History

The Dead Are Rising—A Review

The Dead are Arising offers similarly interesting insights into Malcolm X’s adolescence and adult life.

A review of The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les Payne and Tamara Payne. Liveright Press, 640 pages (October 2020)

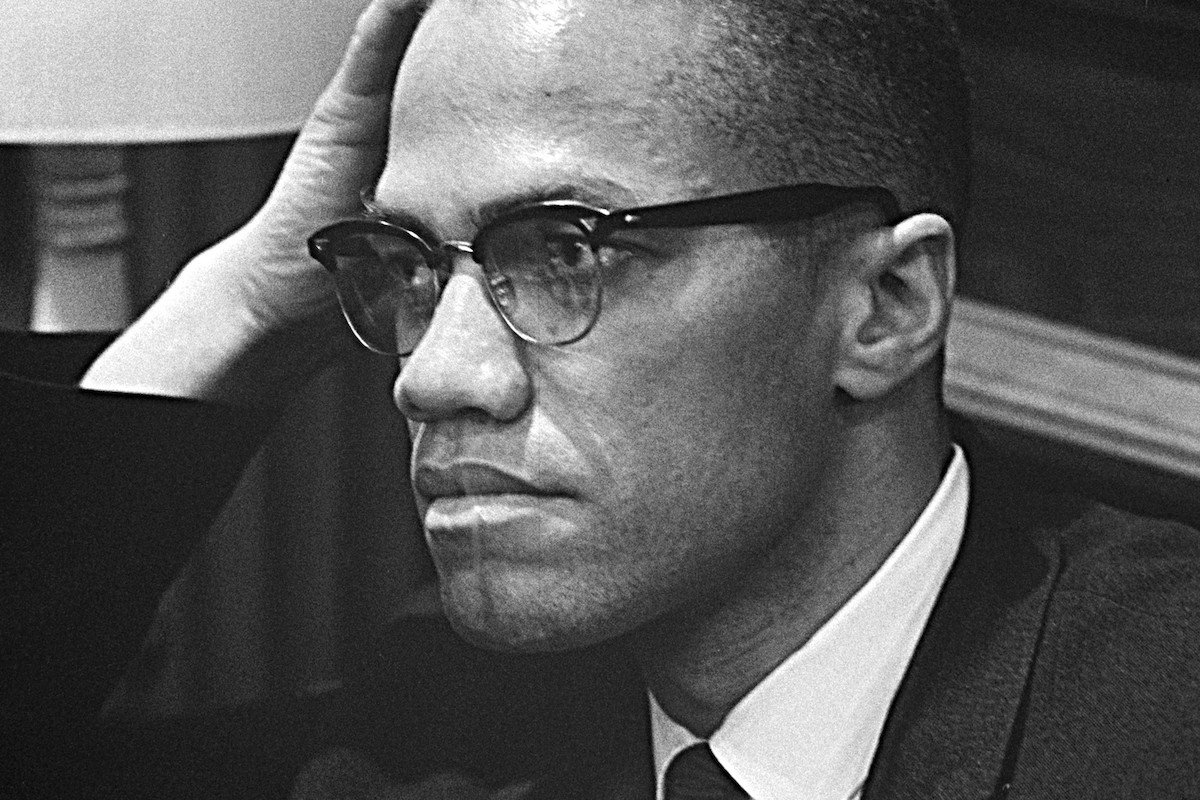

Stylized in Spike Lee’s excellent 1992 film and canonized by the thousands of high school and college instructors who have made his autobiography required reading, Malcolm X has become a man for all seasons. As a result, activists and commentators on both the Left and Right want the once-controversial figure all to themselves. To the Left, he is an icon of resistance to white political and cultural hegemony. To some on the Right, he stands apart from the Great Society statism that became the policy prescription of choice among the Civil Rights establishment, offering an alternative of self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and voluntary communalism. Not bad for a figure deemed, at best, divisive by respectable opinion during his lifetime.

The latest biography of Malcolm X will serve boosters of either narrative. In The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X, the late Les Payne shows his subject to have been a complex intellectual figure whose life, words, and actions serve a wide range of political discourses. In doing so, Payne has made a significant contribution to the popular understanding of one of the 20th century’s most significant and most widely appropriated cultural and religious figures. Payne was a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and editor at Newsday, and his mildly hagiographic biography was a labor of love completed over 28 years. Following his death in 2018, his daughter Tamara, who served as his researcher for the duration of the project, oversaw the completion of the book. The result offers a compelling and nuanced portrait of the man born Malcolm Little, who became the face and voice of uncompromising black nationalism in the 1960s.

Payne’s interest in writing a biography of Malcolm X was sparked in the early 1990s when he met the subject’s brothers, Wilfred and Philbert Little. The author’s interviews with these two men figure prominently in one of the book’s standout sections—his depiction of Malcolm’s childhood. The intimate details of the Little family provided by Wilfred and Philbert help to flesh out previous, more impressionistic renderings of Malcolm’s early life, in particular the portrait of his childhood in Michigan that appears in The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The Littles had a hardscrabble existence punctuated by hand-to-mouth poverty, regular encounters with violent white racism, efforts to raise crops in Michigan’s often frozen soil, and squabbles with kin. The violent death of their father Earl when Malcolm was only six years old further compromised the world his parents had tried to build. He was killed in a 1931 streetcar accident, which may well have been arranged by the Black Legion, a Ku Klux Klan-offshoot group in Michigan. Seven years later, his mother Louise was committed to a state hospital after she suffered a nervous breakdown.

Both parents instilled a keen sense of self-worth and racial pride in their children to help prepare them for the harshness of the world. They drilled them in the black separatist and Pan-Africanist teachings of Marcus Garvey and the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). These Garveyite teachings foreshadowed the emergence of black political and economic independence as central themes in Malcolm X’s political and social thought. Time and again, in keeping with the principles of the UNIA, the Littles refused government assistance. When the family finally accepted it in the aftermath of Earl’s death, they did not take kindly to the prying eyes of intrusive social workers. This played no small part in cementing Malcolm’s lifelong enmity toward do-gooders and bureaucrats. Even after his very public break with the racially separatist Nation of Islam (NOI) in 1964, he continued to favor black self-reliance and what Payne calls the “noninvolvement of the Black Muslims in broader societal changes.”

The Dead are Arising offers similarly interesting insights into Malcolm X’s adolescence and adult life. In unprecedented detail, Payne explores Malcolm’s youth as a street criminal in Lansing, where he was selling marijuana before he was even a teenager. While hustling in his hometown, he earned the nickname “East Lansing Red,” a precursor to the “Detroit Red” moniker he adopted in Boston and New York. It was while he was serving time in Charlestown State Prison for larceny that Malcolm Little was politically and religiously radicalized by the Nation of Islam and changed his name to Malcom X. Payne’s depiction of the NOI is particularly interesting. I was previously unaware of the degree to which Malcolm’s siblings—including recent converts Wilfred and Philbert—encouraged their brother to join the organization. Its conception of itself as a “nation within a nation” certainly jibed with the Garveyite teachings of Earl Little. For readers interested in a concise description of the spiritual foundations and cultural ideas of Elijah Muhammad and his followers, the chapter entitled “Birth of the Nation of Islam” offers an excellent primer.

The speed with which Malcolm X rose from zealous convert to a leading figure within the NOI is remarkable. During the 1950s, he began establishing a number of new temples, and within a few years, his charisma, intellect, and leadership skills had helped turn them into thriving communities. As a native of Hartford, Connecticut, Payne describes the community Malcolm X established there with particular care. The temple built in the city’s North End, Payne writes, was a model NOI beachhead made possible by its distance from the big city distractions the organization faced in places like Philadelphia and New York. Working within the cramped, predominately African American section of the city, Malcolm X built a tight, disciplined community, the details of which read like a recruitment pamphlet for the organization. He and his subordinates created a monastic environment in which members kept an eye on the lifestyles of other members, both male and female. The organization’s puritanical anti-drinking and anti-smoking dictates were firmly upheld as well as its strict dietary laws. Male recruits lived in communal apartments leased by the temple. Marriages within the community seemed to have been nearly arranged.

While Malcolm X always gave credit for his success to the leadership and guidance of Elijah Muhammad, it was clear by the end of the 1950s that the pupil was now outshining the teacher. By the mid-50s, Malcolm X had emerged as the face of the organization and was serving as the NOI’s national spokesman. As the Eisenhower era came to a close, a rift had developed between the two, as the temples under Malcolm X’s influence on the East Coast had grown much more quickly than those in Elijah Muhammad’s Midwestern power base. Covert work by federal law enforcement inside the NOI—part of the FBI’s broader COINTELPRO project against domestic political militants—exaggerated divisions between the leaders, and Payne asserts that the FBI was well aware of the plot inside the NOI that led to the assassination of Malcolm X less than a year after he left the organization.

Payne also reveals the details of a previously obscure 1961 meeting between Malcolm X and members of the Ku Klux Klan at the Atlanta home of southern NOI leader Jeremiah X. A Western Union telegram from the Georgia branch of the white terrorist organization asked Malcolm X for an audience to discuss their common goals of racial separatism. Leaders in the NOI hoped the gathering would lead to some kind of a public debate with leaders from the Klan. Instead, the gathering resulted in predictable posturing by both legations and a meandering discussion of the terms for some future fantastical settlement between the organizations for a division of the United States into black and white regions. W.C. Fellows, the leader of the Klan’s contingent, tried to turn the conversation to anti-Semitism but got nowhere with Malcolm X and his aides. Anti-Semitism became a preoccupation of the latter day Nation of Islam under Louis Farrakhan but this was certainly not the case with Malcolm X’s cadre in the early 1960s.

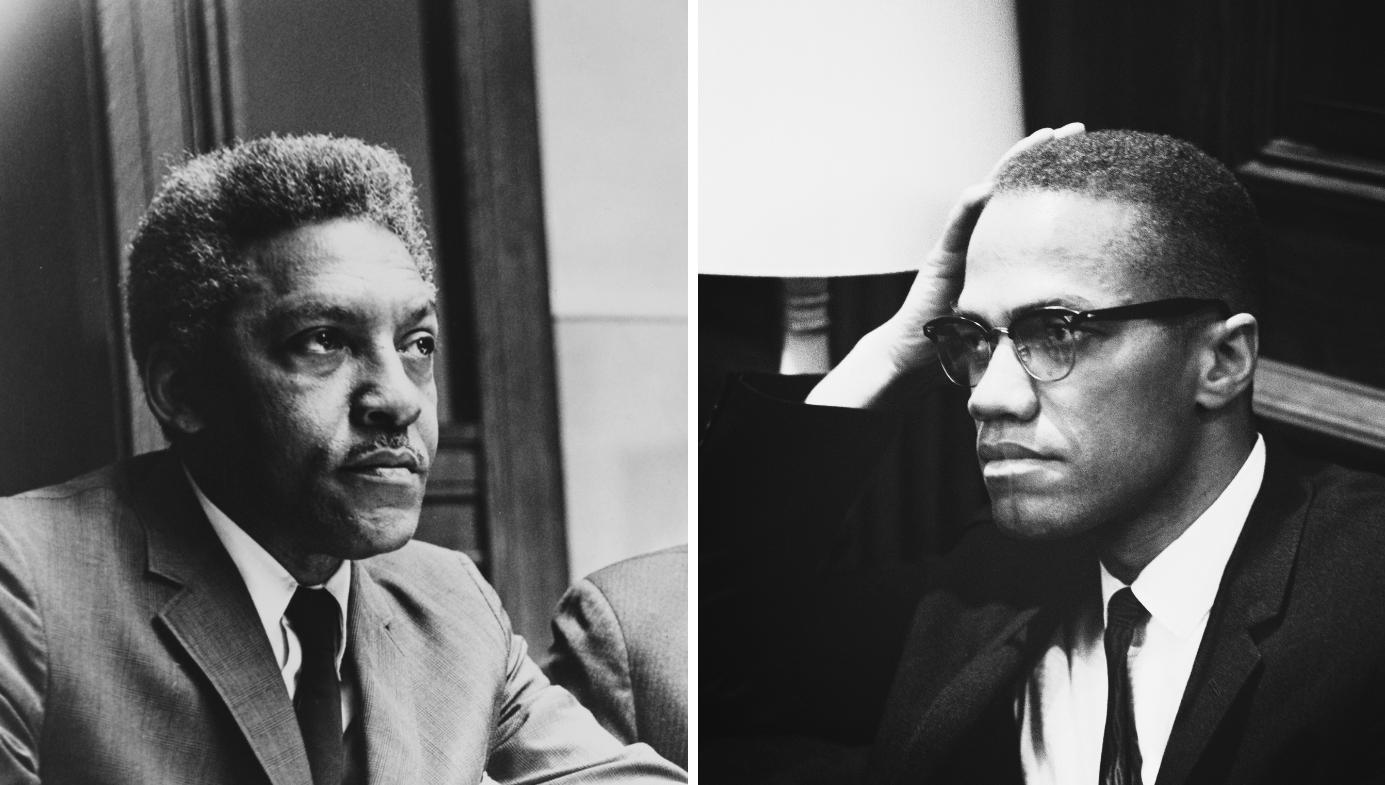

The discussion eventually converged on a common foe—Martin Luther King Jr. Representatives of the Klan tried to lure the NOI’s envoys into bringing the martial arts trained “goon squads” of the Fruit of Islam security force into a joint conspiracy to assassinate King. Malcolm X, despite his strong differences with King, refused to even consider participating in violence against another black man. The meeting soon came to an end but proved to be the beginning of a cordial relationship between the leadership of the Nation of Islam and the Klan, which Payne asserts helped to initiate Malcolm X’s break with the organization and, eventually, set in motion the conspiracy that brought his life to an end in 1965.

Despite the new insights that Payne’s biography offers into the young Malcolm Little, this book is never gossipy in the manner of Manning Marable’s 2011 Malcolm X biography. Whether discussing Malcolm X’s upbringing, his young adulthood, or his career as a religious leader, Payne maintains his professional distance and never aims to titillate. He shows scant interest in Malcolm X’s personal life once his subject becomes a public figure—Malcolm X’s wife Betty Shabazz is mentioned just a handful of times in the book, and his children are discussed even less frequently. Nevertheless, Payne’s biography ought to become the first book that readers consult on the religious leader after his classic autobiography. It is the most thorough intellectual biography of Malcolm X and the most historically situated account of the making of the man.