Immigration

A Loss of Direction and the Rise of Populisms

There is nevertheless a glimmer of hope—the possibility that, despite recent calamities, we are in fact still living in the Age of Moderation and that this is a blip and not an epochal change

Since the end of World War II, we have mostly been living in the Age of Moderation—an epoch characterized by middle-of-the-road politics, in which a moderate Left and Right pursued partially overlapping policies. This long period configured our political compass toward compromise, but that compass now is swinging wildly, back and forth. The general consensus is that this loss of direction is due to the rise of populisms; a revolt against the elites in the name of the people.

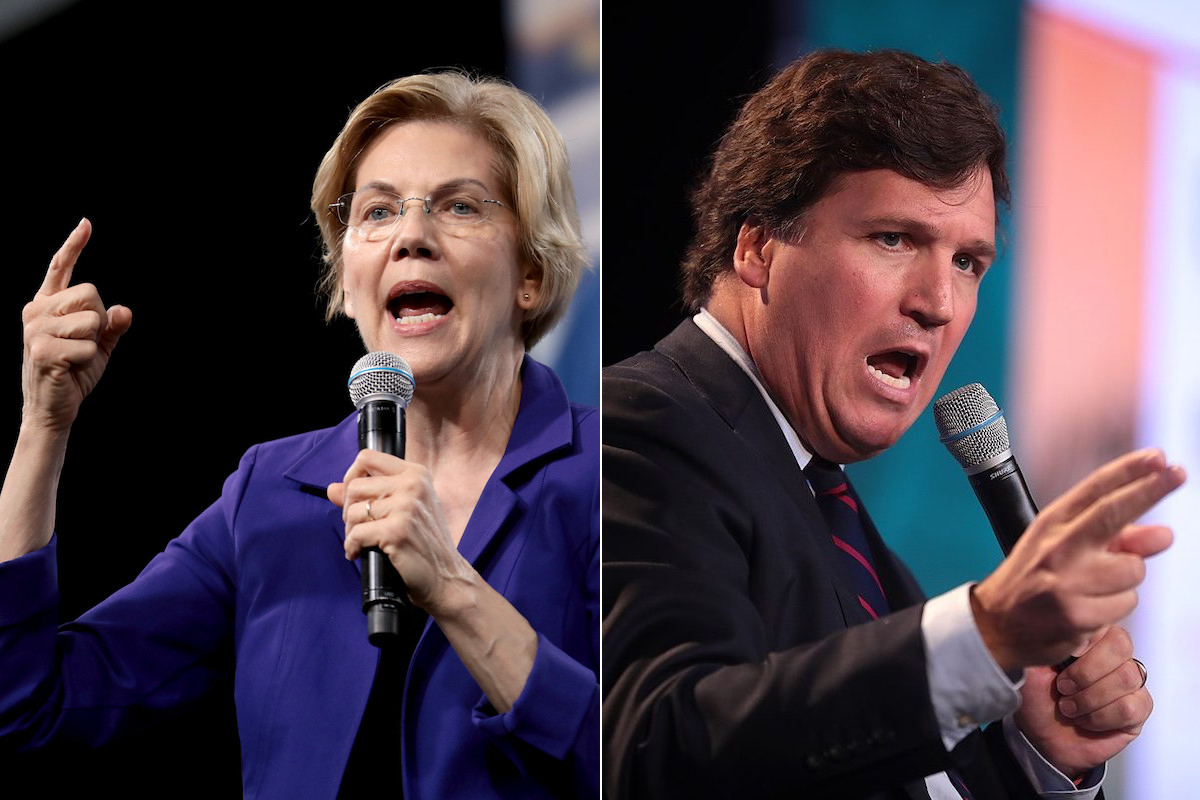

There are two competing populisms, both of which condemn the prevailing neoliberal order. Right-wing populists claim they ventriloquize the concerns of a religious, moral, and hardworking but silent majority. They are perceived by the political center as the primitive ghosts from an unenlightened past. Left-wing populists demand more progressive welfare-oriented policies, total “equality” and an end to “repression” under the label of democratic socialism. The political center views left-wing populism as a mortal danger to the delicate mixed economy.

These two populisms are engaged in a bitter struggle, and both battle the mainstream moderate Left and Right. For many people, this configuration is horrifyingly reminiscent of the fatal internecine struggles of the interwar years. But we are not witnessing a simple resurrection of the radicalization of the interwar years. We are in another age: Repolarization is the consequence of the cul-de-sac of the Age of Moderation. In order to understand how this came about, we should review our historic trajectory—how the political compass of the West was shaped by the initial combat between Left and Right, how and why it moderated, and how this compromise fell into crisis.

Once upon a time…

In the mid-19th century, the Left became synonymous with the revolutionary Marxist socialist workers’ movement. Marxism radicalized the heritage of Rousseauian thought, which identified private property as the cause of all the ailments and injustices in human society. The Marxist Left turned against the market-oriented laissez-faire Scottish Enlightenment, which was the polestar of the political Right.

The Marxist Left preached on behalf of a downtrodden proletariat, the hardworking people who did not have enough to eat at the end of a hard day’s work. The Right, meanwhile, defended the upper echelons of society, traditional values, religion, and the educated and civilized middle-classes. Marxists wanted to socialize the means of production; the Right defended private property. The Left preached “real democracy” after the inevitable revolutionary toppling of the oligarchic sham democracy of the bourgeoisie; the Right defended the “representative democracy” of the propertied classes and the educated elite. The Left was radical, if not revolutionary. The Right was conservative, if not reactionary. The Left demanded a secular ethos to destroy traditional society, while the Right defended and based itself on that divine order.

This adversarial Left-Right divide shaped the political history of the modern age and our political compass: the class and culture war between Left and Right. However, in the last decades of the 19th century, there began a partial depolarization and programmatic overlap between Right and Left, and the seeds of moderation and compromise began to sprout between them. Each country has its own history of increasing moderation, compromise, and diminished class warfare. Here, we will focus on Germany because the developments there had a great impact on the Western World, including the US.

The momentous reconfiguration of Germany

In the 1870s, Otto von Bismarck, the conservative Iron Chancellor, ditched the free marketeers and created the welfare state. His aim was to ameliorate the insecurity and poverty of the lower classes and to forge a unified society. This also, and not incidentally, amounted to taking wind from the sails of the socialists by buying off workers. Inter alia, Bismarck fostered the internal cartelization of the economy by big corporations and erected customs walls to defend German producers. He aimed to pursue the grand historic goal of the nation by reinforcing the industrial capacity of Germany, while maintaining traditional national order. Germany created this new model of the state-regulated market, balanced on the one hand by collaboration between organized labor and business, and on the other by the welfare state. It developed the modern state that combines the welfare state, the regulative state, and the developmental state within the context of a mixed economy and class compromise.

This German Model became, in one way or another, the political model that the mainstream centre-right parties followed in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The trend of the Right towards embracing the ameliorative role of the state was reinforced by the rise of Christian socialism and neo-Calvinism. The Encyclical Rerum Novarum, issued by Pope Leo XIII in 1891, called for concerted action to alleviate “the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class.” At the same time, the Right increasingly accepted the extension of suffrage based on the hope that the peasantry, smallholders, and some of the working class would support right-wing parties due to their religious beliefs and nationalistic worldview. All in all, major right-wing parties increasingly strove to gain the status of “people’s parties” in competition with the social democrats, who claimed to represent “the people.” It is symbolic, and representative of these monumental changes that, today, the EU’s right-wing centrist party is named the European People’s Party.

A good decade later, in the late 1880s, the social-democratic Left also made its own compromise with capitalism under the influence of the reformist Eduard Bernstein. His program aimed to reform capitalism through extension of the welfare state. He ditched revolutionary Marxism and embraced democratic elections as a means to power. As a consequence, the Left—first reluctantly, and then whole-heartedly—embraced the welfare state and the goal of making capitalist society fairer and more egalitarian through progressive taxation, regulation, and redistribution, instead of eradicating markets and capitalists.

With this shift towards the center, the Left struck up an alliance with the anti-feudal and pro-modernization progressive liberal educated and secular urban middle classes. These middle classes professed social liberalism, that centred on giving a chance of life to all through the welfare state and public education, while eradicating the vestiges of feudalism. They especially resisted the kind of nationalism which they saw as a sentiment propagated by the traditional ruling classes to legitimize their dominant position in society. And they aimed to limit the greed and power of plutocratic capitalists and thus became somewhat influenced by Marxist anti-capitalist sentiment. Partly due to the cultural commitment to secularism and anti-nationalism, the base of the Left was concentrated in the metropolitan and urban centers.

The secularism and anti-nationalism of this new Left was particularly attractive to the newly assimilated urban Jewry, and the Left and progressive liberalism became increasingly associated with Jewishness. This realignment gave an additional layer of meaning to the Right-Left divide in Germany, and in those other countries where Jewry had a significant presence in modern urban economies. Traditional anti-Semitism acquired a new meaning. Radicals on the Right began to claim to represent the Christian Nation and turned against the “Jewish” Left and liberal progressives. Anti-Semitism also received some support from traditional elites—who felt threatened by the Jewish elite and Jewish capitalists—and increasingly became a unifying and convenient “populist” cover to unify the tensions polarizing the rapidly modernizing societies of the belle epoque.

Nevertheless, anti-Semitism was for now still a rather marginal affair and the re-rapprochement between Left and Right proceeded slowly and haltingly. Moderation seemed to be unstoppable. The West seemed to be about to enter into the age of electoral competition between moderate Right and moderate Left Peoples’ Parties.

The collapse of the belle epoque

Everything changed with World War I. The horror, the suffering, and impoverishment that conflict created led to political destabilization. There was an especially grave crisis in Russia, Germany, and in Italy. This opened the gates to left-wing popular uprisings aimed at establishing popular democracy. The communist revolutionaries aimed to end the bourgeois order altogether and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat, despite the fact that they were mostly well-educated sons and daughters of good families, who reserved for themselves the power to remake society based on their ideas. The first country where communists came into power was czarist Russia, which was transformed into the Soviet Union.

Many of the communist leaders were assimilated Jews. As a consequence, anti-Semitism was embraced by the higher echelons of traditional society, who had been allied with elite assimilated urban Jewry in the pre-war period, but were now offended by what they saw as a breach of the gentlemen’s agreement—that statecraft was their dominion. This anti-Semitism became especially pronounced in the officers’ corps of the armed forces. Communist radicalism—the betrayal of democratic promises and the bloody nature of communist revolts—had terrified and radicalized the majority of society which wanted to restore order. These sentiments coalesced into the birth of popular right-wing extremism, fascism, and national socialism, partly fostered also by the deeply felt injustices in the peace treaties inflicted upon Germany, Italy, and Hungary.

This sudden and unprecedented radicalization on both the Left and the Right interrupted the process of moderation. A split arose between reformist social democrats and communists on the Left, and between conservatives and radicals on the Right, while Left and Right fought one another. After 1921, however, there began a new consolidation period and moderation made a tentative return. The Great Depression, however, again fanned the flames of extremism, aggressive nationalism, and anti-Semitism. The Nazi takeover of Germany led to total destabilization with horrendous consequences for the entire world. The blood, sweat, tears, and nightmare horrors of the Second World War were a watershed that shaped the post-war Western world.

The Great Moderation in the post-World War II period

A new world order arose in the aftermath of World War II: The Age of Great Moderation. “Never Again!” promised those who survived the war. We shall never allow extreme nationalism, political extremism, and economic crises to set the world aflame. The dream of moderation became an antidote to both right- and left-wing extremism, and ushered in political, attitudinal, and economic reforms.

Politically, universal suffrage became accepted across the Western world. The age of the People’s Parties returned and consolidated. Being in government required respecting the right of the opposition to win the next election.

The second major change involved political attitudes and rhetoric. Moderate Left and Right had both learned the dangers of domestic warmongering by radicalized leaders and political prophets and sidelined them. The established moderate parties resolved to accept each other as legitimate political parties and hold the democratic center at any cost. As a part of this process, social democratic parties officially shed the last vestiges of orthodox Marxism, although many social democrats continued to believe in some Marxist concepts.

The third reform was the universal adoption of Keynesianism. In practice, this made the state the most significant player in the economy and society at large. Moderate political parties on the Right and Left all competed with one another about how to extend the welfare state and made more and more promises about caring and governing for the people.

This moderation flourished under the American security umbrella, which to a large extent closed down the political competition between Left and Right over geopolitical alignment to East or West. All the major parties became centrist, liberal, and moderate People’s Parties—in an effort to capture the votes of the majority, they made extravagant welfare promises, while opting for a mixed economy with a heavy emphasis on the state as the moderator, arbiter, and rule-maker.

A new Golden Age had arisen in which a substantial majority of voters could improve their own material situation as the state provided them with pensions, welfare payments, and various public services. Greatly expanded public education—especially higher education—opened up new mobility channels. Business also banked on state regulation, special tariffs, public tenders, and various support schemes to ensure a secure profit, and an entrenched position in the market. Educated progressive technocrats occupied the key administrative positions within the expanding state bureaucracy. Greatly expanded budgets and the penetration of the government in all areas of life enhanced the influence of the almighty state.

The expansion of the welfare state created and was created for the large and dominant new consumer middle class, which became the center of and the majority in modern Western nations. The melting pot of the new consumer middle class had swollen to such a large extent that it nearly drove out of existence the class and status tensions among and between the peasantry, the urban proletariat, petty and high bourgeoise, Jews, men and women, and the nobility. The by-and-large disappearance of these societal tensions, which fuelled in various guises the bitter historic division between Left and Right, heralded the winning of a materialistic version of liberté, égalité, fraternité, the clarion call of the French revolution. The Age of Moderation seemed to solve the tensions of modernized societies, which had caused so much tragedy in the first half of the 20th century.

The end of the road

Across the world and in the US in particular, the 2008 financial crisis changed the tune and brought the Age of Moderation to a profound crisis. The crisis, however, has deeper causes than the rise of populists, and can be summarized as follows:

First, “progress” did not provide a ladder to Heaven. Neither poverty nor ill-health nor unemployment, homelessness, or racial inequality were banished by the extension of the welfare state.

Second, although a secularization of public life and a legislative legitimization of individual lifestyle choices accompanied the decline of organized religion, among large segments of the population strong religious beliefs and traditions remained entrenched. Not insignificant parts of the population became alarmed by the retreat of religion and traditional morality as a guide to behavior and civil order.

Third, the “democratic” redistribution of power was largely illusory, as the elites managed to retain control of society, largely through their social position and access to elite schools, which allowed them to steer the machinery of the state. The educated oligarchic elite rule fueled populist movements, which demanded “real” democracy and “draining the swamp.”

Fourth, the growth of the state had probably reached its economic and politically expedient limit within the context of a mixed economy. Redistribution reached around half of GDP; taxes reached about half of all income. The debt level became astronomical. Regulation became widely regarded as overly burdensome and cost-increasing. The escape of manufacturing to low-wage and loosely regulated countries signaled a loss of competitiveness. It became difficult to implement any new large-scale extension of welfare measures. The credibility of mainstream parties eroded as they continued to promise heaven in election campaigns, while making cost-cutting reforms in government.

Fifth, the evolution of consumer society with attendant increased waste and garbage, raised the specter of human-caused Global Warming and environmental degradation.

Sixth, the rise of China, due in part to its immense size and dynamism, heralded a shift of dominant power in the world and created anxiety about Western decline.

Seventh, the great amelioration became threatened by drastically lower birth rates. The sustainability of the welfare state is now threatened by rapidly aging populations.

Eighth, this demographic decline was accompanied by increasing immigration into the West, which opened new political and cultural divisions, especially in Europe. The religiosity of Muslim newcomers reignited the dormant and historically significant religious and cultural animosities held with deep conviction by a part of the population. The association of Muslim migration with terrorism, sex crimes, and anti-Semitism also raised the specter of fear and provided an easily exploitable issue. Immigration provoked fear and anger among large segments of society and drew together urban lower middle classes and traditionalist rural and small-town dwellers, who felt threatened by a large influx of immigrants aided by multicultural metropolitan elites.

Finally, identity politics, widely embraced by the progressive Left, placed the blame for all society’s ills on white male bigotries creating wrathful resentment among the lower middle- and working-class whites who felt increasingly betrayed by the progressive elites.

The nine changes listed above largely immobilized the program of the mainstream moderate parties. The stage was therefore set for a populist revolt that would attack the neoliberal pro-globalization consensus of mainstream parties, the prevailing oligarchic order, and the perceived moral decay and immorality. The divisions over immigration and family models provided a springboard for populists. Thoughts banned by political correctness and moderation reappeared.

The new radical Left has rediscovered the word socialism, which had long been banished from civil discourse. And it has begun to issue demands for radical equality, steeply progressive taxation, immigration, lifestyle freedom, identity politics, reparations, aggressive secularism, anti-religiosity, and anti-nationalism. For them, democratic socialism offers the possibility of advancing beyond the presumptive limit of a capitalist mixed economy. They propose increased redistribution at the expense of billionaires and the breakup of the concentration of capitalism.

The new populist Right is resurrecting the concept of nationhood based on divine right. They insist on the primacy of national and cultural sovereignty and agitate against foreign exploitation. They defend the productive capacity of the nation and those who “produce.” They especially oppose immigration. They defend the lifestyle traditionalism of the lower hard-working middle class and seek to revive the “forgotten” traditions of family, especially those producing the children needed for demographic rejuvenation. They say that only they utter the truth, by breaking the taboos imposed on them by the hegemonic political correctness of the globalized progressive liberal elite.

Culturally, both populisms resurrect nostalgic memories of the past, and both appeal to the hearts of ordinary people, whose family traditions bequeathed familiar slogans and cultural patterns. Just what grandma, granddad, mommy, and daddy used to say! The emergence of populisms with their political messages has caused a surprising new reconfiguration of political messages and voting bases to emerge.

The new populist Left is representing the ideas of the cosmopolitan educated progressive upper middle classes—their quest for lifestyle freedom and the redistribution of resources to the poorest. They turn against the perceived selfishness, traditionalism, and nationalism of the white lower middle classes of their own society, while they preach compassion for all the wretched of the Earth and call for the erasure of national borders. Characteristically, they live in elite districts and have jobs that are not threatened by undereducated immigrants. The populist Left have rendered certain words, phrases, and ideas taboo, and denigrate white males as a morally inferior but powerful-by-mere-privilege class of beings. This is a dagger in the heart of the white working class, who were once the object of the Left’s attentions.

In contrast, the new populist Right preaches on behalf of the downtrodden and abandoned hard-working lower middle class of the nation, who feel threatened by globalization and by immigration. They agitate against the multicultural educated upper middle class that runs the show. The populist Right not only receives the support of much of the former working class, but also relies on the traditional religious middle classes and the rural population. This has created a coalition once dreamed of by Lenin—the hammer and sickle led by scions of the middle class.

This surprising realignment is causing considerable confusion. The slogans of the new populists are reminiscent of the historical Left and the radical Right, but to a large extent they have switched positions. The Left became the voice of the educated progressive urban upper middle classes. The populist Right became radical—if not revolutionary—against the straitjacket of the progressive and secular order. For the moderate mainstream, the slogans of the new radical populists are the nightmare memories of the extremism of the totalitarian regimes thought to have been conquered by the heroes of the Greatest Generation.

Hence the aggressive polarization. Fear, anger, rage, hatred, and fury are turning to wrath, and the demonization of opponents. Political crisis is palpable. Political antipathy is so deep that even families and friendships are being torn apart. Each side is preparing itself with fear and dogmatic righteousness for the final Armageddon for the Soul of the Nation. Voters and governments alike are divided as to what to do about immigration and demography and are unable to shed the protective mantle of the paternalistic state and renounce its perks. Meanwhile, the competitive pressure of the recently “marketized” economies of the East threaten the preeminent position of the West.

Part of the reason for this dysfunction is that voters in the West are still, by and large, living the dream of consumer paradise in a pampered world. But they also feel ashamed of the despoilation of the planet, of their wealth compared to the poverty of the “Global South,” and their privilege compared to the plight of the exploited minorities on the wrong side of town. Nevertheless, they still want to consume more and crave the latest technological innovations. That dream world is being disturbed from every direction. They just don’t know who to trust to ensure a “good life” or who will care about their future. This is life at the cul-de-sac of the belle epoque of The Great Moderation.

And then came COVID…

The COVID-19 pandemic has upset the earlier uneasy coexistence of accepted “truth” and the occasional revolts against it. What was considered a radical economic populist agenda just six months ago has won: Budget constraints are ignored or even not deemed to be constraints anymore. Economies have slowed dramatically due to lockdowns and fear of illness, and the state is now expected to revive them using state funding, debt creation, and welfare programs. Central banks have embarked again on large-scale money creation to push the economy over the deflationary precipice and avoid collapse.

Despite the unprecedented scale of state intervention, the recovery from the novel coronavirus lockdowns is slow and partial. Immense difficulties lie ahead. No wonder, then, that the cultural-political differences have become even more vicious. Nonetheless, we are nowhere near an explosion comparable to the interwar years. This is not 1933. Rather, we are in the fateful last years of the belle epoque, the underlying contradictions of which led to an unexpected eruption of the Great War in 1914. This situation bears an uncanny resemblance to the world described by Thomas Mann in The Magic Mountain—an impending sense of doom, of the end days, combined with an epidemic.

Just as then, we have three major sources of conflict. First, an underlying Great Power competition between China and the US. Second, the unsustainability of the mixed economy in the context of the large increases in debt and aging populations. Finally, the revolt of the young educated sons and daughters of bourgeoisie families against capitalism could yet have fateful consequences, as occurred in the interwar period. Very difficult years lie ahead. There is nevertheless a glimmer of hope—the possibility that, despite recent calamities, we are in fact still living in the Age of Moderation and that this is a blip and not an epochal change. If we keep our nerve and work back towards consensus and understanding, hopefully we can muddle through without setting the world aflame.