. It was sufficient. He’s paid his debt to society. That’s what happened. End of story. He did everything he was asked until it just became too crazy and he couldn’t do it anymore. So anyone who says otherwise, who thinks, “Oh yes, he belongs in jail” is wrong. He doesn’t and he didn’t.

ES: You know what I think? I think that because the murder of Sharon Tate was committed by Americans on American soil, in a way, Americans wanted Roman to be a monster, to wipe away the murder. He was a stranger in America—a Polish and Jewish guy—and that allowed them to treat him unfairly. It was 1969, I was three years old and you were six, but I read a lot later when I was writing my book, and I found the way he was treated after Sharon was murdered was horrible. They said it was his fault, because of his weird films, that he was some kind of devil worshiper. That’s plain antisemitism. And Roman was broken. He had just lost his love, his wife, his baby, in such a horrible way.

PS: In your book, Emmanuelle, you write a lot about the murder of Sharon Tate and its effect on you.

ES: Yes, it was a big issue for me. I was afraid of this murder. It was so scary. I went to LA after we made Frantic. I was like 19 or 20 years old, and I went for a publicity tour. One night, at the hotel, I turned on the TV and there was a documentary on Charles Manson. The journalist asked him: “What are you going to do if you get out of jail?” And Manson replied: “I’m going to take care of this Polish guy who lives in Paris.” I was terrified.

SG: And that’s now part of your life as well. You have to incorporate it in your life. As our loved ones had to. Poor Dave, he didn’t realize what he was getting into. I didn’t tell him about it right away. In my family, we never talk about the incident. My sons didn’t know about it for a long time either, until it came back in my life and into theirs. In 1988, a friend of mine in England saw an article about it, in the Sun if I remember correctly, and she mailed it to me. And when the letter arrived, that’s when I thought, “Oh God, I have to tell Dave.” At the time, it was like bombs were dropped on our life. I knew after 10 years, it had found me. Things like that are pretty rough on the people who shouldn’t have to bear the burden.

ES: And on you too.

SG: Of course. And I used to be frightened and fearful. But then I decided to come out and to tell my story. Perhaps no one will ever listen to it, but I’m just going to keep telling it. And now I’m not afraid anymore. They can come and find me.

PS: Was writing your book somewhat stressful though?

SG: It was a stressful time and there was certainly a little bit of stress, even for my writer who I loved. There’s always some pressure to make it a little worse than it was. I didn’t want to do that.

PS: For example?

SG: Well, this might not sound important, but it was important to me. When I described Polanski, I compared him with a ferret, but in a bad way. It wasn’t like that in my mind. I had a lot of animals like pet rats when I was a teenager and I loved them. I think they’re cute and adorable. I don’t want to give the impression I’m someone who’s cataloging the appearance of people like that. It’s not who I am. Also, all the way through the book, they refer to me as a “child” and that kept bothering me. I would have preferred to be referred to as a “teenager.” I was not a child. Yes, I was under 18, but that doesn’t mean I was a “child.”

ES: You’re not really in the same age category when you pass 13. You’re 10, 11, 12, and then you’re 13, 14, 15 … Something happened in between!

SG: You know, women are still children at 17 nowadays.

ES: Don’t you think the relationship to age changed as well, from the time we were teenagers? I mean, we both have kids and it’s like they are children until they’re 30.

SG: At the time, we were adults in training.

ES: I was a model at 14 and nobody cared.

SG: Of course. With my mom, we did some TV commercials and people just dropped all the kids off for the day. There were no parents around.

ES: But then, a woman at 40 was considered old. Perhaps that was not better (laughs).

SG: That’s for sure. But I was not a child at 13—not in my own mind. When my sons were teenagers, I never treated them like children. When you get to be a teenager, it’s time to start making decisions, and living, having some freedom. And you know what also bothers me? When I hear a woman say something like, “Oh, I was with this photographer when I was 17 and he hit on me in a rude way, that means he’s a pedophile!” No way. Pedophilia is a real thing, ugly and hurtful. You diminish the seriousness of that crime when you say everybody is a pedophile, especially some guy who just looked at a 17 year old with lustful eyes.

PS: Is celebrity a double-edged sword?

SG: Oh yeah. And I learned about this the hard way, too. Because, when I was younger, I wanted to be famous. I wanted to be an actress, or a singer, or a movie star, whatever. And I wanted the fame more than the skills, the work, the job. Being famous is what I wanted. But then I learned the price of fame. And it’s not pretty.

ES: There is even something suicidal about fame.

SG: I mean, I’m sure there are many benefits and people enjoy it, but it’s a very dangerous thing. I was very happy to take a different path with my life. To not be under that constant scrutiny and expose myself to the harm that can come with fame. Plus, I was too much of a wild child. I’m sure that if I had continued in the movie or the modeling business, I would have been like Drew Barrymore but without the happy ending. I would not have emerged from childhood stardom and remained a strong and talented woman. I would have been one of the cautionary tales of a ruined life. I found trouble so easily, I can only imagine how much more there was out there for me to find!

PS: That’s something I loved in your book—when you write something like, “If you’re a teenager reading this, please find your mom some flowers and apologize right away for all the trouble you will put her through.”

SG: Oh yeah, my poor mom. She was shocked when my book came out. But what could I say? It’s not like I was going to tell her at the time…

ES: There was definitely more freedom at the time.

SG: And safer drugs! I was in a group of friends and everybody was doing the same stuff I did. Going out with people you barely knew for a crazy party, that sort of thing. So when I hear, “Oh, you were acting out because you were traumatized.” Well, maybe, but everybody around me was acting out like me, so, maybe everybody was traumatized. We were doing all the same things together, I was not standing out.

PS: In both your books, there is the nagging question of shame. The shame one feels when facing the gaze of others when in fact one has done nothing wrong.

ES: The thing is, when I met Roman, what happened with you, Samantha, was not such a big shocking thing. It’s not that I didn’t care, but everybody was talking about an “unlawful sexual relationship with a minor” and, as I said before, everybody was doing it at the time…

SG: True. There were teen girls who would have loved to go to Jack Nicholson’s house and have sex with anybody in there that they could get their hands on.

ES: Exactly. For a while, regarding shame, my life was pretty good. We had kids and life was sort of beautiful. Until Roman got arrested in 2009. That was when the words changed. From this point on, everybody was talking—screaming, even—about “rape, rape, rape.” But I never thought that word was appropriate for Roman, because I know him so well. So after that, I felt it was horrible, I felt ashamed and I wouldn’t like people to think that I live with that type of guy, you know?

SG: Well, yeah, but the point is to make you feel shame. They want you to feel shame. And again, Dave does not get that burden and neither do my sons.

ES: But for my kids, it’s really hard.

SG: I can surely understand the suffering. But nobody thinks about that before they open their big mouths. We both have families. We both have friends who get upset when they see the news. Because it’s untrue but also because it’s vulgar and inappropriate. It’s like soft-porn but with a clear conscience. No one has any manners. No one has any thoughtfulness. They don’t care. It seems to me that I would think before saying terrible things about someone or accuse them, especially of things that aren’t true. I would think that this person has a wife, a husband, and children. You must realize that this is going to cause them harm and pain, but no, you’re just going to do it anyway, and then you’re going to act like you have some good cause. I hate the way everyone talks about it. And they only do it because that makes it more interesting for them. We all know what happened, I understand exactly what they’re saying when I hear, “Oh, someone, a man, had sex with a minor and that’s the end of the world.” You know what? If I had been 16, nobody would have batted a frickin’ eye, okay? But at the very beginning of it, it was all my fault, or my mother’s fault. I had to live through all those lies and accusations, and people being very mean. We had this judge who said, in front of my mother and me, in front of other people: “What do we have there? Another mother-daughter hooker team?” That was the environment.

ES: My God, that’s horrible.

SG: Yeah, and it was really like we were bad people. And nobody was shocked, it was not super abnormal for the average person. So yes, perhaps people are shocked now, but big news, you can’t go back and change the way things were and apply your moral outrage to something that happened during a different period of time. So let me be clear: it was never a big deal to me. I didn’t even know that it was illegal, that anybody could get in trouble for that. I was always fine. I’m still fine. And this creation of this thing that happened and isn’t really what happened is a burden. To have to constantly tell people that it was no big deal.

ES: And to tell them the very big deal was the consequences, what happened afterwards…

SG: Yes, starting the very next day. But people don’t want to hear that. People want to hear, “Oh, poor me, I was a damaged little sad thing.” This is what I hate the most. All that stuff that people want to put on me. All your opinions and your outrage and you want to turn what happened into this completely untrue story. And then you’re mad and you want to just put that on my shoulders. It’s gross. I hate that. Can’t I just be fine? Can’t we all just be fine? Just know something happened, it was a long time ago, we were all and remain complicated people with complicated lives and you never know what’s going on for real with other people. And that’s absolutely normal. But no, you can’t, we can’t be fine. You have to be whatever people think I should be, and then they do the same to you. They all want to think you’re living with this horrible person, which we all know isn’t true.

PS: For many people, your story, both of you, is an excuse to hate.

SG: Yes, and this is not who I am. I’m the opposite of that. Again, it feels like a burden, like people want me to carry this hatred for them. But I am not doing that for anybody. And then as soon as they realize I won’t get into this, I’m a terrible person, I’m a rape apologist, I’m bad for other women, I’m spitting in the face of all rape victims. You know what? Fuck you!

ES: And they say the same thing about me.

SG: When they can’t use you, they come after you. And I really think this is geared towards women, a lot of this. Even the age of consent. It’s to control girls, to prevent girls from having sex and from entering the world with all the risks and responsibilities that entails. You know, how about people just have some manners and respect and dignity and class? And just shut the hell up. When there were protests in France and they spray-painted my name all over the walls. What is wrong with these women? Like in what world is that not super-abusive to me and my family? You think you’re helping me or helping anybody? No, that is cruel, abusive, you’re abusing me and my family. And then you act as if you’ve got some great cause, like you’re doing a good thing. But that’s just ugliness. What the hell makes people act like that? You want to put my name on a sign and scream? Okay, but come and talk to me about how I feel about that before, or after, and I’ll tell you. But that goes back to the whole point: they don’t care. They don’t care about me, they don’t really care about Roman, and they don’t care about anybody. They’re not trying to do any good. They’re just angry. How’s that helping women?

ES: I think they’re damaging women acting like that.

SG: Yes, I think that’s bad for women too. Do stupid displays of your moral superiority when you’re not really helping anybody. That is not good for anyone. They just take an action that serves no purpose, except to constantly feed this hatred which is really like a hobby for too many people.

ES: Except the purpose of serving one’s interest at the expense of others.

SG: I mean, what is the point of excluding Roman from the Academy when they keep nominating close to zero women as directors, year after year? I’m sorry, but that’s just a bunch of crap. These guys aren’t doing anything to help women. They’re not supporting women or bringing women into the industry. They do nothing except a PR stunt.

ES: And when they asked me to join the Academy after excluding Roman. How weird was that? They got rid of Roman and three months later they asked me to join. What choice did I have? How was I supposed to look at myself in the mirror if I’d accepted?

SG: I was outraged. Seriously, the nerve they had … I would have been so angry if I were you!

ES: It was shocking, but also very rude.

SG: And it shows how tone-deaf those people can be. How is that supporting anybody? Supporting women? No, they just insulted you! And it was also something like a bribe. They excluded your husband for no real, artistic reason, and they came with this impossible offer after. As a reparation?

ES: And they put me in a bad position. I was about to be the one who turned down the Oscars, which was not good for me or for my career. But of course I said no to them, for the sake of my integrity.

SG: Which makes you a good person. And I also disagree with people who want to stop Roman making movies, or let other people see his movies. People who think we shouldn’t see them, or that we should feel guilty because they’ve heard he did a bad thing and perhaps another one more than 40 fucking years ago. But when Roman, or any other director, makes a movie, that means a lot of people put a lot of work and effort into that. And art is a gift to everybody. We need all the artists and creative people and all the beauty in the world we can get.

ES: And even that changed very quickly. In 2014, Venus in Fur was nominated in seven categories at the Césars, and Roman won the prize for best director. Everyone was happy and cheerful at the time. But now Roman is a pariah. What’s the difference? Some women have come out to accuse him of terrible things. But how do they know they’re not lying?

SG: I will tell you something. If anybody had anything to say about Roman, that he somehow treated them badly, 1977 would have been a really good year to do that. I mean, to help me out. Because I was fighting for my freaking life with my family, with my mother, we couldn’t leave the house! Everybody was attacking us and absolutely nobody came to stand by my side and say: “Hey, you know what? I think she’s telling the truth because something similar happened to me as well.” And it’s not like it was a confidential business—everybody knew what was going on at the time, it was world news! But I didn’t hear of one person—not one—who now says they have a bad story about Roman that they need to tell after all these years. Not one of them was willing to take the risk to help me at the time. But now, decades after the alleged facts? They think it might be beneficial to them and, suddenly, they need to spill it out? Give me a break.

PS: Haven’t you ever had enough? Did you ever think, “Okay, I give up, people will never understand anyway”?

ES: No, never, I’ll never give up.

SG: I don’t feel hopeful. I have been trying to make people listen for a long time. It seems like it’s only getting worse. I’m going to keep trying to tell the truth and make a difference and be honest and try to help your family and Roman as much as I can, and my family as well by making it better, but it might not happen and if it doesn’t happen, that’s okay. I’m at peace with this being a part of my life forever.

ES: We have to make a change. We are two now. We are stronger.