Cinema

So Here's to You, Buck Henry

Most of us are distant spectators to the roped-off paintings that line the museums inside our aesthetic imaginations. Some of the pieces have been removed; others don’t have appropriate labels.

I am somewhat ashamed to admit that I did not know who Buck Henry was. On the evening of his death on January 8, 2020, I had to Google his name (which sounds vaguely like the musky fragrance of an aging leather briefcase discolored by cigarette ash). According to his many admirers, Henry was the first writer to fashionize wearing a floppy baseball hat over round tortoiseshell spectacles. This is probably not true, but the residue of his mythology appears in the uniform of every New Yorker who writes about comedy; from David Letterman’s casual streetwear to the SNL writer taking their dog for a morning stroll in Central Park. You can still see this look in urban coffeehouses, where writers in colorful New Balance sneakers scribble jokes into moleskin notebooks.

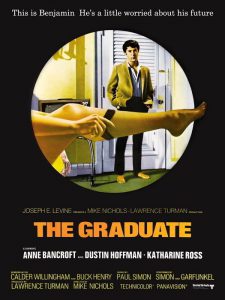

It’s almost certain that these twenty-something Buck Henry facsimiles associate the name with a woodsy-scented organic soap or fashionable strain of weed, or a dead Negro League ball player. I am not making fun of them. I am one of them. And they, like me, don’t immediately associate the name with the faded Polaroid of a writer who wrote the Oscar-winning screenplay for Mike Nichols’s iconic 1967 film, The Graduate, and who will no doubt reappear in the schlocky In Memoriam montage during this year’s Oscars. Buck Henry is what happens when you study the biography of your taste and realize it needs to be annotated. Not as some hoary newspaper obituary, but as part of a process of restoration and relabeling. Because although I was unfamiliar with his name, I was not unfamiliar with Henry’s work.

At a very young age, I would watch old syndicated episodes of Saturday Night Live on Nick at Nite, from when it was still just two-chords and a few dirty punchlines—the “Not Ready for Prime Time Players” SNL, when clown prince of chaos John Belushi was their Darby Crash. Buck Henry would host ten of SNL’s punkest rough drafts, and I remember wondering why they had invited a computer repairman with a bandaged forehead to front the show. He was the less interesting substitute teacher for Steve Martin. A talk show host I had never heard of. The child molester across the street who would invite me over to play Sega Genesis. At the age of seven, I did not yet understand the role of a “straight man” in comedy, and while there may have been others, Henry played the innocuous and sexually uncomfortable WASP so magnificently that he made John Belushi’s bushy Samurai seem even more provocative and feral.

Buck Henry was catching fast balls for wild thing John Belushi the way David Spade caught them for Chris Farley. Every exploding drummer needs a bass player to catch their shrapnel. Every John Bonham needs a John Paul Jones. Coincidentally, Henry wrote the screenplay for The Graduate inside a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont, where John Belushi would later die of a speedball overdose on March 5, 1982 inside bungalow three—not far from the lobby through which John Bonham drove his rumbling Harley. John Belushi didn’t need a “straight man” to slice with the edge of his samurai sword (Buck Henry wore a bandage for a reason); he needed someone to get him to go straight edge.

In the late-Seventies, Henry provided talent enhancement for the comic gods. When he died and went off to “make God laugh,” a phantasmagoria of images zapped across my antique TV and began to illuminate him. I discovered that he had co-written the 007 spoof Get Smart (1965–1970), which I not only watched on Nick at Nite, but incorporated into my wardrobe: Air Jordan basketball sneakers were held up to my ear as a more modernist take on Maxwell Smart’s shoe phone. The show was my first introduction to the concept of political satire, but since it was a Mel Brooks production, it was Brooks’s name with which it became associated in my mind, not Henry’s.

Inspector Gadget was voiced by Don Adams, who played Maxwell Smart on Get Smart. I used to watch Inspector Gadget on Nickelodeon without realizing that it was a parody of Get Smart—a parody of a parody. This too was revealed to me the day Buck Henry died. Buck Henry was my first “straight man,” but I did not know his sexual orientation. He was my first taste of political satire, but I did not know he was the satirist. He infiltrated my aesthetic imagination, but I had never heard of him.

The Graduate was Buck Henry’s second feature screenplay, and it revealed an ear attuned to the moment. In one of the film’s many celebrated scenes, Henry described an “eerily lit” California swimming pool besides which career advice is dispensed to the disenchanted college graduate of the film’s title. It included a single word that would touch America’s youth like the lyric from a rock song: “Plastics.”

Ben: Exactly how do you mean?

Mr. McGuire: There is a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?

Ben: Yes, I will.

That dialogue does not appear in Charles Webb’s novel. It was Buck Henry’s way of communicating the frustration of one generation to another. Even as he spoke to my millennial generation through VHS tapes and DVDs, many of us did not know his name. “Buck,” to me, is associated with hunting, buckaroos, pulp comics, space adventures, loggers, slang for the U.S. dollar, and blondish cowboys. Like “Woody,” it is an unusually masculine name for a Jewish boy who attended private schools in New York. After country singer Buck Owens, he was probably the second most famous American named Buck, even though his real name was Henry Zuckerman.

The Graduate reached across continents as well as generations. My mother and her sister first watched it in a dark cinema on a sunny day in Tehran, circa 1969. Until then, the Italian neorealist cinema of Rossellini, Fellini, Visconti, and De Sica had provided Persians with a glimpse of their own struggles—the familiar-looking ruins and bombastic personalities etched into Mediterranean faces; the refusal to lose one’s sense of style in the face of pulverizing poverty; a simple story about a stolen bicycle. Familiar faces like those of Marcello Mastroianni, who looked like a young Iranian playboy, and Sophia Loren, who was the Persian ideal of voluptuous beauty: long lashes, full Revlon lips, arched monarchical eyebrows, and naturally baked skin that turned a dangling piece of jewelry into a celestial object.

Hollywood, on the other hand, was aesthetically foreign in the eyes of Middle Eastern youth. Its blonde vapidity and phony car-commercial adventurism made the people of the Middle East feel like they were watching films cosponsored by the U.S. State Department. Occasionally, they were; Hollywood’s studio system was uncomfortably plastic for warmblooded people who saw themselves in the faces of Italian, Jewish, and Indian actors. Who were all these giggling blonde housewives and alcoholic ex-G.I.s who drove Chevrolets? Iranians knew who Rock Hudson and Doris Day were, but they appeared to be flirty mannequins of American mall culture—not real people. They wanted more than a pitch to invest in the “American Dream.”

Buck Henry’s mischievous contrarianism offered a break with all that—a snot rocket launched in the direction of films like Frank De Vol’s 1959 romantic comedy Pillow Talk, along with the dated chauvinism of characters like James Bond (whom Buck Henry and Mel Brooks would send up in the vain and imbecilic figure of Maxwell Smart). Although The Graduate was highly stylized by director Mike Nichols, and clearly indebted to the French New Wave then electrifying America’s next generation of film-makers, in its own peculiar way it was also a work of American neorealism.

My mother recalls that The Graduate was one of the first American films in which the lead looked like someone she had gone to school with. Henry rewrote Benjamin Braddock, the bleached hunk in Charles Webb’s novel, as an awkward and diminutive Jew with thick coal-black hair who would shake, not stir the archetype of a leading man. Casting Dustin Hoffman instead of a sun-soaked WASP like Robert Redford meant that Braddock’s voice needed to be de-anglicized. And he needed flaws. So Henry wrote the notes Dustin Hoffman amplified for a disenchanted baby boomer generation that yearned for a more morally ambivalent kind of American hero. “I think it was a film made by and for a generation that hadn’t had films made for it,” Buck Henry told Cineaste in 2001.

My mother was also struck that, beyond its subversive attitude towards church, family, and authority, the film lacked any noticeable activism or moralistic political agenda. She was a teenage song lyricist living in Iran, bombarded with propaganda from monarchists, student revolutionaries, Islamic fundamentalists, and communists. She wanted purity, not polemic and The Graduate’s lack of produced righteousness was seductive. Had it been written in the voice of a neurotic hippie, she might have tuned out. But Buck Henry was evidently uninterested in using his typewriter as a copy machine for the sunflower pamphleteers who were, by the time he wrote The Graduate, a bunch of wide-eyed drifters who played their music too loud. Henry was 35 when he wrote The Graduate. He did not want to please a generation to which he didn’t belong, and this made him the era’s screenwriting equivalent of a rebel without a cause; guilty even of complicity, according to Jacob R. Brackman who rebuked the film’s silence on Vietnam. It is true that the film wasn’t a fashionable protest about American foreign policy. But that is also why it was not a prisoner of its time.

I first saw The Graduate in 1999, during my Psychology class in high school. I did not know that my mother had also seen the film when she was a teenager 30 years earlier. Even in the ‘90s, watching The Graduate was a taboo experience for high schoolers just beginning to wrestle with their sexuality and desires. The teenage fantasy of being seduced by your teacher was a chapter in every pizza-stained teenage journal. Buck Henry was the writer who would adapt the character of Mrs. Robinson into an old-money femme fatale with the gimlet-eyed gaze of a predator—a dangerous woman whose manicured fingernails were like sharpened claws and whose leopard-print underwear radiated excitement as well as danger.

Buck Henry, I’ve since discovered, was the son of blonde silent-era starlet Ruth Taylor, who appeared in Malcolm St. Clair’s 1928 adaptation of Anita Loos’s novel, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Taylor was handpicked by Loos to play diamond-eyed hedonist, Lorelei Lee. In 1927, Paramount Pictures would distribute thousands of glamorous photos of Taylor to announce her casting as the ultra-modern face of young Hollywood. In 1949, Loos would say that Taylor was “so ideal for the role that she even played it off-screen and married a wealthy broker.” In 1930, Taylor married New York stockbroker Paul Steinberg Zuckerman and became a “Park Avenue socialite.” Then the stock market crashed. Buck Henry was born in New York City on December 9, 1930 while the Great Depression was in full swing.

The more famous Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell remake of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes directed by Howard Hawks appeared in 1953, when Buck Henry was 23. For reasons that remain unclear, the 1928 version of the film is as lost as Taylor’s biography is obscure. Nevertheless, Mrs. Robinson (played by Anne Bancroft) seems to be informed by the kind of retired fur-draped flappers, alcoholic housewives, and retired silent-era actresses who would visit Henry’s mother—the louche and laconic seductress in thick Italian-looking mascara, who devoured cigarettes like a mobster’s wife, or what Anita Loos may have described as a trashy Park Avenue socialite. It is almost unfathomable to think that a rouged sugar-cube like Doris Day was considered for the part. Bancroft was initially hesitant to accept such a lurid role, but was thankfully persuaded to do so by her husband, Mel Brooks. She was my first introduction to the erotic and stylish cigarette-smoking medusa that would become my cinematic fetish for the next three decades.

Most of us are distant spectators to the roped-off paintings that line the museums inside our aesthetic imaginations. Some of the pieces have been removed; others don’t have appropriate labels. Although we wear our influences on our sleeves, sometimes we don’t even know why we like the things we like or where they came from—we just allow the cultural wave to wash over us. It’s easier that way. But what happens when you are confronted with one of the uncredited ghostwriters who helped curate your aesthetic? Do you have an Art Garfunkel buried in the timeline of your taste? Buck Henry was mine, and in death, he revealed himself as the composer of a silent symphony I had been listening to my entire life.