Psychology

Persuasion and the Prestige Paradox: Are High Status People More Likely to Lie?

The first type, termed the “central” route, comes from careful and thoughtful consideration of the messages we hear.

Many have discovered an argument hack. They don’t need to argue that something is false. They just need to show that it’s associated with low status. The converse is also true: You don’t need to argue that something is true. You just need to show that it’s associated with high status. And when low status people express the truth, it sometimes becomes high status to lie.

In the 1980s, the psychologists Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo developed the “Elaboration Likelihood Model” to describe how persuasion works. “Elaboration” here means the extent to which a person carefully thinks about the information. When people’s motivation and ability to engage in careful thinking is present, the “elaboration likelihood” is high. This means people are likely to pay attention to the relevant information and draw conclusions based on the merits of the arguments or the message. When elaboration likelihood is high, a person is willing to expend their cognitive resources to update their views.

Two paths to persuasion

The idea is that there are two paths, or two “routes,” to persuading others. The first type, termed the “central” route, comes from careful and thoughtful consideration of the messages we hear. When the central route is engaged, we actively evaluate the information presented, and try to discern whether or not it’s true.

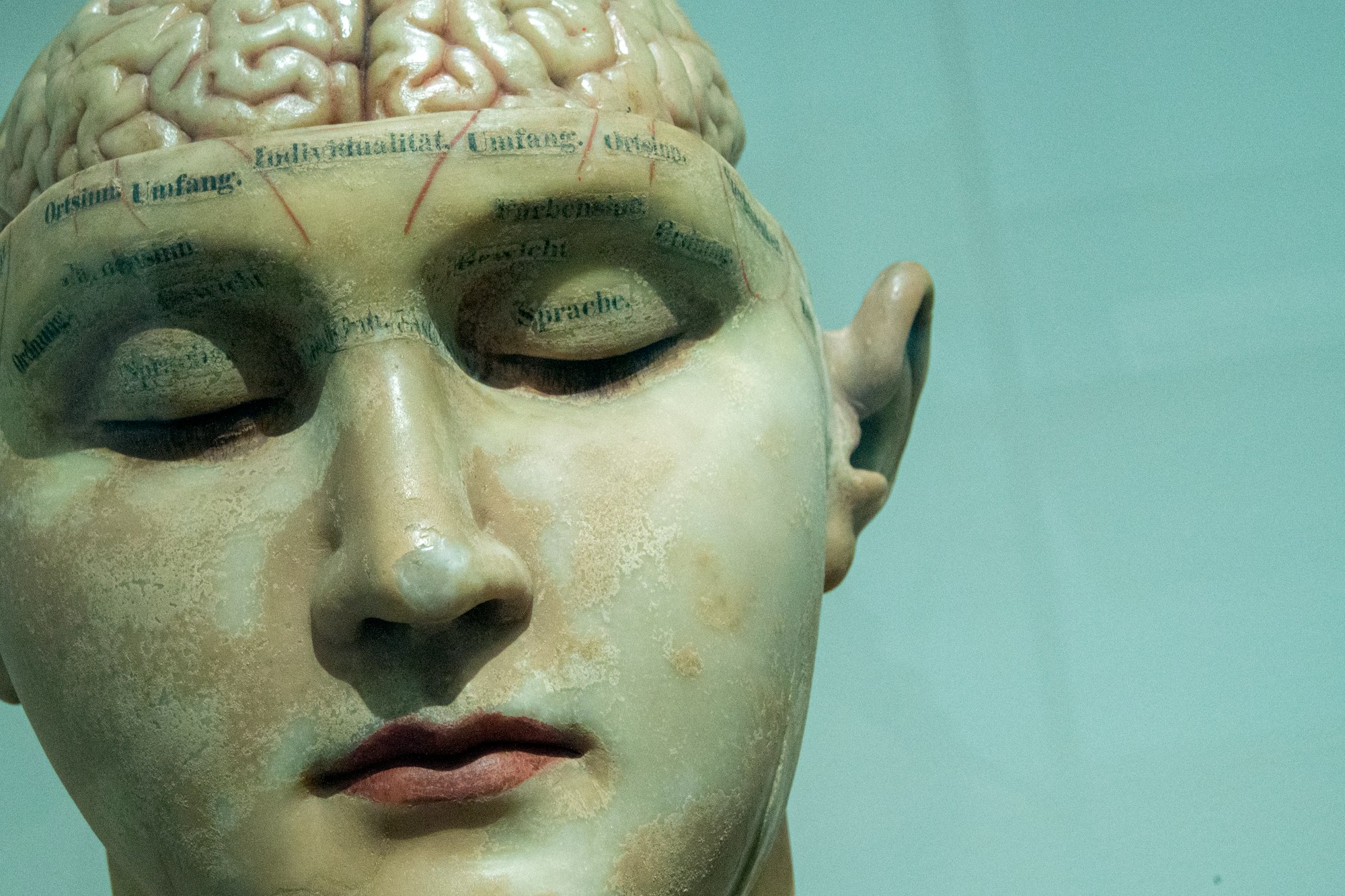

When the “peripheral” route is engaged, we pay more attention to cues apart from the actual information or content or the message. For example, we might evaluate someone’s argument based on how attractive they are or where they were educated, without considering the actual merits of their message.

When we accept a message through the peripheral route, we tend to be more passive than when we accept a message through the central route. Unfortunately, the peripheral route is more prevalent because we are exposed to an increasingly large amount of information.

The renowned psychologists Susan Fiske and Shelley Taylor have characterized humans as “cognitive misers.” They write, “People are limited in their capacity to process information, so they take shortcuts whenever they can.”

We are lazy creatures who try to expend as little mental energy as possible.

And people are typically less motivated to scrutinize a message if the source is considered to be an expert. We interpret the message through the peripheral route.

This is one reason why media outlets often appoint experts who mirror their political values. These experts lend credibility to the views the outlet espouses. Interestingly, though, expertise appears to influence persuasion only if the individual is identified as an expert before they communicate their message. Research has found that when a person is told the source is an expert after listening to the message, this new information does not increase the person’s likelihood of believing the message.

It works the other way, too. If a person is told that a source is not an expert before the message, the person tends to be more skeptical of the message. If told the source is not an expert after the message, this has no effect on a person’s likelihood of believing the message.

This suggests that knowing a source is an expert reduces our motivation to engage in central processing. We let our guards down.

As motivation and/or ability to process arguments is decreased, peripheral cues become more important for persuasion. Which might not bode well.

However, when we update our beliefs by weighing the actual merits of an argument (central route), our updated beliefs tend to endure and are more robust against counterpersuasion, compared to when we update our beliefs through peripheral processing. If we come to believe something through careful and thoughtful consideration, that belief is more resilient to change.

This means we can be more easily manipulated through the peripheral route. If we are convinced of something via the peripheral route, a manipulator will be more successful at using the peripheral route once again to alter our initial belief.

Social consequences of our beliefs

But why does this matter? Because by understanding how and why we come to hold our beliefs, we can better understand ourselves and guard against manipulation.

The founders of the elaboration likelihood model wrote that, “Ultimately, we suspect that attitudes are seen as correct or proper to the extent that they are viewed as beneficial for the physical or psychological well-being of the person.”

In his book The Social Leap, the evolutionary psychologist William von Hippel writes, “a substantial reason we evolved such large brains is to navigate our social world… A great deal of the value that exists in the social world is created by consensus rather than discovered in an objective sense… our cognitive machinery evolved to be only partially constrained by objective reality.” Our social brains process information not only by examining the facts, but also considering the social consequences of what happens to our reputations if we believe something.

Indeed, in his influential theory of social comparison processes, the eminent psychologist Leon Festinger suggested that people evaluate the “correctness” of their opinions by comparing them to the opinions of others. When we see others hold the same beliefs as us, our own confidence in those beliefs increases. Which is one reason why people are more likely to proselytize beliefs that cannot be verified through empirical means.

In short, people have a mechanism in their minds. It stops them from saying something that could lower their status, even if it’s true. And it propels them to say something that could increase their status, even if it’s false. Sometimes, local norms can push against this tendency. Certain communities (e.g., scientists) can obtain status among their peers for expressing truths. But if the norm is relaxed, people might default to seeking status over truth if status confers the greater reward.

Furthermore, knowing that we could lose status if we don’t believe in something causes us to be more likely to believe in it to guard against that loss. Considerations of what happens to our own reputation guides our beliefs, leading us to adopt a popular view to preserve or enhance our social positions. We implicitly ask ourselves, “What are the social consequences of holding (or not holding) this belief?”

But our reputation isn’t the only thing that matters when considering what to believe. Equally important is the reputation of others. Returning to the peripheral route of persuasion, we decide whether to believe something not only if lots of people believe it, but also if the proponent of the belief is a prestigious person. If lots of people believe something, our likelihood of believing it increases. And if a high-status person believes something, we are more prone to believing it, too.

Prestigious role models

This starts when we are children. In her recent book Cognitive Gadgets, the Oxford psychologist Cecilia Hayes writes, “children show prestige bias; they are more likely to copy a model that adults regard as being higher social status- for example, their head-teacher rather than an equally familiar person of the same age and gender.” Hayes cites a 2013 study by Nicola McGuigan who found that five-year-old children are “selective copiers.” Results showed that kids were more likely to imitate their head-teacher rather than an equally familiar person of the same age and gender. Young children are more likely to imitate a person that adults regard as being higher status.

People in general favor mimicking prestigious people compared to ordinary people. This is why elites have an outsized effect on culture, and why it is important to scrutinize their ideas and opinions. As a descriptive observation, the opinions of my friend who works at McDonald’s have less effect on society than the opinions of my friend who works at McKinsey. If you have any kind of prominence, you unavoidably become a model that others, including children, are more likely to emulate.

Indeed, the Canadian anthropologist Jerome Barkow posits that people across the world view media figures as more prestigious than respected members of their local communities. People on screen appear to be attractive, wealthy, popular, and powerful. Barkow writes, “All over the world, children are learning not from members of their own community but from media figures whom they perceive as prestigious… local prestige is debased.” As this phenomenon continues to grow, the opinions and actions of the globally-prestigious carry even more influence.

Of course, people don’t copy others with high-status solely because they hope that mimicking them will boost their own status. We tend to believe that prestigious people are more competent; prominence is a heuristic for skill.

In a recent paper about prestige-based social learning, researchers Ángel V. Jiménez and Alex Mesoudi wrote that assessing competence directly “may be noisy and costly. Instead, social learners can use short-cuts either by making inferences from the appearance, personality, material possessions, etc. of the models.”

For instance, a military friend of mine used to be a tutor for rich high school students. He himself is not as wealthy as them, and disclosed to me that he paid $200 to replace his old earphones for AirPods. This was so that the kids and their families would believe he is in the same social position as them, and therefore qualified to teach.

Prestige paradox

Which brings us to a question: Who is most susceptible to manipulation via peripheral persuasion? It might seem intuitive to believe that people with less education are more manipulable. But research suggests this may not be true.

High-status people are more preoccupied with how others view them. Which means that educated and/or affluent people may be especially prone to peripheral, as opposed to central, methods of persuasion.

Indeed, the psychology professor Keith Stanovich, discussing his research on “myside bias,” has written, “if you are a person of high intelligence… you will be less likely than the average person to realize you have derived your beliefs from the social groups you belong to and because they fit with your temperament and your innate psychological propensities.”

Students and graduates of top universities are more prone to myside bias. They are more likely to “evaluate evidence, generate evidence, and test hypotheses in a manner biased toward their own prior beliefs, opinions, and attitudes.”

This is not unique to our own time. William Shirer, the American journalist and author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, described his experiences as a war correspondent in Nazi Germany. Shirer wrote, “Often in a German home or office or sometimes in a casual conversation with a stranger in a restaurant, beer hall, or café, I would meet with outlandish assertions from seemingly educated and intelligent persons. It was obvious they were parroting nonsense they heard on the radio or read in the newspapers. Sometimes one was tempted to say as much, but one was met with such incredulity, as if one had blasphemed the Almighty.”

Likewise, in a fascinating study on the collapse of the Soviet Union, researchers have found that university-educated people were two to three times more likely than high school graduates to say they supported the Communist Party. White-collar professional workers were likewise two to three times more supportive of communist ideology, relative to farm laborers and semi-skilled workers.

Patterns within the US today are consistent with these historical patterns. The Democratic political analyst David Shor has observed that, “Highly educated people tend to have more ideologically coherent and extreme views than working-class ones. We see this in issue polling and ideological self-identification. College-educated voters are way less likely to identify as moderate.”

One possibility for this is that regardless of time or place, affluent members of society are more likely to say the right things to either preserve status or gain more of it. A series of studies by researchers at the University of Queensland found that, “relative to lower-class individuals, upper-class individuals have a greater desire for wealth and status… it is those who have more to start with (i.e., upper-class individuals) who also strive to acquire more wealth and status.”

A more recent set of studies led by Cameron Anderson at the University of Berkeley found that social class, measured in terms of education and income, was positively associated with the desire for social status. People who had more education and money were more likely to agree with statements like “I enjoy having influence over other people’s decision making” and “It would please me to have a position of prestige and social standing.”

Social status loss aversion

Who feels most in danger of losing their reputations, though? Turns out, those same exact people. A survey by the Cato Institute in collaboration with YouGov asked a nationally representative sample of 2,000 Americans various questions about self-censorship.

They found that highly educated people are the most concerned about losing their jobs or missing out on job opportunities because of their political views. Twenty-five percent of those with a high school education or less are afraid of getting fired or hurting their employment prospects because of their political views, compared with 34 percent of college graduates and an astounding 44 percent of people with a postgraduate degree.

Results from a recent paper titled ‘Keeping Your Mouth Shut: Spiraling Self-Censorship in the United States’ by the political scientists James L. Gibson and Joseph L. Sutherland is consistent with the findings from Cato/Yougov. They find that self-censorship has skyrocketed. In the 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism, 13.4 percent of Americans reported that “felt less free to speak their mind than they used to.” In 1987, the figure had reached 20 percent. By 2019, 40 percent of Americans reported that they did not feel free to speak their minds. This isn’t a partisan issue, either. Gibson and Sutherland report that, “The percentage of Democrats who are worried about speaking their mind is just about identical to the percentage of Republicans who self-censor: 39 and 40 percent, respectively.”

The increase is especially pronounced among the educated class. The researchers report, “It is also noteworthy and perhaps unexpected that those who engage in self-censorship are not those with limited political resources… self-censorship is most common among those with the highest levels of education… This finding suggests a social learning process, with those with more education being more cognizant of social norms that discourage the expression of one’s views.”

Highly-educated people appear to be the most likely to express things they don’t necessarily believe for fear of losing their jobs or their reputation. Within the upper class, the true believers set the pace, and those who are loss-averse about their social positions go along with it.

Interestingly, there is suggestive evidence indicating that education is negatively associated with one’s sense of power. That is, the more education someone has, the more likely they are to agree with statements like, “Even if I voice them, my views have little sway” and “My ideas and opinions are often ignored.” Granted, the correlation is quite small (r = -.15). Still, the finding is significant and in the opposite direction of what most people would expect.

Research by Caitlin Drummond and Baruch Fischhoff at Carnegie Mellon University found that people with more education, science education, and science literacy are more polarized in their views about scientific issues depending on their political identity. For example, the people who are most concerned about climate change? College-educated Democrats. The people who are least concerned? College-educated Republicans. In contrast, less educated Democrats and Republicans are not so different from one another in their views about climate change.

Likewise, in an article titled “Academic and Political Elitism,” the sociologist Musa Al-Gharbi has summarized related research, writing, “compared to the general public, cognitively sophisticated voters are much more likely to form their positions on issues based on partisan cues of what they are ‘supposed’ to think in virtue of their identity as Democrats, Republicans, etc.”

High education and low opinions

It’s also useful to understand how highly educated people view others and their social relationships. Consider a paper titled ‘Seeing the Best or Worst in Others: A Measure of Generalized Other-Perceptions’ led by Richard Rau at the University of Münster. Rau and his colleagues were interested in how various factors influence people’s perceptions of others.

In the study, participants looked at social network profiles of people they did not know. They also viewed short video sequences of unfamiliar people describing a neutral personal experience like traveling to work. Researchers then asked participants to evaluate the people in the social media profiles and videos. Participants were asked how much they agreed with statements like “I like this person,” and “This person is cold-hearted.” Then participants responded to various demographic and personality questions about themselves.

Some findings weren’t so surprising. The researchers found, for example, that people who scored highly on the personality traits of openness and agreeableness tended to hold more favorable views of others.

More sobering, though, is that higher education was consistently related to less positive views of other people. In their paper they write, “to understand people’s feelings, behaviors, and social relationships, it is of key importance to know which general view they hold about others… the better people are educated, the less positive their other-perceptions are.”

So affluent people care the most about status, believe they have little power, are afraid of losing their jobs and reputation, and have less favorable views of others.

In short, opinions can confer status regardless of their truth value. And the individuals most likely to express certain opinions in order to preserve or enhance their status are also those who are already on the upper rungs of the social ladder.

There may be unpleasant consequences for this misguided use of intellect and time on the part of highly educated and affluent people. If the most fortunate members of society spend more time speaking in hushed tones, or live in fear of expressing themselves, or are more involved in culture wars, that is less time they could spend using their mental and economic resources to solve serious problems.

Aliens and our monkey brain

There’s an idea named after the Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi, called the Fermi Paradox. In short, it describes the apparent contradiction between the fact that the universe is nearly 14 billion years old, there are billions of stars and planets, and intelligent life on Earth evolved relatively quickly. This suggests that there are many other Earth-like planets out there that have also evolved intelligent life. So why haven’t we encountered any?

The psychology professor Geoffrey Miller suggested that as intelligent species become technologically advanced, they spend more time entertaining themselves than on interstellar space travel. Rather than actually going to Mars, they spend more time pretending to go to Mars via movies and video games and VR.

Perhaps, though, such technology enables us to get involved in something equally exciting: Tribal warfare. Dunking on social media tells our monkey brain that we are rising in prominence, even though by next week people will have forgotten and moved on to the next round of gossip. Advanced tech exploits the brains of ideologues, who then create a culture where others spend too much time pledging fealty to ideologies rather than developing new ideas and technology for the benefit of humankind.