Education

The Fight Over What Children Learn

The model of life they imagine is based on the myth of an all-purpose education designed by experts to allow every child to choose any future they like.

The COVID pandemic has radically changed the ordinary functioning of life across the globe. One of the largest changes has been to education. In the US, schools were closed or moved to Zoom, and those that returned to in-person learning often did so with masks, distancing, and plexiglass shields. There have been many consequences of this change, but one of the most significant is that it brought the day-to-day practices of schools out into the open.

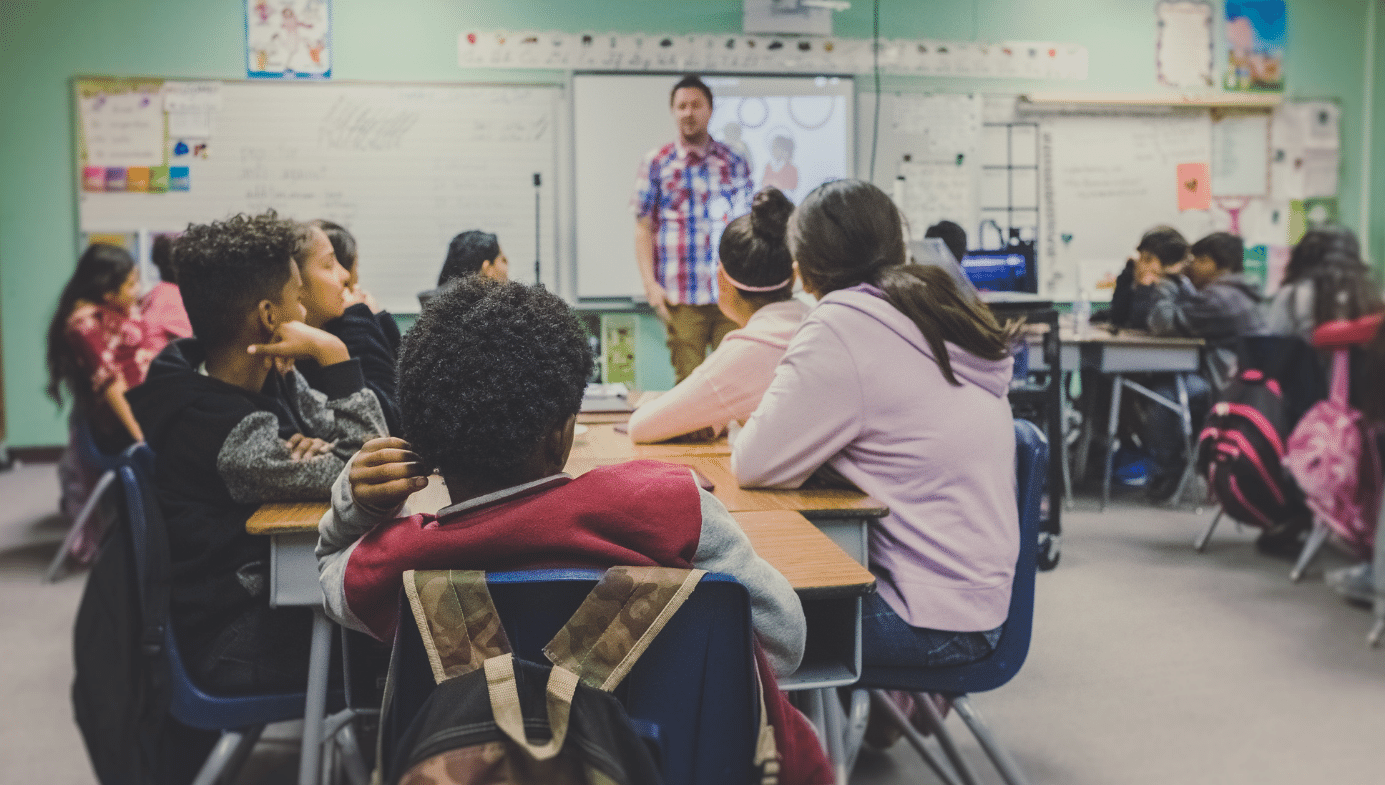

For the first time, Zoom gave parents a window into public school classrooms and many of them didn’t like what they saw. From poor lessons to inappropriate reading material to troubling racial essentialism, parents were roused from their usual passivity to push back against the educational monoculture that dominates school boards, unions, and academic schools of education. This pushback has taken various forms, from ill-advised and authoritarian anti-CRT laws to reasonable transparency laws, and from Twitter campaigns to parent protests at school boards. Parents want schools open, and they want to know what their kids are being taught.

A key moment in this parental awakening came in early October when Democrat Terry McAuliffe insisted that he didn’t “think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.” This was widely seen as a major turning point during the 2021 race for governor in the very blue state of Virginia. McAuliffe had been leading in the polls, but K–12 parents, in particular, abandoned him en masse, and he ultimately lost to Republican newcomer Glenn Youngkin.

This electoral upset exposed—at a national level—the massive gap that had grown between parents on the one hand and pundits, politicians, and teachers’ unions on the other. Parents do want a say in what their children are taught. But not everyone agrees. In December, a New York Times writer stated on Meet the Press, “I don't really understand this idea that parents should decide what's being taught. I'm not a professional educator. I don't have a degree in social studies.”

Well, I am a professional educator. I am a professor of education who teaches teachers, and I can say unequivocally that the belief that one needs to be a professional educator to have meaningful insights as to what ought to be taught reflects a fundamental philosophical and cultural misunderstanding of what education actually is.

People who work in the media or in politics tend to assume that their experiences are unquestionably normative. They are almost exclusively college-educated city-dwellers who were good at navigating a system of schooling that is as much networking and conformity as it is algebra and biology. For them, education is and was a predominantly social and cultural reality, the substance of which happens to be made up of academic content. Successfully achieving careers in high-prestige fields, they excelled at what education researchers have termed the “hidden curriculum”—the underlying norms and values that form the backbone of socialization into particular worldviews and practices. And because they (perhaps subconsciously) equate the business of education with this socialization, they tend to see the social values of education as the legitimate enterprise of education professionals, not parents.

But there’s something deeply mistaken about this view. “Education”—a noun standing on its own—doesn’t exist. There is no set of concepts, ideas, facts, or skills that are intrinsically necessary for individual human beings to possess. The breakdown of school subjects into math, science, English language arts, and social studies is an accident of history. A few different twists and turns and the very categories wouldn’t even exist—math might have been part of science, English may have been part of history, and Latin might still be considered a critical subject. The particular content of these categories might have been different as well. For example, the Singaporean approach to math is very different from the American approach. In Singapore, whole-part relations are used to understand both adding and subtracting, instead of treating the two as discrete domains; students there are learning “math” but it’s not exactly the same math as most American students are learning.

The problem with the idea of “education” runs deeper, however. When we talk about education we’re really talking about “education for…” Education researchers can think deeply and run trials about the best techniques for teaching particular math concepts, and they can study which math concepts are most important to know for someone who wants to be an engineer. But nobody can study whether or not it’s good to be an engineer. We still would have to ask: good for what? For making money? For building bridges? For impressing friends and family?

In fact, the pundits are right—education is about values, but no educator or education researcher can tell us which values are worthwhile. Indeed, the most significant instance in which educators did impose their values with the force of law resulted in one of the most horrific cultural genocides in US history, as Native Americans were forcibly stripped of their language and culture in “Indian schools” designed to Westernize them.

Of course, there are some things that we need from our education system in order to function as a society. We need an education system that will encourage students to grow into law-abiding citizens; we need a system that allows people to flourish and to live happy lives; and we need education that will encourage people to engage in honest work and support their families productively. But which work is important, rewarding, or fulfilling is impossible for education research to determine. The claim that education should promote these public goods is not an educational argument itself. It’s a statement of values, driven by the specific nature of the United States as an open, liberal, generally capitalist, democratic society.

Perhaps the greatest strength of American culture is that we respect and value differences. As a nation of immigrants, we have managed to absorb people from around the world who bring with them all sorts of ideas about what constitutes a good life. Each of these groups has contributed to the American experience by providing a novel model of life for the rest of us to learn from. Similarly, newcomers have incorporated the values of the rest of American society into their own lives.

The choices that local communities make about how they want to live their lives and what they consider valuable are not the sorts of things that can be determined by research. Their ideals do, however, dictate the sort of education that ought to be provided to students to support those values. Thus, by its very nature, to be successful, education in the United States must be organized bottom-up—we can’t organize education until we know the model of life we are educating for, and Americans of all stripes are going to have very different ideas about what that life ought to look like. There’s a reason why America has never had a completely centralized educational system as do the Europeans.

Pundits and politicians who don’t think parents should have a say in what children are taught are actually attempting to prescribe, in a homogenized, top-down way, a model of life that worked for them, as they skillfully and successfully navigated the hidden curriculum of their own environments. But this success, and in particular the explicit curriculum that accompanied it, is not intrinsically better or more valuable than any other, and indeed, we know that it has failed countless students across the country. Their appeal to the authority of education researchers is simply a mechanism to entrench a system that validates their life choices and values, but those with other values, interests, and intellectual inclinations will be ill-served by the very same system.

This is not specifically an anti-CRT argument. CRT happens to represent the present values of a small segment of mostly upper-class urban elites, but any set of values, when uniformly imposed top-down, will harm children and communities who see the world very differently. The trick these policymakers play is to pretend that their conception of education is not just one choice among many, but is the default baseline, from which anything else is a deviation.

The model of life they imagine is based on the myth of an all-purpose education designed by experts to allow every child to choose any future they like. But this has produced an educational system that has left many students with no future; it’s been a failure for all but a select few, precisely because it doesn’t prepare students for all possibilities (an impossibility), but actually reflects the concerns and interests of a small minority of education experts. The idea that those experts, and only those experts, can opine on what to teach and how to teach it is self-serving. Parents sense this and respond accordingly.

It’s not clear whether this new parental awareness will translate into any sort of meaningful reform of the public school system. The system hasn’t changed all that much, and public education is still roiled by the disruptions of COVID. We will have to see what education looks like on the other side of this pandemic before we can assess whether or not parents’ efforts have yielded fruit. But, regardless of the degree of systemic change, one thing is clear: parents are now paying attention, and quite reasonably, they have strong views on what they want their children to learn.

As one of the “professional educators” who supposedly has legitimate insight into the appropriate workings of education, I couldn’t be happier to see parents take the reins. Education is an expression of culture and values, not just a series of facts, and values belong to parents and their communities. As a researcher I can answer education questions on all sorts of topics, from curriculum design to memory and retention, but please, don’t ask me what to teach.