Education

The Land Where Angela Davis Is Queen

I have watched the culture here slowly change—the troubling values I fled so far from followed me like a sort of reverse Manifest Destiny.

In the immediate aftermath of the Kyle Rittenhouse trial, the Chancellor and the Executive Director of the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at my alma mater, the University of California, Santa Cruz, issued a joint proclamation condemning the verdict. It began with this:

We are disheartened and dismayed by this morning's not guilty verdict on all charges in the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse. The charges included fatally shooting two unarmed men, Joseph Rosenbaum and Anthony Huber, and wounding Gaige Grosskreutz at a Black Lives Matter rally in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in August 2020. We join in solidarity with all who are outraged by this failure of accountability.

They go on to offer counseling services for students, faculty, and staff who felt they had been traumatized by the legal verdict.

The Rittenhouse trial coverage had been the final piece of evidence that I could no longer trust the media outlets I’d come to respect. As a life-long liberal, and later, self-described “progressive,” and now, I guess, “classical liberal,” my concerns had been building for several years as I saw online movements like #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter develop from tools for social solidarity into mobs. Exposing lecherous Hollywood producers and instances of police brutality had struck me as positive at first. But as mob justice became indiscriminate, I was distressed and chilled to see journalists and academics cowering in the crosshairs. The climate reminded me of how I had felt as an undergraduate in Santa Cruz. I decided to start looking for alternative points of view.

I read two distinct narratives of the Rittenhouse case—one in which a heroic young man was defending his community, and another in which a teenage white supremacist crossed state lines to commit mass murder. Neither of these stories rang entirely true, and I was glad to be able to find some nuanced discussion that attempted to contextualize Rittenhouse and his actions in terms of the flare-ups that have followed The Great Awokening. Rittenhouse has since admitted that his trip to Kenosha was a mistake.

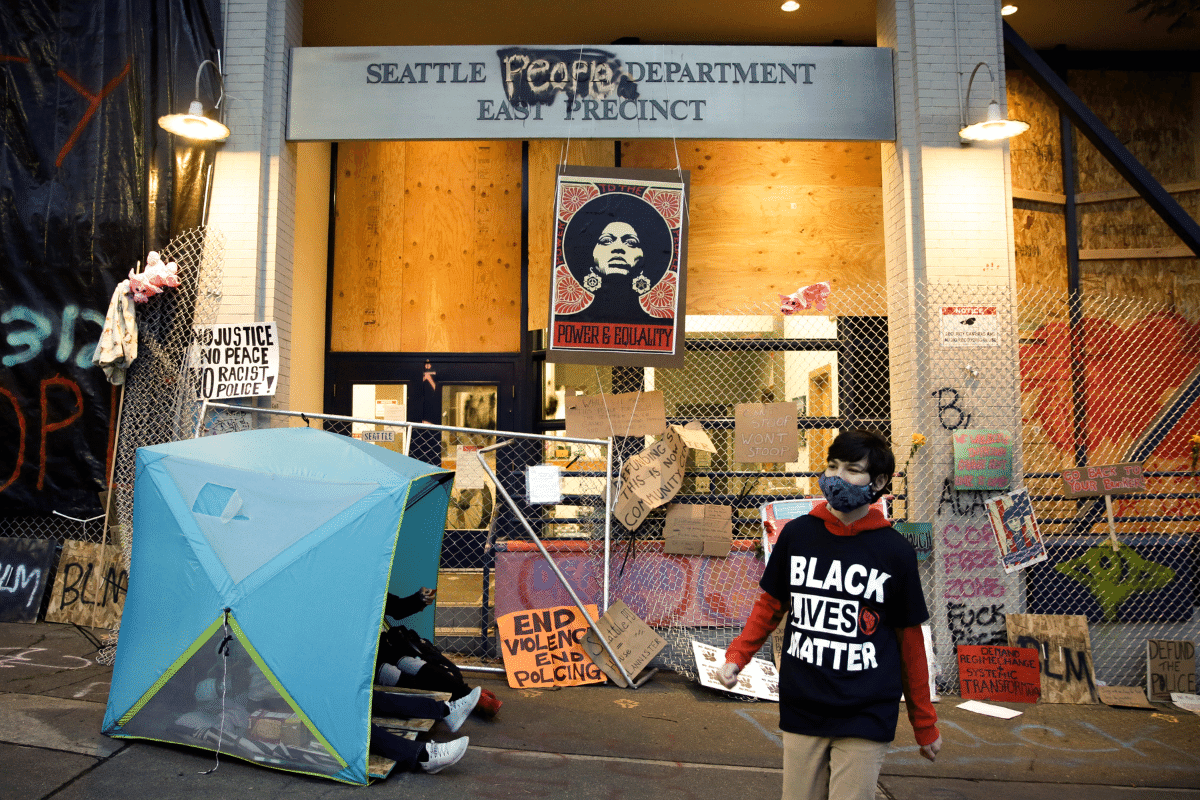

Last summer, I experienced another flashback to my time at UC Santa Cruz as I watched the coverage of what came to be known as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ), established in Seattle by Black Lives Matter protesters. The iconography that appeared throughout the encampment also reminded me of the fundamentalist religion in which I was raised. Black victims of police brutality like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were being portrayed as martyrs, while intersectional feminist activists like the late bell hooks (a UCSC alumna) were elevated to sainthood. Front and center was the patron saint of them all, Angela Davis.

I matriculated at UC Santa Cruz from 1995–1999. Angela Davis had been fired from her position at UCLA in 1969 due to her membership in the Communist Party, and was made a professor at UCSC in 1991. Over the next few years, she had become the star professor on campus with a cult-like following in the grandly named “History of Consciousness” department. The most notable graduate of “Hist Con” remains the late Black Panther Party founder Huey Newton.

I didn’t know much about Davis before I arrived on campus. I was a poor white kid and a former Jehovah’s Witness from Sacramento, and the only member of my immediate family to go to college. I remembered having heard Davis’s name as a punchline in Eddie Murphy’s legendary 1983 stand-up special Delirious, which I loved as a teenager. And I vaguely knew she had something to do with the Black Panthers, probably from watching the 1990 documentary, Berkeley in the Sixties.

I arrived on campus in 1995, aged 17, with the goal of becoming a screenwriter. No doubt, this dream had something to do with it being the '90s when independent film was all the rage. Also, I had fallen for a boy in high school who had a similar dream, and who worked at our local independent movie theater. However, I think my inclinations probably had more to do with the feeling that I had a message for the world—a product of my early formative years when I was socialized to be a missionary.

Jehovah’s Witness children are discouraged from going to college—partly to avoid the dangers of secularization, and partly because the long-promised (and overdue) apocalypse made such pursuits a waste of time. And, unlike our Mormon cousins, we don’t have a university of our own. If my mother hadn’t left the religion when I was 10 years old, it is unlikely that I’d have gone to college at all. I was an academically gifted kid, skipped a grade, and excelled in school, so I am grateful that life (and gifted and talented programs) conspired to open higher education to me.

Jehovah’s Witnesses are apolitical, but my mother (who joined the religion in her 20s) had been a hippie in the '60s. She had also, like me, been a bright student and skipped a grade. However, unlike me, she was raised in a sexually abusive home and got pregnant at 17 in order to get away from her family. She wasn’t in San Francisco for the Summer of Love in 1967, but she wanted to be. Instead, she was 90 miles away in Sacramento, watching it unfold on TV with my oldest brother, who was just a toddler. She was 20 then and retained some of her leftist ideology when she began studying with the Jehovah’s Witnesses in her mid-twenties. As Jehovah’s Witnesses, we didn’t vote or salute the flag, but my mother hated Ronald Reagan, and secretly campaigned for Jesse Jackson and his Rainbow Coalition in 1984.

So, when I discovered “worldly” politics, I was a liberal. California, of course, is now an overwhelmingly liberal place, but the agricultural Central Valley, where my mother’s family stretches back five generations to the Gold Rush, is an exception to that rule. And before the ascendancy of the Baby Boomers, California was a Republican stronghold from 1952–1988. Sacramento, being the seat of government, is politically divided, but my mother blamed Reagan’s governorship for all the terrible things that befell our family and for her precipitous drop in social standing. In my child’s mind, if liberal was good, then more liberal was even better.

The University of California, Santa Cruz is a land grant university situated on Monterey Bay overlooking the Pacific Ocean in the foothills of the Santa Cruz mountains, 75 miles south of San Francisco and just over the hill from what is now Silicon Valley. The campus sits on high in a forest, apart from the city of Santa Cruz, creating a distinct “town and gown” divide. I didn’t visit the campus before I applied, so when I arrived its natural beauty stunned me. Everyone seemed high on it (although the ubiquitous dazed countenances could also have been due to the potent weed that was everywhere, or the ancient, towering conifers pumping us full of oxygen like the patrons in a Las Vegas casino).

Eight of the 10 University of California campuses—Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Riverside, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, and San Diego—were deemed “Public Ivies” by Yale admissions officer Richard Moll in his guide to America's best public universities. Due to its quality and sheer size, the University of California is considered one of the best educational systems in the world, and currently, the best education system in the country, public or private. The Santa Cruz campus, however, has always marched to the beat of its own drum.

I had heard rumors of UC Santa Cruz’s eccentricities, which turned out to be mostly or somewhat true. For instance, I was told they didn’t have grades. This was the case from the University’s inception in 1965 through the first couple of years I was there. Up to that point, UCSC used a pass/fail “narrative evaluation” system. In 1997, the university gave students the option for letter grades in all classes and I remember the controversy the change ignited. In 2000, the year after I graduated, the faculty voted to require letter grades in all classes, and narrative evaluations were phased out in 2010, though some professors still choose to write them. I was also told the campus was “clothing optional.” Not entirely true, but there was (and apparently still is) a tradition of “First Rain” (rainfall is a rare novelty for Californians), wherein students strip naked on the first wet night of the fall semester and streak across the campus. I somehow always missed this spectacle, which the University has since condemned.

I had heard there was no Greek system. Also not entirely true, but it was hardly existent during my time there. There were no fraternities or sororities at UC Santa Cruz until 1987, and they remain an insignificant feature of campus life. I was also told there was no football team, no sports at all except “Ultimate Frisbee.” Not true, but close. There were no intercollegiate athletics until 1980 when Robert Sinsheimer, who was Chancellor from 1977–1987, introduced a series of reforms in an attempt to make UCSC a more conventional university.

It was Sinsheimer, a biophysicist, who paved the way for the first letter grade options. He also oversaw the creation of the computer engineering department (as Santa Cruz is a stone’s throw from Silicon Valley) and got UCSC to join the NCAA Division III. He suggested the native sea lion as a potential mascot, but the student body chose the Banana slug, a yellow indigenous gastropod, instead. The university’s motto “Fiat Lux” (“Let there be light”) then became, colloquially, “Fiat Slug” (“Let there be slug”). In the ‘90s, much like Greek life, sports were around the margins, but not much a part of campus culture.

I was also told that the campus was built to house the scholars who were too radical for Berkeley following the Free Speech Movement, which dominated the 1964–65 school year at Cal. The story went that the Santa Cruz campus was built in a decentralized way in order to keep students from having a place to organize and protest as they had at Berkeley. This history is a little bit more complex.

In 1952, Clark Kerr became the first chancellor of UC Berkeley. He presided over changes that made the University of California a distinct entity from its flagship campus at Berkeley. When Kerr later became president of the University of California, he turned it into a true university system. The campuses at Davis, Los Angeles, Riverside, Santa Barbara, and San Diego were already colleges or research centers and were then acquired by the fledgling University of California. They became UC campuses throughout the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Due to population demands, there was a push for a new campus south of Berkeley in the Monterey Bay area. San Jose and Santa Cruz were both vying for the spot, and in the end, natural beauty prevailed over practicality and Santa Cruz won out. Because the campus was so remote, it was conceived as a residential college where most students would live on-campus.

UC Santa Cruz is currently comprised of 10 small colleges. When I was there, there were eight: Cowell, Stevenson, Crown, Merrill, Porter, Kresge, Oakes, and College Eight. (Colleges Nine and Ten were still under construction.) College Eight has since been named Rachel Carson College, in honor of the author of the environmentalist classic, Silent Spring. College Nine remains College Nine. And, as of this year, College Ten has been named John R. Lewis College by the current Chancellor, Cynthia Larive, in honor of the recently deceased congressman and civil rights leader. I am inspired by Lewis’s advice to “Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and redeem the soul of America.” The “core course” of this college is “Social Justice and Community.” Its café is named for Terry Freitas, an alumnus who died in Columbia in 1999 fighting for the rights of indigenous people, and its three residential houses are named Angela Davis House, Ohlone House (for the indigenous Americans of the region), and Amnesty House, a tribute to the human rights work of Amnesty International.

The Santa Cruz campus is comprised of smaller, cooperative colleges, inspired by the Oxbridge system. The UC Irvine campus was conceived similarly, whereas the campuses at Davis, Los Angeles, Riverside, Santa Barbara, and San Diego followed Berkeley’s earlier model of a large college of letters housing the arts, humanities, and sciences. Construction on the Santa Cruz campus began in 1964, and the university opened the following year, still very much a work-in-progress.

In his two volume memoir, The Gold and the Blue: a Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Kerr discusses what he considered the many mistakes he made at the inception of UC Santa Cruz. As a graduate student at Stanford, he had been roommates with Dean McHenry, who became the first Chancellor of UCSC. The two men wanted to create a major research university with the feel of a small liberal arts college—several small liberal arts colleges or “Swarthmores,” in fact. They called this concept the “Santa Cruz dream.” But Kerr later lamented the timing of the campus’s opening, which coincided with the rise of the 1960s’ counterculture, and UC Santa Cruz quickly became Kerr’s problem child. In 1967, Ronald Reagan became governor and terminated Kerr for his handling of the student uprisings.

In 1969, Kerr came to deliver the first commencement address at UCSC, and a group of student protesters hijacked the ceremony. They attempted to award an honorary degree to Huey Newton who had been in prison since his 1968 conviction for the voluntary manslaughter of a police officer. Newton went on to receive his PhD from UC Santa Cruz in 1980. His dissertation was entitled, “War Against the Panthers: A Study of Repression in America.” The student protestors accused Kerr and McHenry of having “planned and created Santa Cruz as a capitalist-imperialist-fascist plot to divert the students from their revolution against the evils of American society and, in particular, against the horrors of the Vietnam War.” These were the echoes of conspiracy I heard in the campus lore when I arrived in the ‘90s. Kerr later wrote that the University had instantaneously become synonymous with the counterculture, as evidenced by the still-pervasive cannabis culture and comprehensive Grateful Dead Archive. He also feared that he had created a breeding ground for radicals.

In 2005, a group called “Students Against War” organized a protest at a UC Santa Cruz campus job fair where military recruiters were to have a presence. The students were well-organized, with “moles” inside the event, two-way radios, and hundreds of supporters mobilized. “Racist! Sexist! Antigay!” they chanted, “Hey recruiters, go away!” While I remain convinced that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were waged under false pretenses, this was not their principal protest. Rather, they objected to the American military’s masculine culture and accused it of preying upon minority communities. A melee broke out and the recruitment officers’ tires were slashed. Student protesters who were interviewed about the conflict boasted about how Santa Cruz had officially eclipsed Berkeley as the center of student activism. Later that year, it emerged that the Pentagon had surveilled the student protesters and deemed them a “credible threat.”

When I first arrived on campus in the mid-'90s, I was immediately struck by how white it was. My relatively wealthy public high school had been very white compared to the rest of my childhood, but this place was even more so. When I was a Jehovah’s Witness, a large proportion of our congregation was black, including my godmother and my mother’s first boyfriend after my parents divorced (when I was four years old). As a child, half the adult men who came into and went from my life were black.

Most of my childhood was spent in sprawling apartment complexes in lower-middle-class neighborhoods populated by working families, with a high proportion of white, black, and Mexican American single mothers, as well as many recent immigrants from Latin America, Southeast Asia, and the former Soviet Union, many of whom were fleeing Communist regimes. My college campus was shockingly rich and white by comparison. I quickly learned that the overwhelming majority of my fellow students were also from California, but most of them were from the more affluent greater Los Angeles suburbs or the San Francisco and Monterey Bay areas. There were very few kids like me from the Central Valley. When I told people I was from Sacramento, I usually got one of two withering responses: “Oh, I stopped there once on the way to Tahoe” or “It’s so hot, I don’t know how anyone can live there.” The university now seems to have significantly more Latino and Asian students than when I was there.

It quickly became a joke among us in the dorms that every course title ended with the words “…and race, gender, and sexuality.” This was especially true for those of us in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. I found it intriguing and somewhat amusing that the richest, whitest place I had ever been was also what would today be described as the most “woke,” but in those days would have been called “politically correct.” I had grown up around religious and secular working- and middle-class people of many races and ethnicities and I knew them to be more conservative than my ex-hippie, second-wave feminist mother, and certainly more conservative than these academics who struck me as a little nutty and out of touch.

Once I concentrated my studies in the arts and humanities, the graduate assistants who led my discussion groups and graded my papers were largely students of Angela Davis in the History of Consciousness department. They were mostly white and had lots of tattoos, piercings, and Manic Panic hair colors. They were also largely gay or lesbian or identified as “queer.” This was quite a while before the “Q” had officially been added to GLBT (the G used to be first), and the last I had heard, “queer” had been considered offensive to people like my gay uncle and my gay and lesbian friends in high school. That is when I was taught the term “reappropriation,” and discovered that “queer” identity was born at the intersection of French poststructuralism, feminist theory, and the activist movement that emerged during the AIDS crisis. I also discovered that “queer theory,” championed by occasional visiting professor Judith Butler, wasn’t really about GLBT people gaining the same rights and protections as heterosexual people, it was about destroying “the patriarchy” and gender norms entirely.

That last part never sat well with me. While I was (and remain) broadly supportive of diversity and tolerance, the destruction of all norms seemed a bit, well ... destructive. I liked the idea of marrying a man someday and having children. My mother had never had a functional domestic partnership, but I was lucky to meet some happy nuclear families when I started hanging out with my new friends. Deep down, I wanted that for myself. And I wanted my children to have the father I didn’t get to have—I still craved paternal love and guidance and chased it through mentors and lovers throughout my life. But according to this “queer” worldview, my desires seemed downright regressive. But I kept this to myself, wondering if I had been brainwashed by the patriarchy.

“It’s not my fault! It’s not my fault! It’s not my fault! It’s not my fault! IT’S NOT MY FAULT!” I gazed around the lecture hall as hundreds of women rose to their feet, whipped into a frenzy, screaming this refrain with their hands in the air. I felt compelled to get to my feet too, much as I had stood out of respect while others saluted the flag when I was a young Jehovah’s Witness. But I didn’t join the chanting because I didn’t know what “it” referred to. We had been in the middle of a lecture when our professor, Bettina Aptheker, suddenly started to repeat these words calmly and slowly, gradually building in intensity, until the crowd began to join in. Young women wept and embraced one another, continuing to scream, fists in the air, while I looked around in awe and confusion.

This was “Intro to Feminism,” which I took in the fall of my senior year. Like Angela Davis, Aptheker was one of the megastars on campus. Davis and Aptheker were both members of the Communist Party and long-time friends. Aptheker had worked for the defense in Davis’s high-profile 1972 trial for conspiracy, murder, and kidnapping. She later wrote a book about the case entitled The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis, first published in 1975. Aptheker obtained a PhD from the History of Consciousness department in the early ‘80s, around the same time Huey Newton was there, and she immediately joined the faculty, ultimately heading the women’s studies department.

A few years later, I watched the 2012 documentary Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, in which Aptheker was a prominently featured interviewee, and I decided to find out about how her life had played out since I graduated. I learned she had written a memoir, Intimate Politics: How I Grew Up Red, Fought For Free Speech, and Became a Feminist Rebel, published in 2006, and suspected that she may have been working on it around the time I was in her class. I was curious, so I bought it.

Aptheker writes about growing up as a “red diaper baby” raised by members of the United States Communist Party. Her parents were both Jewish activists who were part of a large community of Communist and progressive New York intellectuals and artists. W.E.B. Du Bois was a family friend, for whom the young Bettina later worked. Her mother, Fay, was a union organizer and 10 years older than her husband. Her father, Herbert Aptheker, was a blacklisted Marxist historian who testified during the McCarthy trials. He is best known for a seminal book about African American slave revolts and went on to become a significant figure in shaping what became the study of black history in America.

In her book, Aptheker also writes briefly about her father’s scholarship, offering an important critique. “He accurately reported betrayals in his writings, for example, in slave revolts,” she writes, “but in lectures he represented the history as one of undaunted heroism." This, she explains, was a naïve and condescending point of view, and one that could only be held by an outsider who did not understand the complexity of the black American experience. (I see similarly reductive views of history concerning issues of race in our contemporary discussions about “anti-racism.”)

The most significant section of Aptheker’s memoir, though, is her graphic description of being sexually molested by her father between the ages of three and 13. She says she began writing the book in 1995, but that the memories of sexual abuse only started resurfacing in 1999 while I was taking her classes at UC Santa Cruz. Critics of her memoir have questioned the veracity of these repressed memories, in view of the suspicion with which recovered memories of childhood abuse are now treated in the aftermath of the Satanic ritual abuse crisis during the 1980s.

Recalling the “it’s not my fault” spectacle, I wondered if the “it” to which the women had referred was sexual abuse. I saw my mother, the incest survivor and subsequent rape victim many times over, in the anguish they had broadcast and reflected in one another. The lecture had not been about sexual abuse, but that was the subtext I now inferred. In a room full of hundreds, no doubt some of these young women were victims. But I have not been the victim of sexual abuse or rape (something for which I give my mother a lot of credit), so I was confused during the incident. Hysteria had possessed the room within seconds, and certainly not all these young women were the victims of abuse. It occurred to me that they may have been referring to the very condition of being a woman, something I have never felt to be an affliction.

Aptheker was warm, intensely likeable, and had a mischievous sense of humor. She didn’t strike me as particularly ideological. She had lived a remarkable life though, and I still feel privileged to have taken her class. As I reflect now, I see she was going through an intensely painful personal reckoning when I encountered her. Her class felt like group therapy, in some good and also very bad ways. I had the thought while encountering those ideas that “women’s studies” perhaps shouldn’t be in its own ideological ghetto but woven into the other disciplines in more thoughtful ways.

Aptheker merits a glancing mention in Joan Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem in an essay called “On Keeping a Notebook.” Didion, a Sacramentan like me and a Cal alumna like Aptheker, says only that Bettina was one of many counter-cultural figures of the era who made an impression on her. I stopped when I saw her name, though, as I read the collection of essays shortly after college. Aptheker had also made quite an impression on me. Slouching Toward Bethlehem had a profound impact on me as well, as I saw in Didion’s titular essay (an expose about the dark side of the counter-cultural movement in Haight-Ashbury) the two people who had raised me, both of whom would end up drug-addled, broke, and alone. The downstream consequences of the counterculture movement—drugs, divorce, and social destabilization—destroyed my already damaged parents.

I took two other classes that quarter, with two other significant campus figures: “Suspense Fiction” with Earl Jackson, Jr., and “Personal Computers in Film and Video” with Chip Lord. These classes informed each other and my later trajectory. Earl Jackson, Jr. enjoyed a cult-like following in the Modern Literature department, and the hipster kids (who we called “emo” back then) followed him around like groupies. His classes were considered the most cutting edge in terms of literary criticism, and I was curious. At the time, he was at the height of his career, with the 1995 publication of Strategies of Deviance: Studies in Gay Male Representation. He was in the Literature Department, but his work also ventured into film theory and criticism. I had taken many of those sorts of classes, so I had already encountered Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalytic theories, Foucault, Derrida, semiotics, and the then-nascent “queer theory” that informed his scholarship.

The Suspense Fiction syllabus consisted of hard-boiled pulp fiction novels by Jim Thompson, the misanthropic works of Patricia Highsmith, and several zines, cyberpunk novels, and postmodern memoirs of lurid sexual escapades written by Jackson’s San Francisco friends. I was by turns amused, titillated, and horrified by a lot of what we read. I was a savvy enough kid to recognize the coup he was pulling off in getting hundreds of rich kids to buy his friends’ smut every year. But I struggled to find a theme among the books we studied other than their brutal depictions of violence against women. He liked one of my papers and invited me to his office, which I was told was a big compliment.

When I dropped by, I immediately noticed how dirty it was. We discussed my paper, which I knew was well-reasoned but essentially gobbledygook, and our conversation seemed to impress him. My family’s agriculture business had trafficked in bullshit for generations, so I was good at this. He asked me what other classes I was taking and when I said, “Personal Computers in Film and Video,” he replied, “Interesting.” When I added “…and Intro to Fem,” he rolled his eyes and waved his hand dismissively. With a sigh, he said something like, “You just have to nod and give them what they want.”

Chip Lord was the closest thing I had to a mentor at UC Santa Cruz. He is best known for his involvement in a Bay Area avant-garde art collective in the late ‘60s and ‘70s called Ant Farm. He taught the Personal Computers in Film and Video class I took that fateful semester and was an advisor for the two 16mm films I made while I was there (one of which was my thesis). He was a generous, even-tempered, and patient professor, who took a liking to my work. Upon graduation, he recommended me for a project with a UCSC sociology professor (a young woman) who wanted to make a documentary about the history of nuclear testing in the Bikini Islands. I was insecure about my technical abilities, however, and did not pursue the opportunity.

When I told him I was moving to San Francisco after graduation, he tried to get me a job with some friends who had a post-production studio, but computer editing was not a particular strength of mine, and it only paid $8 an hour which was not enough to live on in San Francisco at the height of the dotcom boom. I was very grateful for all he tried to do for me, but after nine miserable months in San Francisco, I realized it wasn’t the place for someone like me to live the life of an aspiring writer. You had to have rich parents for that.

Since then, I have spent my young adult life in New Orleans with a fellow UCSC alum, whom I met down here when we were both lost kids from northern California working in bars and restaurants. He moved here in 1993 on a similar trajectory. When I arrived in 2000, it felt like an ex-pat community. The locals were warm and friendly and had the wisdom and common sense that often comes from having faced real adversity (and the humor and levity that you must develop in order to survive it). It felt like the closest thing to living in a traditional culture that I had found anywhere else in the country. Indeed, people often call New Orleans “the northernmost Caribbean city.” In some ways, it reminded me of my Jehovah’s Witness community. It was close-knit, welcoming, and largely black. Eventually, my now-husband and I bought our first house in New Orleans just days before Hurricane Katrina, fulfilling my life-long dream to have a home of my own after getting priced out of my home state of five generations. I gave birth to our son in its living room seven years later.

But over the years, I have watched the culture here slowly change—the troubling values I fled so far from followed me like a sort of reverse Manifest Destiny. After Katrina, waves of Millennials, a bit younger and lot more earnest than my husband and me, arrived on a mission to fix the broken city. These young people came armed with expensive degrees from universities now permeated with UCSC’s ideology. They also came with seed money for non-profits and co-ops. Even younger white anarchists—all tattoos, colorful hair, and “gender queer” like my Santa Cruz TAs in the ‘90s—came next. They are the ones who started to deface new businesses and condos under the auspices of “fighting gentrification,” when these were often businesses and developments popular with the middle-class black population who constitute the city’s majority. Others came with the Teach for America program, slowly replacing native-born black teachers in the city’s school system, which was taken over after the storm. The district became an all-charter system in an attempt to reform and reintegrate the schools. This was a familiar scene, much of which I had watched play out in San Francisco and Oakland two decades earlier.

My son, who is white, is in the fourth grade at a charter school, the core mission of which started out as “creating innovators” but, following a change of leadership, is now dedicated to “advancing equity.” Black Lives Matter posters are suddenly everywhere. Lately, the school has a few Latino and Asian kids but, like New Orleans, is still pretty much 60/40 black/white. Not long ago, they hired a “Director of Culture” whose title immediately struck me as a bit Maoist (I tend to believe that culture emerges and resists being “directed”).

As I had in Santa Cruz, I hung back, watched, and kept my observations to myself. That is, until the other day. My husband went to collect our son from school, which has become an impenetrable fortress in the age of gun violence and COVID, and was greeted by the new Director of Culture, a young black man from Chicago wearing a t-shirt bearing an image of UCSC’s favorite son, Huey Newton, holding a rifle.

I decided to re-watch Free Angela and All Political Prisoners. Nearly a decade ago, its unapologetic presentation of Angela Davis as a hero and political prisoner had unsettled me. But now I saw a more complicated narrative, not altogether dissimilar to the complicated narrative I pieced together about the Rittenhouse incident once I had cleared a path through all the polemics. I saw in Angela Davis a brilliant young woman born of considerable privilege in the context of her community. I also understood her righteous rage at the horrible conditions of segregated Birmingham. I saw a young woman who allowed herself to be seduced by a dangerous ideology. I saw someone too young for the pressure to lead her people and blinded by her love for an incarcerated revolutionary. When confronted with this part of her story, I could see regret in the contemporary Davis’s eyes. I believe she knows she made a terrible mistake that ended in the death of four innocent people, including her beloved’s kid brother.

And yet, the film ignores the injustice of those deaths, and the pain of their families. And though Angela Davis ultimately left the Communist Party, she remains the ideological root of the Defund the Police movement, and the rhetorical assault on law enforcement that is allowing the cities of San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, and Minneapolis to implode. This is the culmination of her life’s work.

The other day, my family and I walked our elderly dog along a stretch of the Mississippi River known to locals as “the end of the world.” My husband and I hadn’t been back there since we were priced out of the neighborhood, and I was taken aback by how much it had changed. I didn’t see any images of Angela Davis like those that appeared in Seattle, but her influence was palpable. Nihilistic political graffiti had proliferated (“YEEHAW FUCK the LAW”) and a sign scrawled on the decommissioned naval base informed us that it is now “The New Orleans Autonomous Zone.” My son asked me what “ACAB” means.

In October, a local non-profit called the Metropolitan Crime Commission reported that the homicide rate in New Orleans has shot up to 12 per 100,000 residents since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Not only have nonfatal crimes similarly increased during the period,” the report added, “but New Orleans District Attorney Jason Williams has declined to pursue many alleged crimes.” As we picked our way through the hypodermic needles littering the river levee, and watched people who were clearly mentally ill rummaging through the “free store” established by the anarchist community that squats there, I paused for a moment and surveyed the scene. I turned to my husband and said, “It’s time for us to move again.”