Sex

Can We Have Sex Back?

For a start, sex can be pretty delightful, and if you are a smart person (as many—though by no means all—academics are), you will likely find that sex with other smart people is much more satisfying than sex with the dumb.

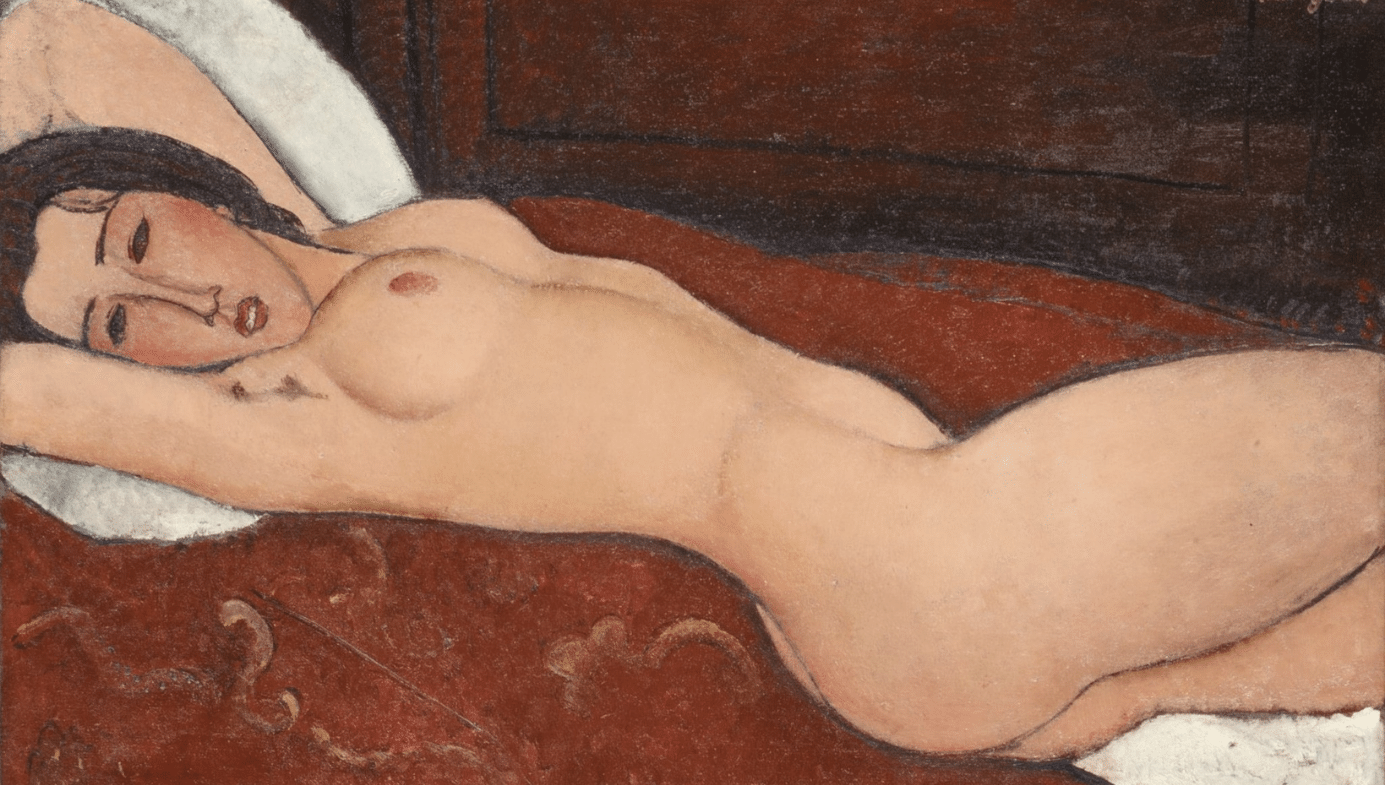

Somewhere between Women’s Studies turning into Gender Studies and the university lawyers turning into risk managers, we seem to have lost the clitoris. As an historian, I consider this a rare case of history surprising us. Asked in 1970 to predict the likely trajectory of academic feminism from that moment forward, I doubt many would have expected that we would arrive at a place so devoid (or even ashamed) of open appreciation of female anatomy and physiology, and at a milieu so lacking in female sexual agency and pleasure.

Yet academic feminism has largely been absorbed into Gender Studies, and now, anyone given to exuberant talk of feeling like a natural woman risks being maligned as at best a dinosaur—who still believes in sex?!—and at worst a TERF (a supposedly “trans-exclusionary radical feminist”). Nowadays, you can’t love your innate trinkets without oppressing someone with your damned uterine privilege.

Less surprising, I suppose, is that university risk managers would prefer that we all leave sex at home—out of the classroom, out of the lab, out of the break room, even out of the library, where it has been blossoming since at least Aristotle. Sixty years after the pill transformed women’s lives, sex on campus doesn’t lead to babies, it leads to lawyers in polyester suits.

Bleh. This is a sad and sorry development. For a start, sex can be pretty delightful, and if you are a smart person (as many—though by no means all—academics are), you will likely find that sex with other smart people is much more satisfying than sex with the dumb. Smart people are most likely to meet when they work together. Yet to broach the idea of sex with someone at work today? Mais non! Academic life to such a great extent still valorizes the mind at the prideful expense of bodily pleasure. But wouldn’t it be nice if we could really break from the monasteries from which our universities emerged and get laid sometimes without quite so much fear and shame and paperwork?

Then there are the kids to consider. Our fear of talking about sex—never mind teaching about it—has left the present generation of the young with no place to engage intellectually with the concept of eroticism. With so much monumentally bad sex ed (or near-total lack of sex ed) in our public schools, many of our undergraduates have been exposed to huge amounts of pornography but remarkably little information about their own bodies. We are willing to talk with them about gender, but not about the flesh that performs it.

But they aren’t going to learn how orgasms work—physically, culturally, and linguistically—by talking about gender. Nothing stops discussion of the orgasm like a discussion of gender. And while gender-based oppression strikes me as a very important thing for young people to learn about and understand—feminism made my good life possible—true emancipation requires the sexual liberation that comes from women really knowing their own sex.

I say this in part from personal experience. Like a lot of young women who grew up Roman Catholic, I found my clitoris in a book. The book was Our Bodies, Ourselves and the year was circa 1985. While I was also reading feminist texts about things like wage gaps, unequal social expectations of mothers versus fathers, and the justice system’s revictimization of rape survivors, reading sex-positive material by women about my anatomy and physiology was a critical component of being fully empowered. Sexual knowledge was and is sexual power.

When, circa 1998, I decided to teach a class on sex and gender to my high-achieving science undergraduates at the Lyman Briggs School of Michigan State University, I was unsurprised to discover that my students wanted to know at least as much about biological sex and human sexuality as they did about gender. For many of them, there was no other place but my Science Studies class where someone could answer their questions about eroticism.

As I was polishing up the syllabus for the first version of that class, the university sent us all a brochure about the latest sexual harassment policy. Reading it and deciding it was garbage—much more concerned with protecting the university’s administration than protecting women—I decided to annotate my syllabus to inform the Lyman Briggs School’s director of all the ways I intended to violate their policy. For example, I would be showing photos of genitals and discussing them with my undergraduate science students. We would have conversations that were likely to implicate our own sex lives, and I would let them write papers about their sex lives if they wanted; then, I would then shamelessly grade those papers. Finally, we would talk about sex during office hours.

To his credit, our director—a mathematician—thanked me for the warning and then began voluntarily reading from the humanities literature about the ways in which talking about sex is a form of sex. One cannot teach about sex without at some level engaging our sexual cultures as well as the parts of our brains that respond to sexual cues. (We rather elegantly ignored the implications for our conversation. Tea was sipped.) On the first day of class, I went over the brochure and the syllabus with the students and explained to them where we would be violating the university’s policy. I suggested they drop the class if they didn’t feel comfortable with the topics we were going to engage. The next day, rather than having anyone drop, I had a waiting list of 20 students. The need felt greater and greater all the time.

Nevertheless, I hear from colleagues all over the country that they have stripped their syllabi of all eroticism, chiefly out of fear of progressives hauling them before the Title IX tribunals on charges of insensitivity, victimization, and general wrong-thinking. Who could have guessed that in 2021, the chastity belts would be distributed not by the patriarchy, but by people earnestly bearing Rosie the Riveter t-shirts? No mention may be made of the fact that the sex-policing is often carried out by women my age who are happy to diffuse the sexual potential of younger women under the guise of sparing them harassment. What a genius move by some, to take these young women who might otherwise be in competition with us for resources and turn them into our prudish foot-soldiers, convinced all the while that we are protecting them.

Of course, to some extent we are. There are some truly dreadful jerks on every campus, people (typically, though not always, men) who will distribute certain resources and limit access to others chiefly on the basis of who is willing to stroke their egos and other things. Being sex-positive doesn’t mean having to pretend sexual harassment doesn't exist and isn't pernicious. And we know it disproportionately harms women. I had colleagues driven out of their professions by serial harassers who were only effectively outed after #MeToo, years too late.

Then there is the problem, if you are supportive of heterodoxy, of recognizing that sex-positivity is a value not embraced by a lot of conservatives. In our teaching and presentations, it can be difficult to think about how to engage the reality of human sex and sexuality without rattling people—including students and faculty—who think public sexual repression to be a virtue. While I don’t agree with their takes, as a sex-positive person I don’t want to be a killjoy to their lifestyle choices.

Cross-campus efforts are being made to stop sexual predators and end quid-pro-quos, to level the playing fields, to make all students and faculty feel welcome, and to respect and support people of all genders. All these initiatives make me feel as if we’re getting somewhere. But can we also acknowledge that sex will always be with us, and that this is a good thing? Can we know our bodies on campus without losing our minds?