Review

Revisiting ‘Wake in Fright,’ A Peculiarly Australian Kind of Hell

Five decades after its release, Wake in Fright remains a brutally captivating reminder that modernity is just a thin veneer over the darker recesses of the human heart.

Watching director Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 psychodrama Wake in Fright 50 years after its initial release somehow evokes the irrecoverably distant and the hauntingly familiar. In one respect, the film’s desolate setting and suffocating atmosphere of violent desperation are so far removed from the urban, multicultural experience of Australia today that it’s hard to believe it’s the same country a mere two generations ago.

Nevertheless, the film retains an eerie familiarity—it still represents something quintessentially Australian. The gambling is as pervasive as ever; the punishing heat and the outback, of course, remain; and while beer and tobacco consumption have declined, their substitution by other forms of vice shows that we haven’t tempered our appetites, merely transformed them. Wake in Fright, observed the late American critic Roger Ebert in 2012, had not dated since its release in 1971. “It is powerful, genuinely shocking and rather amazing. It comes billed as a ‘horror film’ and contains a great deal of horror, but all of the horror is human and brutally realistic.”

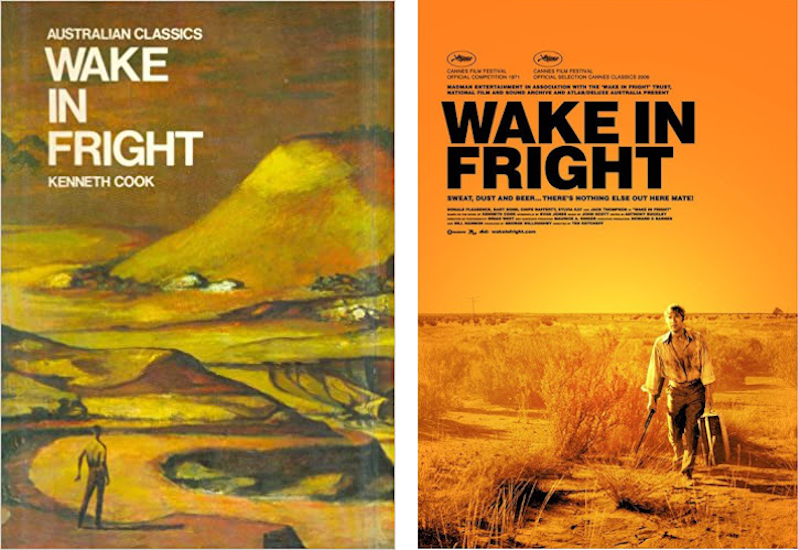

The film is based on Kenneth Cook’s 1961 novel of the same name, the title of which seems to have been lifted from a poem by a 19th century English cleric named Richard Harris Barham. When a jackdaw steals a cardinal’s ring, Barham tell us that the cardinal sought to avenge the theft with a spell:

He cursed him in sleeping that every night,

He should dream of the devil and wake in a fright.

Kotcheff’s screen adaptation faithfully retells Cook’s story of a young man’s descent into a peculiarly Australian kind of hell. Returning home for the school holidays, Sydney-bred teacher John Grant gambles away all his money during a layover in the remote outback mining town of Bundanyabba—or “the Yabba” as it’s better known—and finds himself stranded there. It’s a modern Sophoclean tragedy about the ancient notion of hubris, transposed from a Hellenic to an antipodean locale. And yet, the result is a film that could hardly be more Australian. As Kate Jennings remarked in a 2009 essay, it is “one of those rare movies which captures the spirit of a country” and tells “a larger truth about a nation’s collective psyche.”

The Yabba and its inhabitants are thinly disguised substitutes for the New South Wales mining town of Broken Hill, which provided Kotcheff with the film’s exterior locations and many of its extras. It also served as the direct inspiration for Cook’s novel. In the book, Cook described the Yabba as the kind of place where “a man felt he had either to drink or to blow his brains out.” Paradoxically, the outback’s vast expanse oppresses as much as it liberates. By way of illustration, Jennings invokes expatriate author Alan Moorehead’s remark that “one of the fascinating things about Australia is this sense of claustrophobia in the midst of such an infinity of space.” The inhabitants of the Yabba are products of this unforgiving environment.

The novel was inspired by what Cook describes as his own “traumatic experience” of Broken Hill as a young journalist, and he only renamed the town and its inhabitants to avoid the possibility of litigation (the threat of which had sabotaged his first book). “Each [character],” he recalled, “was nothing less than a libelous attack on a real person.” In a 1972 interview, Cook stated:

[Broken Hill] first started my definite hate relationship with what I think of as the gross violence—the mindless violence—of one section, in fact I think the major section, of the Australian scene. I was, you know, very strongly impressed with Broken Hill—hated the place, hated the people, hated the atmosphere, hated the environment, hated the whole thing. And this hatred finally sort of popped out as Wake in Fright some eight-to-ten years later.

These sentiments are confirmed by those who knew Cook, including his second wife and fellow writer, Jacqueline Kent:

Ken had a real love/hate thing for the bush … I think he had a romantic idea of the bush and the outback himself but the experience of it left him disappointed. He was aching to get out into it but the people he found there he felt were mean and nasty and the writing of Wake in Fright came out of that tension.

In the novel, Cook describes the predicament faced by his protagonist and alter-ego Grant as follows:

…an outcast in a community of people who were at home in the bleak and frightening land that spread out around him now, hot, dry and careless of itself and the people who professed to own it.

The story is not only semi-autobiographical, but also highly symbolic—the Yabba is a synecdoche for the untamed wilderness in which Grant, a naive but arrogant representative of modern civilisation, finds he must adapt or perish. But it also serves as an exploration of the social chasm between the urban and the rural, the professional and the menial, the educated and the ignorant—a bitter Hobbesian rebuke to Rousseau’s facile theorizing about our innate natural nobility. This is not the mesmerising idyll portrayed in Nic Roeg’s poetic film Walkabout, which was released the same year as Kotcheff’s film; it is an alien territory fraught with danger and peopled by menacing mediocrities. It may also be read as an indictment of the colonial settlement of Australia and its consequences. Immigrants from northern Europe found that they could—with a lot of civilizational armory—survive in the outback’s desolate inferno, but Cook makes clear that the costs of that experience for those involved have been steep.

For a film that’s so thoroughly Australian, what’s surprising is that many of the key figures involved in its production were not. The early drafts of the script were written by Jamaica-born English screenwriter Evan Jones, who had never set foot in Australia and wouldn’t do so until a decade and a half after the film had been produced; the American expat and communist Joseph Losey (then living in England where he fled to avoid the attentions of the House Un-American Activities Committee) was attached to direct; and British actor Dirk Bogarde (with whom Losey had previously worked on The Servant and Accident) was originally picked to star. Given the novel’s success, a rapid transition to the screen was expected to be a mere formality. As writer and filmmaker Peter Galvin remarked in his lengthy series of essays on the film’s gestation, “Wake in Fright seemed written to be filmed. It had little dialogue, a strong atmosphere, a picturesque location, unique characters, [and] an intensely dramatic situation.” It was, Jones remembers, “a natural screenplay.”

However, the rights lapsed due to assorted delays, and it wasn’t until 1969 that production finally began. The film was eventually financed by an Australian-American consortium and produced by a Norwegian-born Briton named George Willoughby. After Losey dropped out, Ted Kotcheff—the Canadian son of Bulgarian immigrants—was chosen to replace him. Kotcheff would later find commercial success with First Blood (1982) and the black comedy Weekend at Bernie’s (1988), but in 1969 he was hired on the basis of his critically acclaimed 1969 British film Two Gentleman Sharing, a story about an inter-racial gay couple, also scripted by Evan Jones.

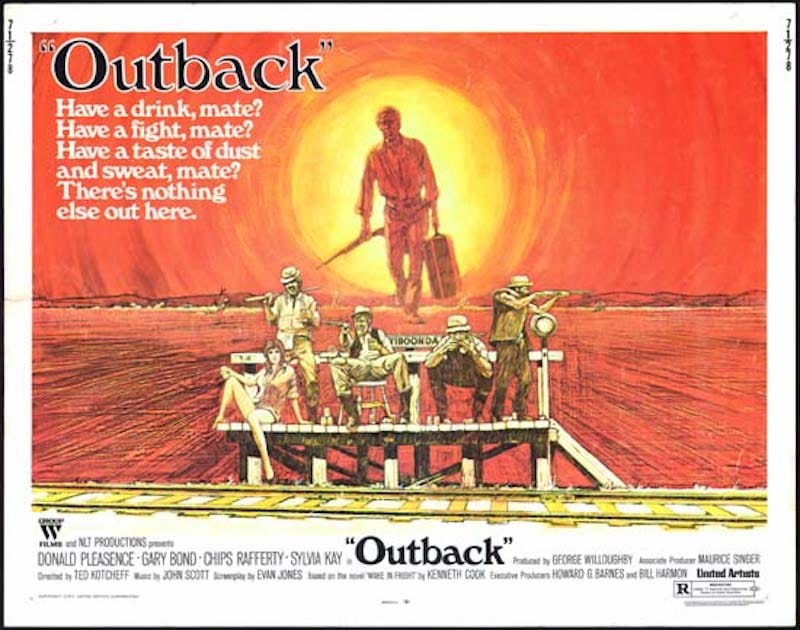

Three of the key roles were filled by British actors with scant experience of Australia: Kotcheff’s then-wife, the English actress Sylvia Kay, was cast as the sexually frustrated Janette Hynes, the film’s only major female role; Gary Bond—a blond English actor who bore more than a passing resemblance to the young Peter O’Toole—was cast as John Grant after the part was turned down by a number of more famous names; and Donald Pleasence—then an acclaimed British stage actor best known to the movie-going public as James Bond’s nemesis Blofeld in You Only Live Twice—was picked to play the parasitic alcoholic, Doc Tydon, who latches onto Grant upon the latter's arrival in the Yabba.

The rest of the cast was Australian—Broken Hill native Chips Rafferty was chosen to play Constable Crawford in what would be his last screen role, his nuanced performance and immense physical presence providing one of the film’s highlights. And Jack Thompson, who would go on to appear in the Australian classics The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978) and Breaker Morant (1980) as well as a number of Hollywood hits, was handed his first part as one of the town’s thuggish miners.

Kotcheff and Kay landed in Australia with their family in late 1969 to scout locations and start pre-production, and principal photography began at the height of the sweltering Australian summer in early 1970. “There was only one way to make Wake in Fright, given the $800,000 budget,” notes the film’s assistant-director, Howard Rubie, “and that was to do 90 percent of the interior work on the film in studios or locations in Sydney and shoot just about all the exteriors in Broken Hill.”

So, the iconic scene in which Grant encounters Crawford amid a throng of miners in a large outback pub was actually staged in a bar beneath Sydney’s main sports-stadium, the SCG, with Grant surrounded by extras Kotcheff had sourced from a labor exchange. The film’s other interiors, including Grant’s meeting with the dim-witted Tim Hynes, were likewise shot in Sydney. The Hynes’s outback home was a house in Killara, in the heart of north Sydney suburbia. The now-famous gambling scene, meanwhile, was shot in an abandoned warehouse in inner-city Paddington. The scenes set in Doc Tydon’s outback shed—the site of much of the film’s intrigue, including an implied male rape that deterred many of the actors offered the role of Grant—were recorded inside a purpose-built replica erected at the Bondi Junction studio.

Given these compromises, Kotcheff and the film’s (English) cinematographer, Brian West, went to great lengths to ensure authenticity. They procured sacks of the desert’s red dust to be scattered around the interiors, and thousands of flies—an omnipresent feature of the film—were sourced from a University of Sydney science lab and then released into the sets. West lit the picture to simulate the outback’s harsh sun, and (English) art director Dennis Gentle stripped the production’s design of greens and blues at Kotcheff’s request to accentuate the Yabba’s stifling desert ambience. “To recreate what I felt and saw—the heat, the sweat, the dust, the flies,” Kotcheff later remarked, “I said to the set designer and the costume designer, ‘I don’t want to see any cool colours. I don’t want to see blue or green. Ever. On anything. All I want is red, yellow, orange, burgundy and brown. All the hot colours. On costumes, sets, everything.’ I wanted people to watch the film and be unconsciously sweating.”

Kotcheff’s foreign origins undoubtedly helped illuminate many of the Yabba’s local idiosyncrasies that may have passed unnoticed by a more familiar eye, such as the summer Santa and the workings of the Australian RSL hall, replete with the minute’s silence and the dead glare of the poker machine. More importantly, he seemed to understand the locals better than Cook had: “[I admired] their fortitude in the face of the most inhospitable circumstances in the world to work and live in. I loved their camaraderie. I loved their humour, their generosity, and their support of each other. It was extraordinary.” So, while Cook’s contempt is barely concealed, Kotcheff’s vision is much more sympathetic.

Cook had been born and raised in Sydney, but Kotcheff’s familiarity with Canada’s own vast expanses helped furnish him with an intuitive understanding of rural life that was lacking in the novel. He worked hard as well, taking the time to familiarize himself with the locations, the inhabitants, and the customs (such as the uniquely Australian coin-toss game of “two-up”) which he would soon commit to film. He tried to refrain from passing judgement on his characters or moralizing about their bleak lives, preferring to let the action unfold under its own grim momentum before his impassive lens. In this respect, his approach recalls that of Anton Chekhov, whose story The Horse-Stealers Kotcheff cites as an inspiration. “I’m not the judge of my characters,” Kotcheff has said, quoting the Russian writer; “I’m their best witness.”

Notwithstanding this difference in attitude and approach, Kotcheff’s film is remarkably faithful to Cook’s book—much of the dialogue is lifted verbatim—and successfully communicates the sense of gathering menace and horror. The film’s notorious kangaroo hunt, which serves as the nadir of Grant’s descent into madness, remains a harrowing scene to this day, but it was an even greater ordeal to shoot. Kotcheff and his crew accompanied a group of hunters on a late-night cull, and the experience was so shocking that the crew quietly sabotaged the shoot to bring the carnage to a premature end. As Galvin reports:

“What I saw in the rushes was far worse than anything we put in the picture,” remembers [editor Anthony] Buckley. In one take a kangaroo was splattered in a particularly spectacular fashion. Watching this, [producer, George] Willoughby, on set to supervise as usual, feinted [sic] dead. According to camera operator Peter Hannan the killing went on for hours.

The stench, the blood and the obvious delight the 'Roo shooters had in their work started to wear down the filmmakers. Still, Kotcheff felt the pro hunters weren't exactly oblivious to the emotions being stirred up around them: “They would say to me: 'Ted we never look into the eyes of a kangaroo because if you look deep into the eyes of a 'Roo you'll never shoot one ever again.'”

It gets cold in the desert at night. The hunters started to hit the whisky to warm themselves. “By 2AM the hunters were getting really drunk and they started to miss,” says cinematographer Brian West. Wounded kangaroos were hopping about helplessly, trailing their intestines. “It was becoming this orgy of killing and we (the crew) were getting sick of it.” West had a private word with [his gaffer] Tony Tegg, who arranged a ‘power failure.’ “I told Ted that we didn't have enough light to continue.” The crew headed back to Broken Hill, some of them fighting back tears.

Principal photography wrapped in the autumn, and post-production was completed later that year at Pinewood Studios in the UK. The film then made its way to the 1971 Cannes film festival for its premiere, where it was seen by a young and then-unknown film director named Martin Scorsese, who later recalled: “Wake in Fright is a deeply—and I mean deeply—unsettling and disturbing movie. I saw it when it premiered at Cannes in 1971, and it left me speechless. Visually, dramatically, atmospherically and psychologically, it's beautifully calibrated and it gets under your skin one encounter at a time.” The New Yorker’s film critic Pauline Kael was also impressed: “You come out with a sense of epic horror,” she reported.

And then … the film sank, almost without trace. Despite an opulent opening at Sydney’s Embassy Theater, Wake in Fright disappeared from the city’s screens a mere 10 weeks after its opening, and from the rest of the country well before that. It was pulled from screens in Brisbane after just one week. Released internationally as Outback—studio executives worried that “Wake in Fright” sounded too Hitchcockian—the film’s public reception outside of Australia was scarcely better. The only place it found any real success was in Paris, where a subtitled British print of the film played for nine months near the Champs-Élysées under the title Reveil dans le Terreur. But that wasn’t enough to save it from commercial oblivion everywhere else.

In the ensuing decades, the only place one could watch Wake in Fright was on a handful of bootleg copies. Astonishingly, it was broadcast on Australian television just a handful of times in the late 1980s. By the 1990s, it had become known as a lost classic—a misunderstood and under-appreciated gem, ignored upon its release and since forgotten. It wasn’t until the negative was found in Pittsburgh in the early 2000s, that the film was granted a second lease of life and finally received the attention and acclaim it deserved. Asked in 2012 if he was surprised by the film’s reception 40 years after it was made, Kotcheff replied:

It's not a surprise, it's a miracle. It was declared dead and buried. They looked for it for about ten years and couldn’t find it. The Australian producer made inquiries but had no luck. Then my editor Tony Buckley, who loved the film, set out as a personal challenge to find it. He went to London where it had originally been processed. There was supposed to be a print in Dublin so he went there. He also went to New York. This was during a two-year period about five years ago. He finally found the negative in a warehouse in Pittsburgh. It was in two big boxes full of negatives, big prints, and soundtracks. And on the outside of the boxes it said, FOR DESTRUCTION. If he'd arrived a week later it would have been incinerated. The film had failed and now it rises from the dead. And this time it has succeeded.

Following a painstaking restoration process, Scorsese’s support helped secure a second screening at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, where he personally introduced it as part of the programme of “Cannes Classics”—it remains one of only two films to be screened at Cannes twice (the other is Antonioni’s L’Avventura).

What explains the profound neglect of a film praised by Ebert, Kael, and Scorsese, and feted at Cannes? It remains a deeply provocative and uncomfortable watch, but its brutal depiction of outback life may have proven particularly unpalatable to Australians. As Jack Thompson recounted years later, “I honestly don’t think Australians were prepared for the shock of it. We’d grown accustomed to this mythology that we were really just good blokes—‘you beauty, mate’ and ‘up the digger’—and the film presented us, for the first time, in a way that was direct, raw, and intimate.” Nick Cave has called it “the best and most terrifying film about Australia in existence.”

People even protested during the film’s first-run screenings. At an early exhibition of the film that Thompson attended, an audience member stood up and shouted, “That’s not us!” To which Thompson replied: “Sit down, mate. It is us.” It seemed to confirm many of the less flattering critiques of Australia, echoing what the Australian poet James McAuley wrote about his countrymen in the 1940s:

The people are hard-eyed, kindly, with nothing inside them,

The men are independent but you could not call them free.

In his masterful book, The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787–1868, cultural critic Robert Hughes observed:

Mateship, fatalism … harsh humour … disdain for introspection, and an attitude to authority in which private resentment mingled with ostensible recognition were the meagre baggage of values the convicts brought with them to Australia. They also brought, if men, the phallocracy of the tavern and ken, and, if women, a kind of tough passivity, a way of seeing life without expectations.

This jaundiced view was shared by Wake in Fright’s creator, Kenneth Cook. For Cook, the aggressive alcoholism, the mindless gambling, the casual violence, and the unrepentant anti-intellectualism are all variations on what Robin Boyd dubbed the Australian Ugliness. These tendencies were most pronounced in the country’s sparse rural areas, removed as they are from the moderating effects found in cities. Indeed, Cook’s view is eloquently summarized by Peter Temple in his wonderful introduction to the 2001 edition of the novel:

Cook will have nothing of what historian Richard White calls the “familiar iconography of outback Australia—the homestead, the sheep, the lonely gum, and the proud Aborigine.” For him, the place is a variation of hell.

And the ability to be at home in the “bleak and frightening land” is a flaw in the outback’s people. There is something wrong with them for enduring this harsh place. They are not the innocent victims of the lonely, arid land; they have made an unnatural choice to live in it that reflects their own stunted, even perverted, nature.

When Grant first encounters Doc Tydon at the two-up school, the film offers a rare moment of empathy for the plight of people surviving in such a desolate place. Tydon asks what rankles Grant about the Yabba. “The aggressive hospitality,” Grant replies impatiently. “The arrogance of stupid people who insist you should be as stupid as they are.” To which Tydon responds: “It’s death to farm out here. It’s worse than death in the mines. You want ’em to sing opera as well?”

So popular was Wake in Fright’s re-release that it resulted in a new edition of Cook’s novel and a two-part miniseries. It also refocused attention on Kotcheff, now in his 90s, and the important part he had played in the cinematic renaissance during the 1970s and ’80s that came to be known as the “Australian New Wave.” For New Wave directors like George Miller (Mad Max), Bruce Beresford (Breaker Morant), Fred Schepisi (The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith; A Cry in the Dark), and Peter Weir (The Cars That Ate Paris; Picnic at Hanging Rock), Kotcheff was an inspiration—the director who blazed the trail they’d soon follow.

At fifty years’ distance, Wake in Fright’s startling power and poignancy are undiminished. Brian West’s harshly beautiful aesthetic remains thick with threat and the performances Kotcheff elicited from his talented cast are riveting. Gary Bond captures the callow arrogance of John Grant’s incongruous urban everyman, while Donald Pleasence’s Doc Tydon, Chips Rafferty’s Crawford, and the town’s community of miners, exude that particularly Australian combination of congenial bonhomie, brooding hostility, and predatory malice. Kotcheff’s film also exhibits enough philosophical whimsy to further confirm its status as a cult classic. “Discontent is a luxury of the well-to-do,” Tydon tells Grant. “If you've got to live here, you might as well like it.” Tydon later offers a drunken Lear-like disquisition amid brawling miners and a comatose Grant: “Perfectibility? Progress? A vanity spawned by fear!”

And that is the key to the film’s enduring potency. While Wake in Fright is an enthralling, well-performed, and beautifully made film, it’s ultimately a faithful manifestation of its creator’s unsettling insight. Like Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (released the same year) and John Boorman’s Deliverance (released the year after), Wake in Fright is a cautionary tale about the fragility of civilization and our ineradicable capacity for savagery—a parable intended to show humankind in the most unflattering of lights with little in the way of redemption.

Kotcheff and Cook invite us to find in Grant’s Dante-esque disintegration a harbinger of our own decline—Grant is us, even if we’re unwilling to acknowledge it. Five decades after its release, Wake in Fright remains a brutally captivating reminder that modernity is just a thin veneer over the darker recesses of the human heart.