Culture Wars

Visions Are Sublime; Social Reform Is Messy

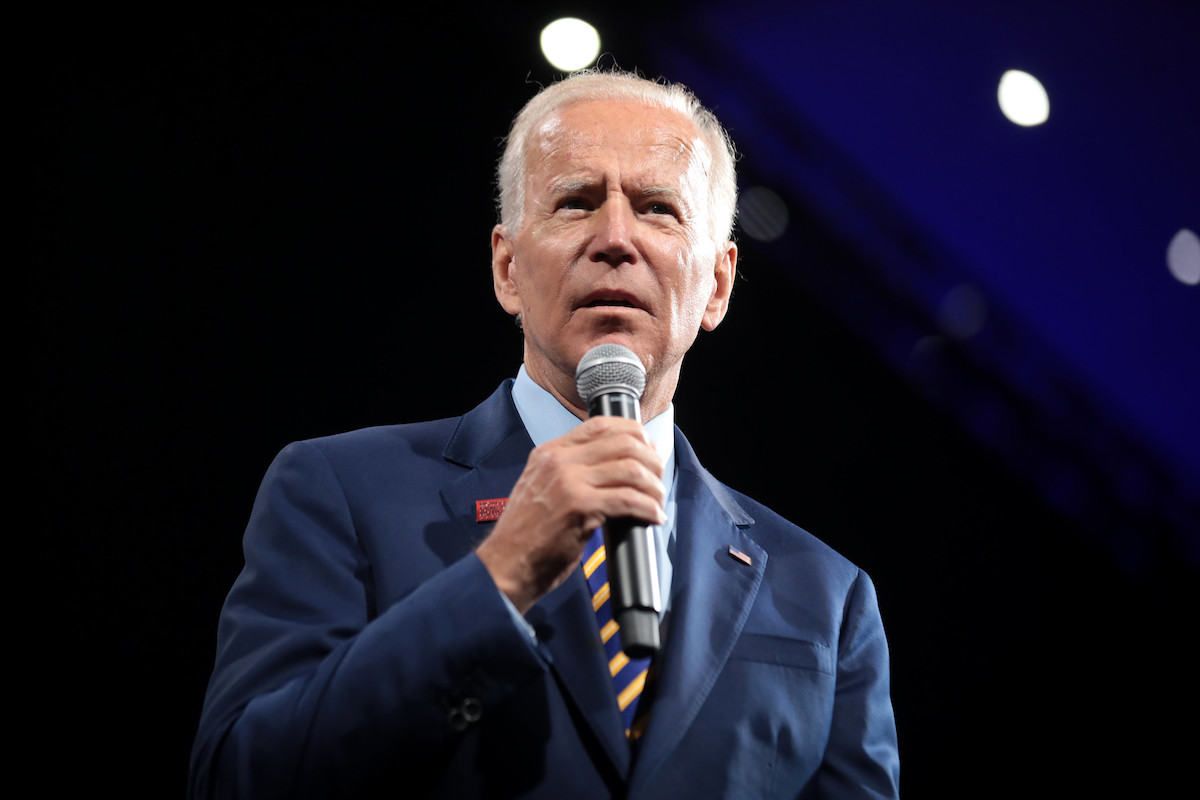

The Democratic party’s radical wing, which mostly set aside its many differences with Biden during his contest with Trump, wants a more rapid pace of change than the 78-year old centrist would wish.

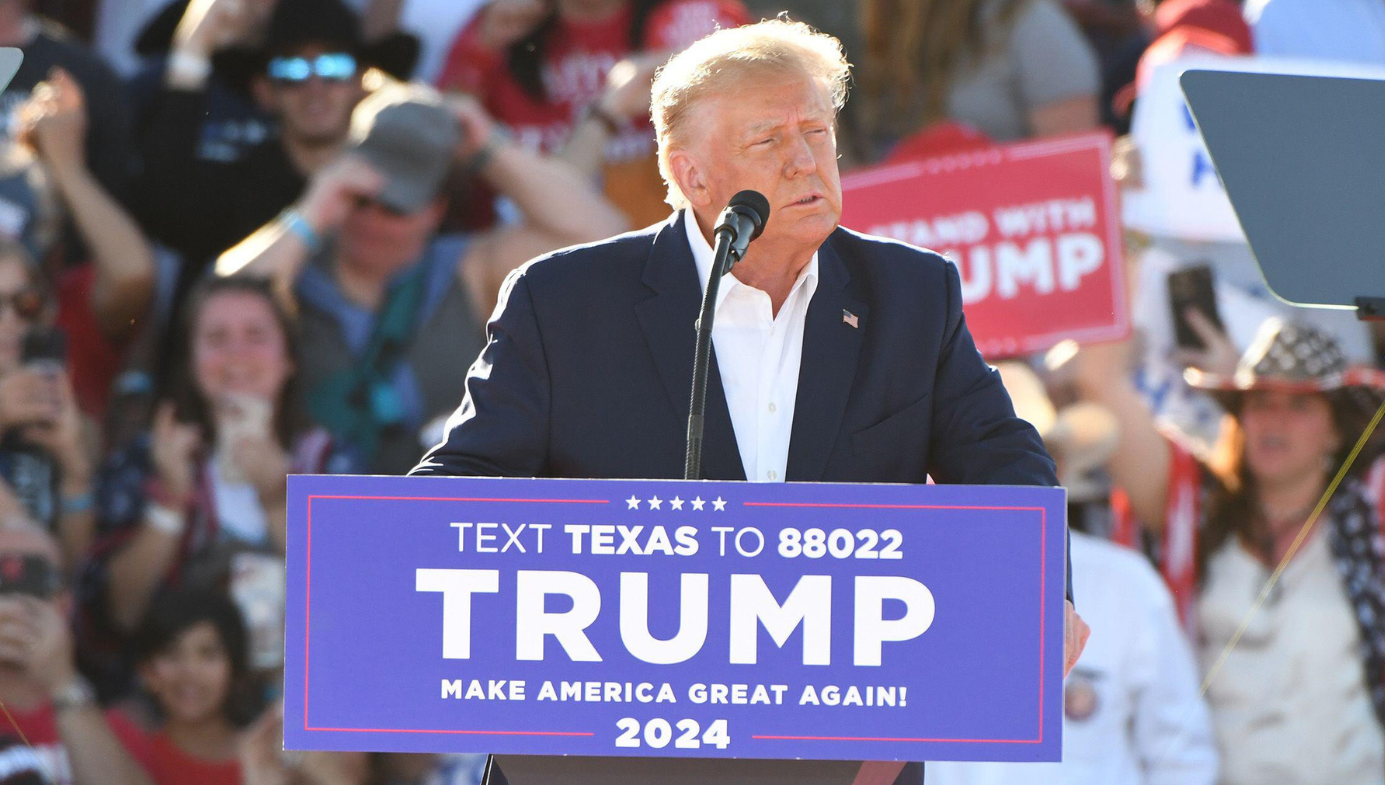

The 2020 US elections and the subsequent inauguration of Joe Biden have returned a centre-Left party to power in the United States, buoyed by a Democratic majority in Congress and the Senate (though the first is thin and the second is only a single vote). The Democrats’ opponents in the Republican party, meanwhile, are poised for an internal struggle over its future direction and character—the raucous belligerence of the Trumpism to which it has lately become accustomed, or moderation that allows for robust opposition and the prospect of deals with a new president whose record suggests he’ll oblige, at least on some issues.

The solidity of Biden’s future governance is restricted, however, to the slender majorities the Democrats have managed to secure in Washington. If Trump does decide to remain in politics, boosted by a losing vote higher than any Republican candidate had received in the past, his base will remain, in substantial part, angry, disaffected, and militant. As at least two polls have shown, they are as likely to believe that Trump did win the election, as that Biden did.

The new president will meet resistance from its own Left as well as from the Right. The Democratic party’s radical wing, which mostly set aside its many differences with Biden during his contest with Trump, wants a more rapid pace of change than the 78-year old centrist would wish. Bernie Sanders, 80 in November and the survivor of a heart attack in October 2019, will likely fade from active politics. But the senior Massachusetts senator and Wall Street foe Elizabeth Warren, who campaigned hard against Biden from the Left, won’t, and it is likely to push him hard. Inside the party, the telegenic 31-year old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez leads “The Squad,” a group of five recently elected members of Congress who hope to build a socialist presence within the Democratic Party. Outside of it, a large part of the activist base has adopted a series of extreme positions on flashpoint issues like race, gender, and criminal justice that are unlikely to find broad support from the US electorate.

It’s become conventional to believe, in part because of the rise of the new far-Left, that social democracy is in terminal decline. In France, the Socialist Party is on the floor. In Australia, Labour remains the main opposition force, but polling shows it has the lowest level of support it’s had for many years. In Israel, the Left has been a spent force since the Second Intifada and the centre-Left has—to date—been unable to convince voters that it offers a better vision of the future than Benjamin Netanyahu. In Germany’s latest polls of voting intention, the Social Democrats are at their lowest ebb on 11 percent, below the resurgent Greens on 31 percent, the Christian Democrats on 30 percent, and even below the far-Right Alternative fur Deutschland, on 12 percent. Although the Social Democrats presently hold power in government in Sweden, they are losing popularity to the centre-Right Moderates and the anti-immigrant Swedish Democrats. And in Holland, Labour is polling around eight percent, a little over half of the polling for the far-Right Party for Freedom.

This ground may not be recoverable. Social democratic parties flourished when production was organised in large plants that created labour armies amenable to unionisation. During the post-war period, many of these workers lived in public housing and the state, often in the hands of the Left, greatly expanded the public health, education, and social services to which they were entitled. These workers were not all socialists: working class conservatism was and remains a powerful social and political force in most democracies, as does a general indifference. But they would generally vote for the parties which served their interests—often, the men and women they elected to parliaments were former union leaders and officials, people who had begun on the shop floor or at the shop counter.

The institutions and habits which once defined working class democratic behaviour have worn badly in the last three decades. Globalisation has ensured that the commodities once made by unionised workers earning relatively good salaries have now been replaced by higher quality goods made by workers earning as little as a 10th of the West’s pay packets. Consequently, the institutions which once supported mass left-of-centre parties shrank. Those which remained relatively well supported—including the US Democrats, the Canadian Liberals, the Labour parties in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand—acquired memberships which were increasingly middle class, now outnumbering working class members. Their policies included support for public spending on health, education, and welfare, but their message was increasingly aimed at the highly educated, and at exhorting the lower classes to go to university.

In his new book The Tyranny of Merit, American philosopher Michael Sandel argues that these developments help explain the toxic division that has emerged in wealthy societies:

When meritocratic elites tie success and failure so closely to one’s ability to earn a college degree, they implicitly blame those without one for the harsh conditions they encounter in the global economy… [B]y telling workers that their inadequate education is to blame for their troubles, meritocrats moralize success and failure and unwittingly promote credentialism (the possession of a college degree)—an insidious practice for those who have not been to college.

This phenomenon is by no means confined to the US. In the UK, there used to be a “Red Wall” of safe Labour seats in the Midlands and north of England, where canvassers for other parties were routinely told “we’ve always voted Labour here” before the door closed. But this began to change during the 2010s. In his 2020 book The Fall of the Red Wall, researcher Steve Rayson calls attention to a “growing disconnect that was increasingly finding expression in a new public narrative. Former Labour voters were increasingly sharing stories about the Labour Party’s lack of aspiration for their areas and of taking them for granted. They shared stories about Labour no longer representing their values, stories of betraying them on Brexit and stories of the party looking down on them.”

As a result of these trends, several of the more acute commentators and politicians saw someone like Donald Trump coming. Others identified the dangers posed by “wokeism” before it swept out of university lecture halls and into the West’s elite institutions. But few saw both and understood their implications. One of those who did was the American political philosopher Richard Rorty, who died in 2007. In a series of lectures delivered in 1997, and later in a book entitled Achieving Our Country, Rorty wrote clearly about two movements that he argued were sure to grow.

The stagnation of lower class incomes and the consequent “proletarianisation of the bourgeoisie,” he argued, was “likely to culminate in a bottom-up populist revolt… because a good deal of the insecurity is due to the globalization of the labour market—a trend which can reasonably be expected to accelerate indefinitely.” This was the world in which the young men and women of the 1990s grew up. “One of the scariest social trends,” Rorty notes, “is illustrated by the fact that in 1979, kids from the top socioeconomic quarter of American families were four times more likely to get a college degree than those from the bottom quarter: now they are ten times more likely.” Much the same is true in all advanced states—France’s academically rigorous grandes ecoles were so deeply resented by the gilets jaunes that President Emmanuel Macron announced that he would abolish the most elite among them, the École Nationale d’Administration, at which he himself had been a pupil—only to later abolish that plan in favour of making it more diverse.

Even many of the young people from economically and socially successful families now find themselves struggling. In an attempt to explain the rise of Donald Trump, Chris Buskirk argues that “these are people who were raised mostly by boomer parents to follow the program that worked so well for them: go to college, maybe grad school, trust the plan and you’ll have a life filled with grilling and long weekends. But it hasn’t worked out that way. It’s been tough. And for those that didn’t go to college, it’s even worse.” The more we grasp how alienated a large part of advanced societies are, the more we understand Trump’s success. As his “bottom-up populist revolt” was rising, the new Left was retreating into hermetic language, acute sensitivity to any perceived injury (usually the kind of “injury” caused by speech), and an inquisitorial search for the guilty men of history and those in the present who violated the codes of behaviour and speech they prescribe.

This Left now infests politics and culture and it regards centrist and technocratic politicians with savage contempt. Nor does it have much interest in—or sympathy with—its fellow citizens who have found their lives got harder over the past few decades as the gulf between them and the wealthy and highly educated elites grew. In the universities, this Left has developed whole departments dedicated to gay studies, black studies, women’s history, and migrant studies, some of which offer original and valuable scholarship. But many do not, and instead repurpose the tools and privileges of academia for the ends of polemic and blame. As Rorty drily observed, “Nobody is setting up a programme in unemployed studies, homeless studies, or trailer park studies because the unemployed, the homeless, and the residents of trailer parks are not ‘other’ in the relevant sense.” Those identified as marginalised or suffering from discrimination are objects of concern and study. The white lower classes, meanwhile, are more often objects of suspicion or even contempt.

Rorty defended a position which is still despised on the Left, especially the far-Left. Heinously for a liberal intellectual, he insisted that a measure of love for one’s country is a necessary precondition for reform—a belief that, even when policies are found wanting or projects have failed, the nation state and its citizens are worth the effort activists make to bring about change. Quoting the historian Nelson Lichtenstein, he wrote that “all of America’s great reform movements, from the crusade against slavery to the labour upsurge in the 1930s, defined themselves as champions of a moral and patriotic nationalism which they counterposed to the parochial and selfish elites which stood athwart their vision of a virtuous society.” To excoriate this “moral nationalism” and take refuge in spectatorship and incomprehensible theory, as the new far-Left were already doing by the late 90s in ever-greater numbers, meant the end of a politics of reason, intelligibility, and engagement with the problems of fellow citizens. “Insofar as a Left becomes spectatorial and retrospective,” he warned, “it ceases to be a Left.”

Those who strive to improve the lot of their fellow humans must work with them in plain language as they undertake with the slow, frustrating work of incremental social and political reform. Most people strive to make the best of the hand fate has dealt them within the society in which they find themselves. Those exhorted to support radical change meant to improve their lives have to understand what that change will mean, what disruption it will cause, and what the chances are that it will deliver success and future stability. They have much to lose by upending the status quo, even if that status quo is resented. The reforms which succeed are those supported and developed by people who believe they will benefit most from them. For the hard-pressed, adventures in the economy or society are more of a threat than a promise.

Life for many in advanced societies may be oppressive or unfair, but it is at least fairly stable. “The public,” Rorty wrote, “sensibly has no interest in getting rid of capitalism until it is offered details about the alternatives.” If the public is told it needs to be liberated from elite technocrats and empowered to establish local institutions of power and decision-making, it will not “be interested in participatory democracy… until it is told how deliberative assemblies will acquire the same know-how which only the technocrats presently possess.” Those who would change society need to contend with the conservatism that resists large visions of a better future. Too often, these turn out to be intellectual illusions that are rarely popular with working people.

Visions are sublime; social reform is messy. Reformist leaders take two steps forward then one step back, or vice versa; they compromise with those they oppose, and sometimes acquiesce in order to enlist their support for a project they feel to be more important. This is democratic politics as we know it, and it is a politics which the newly radicalised Left, gathering strength and conviction as Rorty delivered his lectures, disdains. The aridity of the new far-Left’s convoluted and abstract academic prose and the determination with which its activists turn politics into a zero-sum blame game are both doing enormous harm. If politics is to be worth anything, it has to be about getting things done, not because activists despise their country, but because they love it and believe that it can be better.

It now falls to the centrist, liberal, and social democratic parties to retie the frayed bonds between the working and middle classes. The former are no longer, for the most part, organised in trade unions, and the latter now make up the majority in left-liberal party organisations increasingly dependent on financial support from liberals in business and finance. This is particularly the case in the US. Such relationships are profitable for the parties and their leaders in the short term: Bill and Hillary Clinton, in the 15 years between 2001 and 2016, when the latter launched her presidential bid, earned more than $150m in speaking fees. For that bid, Hillary raised, in various ways, around $1bn, mainly from wealthy donors.

Great wealth and unaccountable power have been targets of left-wing consternation for decades. Now, the centre-Left parties find themselves without a stable base because they have become too greedy for the former and too entwined with the latter. With populism in America now defeated at the ballot box, it remains to be seen whether Biden and the Democrats have the imagination and the wisdom to formulate a new direction that can unite the country, as its new president has pledged.