Recommended

Mate Selection for Modernity

Hypergamy is an evolved sexual strategy where individuals mate with and/or marry those most capable of providing long term security. It is the act of marrying up.

“All things in nature occur mathematically.”

~ Rene Descartes

Dating and the process of mate selection have changed. The rise of hook-up culture, proliferation of dating apps, and ever-increasing age of first marriage are evidence of this. This current situation can be summarized along four parameters:

- Increasing female achievement.

- Growing variability in male status and competence.

- An evolutionary desire among females to marry up.

- The globalization of the sexual marketplace and resultant collapse of local status hierarchies.

Together, these conditions have created pronounced imbalances in the modern sexual marketplace. Put plainly, an increasing cohort of successful women are chasing a shrinking number of high-value, commitment-averse men.

At a cursory level, much of this can be explained by sex ratios and partner availability. However, the underlying structure of modern mate selection is fundamentally mathematical. For us to truly understand the causes and consequences of the modern sexual marketplace, a bit of math is required.

Chads, dads, and hypergamy

Hypergamy is an evolved sexual strategy where individuals mate with and/or marry those most capable of providing long term security. It is the act of marrying up. Though human males can and do engage in hypergamy, it is a concept and strategy most often attributed to females. It is an artefact born out of raw Darwinian necessity.

According to evolutionary psychologist David Buss, the dangers of our evolutionary past favoured females who were highly selective of their mates. To both survive childbirth and raise healthy offspring, early human females needed to evaluate a man’s current position as well as his potential and future trajectories. Consequentially, females typically mate above and across dominance hierarchies whereas males typically mate below and across them.

Hypergamy is often manifested though physical protection. It is thus understandable why physical characteristics like athleticism, strength, and height are prioritized by females. These are cues to solutions to the problem of protection.

Let us consider height. According to one study, women were most satisfied when their partner was 21cm taller. This is corroborated by other studies which found that 49 percent of women preferred dating taller men and that the shortest man a woman would date was 5 feet 9 inches. Moreover, a study of undergraduates reported that only four percent of women would accept a relationship where the woman was taller. In general, tall men are more likely to obtain attractive partners, less likely to remain childless, and have a greater number of children relative to short men.

However, height isn’t the only factor which determines access to the sexual marketplace. Financial prospects matter as well.

A 1939 study found that American women rated good financial prospects twice as highly as males when gauging the value of a marriage partner. This finding was replicated in studies conducted in 1956 and 1967. Moreover, David Buss, attempting to replicate these studies, surveyed 1,491 Americans across four states in the mid-1980s. Once again, women valued good financial prospects in a mate roughly twice as much as men did. This gender difference has not changed. In fact, a 2014 Pew Research survey reported that 78 percent of unmarried women placed a high premium on finding a spouse with a steady job. Only 48 percent of men shared this view.

In a study of the attributes valued in a marriage partner, psychologist Douglas Kenrick asked men and women to indicate the “minimum percentiles” of each attribute that they would find acceptable. When it came to earning capacity, women indicated that they preferred a man who earned more than 70 percent of all other men. In contrast, men desired a mate that earned more than 40 percent of all other women.

Furthermore, researchers from the University of Aberdeen found that males could move themselves two points higher on a bespoke attractiveness scale by increasing their salary tenfold. For females to achieve a similar two-point effect, their salary would need to increase by 10,000 times. The socioeconomic status of a man is a major determinant of his attractiveness to a woman, but the opposite is not true.

What happens when a woman out-earns her husband? One study found that marriages where the wife out-earned the husband were 50 percent more likely to end in divorce. This is corroborated by Finnish researchers who concluded that whereas “a husband’s high income decreased the risk of divorce … a wife’s high income increased the risk at all levels of the other spouse’s income, but especially when the wife’s income exceeded the husband’s.”

Furthermore, a study of Swedish couples reported that when the wife contributed 80 percent or more to the total income, the divorce risk was twice as high as when she contributed less than 20 percent. Curiously, one study also found that men who were not the primary breadwinner were more likely to use erectile dysfunction medication relative to men that were.

The notion that most women are callous resource extractors is inaccurate. They are not necessarily after resources, but rather the primary predictors of resource acquisition. Namely, intelligence and hard work.

To this extent, researchers, analysing 120 personal dating ads, found that education was one of the two strongest predictors of how many responses a man received from women. The other was income. Moreover, researchers in Australia reported that women were more likely to initiate contact with a man if his education exceeded hers. Indeed, researchers from Ghent University also reported that women on Tinder were 91 percent more likely to “like” the profile of a man with a master’s degree compared to a man with a bachelor’s degree. The cliché that women prefer to marry doctors, lawyers, and entrepreneurs is not a pithy truism. It is a derivative of hypergamy.

While hypergamy is traditionally defined along the lines of security and provisioning, it is important to stipulate that there is a secondary component that deals with raw, unfettered sex appeal. It isn’t just about dollar signs and IQ points. Ask Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

Hypergamy is, to an extent, favourable to the stereotypical Chad. Regardless of his college GPA or credit score, the bad boy who embodies dark triad personality traits is beloved. As such, hypergamy in its truest form prioritizes a Rebis-like amalgam of the beta and the alpha. What women truly desire then is the Chad who can ultimately fulfil his role as the dad.

Hypergamy is an evolutionary fixture. Hating it is tantamount to hating thermodynamic laws or Archimedean axioms. It simply is. Moreover, it is hypergamy that created the competence hierarchies that are used to structure human societies. If seeking to reproduce with choosy females galvanizes a man into conquest and self-actualization, are we not better for it? But what is the effect of hypergamy when females outperform males?

It’s lonely at the top

Compared to their male counterparts, young women have the upper hand in education and earning power.

Since the 1990s, women have outnumbered men in both college enrolment and college completion rates, reversing a trend that lasted through the 1960s and ’70s. In 1960, there were 1.6 males for every female who graduated from a four-year US college. Compare this to 2003 where there were 1.35 females for every male college graduate. By 2013, 37 percent of women aged 25 to 29 had at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 30 percent of men in the same age range. Moreover, 12 percent of women in this age group had a post-graduate or professional degree compared to eight percent of men.

But it’s not just the US; the UK, Panama, Sri Lanka, Argentina, Cuba, Jamaica and Brunei have some of the highest female to male ratios in higher education.

Young women are also out-earning young men. According to data compiled by the Press Association, women between the ages of 22 and 29 typically earned £1,111 more each year compared to males in the same age group. As it stands, women contribute $7 trillion to the US gross domestic product per year and are the primary breadwinner in 40 percent of US households.

Crucially, the more professionally successful a woman is, the stronger her preference for successful men.

In a study of financially successful newlywed women, researchers concluded that “successful women place an even greater value than less successful women on mates who have professional degrees, high social status, and greater intelligence.” This trend is also present in cross-cultural contexts. Separate studies of 1,670 Spanish, 288 Jordanian, 127 Serbian, and 1,851 English women all found that high resource women desired mates with greater status and more resources. In general, single women are three times as likely as men to say that they wouldn’t consider a relationship with someone making less than them.

When paired with the ground truth of hypergamy, the growth of female attainment (and comparative stagnation of male attainment) amounts to a law of diminishing returns. The more a woman achieves, the less suitable mates she has to choose from. It is, indeed, difficult to marry above and across dominance hierarchies if you sit atop your own. This difficulty is further compounded by the fact that older high-powered women must compete not only among themselves but with younger women for a fleeting number of high-value men.

Make no mistake, men’s evolved criteria for mate selection prioritize youth and appearance. As men age, they desire women who are increasingly younger than they are. As such, men are less interested in the professional success of prospective partners. This dynamic is borne out in the data.

Studies using data from classic online dating websites and speed-dating both found that men exhibited less of a preference for women whose intelligence or ambition exceeded their own. A study by four UK universities found that a woman’s likelihood of marriage decreased by 40 percent for each 16-point increase in her IQ. In contrast, men experienced a 35 percent increase in the likelihood of marriage for each 16-point IQ increase. Finally, researchers reported that men displayed lower levels of implicit self-esteem when confronted with their female partner’s success. The opposite holds true for women when their male partner succeeded.

Interestingly, some women have wised up to this dynamic. In a 2017 study of elite MBA students, three researchers found that single and non-single women provided similar answers to questions regarding salary and leadership aspirations when they thought their responses would remain anonymous. However, single women displayed less ambitious aspirations when they believed classmates would see their answers. The researchers concluded that highly educated women may avoid signalling professional ambition because it could be penalized in the marriage market.

Successful women face a shortage of demographically superior men to marry. Indeed, the nascent decline in marriage has been attributed to a putative shortage of economically attractive partners for unmarried women. Applying data imputation methods to national survey data, researchers found that unmarried women face an overall shortage of partners with either a bachelor’s degree or yearly income exceeding $40,000.

This asymmetry in the sexual marketplace has been well documented in Jon Birger’s book Date-onomics as well as an article penned by myself and Rob Henderson.

Premised on sex ratios, a surplus of women in education and economic groups caters to men’s desire for multiple partners. The relative rarity of men within these groups means that women, in competition with other females, are more likely to conform to the sexual strategy of males. In these environments, hookup culture is more prevalent. In contrast, environments in which men are numerous see more long-term relationships.

While this observation is far from novel, what is not well understood is the extent to which this imbalance is likely to worsen.

In 2012, there were 88 employed college-educated young men for every 100 college-educated never-married young women. Among never-married young adults with a post-graduate degree, there were only 77 men for every 100 women. In addition, the ratio of employed men to young never-married women has consistently declined. In 1960, there were 139 employed men for every 100 young never-married women. As of 2012, this ratio sits at 91 employed men for every 100 young never-married women.

If you think these ratios are troubling wait till you see what they look like in 20 years. Fortunately, you don’t have to wait that long.

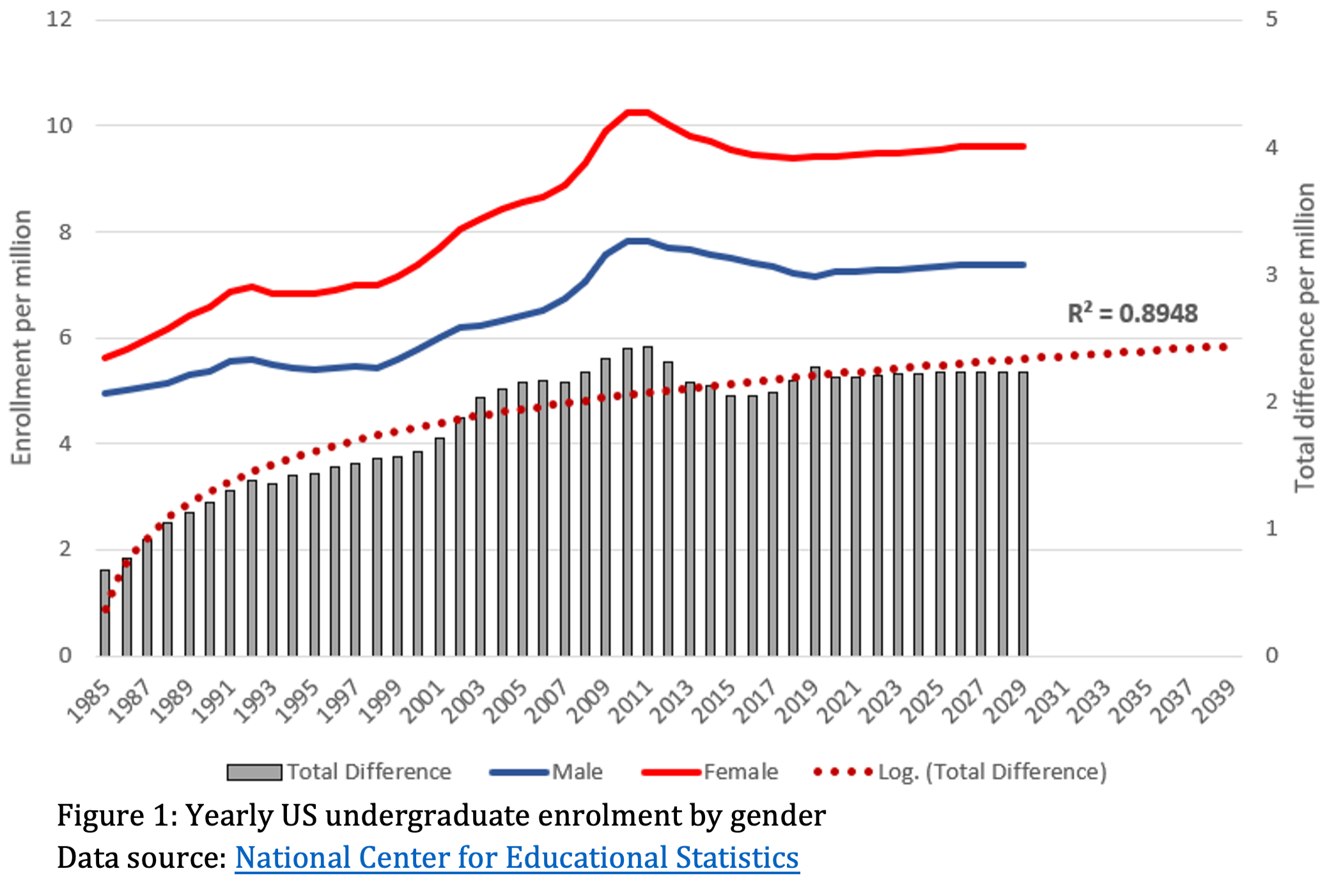

Figure 1 displays yearly college enrollment among males and females in the US. Here, I use logarithmic forecasting to show the estimated total difference in the enrollment per million between the sexes by 2039. Notably, a high R2 of 0.8948 tells us that the model is very accurate.

Since 1985, the undergraduate enrolment gap has grown in favour of women. Indeed, the logarithmic trendline remains fairly stable, with slight year-on-year increases in the total difference per million. There is an average yearly surplus of 2.2 million female undergrad enrolees between 2020 and 2029. Between 2030 and 2039, this number increases to 2.3 million. Cumulatively, there will be a whopping 45.1 million women without an equally educated male partner between 2020 and 2039. This colossal imbalance bleeds over into the job market as well.

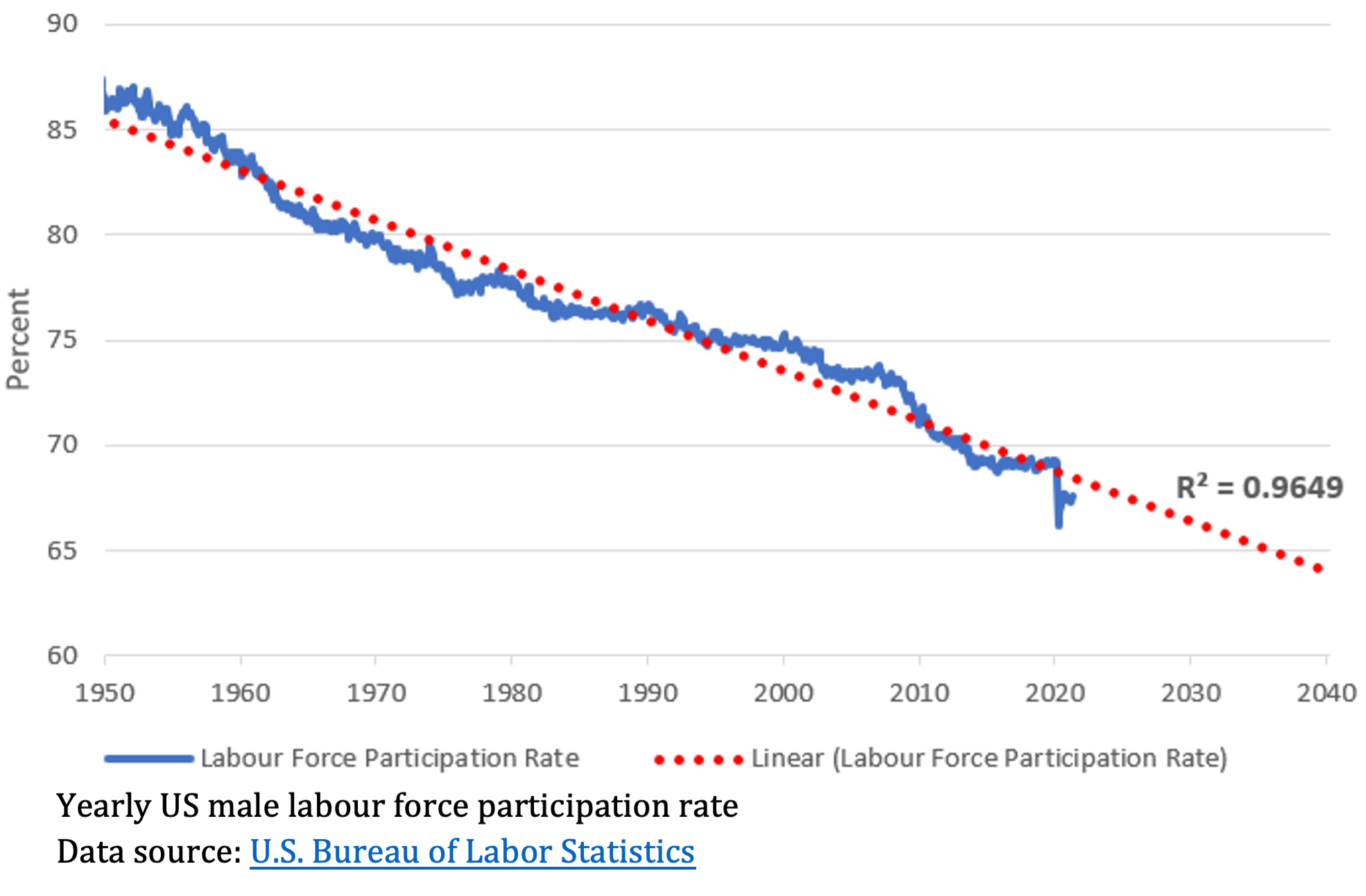

Figure 2 displays the yearly labour force participation rate among US males. Here, linear forecasting is used to show the estimated labour force participation rate in the years between 2021 and 2040. Again, the model is very accurate with an R2 of 0.9649.

Based on these numbers, the male labour force participation rate exhibits a slow but gradual decline, falling from a high of 87 percent in 1950 to a low of 68 percent in 2019. Excluding the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown, male labour force participation has fallen by 0.1 percent each month since 1950. Moreover, there has been a 5.4 percent drop since 2005. Based on the linear trendline, the male labour force participation rate will continue to decline, falling below 65 percent for the first time by 2040. These particular numbers prove ominous for educated women as research from the US and Sweden indicate that educated women are more likely to marry a less-educated partner if he makes more than her.

Together, these figures point to a lonely future for many educated, career-oriented young women. While some might be understandably sceptical of my findings and conclusions, they are corroborated by a 35-page report put out by Morgan Stanley in 2019.

Cleverly titled the Rise of the SHEconomy, Morgan Stanley forecasts that 45 percent of working women between the ages of 25 and 44 will be single and childless by 2030, the largest share in history. Single women are expected to grow by 1.2 percent annually from 2018–2030 compared with an 0.8 percent growth for the overall US population. By 2030, the percentage of single women will outpace that of married women.

While some of these women may very well eschew the tenets of hypergamy and settle for a man below their financial and educational station, many will seek out a high-value partner. This is where things truly become onerous.

Power! Unlimited power!

In selecting a long-term partner, let’s suppose that single women in the US over the age of 18 based their selection criteria on the “rule of sixes.” This is a dating heuristic which stipulates that a woman’s ideal partner must have 1) a six-figure income, 2) six-pack abs, and 3) is six-feet tall.

There are, of course, many qualities and characteristics beyond these three which make a man attractive. However, for the purposes of this mathematical object lesson, I’ve selected the rule of sixes as it represents a simple proxy for hypergamic mate selection. Let’s run the numbers.

Of all men in the US, it is estimated that 13 percent have a yearly income of $100,000 or more, 14.5 percent are six feet or taller, and 10 percent have six-pack abs. Though the number is likely to be far lower, let’s suppose that one percent of American men possessed all three qualities. This equates to 1.009 million men aged 18 or older. In comparison, there are an estimated 33.8 million never-married women aged 18 or older in the US.

If we keep within the parameters of this model, this group of women effectively outnumber their desired partners by a factor of 34. Moreover, if each man is paired with a single woman, this leaves 32.8 million women without a mate. This is a staggering imbalance.

Referred to as the 80/20 rule or Pareto principle, a power law distribution describes a relationship between two variables where a small amount of variable A accounts for an outsized proportion of variable B.

The modern sexual marketplace is predicated on a power law where a small number of highly successful men are desired by the majority of women. While this distribution is unlikely to be perfectly 80/20, an imbalance of some sort is likely. Importantly, I’m not suggesting that a small cadre of men date and sleep with the majority of women. That’s a logistical impossibility. However, there is an asymmetry when it comes to attraction and attention. This is evident from research on Tinder.

According to a study of the dating app, whereas men “liked” 60 percent of female profiles they viewed, women liked only 4.5 percent of male profiles. Moreover, women, on average, viewed 80 percent of men on dating apps as below average in attractiveness. Importantly, one study, seeking to quantify the prospects of success on Tinder, determined that “the bottom 80 percent of men (in terms of attractiveness) are competing for the bottom 22 percent of women and the top 78 percent of women are competing for the top 20 percent of men”.

While power law distributions occur naturally in a multitude of settings, it is my contention that its presence on Tinder is by design. The app’s core algorithm is not calibrated to produce equal outcomes. This is a function of its use of the ELO rating system.

Created by the Hungarian-American physicist Arpad Elo, the ELO rating system was designed to rank chess players in national tournaments. Put simply, a player’s ranking is generated from the ratings of their opponents and the results scored against them.

While Tinder’s algorithm is assuredly complex, it is fundamentally a “vast voting system” premised on ELO. To elaborate, the “desirability” of a Tinder profile is premised on how many users have “liked” it and what the desirability of these profiles were.

The more likes you accrue, the greater your desirability. Furthermore, your overall desirability shoots up when a user with a higher desirability likes your profile. If a profile with an equal or lower desirability does not like yours, your rating will take a hit. Of course, the algorithm will serve you profiles whose desirability rating is similar to your own. This ranking system is tailor-made for a power law distribution.

Theoretically, an average-looking male will not be able to increase his desirability rating if higher-rated women do not like his profile. And why would they? Regardless of their desirability rating, women using Tinder aren’t there for Joey Bag o’Donuts. They’re there for Chad or some high-value equivalent. Indeed, research indicates that men are more than twice as likely to receive a reply from women less desirable than themselves than from more desirable ones.

Recall that women on Tinder only liked 4.5 percent of male profiles while men liked 60 percent of female profiles. Furthermore, keep in mind that Tinder’s userbase is 72 percent male and 28 percent female. This means that 72 percent of the userbase is liking 60 percent of the other 28 percent while the 28 percent is only liking 4.5 percent of the other 72 percent. As such, the desirability rating of most women on the app is inflated due to excess likes from males with lower, equal, or higher ratings.

This inflation places women with an objectively lower desirability rating in the same pool with highly desirable men that have been naturally selected. As such, a small number of men receive a large portion of attention and interest from most women on Tinder.

In recent years, Tinder has maintained that it has pivoted away from ELO. However, this is hard to believe. While subtle changes may have been made to the algorithm, it is likely that the core mechanics remain intact.

Tinder’s financial metagame is contingent on the facilitation of a power law distribution among its users. Given that the top 78 percent of women on the app are vying for the top 20 percent of men, Tinder will do everything it can to keep these men swiping. It cares little for the bottom 80 and 22 percent of men and women as these users do not generate much traffic.

This power law imbalance in the sexual marketplace is one possible explanation for the increase in male sexlessness. According to the General Social Survey, the share of men younger than 30 reporting no sex has nearly tripled from eight percent in 2008 to 28 percent in 2018.

Do you even math, bro?

Over the past few months, I’ve attempted to create a mathematical model to describe this imbalance in the sexual marketplace. Mathematical modelling is a useful investigative tool for understanding human behaviour.

Though I designed several linear, polynomial, and threshold models, none were able to adequately capture how men and women selected their mates. Fortunately, I came across a 2016 paper by evolutionary psychologists Daniel Conroy-Beam and David Buss which proposed the use of a Euclidian integration algorithm to determine how mate preference and selection were linked.

The problem with my earlier models was that they treated mate preferences in isolation. Potential mates do not present themselves one trait at a time. Rather, we evaluate potential mates based on a bevy of traits.

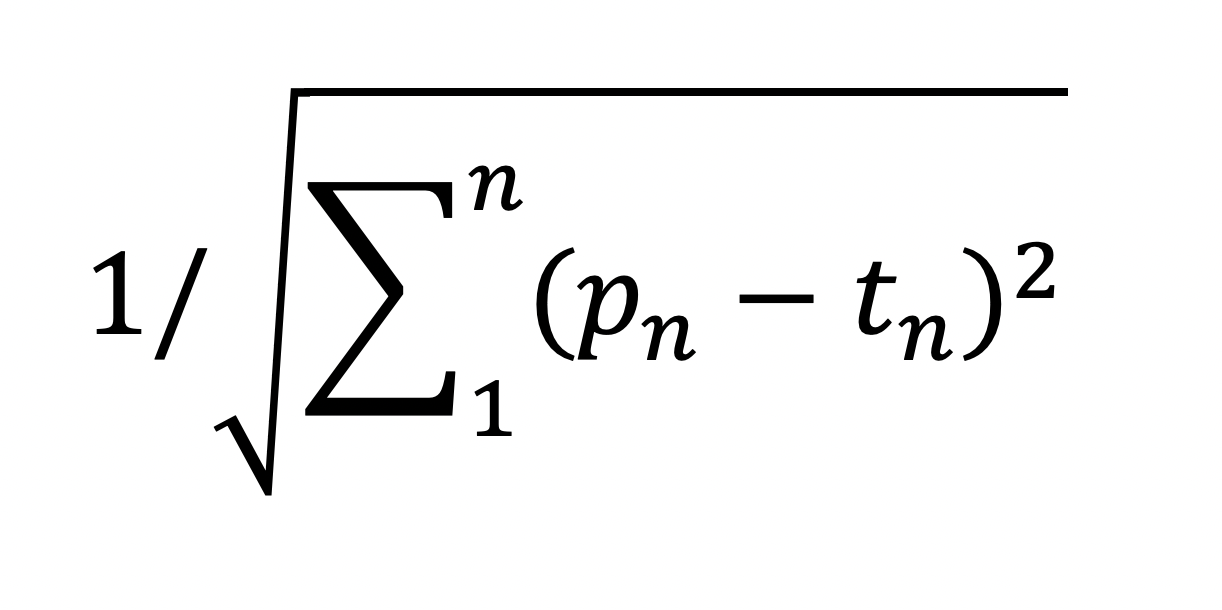

A Euclidian integration algorithm incorporates mate preferences while capturing the full array of potential mates and their traits. Attraction to a mate is computed as the inverse distance between a person’s preference and each potential mate’s corresponding traits. In plain English, the model compares what you’re looking for in a mate with whether prospective mates possess these traits. The closer these two things are, the more a mate matches your preferences. Conroy-Beam and Buss’s mathematical model was as such:

where n = the number of traits, p = a person’s preference value, and t = a mate’s trait value.

This mathematical model offers key insight into our unbalanced sexual marketplace. The number and weight of a woman’s mate preferences is negatively correlated with the number of eligible mates that are available to her. Thus, the distance of a prospective mate to a woman increases with each new preference she adds. Put simply, the more you demand, the less you receive.

More generally, there’s a disconnect between what women want and what is actually available to them. Whereas greater male attainment increases the number of romantic options a man has, greater female attainment reduces the number of options a woman has.

This imbalance in the sexual marketplace is not a good thing. A society teeming with lonely women and sexually frustrated men is one hurtling toward disaster. It is imperative that we, as a society, think carefully about solutions to this burgeoning crisis.