Books

The Million-Petalled Flower

He had the gift of producing them by inverting or adapting cliché to give it new life.

“Who wrote this? “Political language—and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists—is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” But you guessed straight away: George Orwell. The subject stated up front, the sudden acceleration from the scope-widening parenthesis into the piercing argument that follows, the way the obvious opposition between “lies” and “truthful” leads into the shockingly abrupt coupling of “murder” and “respectable,” the elegant, reverse-written coda clinched with dirt-common epithet, the whole easy-seeming poise and compact drive of it, a worldview compressed to the size of a motto from a fortune cookie, demanding to be read out and sayable in a single breath—it’s the Orwell style. But you can’t call it Orwellian, because that means Big Brother, Newspeak, the Ministry of Love, Room 101, the Lubyanka, Vorkuta, the NKVD, the MVD, the KGB, KZ Dachau, KZ Buchenwald, the Reichsschrifttumskammer, Gestapo HQ in the Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse, Arbeit macht frei, Giovinezza, Je suis partout, the compound at Drancy, the Kempei Tai, Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom, The Red Detachment of Women, the Stasi, the Securitate, the cro-mangon Latino death squad goons decked out in Ray-bans after dark, that Khmer Rouge torture factory whose inmates were forbidden to scream, Idi Amin’s Committee of Instant Happiness or whatever his secret police were called, and any other totalitarian obscenity that has ever reared its head or ever will.

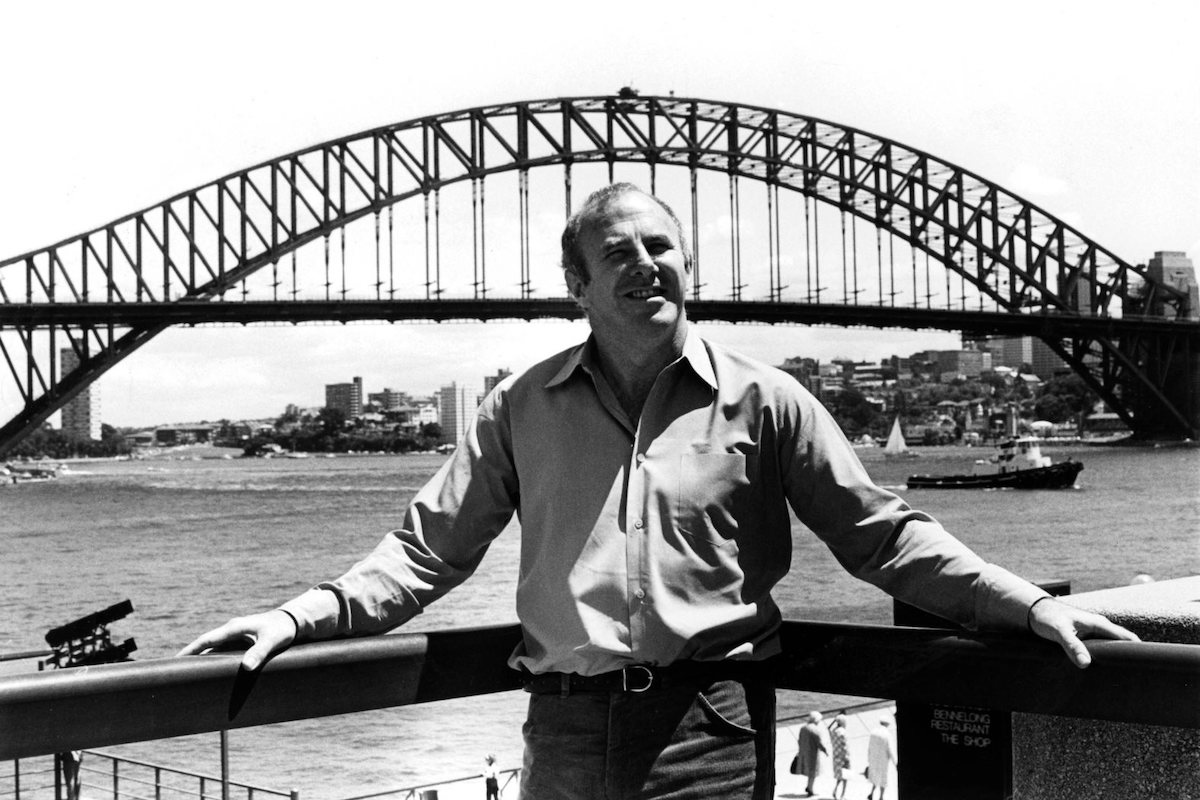

So who wrote that? If you have ever read him at all then there is a good chance you “guessed straight away”: Clive James, the brilliant Australian polymath who died last month aged 80. There is the minute observation of language, the lavish yet breezy and jocular wit—he once described his style as “a cabaret act”—informed by lightly-worn erudition, the seemingly careless indifference to trivial matters (“or whatever his secret police were called”) that rested on a sound sense of priorities, and his own form of acceleration, nearly to exhaustion as he lists the totalitarian horrors. Indeed, he hurtles towards an appropriately nameless abyss.

One of his many shows on British television was titled “The Late Clive James.” Sadly, we can now use the words without punning. James’s death at his home in Cambridge has deprived Australia of arguably the greatest man (or, yes, woman!) of letters the nation has produced. At least 50 books of essays, reviews, poetry, translation, autobiography, travel-writing, song-lyrics, novels, all marked by scintillating wit, prodigious learning, and an incisive but generous humour. It is the oeuvre not just of a colonial made-good but of something approaching a renaissance man.

Which is why always seeing him through an Australian lens, while understandable if you are Australian, is too insular. Over his protests, journalists persisted in grouping him with his expatriate contemporaries, feminist Germaine Greer, comedian Barry Humphries, and art critic and historian Robert Hughes. For some this was a kind of Aussie boosterism. Others could not believe it was real. One commentator described James as a “professional Australian,” who had apparently made his way in Britain by, in James’s words, “smarming his way upwards in the capital city of imperialism by shamelessly peddling his colonial identity to con the Poms.” James wondered, in mock modesty, if it was conceited of him to expect the author to make “some attempt at assessing the way I write—if only to demonstrate how I worked the scam.” For while James was a writer from Australia, he was not especially an Australian writer, notwithstanding his deep affection for, and interest in, his native land. He did do a lot to promote gifted Australians, especially poets like Les Murray and Peter Porter. But otherwise, as a general rule, his writing shows little trace of his birth-place, bar in his autobiography, or when he chose to address Australia or an Australian matter deliberately and directly.

Most of what he wrote could have been written by someone from New York or Johannesburg—or Delhi or Buenos Aires—as readily as from Sydney. For the real intellectual from “down under” there never has been the “cultural cringe” that was once so often remarked on in Australia—and that itself was always a bit cringe-worthy. Such a person already belongs to the world, even if they, or the world, don’t already know it. James felt no unusual need to prove himself on account of his provenance when he arrived in London, penniless and without a return ticket, in the early ’60s. If there was bias for or against him on that score he brushed it off. Cynics may be unwilling to acknowledge that talent ever counts, but James’s career proves them wrong—most likely they cut down what Australians call “Tall Poppies” with chips fired from their own shoulders.

After living near-rough in London for three years, he went up to Cambridge, ostensibly to study English literature, but really to take the university by storm. As he once remarked to Stephen Fry (also a Cambridge man, and a kindred spirit) he was one of the “goof offs.” Which means formal study languished while he took control of Footlights—that nursery of so much comedic talent in the UK—became the in-house writer for several university publications, acquired some European languages, and enjoyed beer and the company of women. The love of women appears regularly in James’s work as a poignant heartache of the unfulfilled, something wistful just outside his reach. This lamentation is representative:

… in Cambridge … [a]t the time the number of male undergraduates known to be cohabiting with females could be counted, with difficulty, on the fingers of one hand—with difficulty because the hand would be trembling with envy.

It’s too good-humoured to be the hymn of the Incel, and in fact he did all right for a man who admitted he was not a stunner in the looks department. He amply compensated with his charm and jest (his own modest way of describing this was: “I could fall in love in 10 minutes and tell her about it for ten hours”). The black and white photographs show he managed to affect a dashing young blade with a raffish ’60s persona, including the cravat, the sideburns, and the lurid psychedelic shirt.

But Cambridge (like his career at the University of Sydney before it) was merely preparation. He knew his destiny was elsewhere: the carnival barker rather than the seminar don as he once put it. His stellar extra-curricular career brought Fleet Street suitors and he threw over his doctoral thesis on Shelley for a television column in the Observer. This was a surprise hit—so much so that selections from it were republished in books like Visions Before Midnight and The Crystal Bucket, the very titles of which advertised the wit of their contents. This rapidly led to more writing invitations until, in just a few years, he reached the point where he didn’t need to write anything he didn’t want to. And inevitably his electric and semi-comic style, turbo-charged with the speed of a young man in a hurry, attracted the interest of television. The criticized courted the critic—even the column itself eventually got translated into a show. It was called Clive James on Television (get it?). Another was called Saturday Night Clive. He hosted at least nine recurrent shows through the ’80s and ’90s, and dozens of “one offs” before, during, and after that.

On television, he transitioned from the appearance of his rakish youth to a familiar uniform of maturity: the bland business suit with the tie that never quite does up properly at the neck and that at the other end droops sadly over the pot belly (discretely concealed beneath the table or below the camera shot). Still, his hefty figure, complete with wobbly parts, exhibited a peculiar grace, perhaps because he never let it faze him. As he introduced Margarita Pracatan (his camp in-house nightclub singer) or commented on footage from a crazy Japanese game show, his sense of fun transcended his physical ordinariness. Most of his popular shows followed a similar pattern—a Parkinson-style interview, or him seated at a desk like a news-reader satirising the events of the day or some other weirdness, in a format pioneered by David Frost.

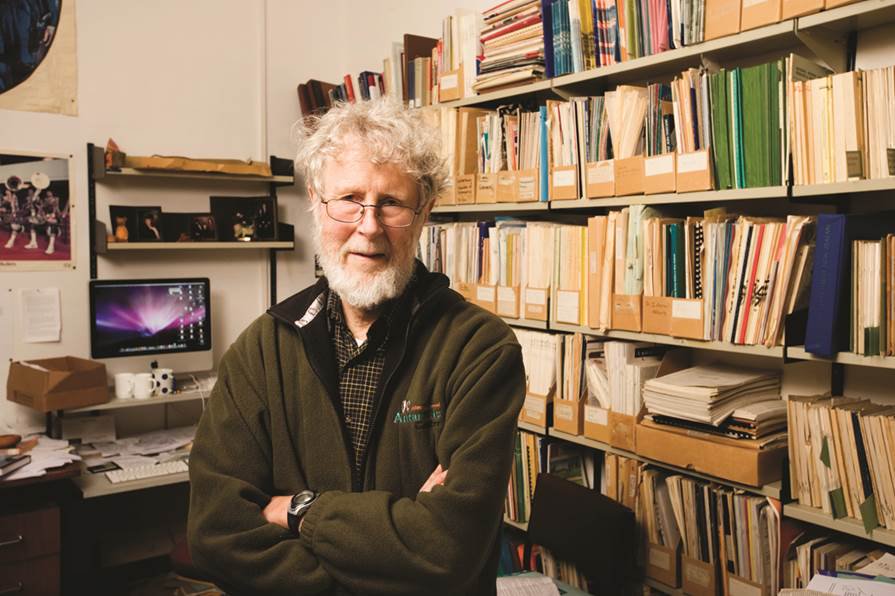

There were also the more serious programs, interviews, or discussions of politics, philosophy, and literature. One of the most striking features of James’s work was the way he moved effortlessly between the erudite and the popular with no sense of incongruity. It was all culture to him, some parts better than others, but all up for evaluation, with pleasure to be had and merit to be recognized wherever they appeared. In the same easy way, he moved back and forth between television, the press, and books. All the time James was on television, he was writing irregular but frequent pieces for the Times Literary Supplement, or the New Yorker or wherever, and collecting them into a series of books that continued at intervals for the rest of his life. The man who wrote about Star Trek and The Sopranos also wrote about Seamus Heaney and D H Lawrence, Pushkin and Primo Levi—and translated Dante’s Divine Comedy. Sometimes he wrote about both in the same piece, nay, the same sentence. The television star was also the gentleman-scholar.

James respected each medium to which he contributed, and thus each respective audience, by always trying to do his best. He angrily threw back in journalist Richard Ingrams’s face the accusation that he looked down on the radio shows he did. In the same piece he excoriated Malcolm Muggeridge who “forgives himself for doing second-rate work in the press and television by calling them second-rate media.” Perhaps he did not always live up to this ideal (not, perhaps, when signing his 500th book, in one of those ordeals through which publishers put their most successful authors). But his vision of a single culture, high-brow to low, and his commitment to taking every department of it seriously, was genuine.

His prose had a bantering, sparkling, rollicking quality. Dancing like Muhammad Ali, the punch-lines just kept coming. An example at random from his autobiography Unreliable Memoirs, remembering his grim lodgings on first arriving in London:

My new home was nondescript, in the strict sense of there being nothing to describe. Wallpaper, carpets and furniture had all been chosen so as to defeat memory. … The list of rules forbade cooking in one’s room, taking already cooked food to one’s room, or taking food that did not need cooking to one’s room. No visitors were allowed in one’s room at any time for any reason: if one died, one’s body would be allowed to decompose. Breathing was allowed as long as it made no noise. The same applied to sleep. Anyone who snored would wake up in the street. The proprietor had not made the mistake of retaining the original thick internal walls. They had been replaced by twice as many very thin ones, through which he and his lipless wife would accurately hear, and, some lodgers whisperingly warned me, see.

He had a first-class ear, even for machinery. Describing his first visit to a laundromat:

After 10 minutes of going gwersh gwersh … [t]he window in the front of the machine having whited out completely, the flap in the top popped open and a gusher of suds began gouting out, enveloping the machine and advancing inexorably across the floor. It was an albino volcano.

Most writers would trade ten years of their life for that last image. He produced examples of that quality on nearly every page. He had the gift of producing them by inverting or adapting cliché to give it new life. Apparently, after a concert in London, Frank Sinatra was struck with a projectile thrown by a disgruntled fan. Sinatra was notorious for his dislike of what was then called “the press.” The press returned the compliment. James summed it up perfectly: “The first time the fan has hit the shit.”

His writing on literature was just as brilliant. Befitting a writer who had to earn his income from paying customers, he knew that if someone bought his book, or a magazine with his article in it, he owed them something: some serious and respectful thought, and certainly some entertainment. And he usually provided both together. It did not come encumbered with the apparatus of the formal scholar, weighed down with cluttering footnotes, or the earnest impedimenta of academic jargon. Likewise, he did not tire his reader with self-pre-occupation. Even in his Memoirs quoted from above he is usually the bemused or naïve observer (or hapless victim) of the world around him, his real subject. He had opinions, but he did not make every topic an occasion to push them. He did not hector his readers. Nor did he make them a sounding-board for his spleen. As a critic he could be severe, even savage, but there was usually a serious point behind any harsh words. He knew the temptation of envy though and warned against it. He knew resentment could burn a writer up. His poem ‘The Book of My Enemy Has Been Remaindered’ poked gentle fun at the pettiness of literary quarrels. Its first stanza:

The book of my enemy has been remaindered

And I am pleased.

In vast quantities it has been remaindered.

Like a van-load of counterfeit that has been seized

And sits in piles in a police warehouse,

My enemy’s much-praised effort sits in piles

In the kind of bookshop where remaindering occurs.

Great, square stacks of rejected books and, between them, aisles

One passes down reflecting on life’s vanities,

Pausing to remember all those thoughtful reviews

Lavished to no avail upon one’s enemy’s book –

For behold, here is that book

Among these ranks and banks of duds,

These ponderous and seemingly irreducible cairns

Of complete stiffs.

The surface levity of James’s prose concealed its gravity. There was a golden thread of serious concern that ran through all his written work (not all his television, but certainly some of it). Most conspicuously, he was serious about language—its precision, its redolence, its inventiveness, its infinite beauty. He detested the lazy and shoddy use of language. He introduced one example thus:

In writing, to reach the depths of badness, it isn’t enough to be banal. One must strive for lower things.

The unfortunate victim of the subsequent shellacking was this passage, a sentence exhausted by over-use of metaphor:

Now, the onus is on Henman to come out firing at Ivanisevic, the wild card who has torn through this event on a wave of emotion.

Three metaphors there, at least. Yes, “wild card” is pretty much dead (like “onus”—look it up), but as James says:

… it was brought in from gambling for use in tennis, but we court pedantry if we ask for it to be brought alive. All we can ask for is that it not be too grotesquely transfigured in its death: the corpse should not be mutilated. If a wild card tears through something, it should not be on a wave of emotion.

Next comes the main point. He uses satire to rev the audience up, then switches register mid-stream to spell out the moral in plain terms:

Speaking as one whose flabber is hard to gast, I’m bound to say I was floored [by reading the example]. Not bound in the sense of being tied up with ropes by a burglar, or floored in the sense of having tipped my chair over while trying to reach the telephone with my teeth: I mean floored in the sense of having my wings clipped. One of my convictions about the art of composing a prose sentence in English is that for some of its potential metaphorical content to be realised, the rest must be left dormant. You can’t cash in on the possibilities of every word. In poetry you can do more of that than in prose, but even in poetry … you must concentrate your forces to fight your battles, and there is no concentrating your forces in one place without weakening them in another …

But he was no mere pedant policing grammar and style. He loved language because he loved the human mind and human freedom. He scorned the advertising hucksters and the ministerial spin doctors, the professional orators and propagandists—the modern sophists—who twist language to lie and manipulate. He despised the latter-day Robespierres and Lenins in some of our media and universities for whom free language and free thought are the enemy. But he was not obsessed with them and he did not allow them to set his agenda. His love of language was a positive celebration, a never-ending jubilation, a life-long love story. He went to what he loved and thought important, and cherished it.

This was a quiet but brave humanism. It stood out against the background of the monstrosities of the twentieth century, like those listed in the passage quoted at the beginning of this essay. In much of his work—most conspicuously in Cultural Amnesia, an encyclopaedic collection of short pieces on some of the most important figures of the twentieth century, written quite consciously to combat the vacuum pull of the memory hole—he wrote under the pressure of someone feeling we have all had a narrow escape, and that we need to remain on our guard against authoritarian, anti-human forces. The main interest is in the work and the lives of the people discussed, but there is also an eye on what lessons we may learn. The humour is still there, but the clown on the stage is also a sentinel in the watchtower.

There is a painting (in the Art Gallery of New South Wales) by his friend and fellow Australian native Jeffrey Smart in which—in a typical Smart scenario—James is a small and lonely figure, standing on a bridge, the only human being against a cold cityscape of concrete and steel, with the bottom two thirds of the canvass threateningly covered by a glaring metal fence, perhaps a kind of Berlin Wall. It is a man-made world that is disturbingly anti-human. It could be taken as an image of how James saw the writer who would dare stand against the enveloping forces of evil. How perhaps he saw some of his heroes like Orwell, or the Russian and Polish dissidents Nadezhda Mandelstam and Czesław Miłosz.

The last two were subjects in Cultural Amnesia. James knew how to pistol-whip the reader when the topic demanded it. In the Miłosz essay he wrote of the fate of a barely known young Polish writer thus:

Miłosz had seen a civilisation collapse: like any of the post-war Polish writers awarded the privilege of growing to adulthood he had been obliged to wonder whether a national culture can be said to have any roots at all after the nation itself has been obliterated. It has to be remembered that the typical Polish writer was Bruno Schulz. But for that to be remembered, Bruno Schulz has to be remembered, and the main reason he was so easily forgotten is that a Gestapo officer blew his brains out.

This sort of writing does run the risk of playing for a cheap effect, which James generally avoided. And he was capable of gentler, moving passages, like this from the essay on Mandelstam and her accounts of life and death in the Soviet Union:

… [h]er originality lies in her slowly dawning realisation that decency is a human quality which can exist independently of social origins. Without that realisation, she would never have been able to formulate the great, ringing message of her books, an unprecedented mixture of the poetic and the prophetic—the message that the truth will be born again of its own accord. She didn’t live to see it happen: so the whole idea was an act of faith. … One principle [of her writing] was that the forces of unreasoning inhumanity had won an overwhelming victory with effects more devastating than we could possibly imagine. The other principle was that reason and humanity would return. The first was an observation; the second was a guess; and it was the inconsolable bravery of the observation that make the guess into a song of love.

Perhaps the Smart painting can also be read as an image of creeping mortality, able to be postponed, but not prevented. James lived his last ten years in its slowly darkening shadow, the victim of more than one serious illness. Dr Johnson said that knowing you will be hanged in the morning concentrates the mind. One thing it concentrated James’s mind on was poetry, the genre he most prized and most aspired to. Throughout his career he had returned to it again and again, both as critic and as poet, and in his final decade he published several volumes. Most of it was new work, but it included a collection—published just this year: Somewhere Becoming Rain—of his numerous essays on Philip Larkin, one of his favourite poets. In one of these essays he quotes this passage from Larkin’s “The Old Fools”:

At death, you break up: the bits that were you

Start speeding away from each other for ever

With no one to see. Its only oblivion, true:

We had it before, but then it was going to end,

And was all the time merging with a unique endeavour

To bring to bloom the million-petalled flower

Of being here.

The penultimate line strikes me as containing a good image for James’s body of work. As an admirer of Larkin, I hope he would agree. After all, a million-petalled flower is as dazzlingly beautiful as anything could be, and he closes the essay with the thought that Larkin—“the poet of the void”—offers us:

… the possibility that when we have lost everything the problem of beauty will still remain. It’s enough.”

Andrew Gleeson is an erstwhile philosopher who learned how to read and write partly by reading Clive James. He lives in Adelaide, Australia.