Art and Culture

Black Progress and Black Rage

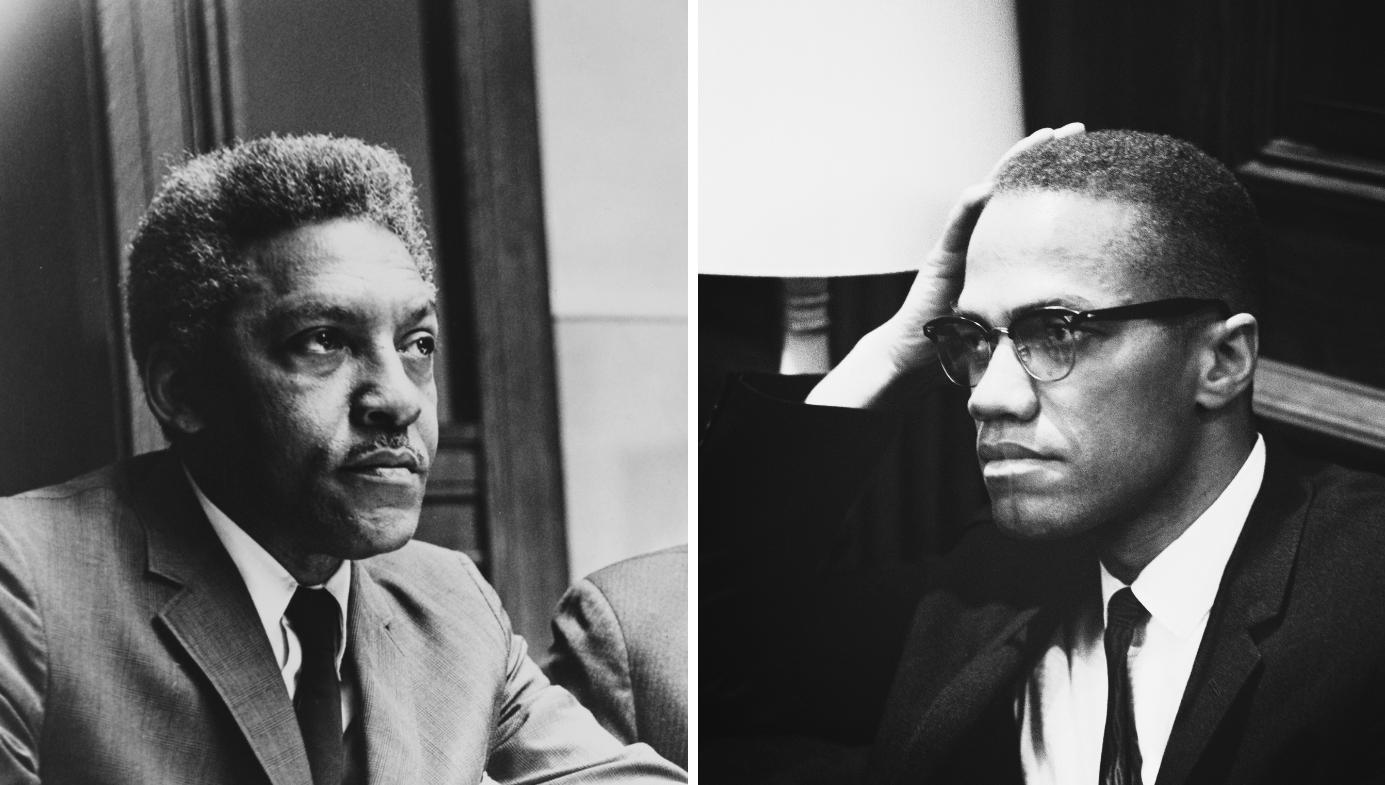

A new biopic about Bayard Rustin and the New York Met’s opera about the life of Malcolm X celebrate very different notions of black struggle.

Bayard Rustin and Malcolm X, two enormously important figures in black history, were each the subject of a major cultural event in November. The biopic Rustin, produced by Michelle and Barack Obama, opened in movie theaters and was released on Netflix. Meanwhile, New York’s Metropolitan Opera raised the curtain on X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, a decades-old production that has at last reached opera’s biggest stage.

The simultaneity is a coincidence, but the contrast between the two men brings into unusually sharp relief a fundamental divide in the struggle of black people for equality. Aside from Martin Luther King, almost no one contributed more to the victory of civil rights in America than Rustin. The only other figure who deserves to be placed ahead of him is A. Philip Randolph, who organized the first predominantly black labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters—a substantial base that enabled him to play the role of patriarch to the movement.

Randolph was also something of a father figure to Rustin, who was born to a young single mother and raised among Pennsylvania Quakers by his grandparents. The two men first collaborated in 1941, when Rustin, then in his late twenties, assisted Randolph in organizing a march to demand an executive order banning discrimination in the defense industries. President Roosevelt yielded, and the march was called off. At the war’s end, Randolph and Rustin reprised that scenario, securing an order from President Truman to integrate the armed forces.

Then, in 1947, Rustin and a few other pacificists from the Fellowship of Reconciliation undertook the first “freedom ride,” which aimed to secure enforcement of a ruling against discrimination in interstate transport. In North Carolina, he was beaten by police, arrested, and sentenced to work on a chain gang. From his cell he sent dispatches to the New York Post, generating such an outcry that North Carolina abolished chain gangs.

In 1956, the Montgomery bus boycott propelled King into national prominence. Rustin had traveled to India to study Gandhi’s techniques and he mentored King in the strategy of nonviolent protest. Then, together with Randolph and a few others, Rustin organized the first civil-rights mass marches, the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom and the 1958 Youth March for Integrated Schools. The movement gained momentum with the lunch-counter sit-ins of 1960 and the “freedom rides” of 1961, reenacting the 1947 effort of Rustin and his pacifist colleagues but this time into the murderous deep south. The gathering momentum led to the movement’s culmination in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the most important protest in US history.

The 1963 march was orchestrated by Rustin, who bore the misleading title Deputy Director (the other civil-rights leaders were afraid that his homosexuality and brief youthful membership in the Young Communist League made him too controversial to be called the Director), and it provided the venue for King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Even more importantly, it decisively tilted Washington’s political scales in favor of civil rights. There followed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, outlawing discrimination in public accommodations, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the 1968 Fair Housing Act. This trifecta of legislation put paid to a century of overt racial discrimination.

As against all this, what was Malcolm X’s contribution to the black cause? Elijah Mohammed, head of the Nation of Islam, had forbidden his followers from participating in the march, or indeed from speaking to whites at all. On the day it was held, Malcolm set himself up in the hotel where its leaders were staying and the press were swarming, and he offered soundbites deriding the march as the “Farce on Washington,” and a “a real circus.” Neither on that day nor on any other did Malcolm make any tangible contribution to black advancement.

As Rustin said over and over in a series of debates between the two, “you have no program.” In fact, the Nation of Islam did have a program of sorts: to create a separate black theocratic polity on a portion of the land mass of the United States. But they had no strategy for persuading white America to cede part of the country to them, nor, for that matter, for persuading most blacks that this presented an attractive prospect. A mark of their desperation to find such a path, Malcolm had cordial conversations with the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party about their common aim of separating the races. It goes without saying that nothing came of it.

So, what made Malcolm X a “towering figure”—as the print edition of the New York Times put it in a headline over a review of the new opera? It was his gift of articulating black rage. Two centuries of slavery followed by a century of Jim Crow, lynchings, white-on-black pogrom-like “race riots,” and more certainly gave plenty of righteous force to that rage. Expressing it in flamboyant terms, which was Malcolm’s forte, resonated in the street, as Rustin hastened to admit when the two squared off. It offered psychic rewards but no concrete progress. The same can be said about other black formations that followed Malcolm’s trail: the Black Panthers and the whole “black power” movement.

Harder to understand, much less to justify, is the enchantment that black rage holds for whites, whether out of their own guilt, a desire to feel more enlightened than other whites, or their envy of the manly grit they perceive in black survival. The US Postal Service issued a Malcom X stamp in 1999. In 2005, Columbia University created a memorial and educational center, dedicated to Malcom X and his wife, Dr. Betty Shabazz. According to the black-owned Washington Informer, dozens of streets across the US have been renamed after Malcolm, as have dozens of public schools, according to the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation, not to mention parks, a library, and so on. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, co-authored by the notoriously unreliable writer Alex Haley, has graced reading lists in countless high schools and college courses since its publication in 1965.

As for Rustin, there are just a few things named for him. The press notes for Rustin say, “He made history, and in turn, he was forgotten.” Neither the collection of his essays, Time on Two Crosses, nor the definitive biography by John D’Emilio can be found on many school lists. However, the 21st century has seen a rediscovery of Rustin and his work, and the release of an excellent documentary titled Brother Outsider.

A lot of this attention owes to the very fact that had forced him remain in the shadows of the civil-rights movement: his homosexuality has made him an avatar of “intersectionality.” As the White House put it in 2013, when President Obama bestowed the Medal of Freedom on Rustin posthumously: “Rustin stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights.” Perhaps so, but while Rustin was uncommonly at ease with his sexual orientation, he was involved in gay causes only marginally, and this work pales beside his monumental contribution to black civil rights.

However, Rustin has also been neglected because he had no interest in expressions of rage. He was arrested nearly 20 times and counted almost as many occasions on which he was beaten for his civil-rights activism, but he always kept his focus on the goal rather than whatever anger he felt. The essence of that goal as King famously put it at Rustin’s march, was that no one be judged by the color of their skin. For this reason, he rejected reverse discrimination.

One of the earliest applications of remedial racial preferences was President Nixon’s “Philadelphia Plan,” which required racial quotas in hiring for federal construction projects, thereby shredding union control. Nixon was happy to pit blacks and labor unions—two Democratic Party pillars—against one another. But Rustin believed in a coalition with labor, even though many building trades unions had practiced flagrant discrimination. Addressing the AFL-CIO in convention, Rustin denounced Nixon’s stratagem—“blacks don’t want to be ‘black plumbers’; they want to be plumbers”—while demanding that the building trades purge themselves of racist practices. And he helped to make that happen by co-sponsoring a program that recruited and prepared young blacks for the apprenticeships that were the main avenue into those trades.

When the first demands for “reparations” were raised, Rustin called it “a ridiculous idea,” adding, “If my great-grandfather picked cotton for fifty years, then he may deserve some money, but he’s dead and gone and nobody owes me anything.” Rather, he said, blacks wanted good jobs, and he advocated social-democratic programs to create them. This naturally brought him close to the labor unions of which he was a stalwart ally. When, in 1968, a teachers’ strike polarized New York City racially, with most blacks opposing the strike, Rustin (and Randolph) declared support for the union.

When Rustin viewed ostensibly pro-black demands as wrongheaded or self-defeating, he brought the same fearlessness to rejecting pressures for racial solidarity that he had brought to facing redneck sheriffs and racist mobs. Two generations later, the spirit of black rage lives on—not only in the street but now also in the academy in the name of critical race theory. This is essentially the idea that all whites, especially heterosexual males, bear a form of original sin that they must repent but can never expunge fully, and that they must atone for through systems of racial preferences.

Racism, we are told, remains ubiquitous and indelible, even though data and experience suggest otherwise. Just four percent of Americans approved of interracial marriage when Gallup first asked about it in 1958; today, that figure is 94 percent, with no appreciable difference between black and white responses. Surveying 80 countries, the World Values Project found that a good marker of racial attitudes is the idea of having neighbors of a different race. Among Americans, fewer than five percent said they disliked the prospect, placing the US among the ten least bigoted countries.

An updated 2020-version of the recently widely shared #WVS-based #racial #tolerance map. #Data source: @WVS_Survey #WVS #WorldValuesSurvey & @evs_values #EVS. pic.twitter.com/mlnYSXh5WZ

— World Values Survey (@WVS_Survey) June 29, 2020

If racism grows ever harder to find in America, critical-race scholars have discovered implicit racism, structural racism, institutional racism, and so on. As a result, survey respondents affirm the existence of racism in much higher numbers than report having recently experienced it themselves. And while members of all racial groups express satisfaction with their own lives in high and roughly equal proportion, they also say that racial relations are getting worse. So, even though Rustin’s march succeeded in breaking down structural barriers, thanks to the legacy of Malcolm X and the other apostles of black rage, we are growing ever farther from the fulfillment of King’s dream.