recent

Economic Inequality—Populism’s Rallying Cry

The inequality narrative’s major flaw is that it fails to assess the only dimension of prosperity that really matters, absolute prosperity, choosing instead to focus on relative prosperity.

A nation will not survive morally or economically when so few have so much, while so many have so little. We need a tax system… which reduces the obscene degree of wealth inequality in America.

~Bernie Sanders

[A]ffluent married people, the ones making virtually all the decisions in our society, are doing pretty much nothing to help the people below them… Rich people are happy to fight malaria in Congo. But working to raise men’s wages in Dayton or Detroit? That’s crazy. This is negligence on a massive scale.

~Tucker Carlson

Populists on both the Left and Right have a narrative to push. According to this narrative, when economic inequality rises, the middle class suffers and the American dream dissipates. When the government combats inequality, conversely, the middle class rises and the American dream prospers. Let us call this the inequality fable. It is a tale the Left has been telling for over a century, though patriotic Americans on both sides of the aisle have been rallying around it with passionate intensity since the Great Recession of 2007, facts be damned. The full story, a Rousseauian mythos complete with historical revisionism and a dose of nostalgia, is summed-up well by former labor secretary Robert Reich in his book Beyond Outrage:

The old view was that anyone could make it in America with enough guts and gumption. We believed in the self-made man (or, more recently woman) who rose from rags to riches: inventors and entrepreneurs born into poverty, stories that proved the American dream was open to anyone who worked hard. A profound change has come over America. Guts, gumption, and hard work don’t seem to pay off as they once did—or at least as they did in our national morality play. Instead, the game seems rigged in favor of people who are already rich and powerful…. Instead of lionizing the rich, we’re beginning to suspect they gained their wealth by ripping us off.

Notice that Reich calls his narrative a “morality play” in which hard work doesn’t “seem to pay off” and in which “the game seems rigged.” Reich and other inequality critics, including those on the Right, all tend to have one thing in common: Despite their divergence on a myriad of social issues, they give us a romantic vision of the past and urge us to “Make America Great Again.”

Reich, Sanders, and Warren do not put it in those terms because to do so would be political suicide, but their message is fundamentally the same. After World War II, so the fable goes, America created a “Golden Age” in which stable, well-paid employment, high levels of mobility, and “shared prosperity” were the norm, thanks to a proactive government that took steps to promote economic equality. But over the years, thanks to greed, corruption, Ronald Reagan, and the failures of the unfettered free-market, those days are gone. Since then, “the rich” have rigged the system in their favor, leading to catastrophic levels of inequality. Starting in the early 1980s, the wealthy have captured the bulk of the nation’s economic growth, transferred the tax burden onto the middle class, dismantled the welfare state, and left “the people” out in the cold.

Is it true, as Pope Francis tweeted, that economic inequality is “the root of social evil”?

Inequality is the root of social evil.

— Pope Francis (@Pontifex) April 28, 2014

As it turns out, the inequality narrative has hardly any basis in fact, but is nevertheless the populist’s barbaric yawp. This emotional conviction that inequality or “the system” or “the one percent” is to blame for our problems is belied by nearly all available data. What’s more, argues author Jonah Goldberg in Suicide of the West, it is emblematic of a destructive counter-Enlightenment attitude that is currently back in fashion—romanticism:

The core of romanticism is the primacy of feelings. Specifically, the feeling that the world we live in is not right, that it is unsatisfying and devoid of authenticity and meaning (or simply requires too much of us and there must be an easier way). Because our feelings tell us that the world is out of balance, rigged, artificial, unfair, or—most often—oppressive and exploitative, our natural wiring drives us to the belief that someone must be responsible.

The flaw in “victimhood populism,” a term coined by writer David French, is that it fails to address the agency and responsibility of the individual, railing instead against a vague, indefinable antagonist. Populism, writes French, “tells a fundamentally false story about Americans as victims of a heartless elite and their ‘worship’ of market economics, rather than the true story of America as a flawed society that still grants its citizens access to tremendous opportunity.”

The inequality fable is an emotionally satisfying tale filled with pathos and poignance. Yet it is untrue. While it is true that our nation faces a bevy of serious problems—including climate change, opioid and obesity epidemics, a decreasing life expectancy rate, gun violence, the decline of the family (a third of US children are now raised by single parents), and a looming national debt crisis—inequality, it turns out, is not one of them.

Debunking the Inequality Fable

Let us start with an inarguable fact. The embrace of market capitalism by developing nations around the world is directly responsible for lifting the world out of extreme poverty over the past century. In the year 1800, more than 90 percent of the world lived in extreme poverty; today, thanks to classical liberal economic principles and the industrial revolution, that number is down to less than 10 percent. This is all the more remarkable when we consider that, over this same period of time, the world population has increased more than seven-fold. Sadly, few are acquainted with this fact, and even fewer understand that much of this progress happened in the last 30 years.

As recently as 1980, the World Bank estimated that half of the global population lived in “absolute” poverty ($1.25 per day in 1980 US dollars). In 1990, the World Bank created its Millennium Development Goal: to cut the world poverty rate in half by the year 2015. Although this was an ambitious goal, economists reasoned this could be accomplished by working with developing nations to bring about basic economic freedoms which would foster international trade and freer markets. The economists were right. The World Bank announced in 2010 that it had reached its goal five years early. World poverty had been cut in half. By adopting free market principles and increasing trade partnerships, countries like China, India, and Indonesia—which housed over a third of the world’s extreme poor—were able to industrialize and transform their economies. As countries develop, innovation increases, workers begin to gain more rights, access to medicine increases, and overall living conditions improve. One notable statistic bears this trend out: According to the World Health Organization, “the mortality rate for children under the age of five declined by 49 percent from 1990 to 2013.”

The data on humanity’s great escape from poverty remind us of the fact that poverty, not wealth, is the default condition of life. “In a world governed by entropy and evolution,” writes Steven Pinker in Enlightenment Now, “the streets are not paved with pastry and cooked fish do not land at our feet. But it’s easy to forget this truism and think wealth has always been with us.” For an economist, the right question is not Why is there poverty? or Why is there inequality?, but rather, Why is there wealth? And how do we lift the poor out of poverty? Pinker, a progressive liberal, points out, “The need to explain the creation of wealth is obscured… by political debates within modern societies on how wealth ought to be distributed, which presupposes that wealth worth distributing exists in the first place.” In other words, placing the focus on economic inequality tells us nothing about how to create more wealth, and has been wholly irrelevant to the project of lifting the poor out of poverty.

It is undeniable that economic inequality has increased in the majority of Western countries since its low-point around 1980, especially when we compare the very richest to the rest. As Pinker points out, in the U.S., the share of total income going to the richest one percent went from 8 percent in 1980 to 18 percent in 2015, while the share going to the richest one tenth of one percent went from 2 percent to 8 percent. And yet, because the total amount of wealth has also greatly increased over that time, the poor, despite increased inequality, have become richer and better off by most dimensions since 1980.

This distinction is crucial, although it is one famous French economist Thomas Piketty, whether by accident or design, has failed to acknowledge. While Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century has given the chattering classes a bevy of inequality talking points that sound convincing at cocktail parties, most of them have the unfortunate quality of being wrong, including his claim that “the poorer half of the population are as poor today as they were in the past, with barely 5 percent of total wealth in 2010, just as in 1910.” Here Piketty neglects to mention that total wealth—the “pie”—has greatly increased since 1910, leaving the poor with a much larger slice of pie, even though their percentage of the total pie has not increased. As a result, the poor are much richer today than they were in 1910, which is not to mention that technology has improved and most goods are cheaper, so their standard of living is higher as well.

The Fixed Pie Fallacy

Speaking of pie, conversations about solving “the problem” of economic inequality—i.e. income and/or wealth inequality—are typically products of what economists call the fixed-pie fallacy, the belief that wealth is, in Pinker’s words, “a finite resource like an antelope carcass which has to be divided up in zero-sum fashion so that if some people end up with more, others must have less.” The fixed pie fallacy is the assumption that there is only so much wealth to go around, so that when someone becomes wealthy, it must have come at the expense of someone else. Dan Riffle, an adviser to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), commits this fallacy when he complains that “the bigger Jeff Bezos’s and Bill Gates’s slices of the pie are, the smaller everybody else’s slices of the pie are going to be.” This claim couldn’t be further from the truth. Bezos and Gates have created an enormous amount of wealth, expanding the pie for nearly everyone. Their products and services have streamlined businesses and made them more efficient; not to mention, they have created millions of jobs, both directly and indirectly. The wealth Bezos and Gates created has resulted in billions of dollars of charity as well as the redistribution of billions of tax dollars annually. Gates alone has given nearly $5 billion to charity since the year 2000 through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The fixed pie fallacy ignores the fact of production, the fact that people are always creating new wealth, which is partly why the “one percent” is not a monolithic entity but a constantly shifting one, as “some 11 percent of Americans will join the Top one percent for at least one year during their prime working lives.” A market economy is not a zero-sum game (a fixed pie); it is a positive-sum game (a growing pie). Economic inequality, writes economist Yaron Brook in Equal Is Unfair: America’s Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality, “is perfectly compatible with widespread affluence, and rising inequality is perfectly compatible with a society in which the vast majority of citizens are getting richer. If the incomes of the poorest Americans doubled while the incomes of the richest Americans tripled, that would dramatically increase inequality, even though every single person would be better off.” The term inequality does not mean deprivation; it means difference. It doesn’t refer to the condition or status of anyone’s wealth or welfare; it refers merely to the gap in between. If Suzy and Bill are on an island together and Suzy grows 70 potatoes while Bill grows 30, Suzy hasn’t seized a bigger piece of the pie; she has merely created more wealth than Bill. It would be false to say that Suzy has taken any wealth from Bill or left him worse off, just as it would be false to claim that Suzy has captured 70 percent of the island’s wealth.

Inequality and Wealth

But if wealth is created and can be expanded, if it is not simply a fixed sum divided up equally among a nation’s citizens, then how is wealth created? Wealth is not a finite lode of gold people have been fighting over since the beginning of time. It is created through knowledge, innovation, and cooperative association. “[Wealth] is created by networks of people [who] arrange matter into improbable but useful configurations and combine the fruits of their ingenuity and labor,” explains Pinker. “And we can figure out how to make more of it.” In fact, in a free society that enforces contracts and protects property rights—a free market society—the only way to create wealth is to produce value for others. As political commentator Ben Shapiro has put it in his book And We All Fall Down, “Socialism states that you owe me something simply because I exist. Capitalism, by contrast, results in a sort of reality-forced altruism: I may not want to help you, I may dislike you, but if I don’t give you a product or service you want, I will starve. Voluntary exchange is more moral than forced redistribution.”

In order to get rich in America, you have to produce something of value that other people want. Updating the famous example from philosopher Robert Nozick, Steven Pinker considers the example of J.K. Rowling, author and former billionaire, whose Harry Potter novels have sold over 400 million copies and have since become a film empire:

Suppose that a billion people have handed over $10 each for the pleasure of a Harry Potter paperback or movie ticket, with a tenth of the proceeds going to Rowling. She has become a billionaire, increasing inequality. But she has made people better off, not worse off…. No committee ever judged that she deserved to be that rich. Her wealth arose as a byproduct of the voluntary decisions of billions of book buyers and movie-goers.

As someone who owns all of the Harry Potter books, I can attest that nobody ever forced me to give J.K. Rowling my money. When I purchase one of her books, I gladly fork over $10 because I value the experience of reading and owning the book more than my $10. Likewise, because Rowling’s publishers value my $10 more than the book—given they can produce it cheaply and easily, whereas I cannot—they happily accept my money. Billionaires are created by the voluntary transactions of free individuals.

More Economic Inequality Does Not Mean More Poverty

The level of inequality in a society does not tell us anything about the levels of poverty in that society. In fact, poverty often falls as wealth inequality rises, such as when innovators and entrepreneurs amass wealth by creating value for consumers, which in turn stimulates the economy, generates economic growth, and lowers prices for consumers. When the economy becomes corrupt, or when governments engage in cronyism distorting the economy and reducing growth, poverty can also rise as wealth inequality rises.

The irrelevance of economic inequality to ascertaining the overall welfare—the well-being, prosperity, freedom, or fairness—of a nation can be demonstrated by glancing at a list of the world’s most economically equal countries, as determined by the Gini Index, the measure economists use to track income inequality. The list, you will notice, includes some of the most and least oppressive countries in the world with respect to human rights, and some of the wealthiest and poorest with respect to GDP per capita. While countries many see as egalitarian paradises like Iceland (2), Finland (9), Norway (10), Sweden (11), Belgium (14), and Denmark (15) make the list, so do countries like Czech Republic (4), Kazakhstan (6), Belarus (7), Kosovo (8), Serbia (19), Iraq (20), and Pakistan (23). In fact, taking the number one slot on the list is Ukraine, a former territory of the Soviet Union. Despite the fact that it is “among the poorest nations in Europe” and “suffers from poor infrastructure, bureaucracy, and corruption,” with a Gini Index of 25.5, Ukraine is the most wealth-equal country in the world.

The inequality narrative’s major flaw is that it fails to assess the only dimension of prosperity that really matters, absolute prosperity, choosing instead to focus on relative prosperity. But relative prosperity is irrelevant to human welfare. “What’s relevant to human well-being,” writes Pinker, “is how much people earn, not how high they rank.” Poverty and inequality are two very different things, yet the two terms often get mixed up in political discourse. Poverty is a dire problem any just society should work hard to alleviate. Wealth inequality is different; by itself, it is neither good nor bad, as “it may reflect either a growing economy that is lifting all boats or a shrinking economy” caused by corruption, unequal treatment, or lack of open markets. “Inequality itself,” Princeton philosopher Harry Frankfurt argues in On Inequality, “is not morally objectionable. What is objectionable is poverty. From the point of view of morality, it is not important everyone should have the same. What is morally important is that each should have enough.”

Do all people have enough in the US today? As long as one person doesn’t have enough, we still have work to do as a nation. But the work we do should focus on the alleviation of poverty, which is the real problem, not on eliminating the gaps between what some and others have.

Inequality in America

According to the inequality fable, the rich are not paying their fair share and economic inequality is tearing our society apart, depriving Americans of opportunity and leaving them worse off. So just how bad is inequality in the United States?

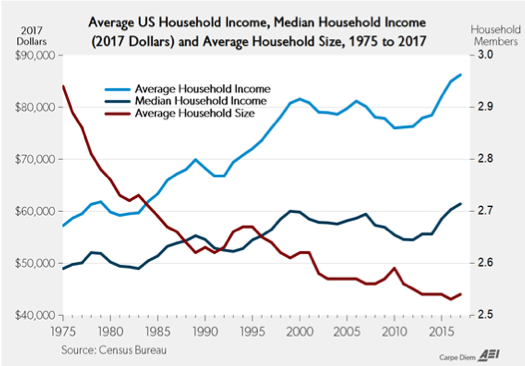

Contrary to popular belief, the rich, beyond expanding the overall pie, also pay more than their “fair share” in taxes. In 2018, the top 20 percent of income earners, although their income makes up only 52 percent of total income in the U.S., paid fully 87 percent of the total income tax, which demonstrates how truly progressive the U.S. income tax rate is. Moreover, while it is true that wealth inequality has risen in recent years, nevertheless, in that same span, the poverty rate has declined. “Meanwhile,” write Chris Edwards and Ryan Bourne at the Cato Institute, “wages are up and unemployment is low.” According to Federal Reserve Board data, “the top one percent wealth share increased slightly between 2013 and 2016, but the wealth of the median household jumped 16 percent over that period, with particularly strong gains by less-educated households.” The following chart illustrates this unsung accomplishment, showing that median and average household incomes have gone substantially up, even as the number of family members living in each household has declined:

As the chart indicates, last year’s median household income of $61,372 was an increase of 1.8 percent from 2016, raising median income for US households to “the highest level ever, above the previous record level last year of $60,309,” according to Mark J. Perry at FEE. Overall, this income gain represents “the fifth consecutive annual increase in real median household income starting in 2013, following five consecutive declines” which were a result of the Great Recession. Even for individuals, or household members, the median income per person in the US reached an all-time high in 2017, increasing from $16,600 in 1975 (adjusted for inflation) to $24,160, an increase of 45 percent.

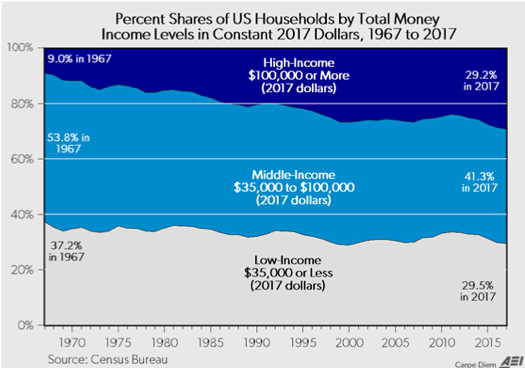

But, but, the populists interject, the middle-class is disappearing! How can these numbers be right? Here the populists are correct. The middle-class is disappearing. But it is disappearing into the higher income brackets, not down into the lower ones. The second chart (below) shows that in 1967, only 9 percent of US households earned $100,000 or more (in 2017 dollars); by 2017, 29.2 percent of U.S. households—that is more than one in four—earned $100,000 or more. This means that in a half century, the share of high-income households in the US has more than tripled. Meanwhile, the percentage of low-income households (those earning $35,000 or less) has decreased from 37.2 percent in 1967 to 29.5 percent in 2017. In other words, the middle-class is disappearing into the upper-class; and the lower-class is disappearing into the middle-class.

What about the poor in the US? While one person living in poverty is too many, the data show there is room for optimism. The data also prove that the romantic nostalgia demonstrated by the likes of Trump and Warren is misguided and undercuts the progress we have made. The 1950s, that oft-cited decade of unity and shared prosperity, was no party for low-income Americans, not to mention racial and religious minorities. The historian Stephanie Coontz makes this point in her book The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap: “A full 25 percent of Americans, 40–50 million people, were poor in the mid-1950s,” Coontz

writes. “Even at the end of the 1950s, a third of American children were poor, 60 percent of Americans over 65 had incomes below $1,000 in 1958, considerably below the $3,000–$10,000 level considered to represent middle class status. A majority of elders also lacked medical insurance. Only half the population had savings in 1959.” Thankfully, those days are behind us, and we are living in a time of material wealth and prosperity that the Greatest Generation could scarcely have imagined.

The sociologist Christopher Jencks has shown that when you count the benefits US citizens receive in welfare and factor the improving quality and falling prices of consumer goods into the cost of living, the poverty rate has declined in the past 50 years by more than three quarters, an outcome that has been replicated by other scholars. Moreover, Pinker reminds us that when poverty is not defined by what people earn, but what they consume, we find that the poverty rate has declined by 90 percent since just 1960, from 30 percent of the population to just 3 percent.

But still, are we lagging behind the rest of the world? A recent Pew study “How Americans Compare with the Global Middle Class” found that 95 percent of Americans are at the middle income level or better by global standards; 88 percent are upper-middle income or better; and 56 percent are rich. Whereas only 5 percent span from “low-income” to “poor.” The Heritage Foundation corroborated this finding in their own study, adding that the typical “poor” household in America is comparatively wealthy by world historical standards and rarely if ever goes hungry, a status the poorest in most other countries cannot claim.

Using Census Bureau data, the researchers found that “the typical poor household, as defined by the government, has a car and air conditioning, two color televisions, cable or satellite TV, a DVD player, and a VCR,” goods even the wealthiest were lacking a century ago. By the Bureau’s own report, the typical poor family “was not hungry, was able to obtain medical care when needed,” and “has more living space in his home than the average (non-poor) European.” Even when we turn to the poorest among us, the unsheltered homeless (many of whom suffer from mental illness and/or addiction) “fell in number between 2007 and 2015 by almost a third, despite the Great Recession.”

Inequality Does Not Corrupt the Political Process

Since the Occupy Wall Street movement, many on the Left have come to believe, without much evidence, that economic inequality is eroding our democracy. However, the best research indicates that people do not simply vote on their own economic self-interest, but based on many factors, including “ideological beliefs, personalities of politicians, and the stances of their favored parties, which stand on a bundle of electoral promises.” There is scant evidence to suggest that economic inequality results in political outcomes that are somehow less representative of ordinary people’s interests, goals, and ideological concerns. That special interests influence politics is unremarkable and unlikely ever to change, especially because such lobbying typically comes from organized groups representing large blocks of voters, such as unions and industries.

While Democrats are quick to condemn the Koch brothers for spending money on libertarian causes, they seem to have no problem with the immense sums that labor unions spend to influence American politics. “[From] 2002 through 2014,” writes David French at National Review, “unions accounted for seven of the top ten ‘organization contributors’… with roughly 99 percent of contributions going to Democrats.” A major study by Stephen Ansolabehere, John de Figueiredo, and James Snyder Jr. analyzed 40 statistical studies on the effects of campaign contributions on voting in Congress. “Contributions,” they write, “show relatively few effects on voting behavior. In three out of four instances, campaign contributions had no statistically significant effects on legislation.”

Progressives also worry that inequality will result in cuts to social programs, as the wealthy will use their influence and political power to slash welfare. Yet, as wealth inequality has grown, federal social spending has increased, with “total federal and state social spending as a share of GDP” rising “from 9.6 percent in 1980 to 14.3 percent by 2018.”

Conclusion

One common characteristic of populists is the repeated insistence that if we just give them enough power, if we only put the state apparatus in their hands, they can solve all of our problems. “Nobody knows the system better than me,” said Trump in his presidential nomination acceptance speech, “which is why I alone can fix it.” In a similar vein, Elizabeth Warren announced: “You’ve got things that are broken in your life; I’ll tell you exactly why. It’s because giant corporations, billionaires have seized our government.” The problem with these demagogic appeals is that they are typically issued without evidence.

As with Marxism, populism starts by dividing citizens into two classes: oppressor and oppressed. For Trump, the oppressors are the elites, “the swamp,” the deep state, globalists, immigrants, and free traders. For Warren and Sanders, the oppressors are the one percent, “big tech,” Wall Street, the “billionaire class,” corporations, and free traders. In both cases, the oppressed is made up of a base of supporters—“the people”—who have been victimized by the supposed oppressors. For the populist demagogue to gain power, he or she must convince the people that they are, in fact, oppressed. This is not an easy task in the freest, most prosperous nation in the history of the world. The most effective solution, then, is the inequality fable.

When demagogues cite economic disparities as a reason for revolution, the intention is to pit citizens against one another, which doesn’t help the average American but only whips up feelings of anger and resentment, giving demagogues more power. There is no doubt that some people in America experience injustice, and to the extent that injustice is occurring we should tackle it using our legal system. Yet disparities alone do not imply that injustice has occurred. “Disparate outcomes,” as all economists know, “do not imply disparate treatment.” In a free society, the reasons for inequality are varied, but they are also largely natural and immutable. So much so that economists have discovered a law, the Pareto principle (the 80/20 principle or “law of the vital few”), that demonstrates just how deep inequality runs.

Inequality, in other words, cannot simply be laid at the feet of capitalism; it is a “statistical power law,” a neutral fact of life. But the danger of attacking income inequality, rather than poverty, is that it can cause us to place our focus on tearing down the rich—the investors, innovators, builders, movers, and wealth creators—in turn making it all the harder to lift up the poor.