Politics

Denial and Defamation—The ITN-LM Libel Trial Revisited, Part One: The Camps

The story of the ITN trip to Bosnia—and the bitter quarrel about its reporting that followed—is a cautionary tale about the destructive and deranging effects of ideological hubris.

Introduction: From Phnom Pehn to Srebrenica

In 1977, Noam Chomsky and his co-author, the late Edward S. Herman, wrote an essay for the Nation entitled “Distortions at Fourth Hand,” in which they scorned reports that the Khmer Rouge were turning Cambodia into a charnel house. Stories of genocide, they suggested, were either exaggerated or fabricated outright by refugees, and any deaths—regrettable though they may be—were most likely the result of disease, starvation, and confusion caused by America’s devastating involvement in the foregoing civil war.

The two books that bore the brunt of Herman and Chomsky’s disdain were John Barron and Anthony Paul’s Murder of a Gentle Land and François Ponchaud’s Cambodia Year Zero. Contemporaneous accounts from and about war zones are rarely correct in every particular. But Chomsky and Herman ignored everything Ponchaud and Barron-Paul got right, and seized upon isolated errors and inconsistencies to discredit their work in its entirety. Gareth Porter and George C. Hildebrand’s book Cambodia: Starvation and Revolution, on the other hand, they praised as “a carefully documented study of the destructive American impact on Cambodia and the success of the Cambodian revolutionaries in overcoming it, giving a very favourable picture of their programs and policies, based on a wide range of sources.”

Chomsky and Herman were not stupid men. In addition to being America’s most influential linguist, Noam Chomsky remains among the West’s most venerated left-wing intellectuals, while Herman (who died in 2017) was an economist and professor of finance at the University of Pennsylvania. But so powerful was their desire to condemn the United States as the preeminent source of global suffering and woe, that they misrepresented reality and worked energetically to discredit anyone who objected.

This pattern of radical genocide denial would be repeated during and after the Bosnian war in the early 1990s—not least by Herman himself1—as stories of Serbian atrocities began to emerge from the former Yugoslavia. In February 1996, seven months after the murder of nearly 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica, and just two months after the Bosnian war had finally ended, a small British magazine called Living Marxism published an essay by sociologist Frank Füredi under the pseudonym “Linda Ryan,” in which he stated that, “There is no hard evidence that 3,000, let alone 8,000, Bosnian Muslims were massacred in Srebrenica.” The United States’ interest in Serbian war crimes was, he warned, “not a noble crusade by Washington, but a self-serving attempt to occupy the moral high ground in international affairs.”

In July of the same year, Living Marxism printed an interview by a young German polemicist named Thomas Deichmann with the Austrian novelist (now Nobel laureate) Peter Handke, whose revisionist travelogue A Journey to the Rivers: Justice for Serbia had just produced an outcry. Ten years later, Handke would vindicate his critics’ worst suspicions by delivering a lachrymose eulogy at the funeral of former Serbian president and indicted war criminal Slobodan Milošević. But in 1996, Deichmann and Living Marxism’s editor Mick Hume were happy to promote his complaints about the “artificially created aggressor Serbia” and the Western media, which he described as “a kind of Fourth Reich.” Deichmann lamented the “moral vituperation” to which Handke had been subject “because he questioned the European media’s lopsided presentation of the [Bosnian] war and their demonising of the Serbs.” In an accompanying editorial entitled “The New Inquisition,” Hume praised Handke for “raising some important and insightful questions about the issues of our time,” and likewise deplored the vilification of “a reasonable man” who wished to “question the demonisation of the Serbian people.”

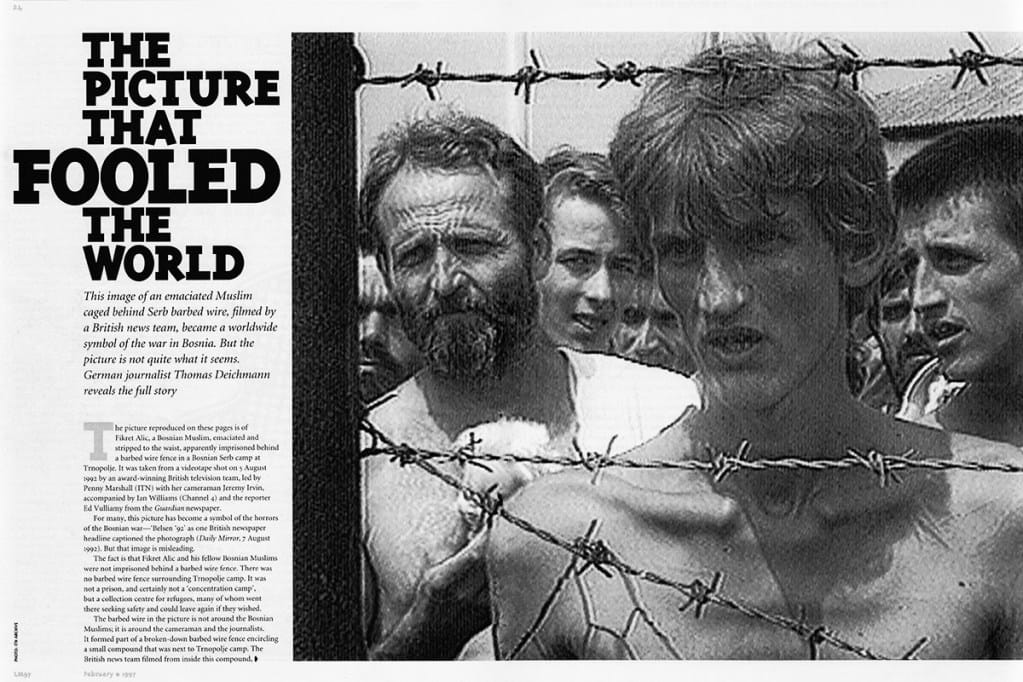

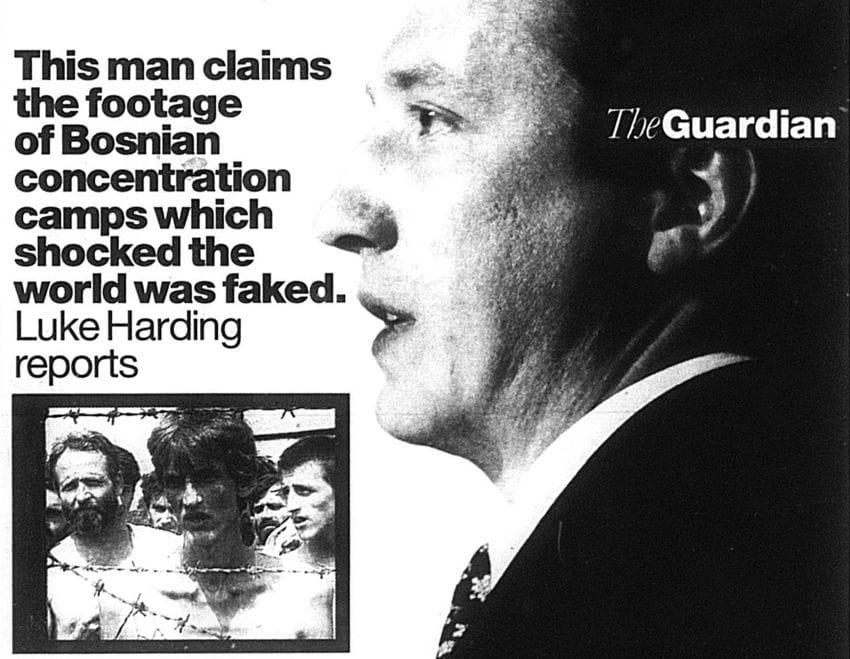

Then, in February 1997, Hume’s magazine (which had by then been rebranded as LM) published a 5,000-word cover story by Deichmann that would precipitate a media scandal. Entitled “The Picture that Fooled the World,” it accused Independent Television News (ITN) journalists of misleading viewers about the nature of two Serb-run detention camps they had visited in Bosnia in 1992. The article excited considerable interest, not least because ITN was (and is) a respected television production company with a reputation for scrupulous reporting and objectivity. ITN and its journalists sued LM in a British court, and when the case finally came to trial three years later, they were awarded swingeing damages for malicious libel, plus costs.

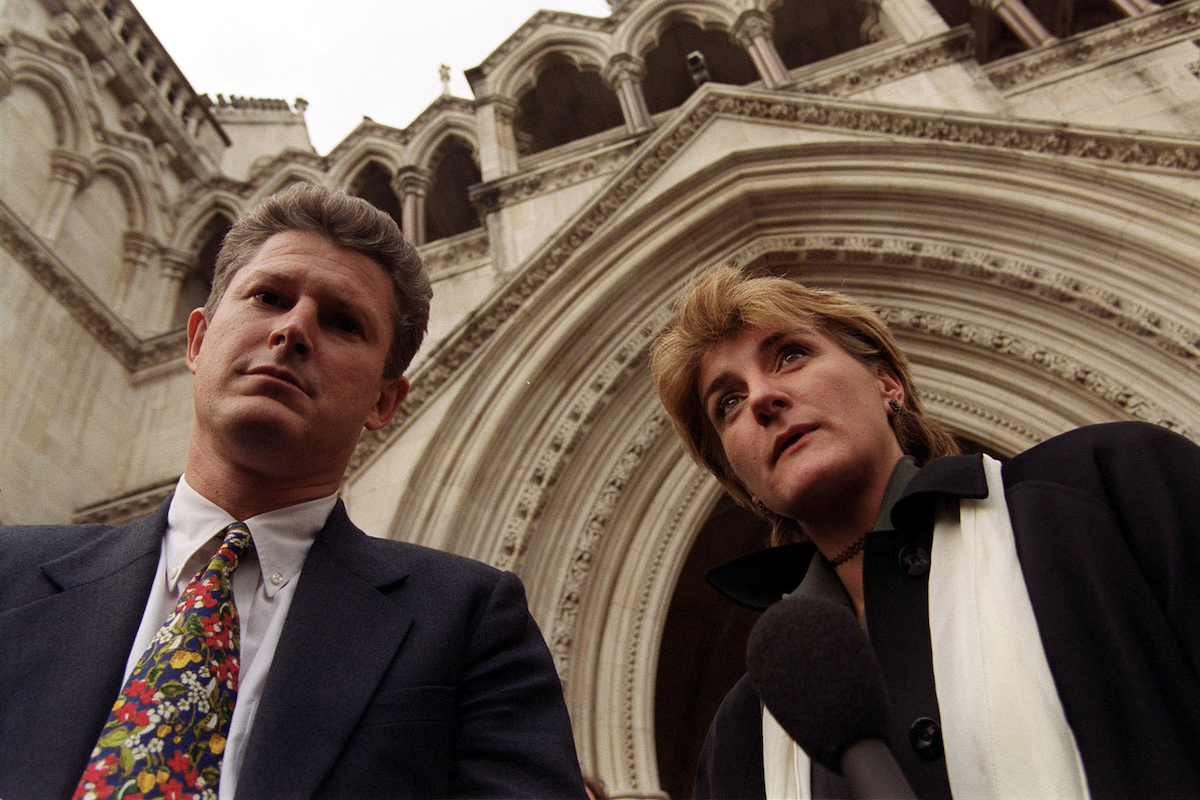

Hume, and LM’s publishers, Claire Fox and Helene Guldberg, were unrepentant. “We apologise for nothing,” Hume told the press assembled outside the High Court in London immediately after the verdict. “But we will not be appealing. Life is too short, and other issues too important, to waste any more time in the bizarre world of the libel courts.” Facing bankruptcy, Hume and Guldberg shuttered their magazine and immediately relaunched it as Spiked-Online, while Fox became founding co-director of the Academy of Ideas, an LM-associated think-tank initiated before the magazine folded, which continues to operate under Fox’s sole directorship today.

More than nineteen years after their humiliation in court, Hume and his supporters continue to insist that the verdict was a travesty and that LM was punished for speaking uncomfortable truths to power. Having clung to a revisionist account of the Bosnian war which destroyed their magazine, they went on to develop a revisionist account of the libel trial itself, according to which a tiny independent magazine embarrassed a large news corporation, and was then crushed by a vindictive court and the monstrous injustice of Britain’s libel laws.

None of that is true. And the truth of this now-obscure episode matters, because the trial turned on a point of recent history that a committed ideological fringe remains determined to disfigure. As I was completing this essay, news that Peter Handke had been awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for Literature was greeted with widespread revulsion, and briefly brought the history of the Bosnian genocide and those who misrepresented it back onto the front pages of the international press. It should not be forgotten that Living Marxism also spent eight years putting their shoulder to the revisionist wheel. And those who continue to protest the trial’s outcome invariably do so as part of an implicit—and frequently explicit—attempt to invalidate the reckoning with Living Marxism’s record of defamation and denial that the trial was intended to provide.

But, besides the need to provide a detailed correction of the record, there is an additional reason to revisit this episode. At a time of resurgent conspiracism and nationalist populism, the story of the ITN trip to Bosnia, the sensational reports its reporters filed, and the bitter quarrel that erupted five years later, offers a cautionary tale about the destructive and deranging effects of ideological hubris. And it all began with an impulsive offer made by the leader of the Bosnian Serbs during a visit to London in the Summer of 1992.

I. The Invitation

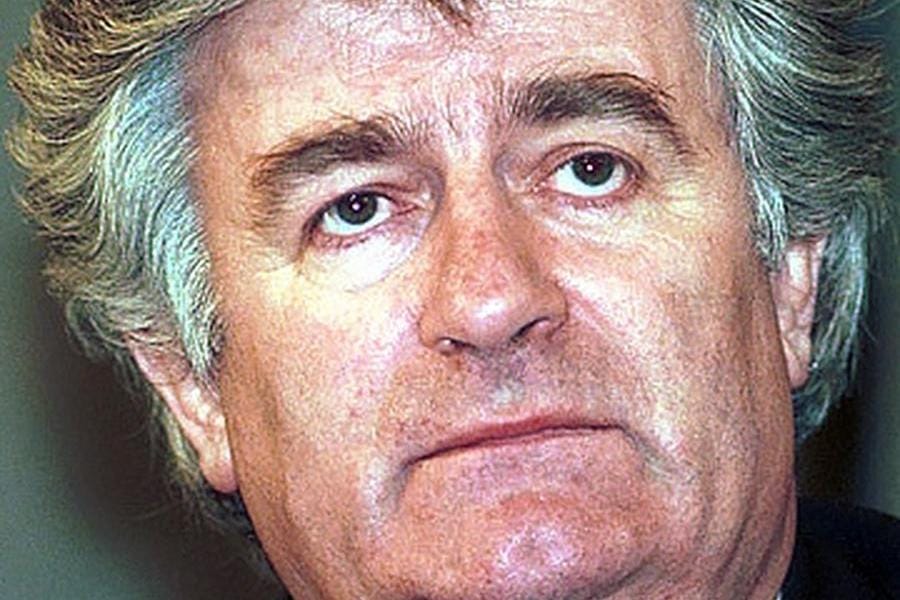

The disintegration of the former Yugoslavia into its constituent ethnic parts started in June 1991 with the secession of Slovenia, followed by a nasty war between Serbia and Croatia that would be temporarily halted in January 1992. Bosnia-Herzegovina, an ethnically mixed region containing Serb, Croat, and Muslim populations, declared independence from the rump of Yugoslavia on March 3rd, and the new polity was granted diplomatic recognition by the United States and the European Community (EC) on 6 April. The Bosnian Serbs, who had boycotted Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence referendum and were determined to remain part of a Greater Serbia, established an autonomous Serbian republic within Bosnia, led by a former poet and psychiatrist named Radovan Karadžić. Serbian forces then besieged the Bosnian capital Sarajevo, and the ugliest and most murderous of the Balkan wars erupted.

On the night of 29 April, the Serb leadership in the Prijedor municipality in northwest Bosnia staged a bloodless coup d’état. The Serbian military then began conquering the towns, villages, and hamlets in the Prijedor region and emptying them of non-Serbs—a systematic campaign of murder, terror, property destruction, and mass expulsion and incarceration now known as “ethnic cleansing.” Disturbing rumours began to circulate of an archipelago of prison camps, established by the Serbs to hold the vast numbers of people driven from their homes by the Serbian army’s relentless advance. On 19 July, American journalist Roy Gutman filed a dispatch for Newsday from a camp on mount Manjača in Northern Bosnia, which he described as:

One of a string of new detention facilities which an American Embassy official in Belgrade, the Serbian capital, routinely refers to as concentration camps. It is another example of the human rights abuses now exploding to a dimension unseen in Europe since the Nazi Third Reich.2

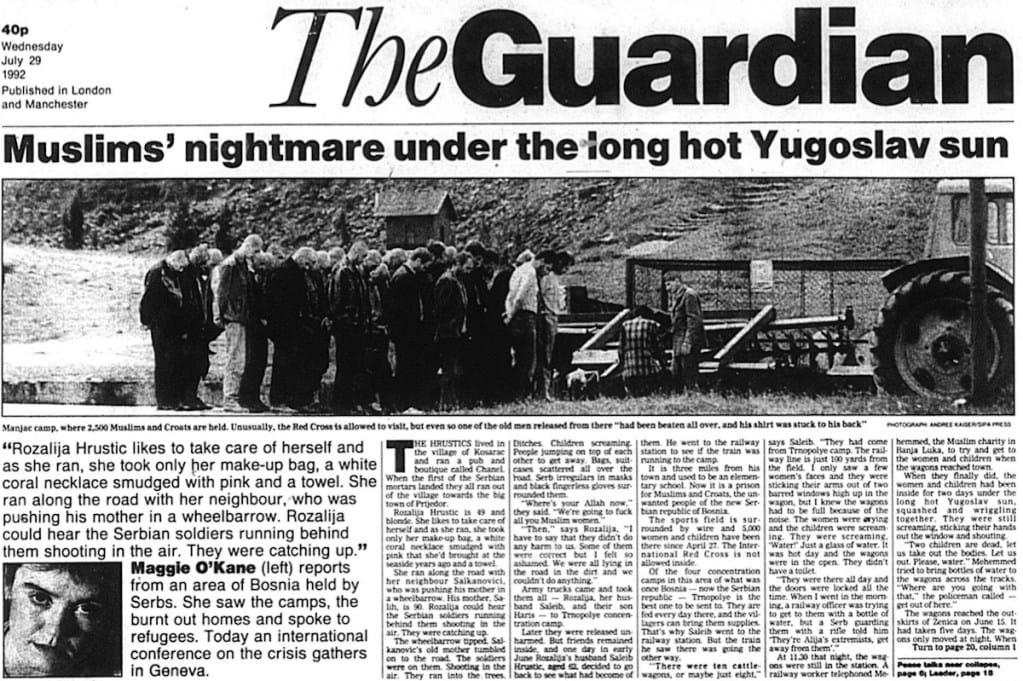

On 29 July, the Guardian ran a front-page story by correspondent Maggie O’Kane, who reported eyewitness and second-hand testimony about the camps from the regional capital of Banja Luka, and identified two additional sites at Trnopolje [Turn-OP-ol-yay] and Omarska which she too described as concentration camps. “We have cleaned Foča and Višegrad of Muslims,” a Serbian commander told her, “and now we will clean Gorazde.”

As it happened, Radovan Karadžić was in London that day to discuss a doomed EC-sponsored peace initiative. During an interview with Channel 4’s diplomatic correspondent Nik Gowing, Karadžić was presented with O’Kane’s dispatch and asked to respond. He protested that all reports of ethnic cleansing were false, and that civilians were being treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. “I invite,” he continued with something approaching insouciance, “any foreign correspondent to come to the Serbian part of Bosnia-Herzegovina and point out what city or town they would like to search for a concentration camp that is for civilians.”

Sue Inglish, the Foreign Editor of Channel 4 News, immediately telephoned Karadžić’s press officer and informed him she would have a team in Belgrade the following day. She then called Moscow correspondent Ian Williams to tell him he was going to the Balkans. Since joining Channel 4’s news team in 1989, Williams had reported on arms supplies to Iraq and the first Gulf War before relocating to the Soviet Union to cover the turmoil in its southern republics as the USSR unraveled. Inglish informed him he was to meet his field producer Andy Braddel, his cameraman-editor, and his sound recordist in Budapest, Hungary, the following day. From there, the four of them would take the night train to Belgrade and make immediate contact with Karadžić’s representatives.

At ITN, Foreign Planning Editor Vicky Knighton decided to send Penny Marshall on behalf of ITV (Channel 3), along with a cameraman and sound recordist. Like Williams, Marshall was an experienced foreign-affairs reporter who had spent years covering Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. If she turned up a story in Bosnia, a producer and an editor would be sent out to help prepare the report for broadcast. Since ITN produced news content for both Channel 4 and Channel 3, the two teams would work collaboratively and pool their footage. At the Guardian, meanwhile, Maggie O’Kane passed the Yugoslavia portfolio to her colleague Ed Vulliamy, who joined the ITN trip.

On 1 August, Ian Williams and his team rendezvoused with Penny Marshall’s crew and Vulliamy in Belgrade. Marshall and Williams had been faxed copies of the Gutman and O’Kane articles, along with a list of alleged concentration camps sites obtained from the Bosnian Muslim authorities. They showed that list to Karadžić’s people and identified the camps they wished to visit. They then set about conducting interviews with local NGO representatives and visiting some of the nearest sites. They found nothing untoward at an army barracks in Belgrade and a refugee centre in Loznica.

The following morning, Newsday ran another dispatch by Roy Gutman, in which the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Zagreb speculated that Omarska was a “death camp.”3 The Serbs, however, were stonewalling. Ian Williams telephoned Sue Inglish in London to report that, Karadžić’s offer notwithstanding, Serbian officials were profoundly unenthused by the prospect of British journalists inspecting the Bosnian sites. Inglish said she would telephone Karadžić’s press officer, and at 5am the next morning, the reporters were flown by helicopter to Pale in Serb-controlled Bosnia to meet Radovan Karadžić himself.

When he arrived, Karadžić was evasive. The trip the journalists wanted to make, he announced gloomily, would be extremely dangerous. Handing them a site list of his own, he recommended a trip to Sarajevo, where they could report on Serbs being mistreated in Muslim-run camps instead. Unimpressed, the reporters pointed out that they couldn’t vindicate Serb denials unless they were permitted to inspect the Prijedor sites mentioned in O’Kane’s and Gutman’s reports. They were by now particularly anxious to visit Omarska. And if he didn’t grant them the unrestricted access he had publicly pledged, people would naturally conclude that the Serbs had something to hide. Did they? Karadžić acquiesced. Very well, he told them, they would go to Omarska, and they would be free to look at whatever they wished there. “You have my word,” he said.

On 5 August, the two ITN teams and Vulliamy were taken to Prijedor town, the regional hub from which the camps were administered. As they drove from Banja Luka where they had spent the previous night, they passed the shattered remains of Kozarac. Before it was razed by Serbian artillery and arson, the town was home to 26,000 Muslims—now it was a blasted husk. Upon arrival in Prijedor, the reporters were shepherded into a murky smoke-filled room inside a municipal building, where members of the local Crisis Staff responsible for managing the camps delivered a lecture about the Serbs’ history of persecution, and then announced that it would not be possible to go to Omarska after all. A fraught back-and-forth ensued, until finally the journalists were told to stand outside while phone calls were made.

While they waited, the reporters approached a queue of Muslim women and girls huddled outside the police station under armed guard. Their men, they whispered, had all been arrested and taken to Omarska, to Trnopolje, and to Keraterm. At length, the reporters were informed that an armed convoy had been arranged and would set off that same afternoon. They would be the first journalists to set foot inside the Omarska and Trnopolje camps.

II. “Raw-boned and Lantern-jawed”

Omarska was a mining complex used by the Serbian authorities during the war to hold Bosnian Muslims and Croats captured or expelled during the ethnic cleansing of Prijedor. In his August 2nd Newsday dispatch, Gutman had reported that Prijedor’s entire political and cultural elite were interned there, and that international human rights agencies suspected “systematic slaughter” was occurring “on a huge scale.” But at the time the ITN convoy rolled up at its heavily guarded perimeter, neither the ICRC nor the United Nations had been permitted to confirm these reports, or to affirm the Serbs’ description of the facility as a mere transit centre.

Upon entering the camp, the reporters recorded internees being drilled in groups of thirty across a yard from a large hangar and into a canteen. There, skeletal men sat hunched in silence over meagre servings of thin soup and stale bread. “I do not want to tell any lies, but I cannot tell the truth,” one of them told Marshall when she asked him about the conditions there. The men were allowed less than five minutes to collect their food and eat their only meal of the day before another thirty arrived to replace them. “The internees are horribly thin, raw-boned,” Vulliamy reported in the Guardian the next day. “Some are almost cadaverous, with skin like parchment folded around their arms [and] their faces are lantern-jawed.” Although the men they were permitted to see were badly malnourished, he was careful to note that “none of the 80 inmates we saw showed signs of violence or beating.”

At a briefing given by the Prijedor Chief of Police’s translator-cum-spokeswoman, Nada Balaban, the reporters were told that Omarksa was a processing hub and “investigation centre,” where detainees were categorised according to their status as fighters or civilians, and then sent on to the relevant camp for trial or deportation out of Serb-controlled areas of Bosnia. The reporters told Balaban they wanted to see the internees’ living quarters. Absolutely not, came the reply. “We’ve only seen the canteen,” Williams protested. “Why are you not fulfilling Dr. Karadžić’s promise to us?” “He promised us something else,” Balaban shrugged. And, with that, they were sent back to their buses.

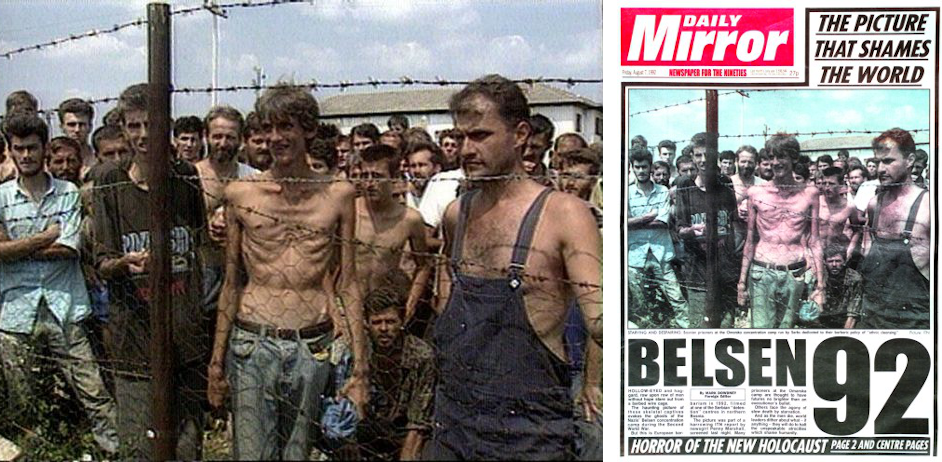

When the convoy pulled up outside Trnopolje, the reporters were greeted by the sight of hundreds of men fenced into a repurposed primary school, milling about aimlessly in the 90-degree heat. Marshall, Williams, and Vulliamy approached different parts of a barbed wire fence, behind which the men were gathered, and began conducting interviews. Marshall struck up conversation with a gaunt young Muslim named Fikret Alić across the wire. Stripped to the waist, Alić’s body was so wasted by starvation that his ribs jutted over his sunken stomach. “It is a prison camp,” Vulliamy reported Alić as saying, “but not a PoW camp. We are not fighters. They came to our village, Kozarac. I was near my house [when] they put us on the buses and brought us to Keraterm for a while, and then here.” The reporters heard stories of hundreds of prisoners being murdered in Keraterm and Omarska.

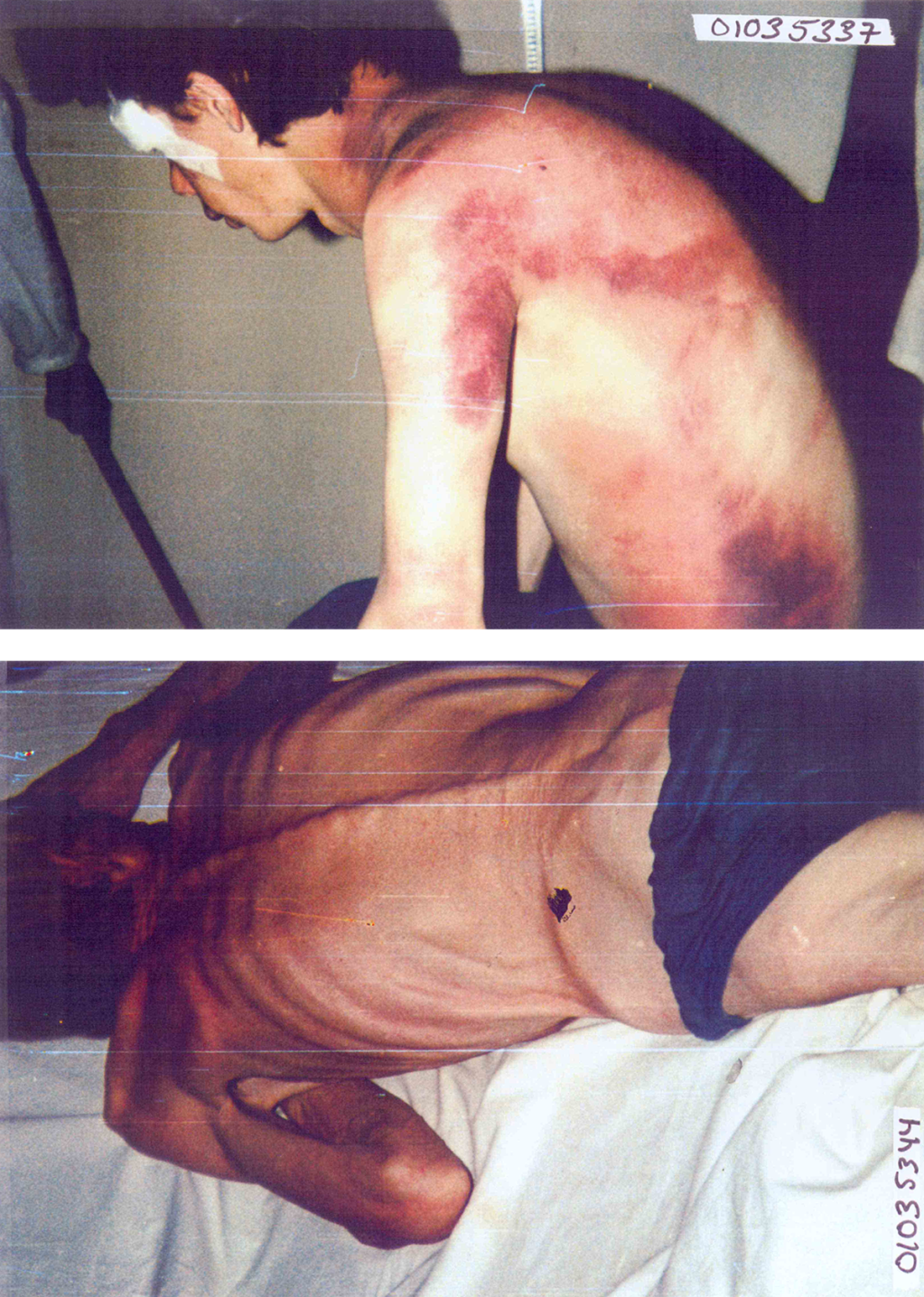

At the camp’s makeshift medical centre, Marshall interviewed a Bosnian Muslim doctor named Idriz Merdžanić who nodded when asked if he had to treat beaten prisoners. When Marshall’s Serbian minder left the room, Merdžanić passed the reporter a small camera containing a roll of undeveloped film that he had kept hidden in the clinic’s toilet cistern. Marshall concealed it beneath her flak jacket. The photographs it held—of broken and emaciated bodies brought to Merdžanić for treatment—would appear in both Williams’s and Marshall’s reports.

As the two ITN crews and Vulliamy drove back to Belgrade that evening, they discussed what they had seen. Omarska was the more concerning of the two sites, they agreed, if only because access to most of it had been forbidden. What had the Serbs violated Karadžić’s public promise to conceal? But the reporters also agreed they did not have enough information to definitively describe either facility as a “concentration camp,” given the term’s inflammatory historical connotations. When they reached Belgrade that night, Marshall and Williams called London to report their findings. It was agreed that the reporters would travel to Budapest to edit their reports the following morning, and then send them back to London by satellite link for transmission the same evening.

The reports by Ian Williams (above) and Penny Marshall4 broadcast on August 6th, 1992, and Ed Vulliamy’s Guardian article the following morning, caused a sensation. ITN and Vulliamy had not described Omarska and Trnopolje as concentration camps, but that didn’t detain the tabloid press. The wretched figure of Fikret Alić at Trnopolje’s barbed wire fence had appeared in both Marshall’s and Williams’s reports, and it immediately became an iconic image of the Bosnian war. The Daily Mirror and the Daily Star both splashed with Alić’s picture over the headline “Belsen 1992.”

Readers and viewers recoiled, and Western diplomats and leaders issued stern statements of concern. But there was scant appetite for military intervention—it would be another three years before decisive NATO operations against Serbian positions began. On the ground, the ICRC were finally admitted to some of the Prijedor camps and began registering detainees. Omarska was closed before the end of August. At Trnopolje, the fencing came down within days, and prisoners were permitted greater freedom of movement. In November, that camp was also shut down.

But if the prisoners’ circumstances appeared to be improving, those appearances were deceptive. As the world would later learn, internees were simply shipped to other camps or murdered. On 21 August, a Serbian convoy collected over 200 prisoners from Trnopolje, including the camp’s sick and wounded, and informed them they were to be released as part of a prisoner exchange. Instead, they were driven to the Korićani Cliffs on Mount Vlašić, where Serb soldiers ordered them to disembark, lined them up on their knees, and shot them. The violence in the Balkans would continue to escalate unchecked, reaching a crescendo of insanity during eleven days of genocidal slaughter at Srebrenica in July 1995. Three weeks of NATO military operations eventually began on 30 August after the Serbs shelled a marketplace in Sarajevo, killing 43 people and injuring 75 more. The Dayton Peace Accords, which partitioned Bosnia and finally brought the war to an end, were signed on 14 December.

The British journalists’ 1992 visit was an important development in the way that the war was understood in the West, but it was one among many. In the subsequent months and years, Serb atrocities would be independently reported by numerous other journalists, NGOs, and diplomats. And in 1993, as the war raged, the UN established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague to investigate and try crimes against humanity and war crimes committed by all sides during the Balkan wars.

The following year, the tribunal’s prosecutors approached ITN and requested copies of the raw unedited footage (known as “rushes”) that its journalists had shot in Omarska and Trnopolje on 5 August 1992. As a rule, news organisations are wary of cooperating with law enforcement and criminal justice authorities, lest they become a target of those seeking to discredit a prosecution. Nevertheless, under the highly unusual circumstances, ITN cooperated. This decision was the first in a chain of events that would entangle the news organisation and its two reporters in an ugly public scandal three years later. They would first learn of it when an obscure radical magazine issued a press release announcing an exclusive exposé.

III. The Riddle of the Wire

Thomas Deichmann first met Mick Hume at the end of the 1980s, around the time Deichmann was completing his civil engineering studies and Hume had just become founding editor of the Revolutionary Communist Party’s monthly magazine, Living Marxism. Deichmann was in London visiting a friend, who introduced him to Hume and other members of the Living Marxism/RCP circle at a summer conference they were holding. The two men remained in touch, and after Deichmann founded the independent German language publication Novo in 1992, their magazines would print translations of one another’s articles every now and then.

A product of the usual declension of far-Left feuds and faction fights, the Revolutionary Communist Party was an eccentric political sect established in 1977 after its members were ejected from the Revolutionary Communist Group. The RCP’s theorist-in-chief was Frank Füredi, a professor of sociology at the University of Kent, and under his unorthodox guidance, the party began to defend positions that sounded—perversely, for a Marxist organisation—libertarian. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the RCP repositioned itself as a defender of Enlightenment values. Free speech and progress, Living Marxism informed its readers, would now be the order of the day.

But these people were by no means liberals. Living Marxism may have been launched by Mick Hume in 1988 as a forum for the discussion of the party’s ideas, but it was generally a lot less clear what the magazine stood for than what it stood against. Hume and his writers hated—inter alia—environmentalism, animal rights activists, the “nanny state,” gun control, censorship, and media panics. And almost everything they printed was marinated in a thoroughgoing detestation of the middle-class liberal metropolitan elite and its cherished values. By the same contrarian token, if something appalled the loathsome chattering classes, it would usually be energetically defended in Living Marxism.

From time to time, valuable points would emerge—the magazine could be, by turns, thought-provoking, maddening, inane, obnoxious, refreshingly iconoclastic, and profoundly tiresome, occasionally all within the space of a single article. But none of this had anything much to do with socialism. As former RCP member Don Milligan would later reflect:

Young RCP comrades, contacts and full members, were by and large simply not socialists. It took an unconscionable length of time for this to dawn on me, and to recognise fully that the party leaders, Frank Füredi, Michael Fitzpatrick, and Mick Hume, were not socialists either. They were, of course, Leninists of the purist kind, virulently hostile to the rest of the labour and socialist movement, and committed absolutely to a life without illusions and sentiment.

This allergy to sentiment was most evident in Living Marxism’s fanatical anti-imperialism—a Cold War doctrine that required absolutist opposition to the projection of Western power, and that held Western moralising about democracy and human rights in contempt. Hume was a particularly vehement opponent of what became known as the “journalism of attachment”—an idea proposed by the BBC war reporter Martin Bell, following his experience reporting from Sarajevo. What Bell was advocating, journalist John Lloyd later wrote, was “an engaged journalism, which bears witness to horrors and deliberately stirs the consciences of the mass audience and of public men and women who have the power and command the resources to put a stop to them.”

To Hume the anti-sentimentalist and anti-interventionist, this thinking was anathema, and he inveighed against it repeatedly in the pages of Living Marxism. In 1997, he published a 28-page pamphlet on the subject entitled Whose War Is It Anyway?, in which he derided Bell’s notion as vainglorious, manipulative, sentimental, and dangerous. “The Journalism of Attachment,” Hume wrote, “is ultimately a moral crusade for Western governments, through the United Nations and NATO, to take forceful action against those accused of genocide and war crimes by intervening around the world.”5

Still, it is easier to oppose intervention intended to halt atrocities, if doubt can be cast on whether atrocities are being committed at all. Even the most pitiless anti-imperialist will be tempted every now and again to argue that things really aren’t as bad as all that—they will accuse the media of bias, they will quarrel with stories of massacres and attack the credibility of those who tell them, they will contest the numbers of dead and displaced, and they will furiously denounce Western double-standards and moral hypocrisy.

The same temptation that led Noam Chomsky to deny the Cambodian genocide, led Living Marxism to propagandise for a particularly vicious Serbian nationalism, despite Hume’s insistence that his magazine had no ideological stake in the conflict. Hume claimed that Living Marxism’s positions were the product of dispassionate analysis, not moralistic emotion, and yet his magazine’s articles about Bosnia seethed with righteous indignation. As the bloodletting in the Balkans intensified and Western opposition to Serbia grew, Hume and Deichmann both began publishing articles about anti-Serb bias in the media, accusing Western journalists of warmongering, fearmongering, and even anti-Serb racism.

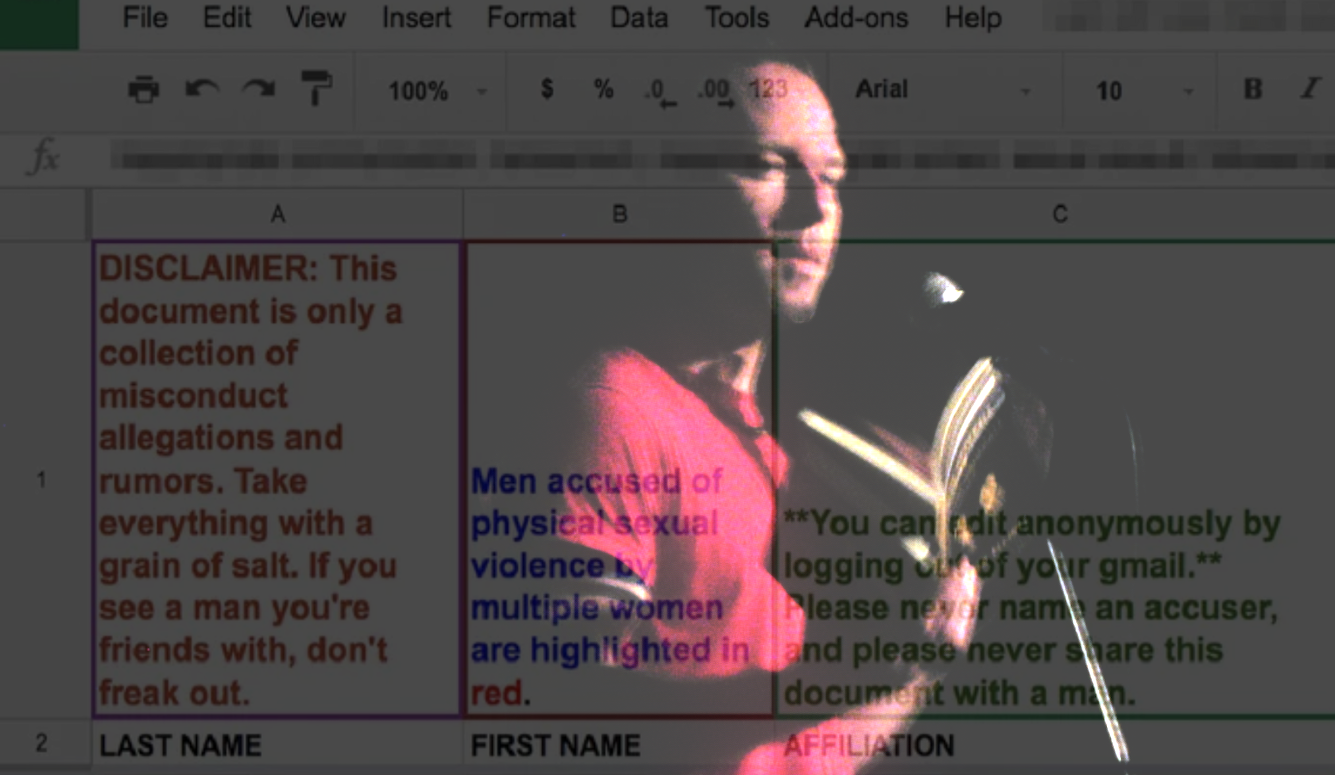

Deichmann’s interest in this topic did not pass unnoticed in Europe. When the war ended, he was contacted by a Dutch lawyer named Mischa Wladimiroff, who was then representing a former Serbian politician and paramilitary fighter named Duško Tadić at The Hague. Tadić had been charged with committing a litany of war crimes in the Prijedor region, including at the Trnopolje, Omarska, and Keraterm camps. Wladimiroff hoped to show that much of the testimony against his client had been gleaned from Western media coverage not personal experience, and so he asked Deichmann to prepare an analysis for the defence of German reporting on the case.

While Deichmann was working on his report in The Hague, Wladimiroff mentioned that he had spoken to a former guard at the Trnopolje camp about the barbed wire fence in ITN’s famous pictures of Fikret Alić. The fence, the guard had explained, predated the war and had encircled a barn adjacent to the camp, not the camp itself. The ITN journalists, he surmised, must have filmed Alić from inside this compound. Wladimiroff passed Deichmann a stack of videotapes he had obtained from the ICTY prosecutors and invited him to take them away for examination. Among these tapes were the unedited ITN rushes shot by the two teams on 5 August 1992.

It was Deichmann’s wife who would identify an incongruous detail in the Trnopolje footage. If the barbed wire had been intended to imprison Alić and the other men in the camp, she asked, then why was it fixed to the inside of the poles? When a fence turns 90 degrees, it will usually wrap around the outside of the corner-post, so that the tension pulls the wire into the post and not out of it. The barbed wire in the ITN footage was on Fikret Alić’s side of the pole—ergo, the fence must have been encircling the journalists.

Deichmann decided he had stumbled onto something important. On 9 November 1996, before he left The Hague to return to Frankfurt, Deichmann recorded an interview with Wladimiroff about the fence. Then he telephoned Mick Hume in London and explained what he had discovered. Would Living Marxism be interested in running a story about British media malfeasance during the Bosnian war? Hume was most certainly interested. Deichmann said he would be flying to Trnopolje to conduct further research, and promised to keep Hume informed. He arrived on 4 December and spent three days taking photographs and conducting interviews aided by a translator. When he returned to Germany, he wrote up a draft for publication in Novo and emailed a translation to Hume.

Hume was thrilled. By late 1996—seven years after the fall of the Berlin Wall—the Revolutionary Communist Party was finally being dissolved by its leadership, and its members were reorganising. In the new year, publication of Living Marxism would shift to InformInc, a new company created by former RCP members Claire Fox and Helene Guldberg. And in February, the now-defunct Party’s magazine would be rebranded and relaunched as LM. Hume decided that Thomas Deichmann’s exposé would be the cover story of LM’s inaugural issue.

In a short accompanying editorial entitled “First Casualty?,” Hume took the opportunity to revisit his vendetta against Martin Bell and the journalism of attachment. “When truth is deemed to be in the eye of the beholder,” Hume wrote, “the line between reportage and propaganda can get stretched thinner than a string of barbed wire. If every picture tells a story, then it is surely part of a war reporter’s job to ensure that story is true.” He then added, somewhat confusingly: “Here at LM we see nothing wrong with taking sides. We tend to be something of a partisan publication ourselves. Taking sides, however, cannot be an excuse for taking liberties with the facts.”6

The finalised copy was sent to be printed on 15 January 1997, and Hume instructed his press officer Jan Macvarish to draft a press release announcing Deichmann’s sensational scoop. On 23 January, the day the boxed copies of the magazine returned from the printers, Hume issued the press release to a wire service for immediate distribution. And then he waited.

IV. Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be

Deichmann’s claim that a barbed wire fence had not encircled Trnopolje was the most carefully evidenced in his article. It was also the only claim that would survive the libel trial three years later. That he would turn out to be correct on this narrow point is part of what has allowed confusion to be created about how much of his essay was vindicated in court. But the arrangement of the fencing at a Serbian prison camp five years previously was not, by itself, much of an exclusive. As the title of his essay indicated, the fence was the incriminating clue to a more sinister story of media mendacity and public credulity—like a matchbook carelessly discarded at a crime scene, the significance of which only the amateur sleuth understands.

What made Deichmann’s story sensational was his allegation that the ITN reporters had deliberately misrepresented the fence in order to misrepresent Trnopolje itself. The consequences of that deception, he reminded readers, had been grave—the image of Alić had produced an inflammation of hysterical warmongering among media and political elites, which had led in turn to the demonisation of Serbs and (eventually) Western military intervention. The architects of this hoax had succeeded in fooling everyone until Deichmann began poring over ITN’s raw footage at The Hague. But now he had uncovered the secret the ITN reporters had attempted to conceal.

So, why had the ITN reporters lied? And about what, exactly? The ITN trip to Bosnia, Deichmann claimed, was the result of media hysteria about human rights abuses. Inflamed by Roy Gutman’s and Maggie O’Kane’s lurid dispatches (which, Deichmann took care to mention, “drew heavily on hearsay and unconfirmed claims”), Western editors were now demanding more stories of Muslim suffering and Serbian cruelty. And so, Ian Williams, Penny Marshall, and Ed Vulliamy had all been packed off to the Balkans “under intense pressure,” with orders not to return until they had found evidence of Serbian concentration camps. “As the end of their trip approached, however, the British news team had been unable to find the camps story they were after,” Deichmann revealed. “Their final stop was to be the refugee camp at Trnopolje, next to the village of Kozarac which had been overrun by Bosnian Serb units a few months earlier in May 1992. This was to be their last chance to get the story which their editors wanted.”7

Having watched the unscreened camera footage that ITN’s teams never imagined anyone would see, Deichmann announced that he had made some startling discoveries. Not only was the barbed wire unrepresentative of the fencing at Trnopolje, but Fikret Alić was unrepresentative of the condition of the camp’s general population. The reporters, presumably fearful of returning to London empty-handed, had contrived to combine these two elements (using “camera angles and editing”) into an image guaranteed to evoke memories of Hitlerian death camps, even though they knew that Trnopolje was nothing of the kind. “It was not a prison,” Deichmann insisted bluntly, “and certainly not a ‘concentration camp,’ but a collection centre for refugees, many of whom went there seeking safety and could leave again when they wished.”8

And Trnopolje was really not such a bad place to be under the circumstances. “We protected Muslims,” a former camp guard told Deichmann, “from Serbian extremists who wanted to take revenge.” “We wanted to help the Western journalists at the time,” complained the wife of another. “We had no idea how the Western newspapers work.” He interviewed a member of the Serbian Red Cross who “stressed that this was no internment or prisoner camp; it was a collecting camp for exiled Muslims. Everybody I spoke to confirmed that the refugees could leave the camp area at almost any time.” They had come to Trnopolje, he said, “of their own free will for protection.”9 Even the leader of the British Liberal Democrat Party at the time, Paddy Ashdown, had visited the camp a few weeks after the ITN reports, and described it as a refugee camp to which Bosnian Muslims fled voluntarily. And Ashdown, Deichmann pointed out, “is no ally of the Bosnian Serbs.”

The first mention of abuse came 29 paragraphs into Deichmann’s article, and consisted of these two short sentences: “Without doubt most of the refugees in Trnopolje were undernourished. Civilians were harassed in the camp, and there were reports of some rapes and murders.” Deichmann’s use of the passive voice carefully obscured the question of responsibility. His mention of “reports of” rapes and murders made such claims sound doubtful, and the qualifier “some” made them sound rare. “Yet the irony,” he immediately added, “is that if this collection centre for refugees had not existed under the supervision of Bosnian Serb soldiers, a far greater number of Muslim civilians might have lost their lives.”10

Deichmann even claimed that the outcry provoked by the broadcasts had foreclosed the possibility of Muslims being permitted to remain in Prijedor, thereby implicating ITN and its reporters in the ethnic cleansing of the region. “In a sense,” he wrote, “the exile of thousands of Muslims from their home in Bosnia-Herzegovina was thus inadvertently facilitated by the international reaction to the ITN reports from Trnopolje.”11 The message was neither subtle nor hard to understand: unethical Western journalists had abused the trust of the locals and deceitfully misrepresented Trnopolje as some kind of earthbound hell, when in fact it was a refuge for which the Bosnian Muslims ought to have been grateful. This was the anti-Serb calumny Deichmann’s article was written and published to expose.

The barbed wire fence was not only evidence of a deception, but the key to the other side of the looking glass, through which Deichmann invited his readers to make an inferential leap: if the fence was not what it appeared to be, then maybe nothing about the Bosnian war was what it appeared to be. This allowed him to unveil an alternate reality, hitherto concealed from the public, in which concentration camps were refugee collection centres, the Serbs were victims not victimisers, careful reporting was propaganda (and vice versa), and Western governments were thirsting for military conflict instead of cravenly appeasing Serbian aggression to avoid it.

In retrospect, it is astonishing that Deichmann’s article was taken seriously at all, so wildly were his claims at variance with what had long been established. By the time it was published in February 1997, the purpose of Trnopolje and the other Serb-run camps was no longer the mystery it had been in August 1992. Copious reporting and first-hand testimony had uncovered the horrifying conditions at these facilities, their functional importance in the Serbs’ genocidal campaign to ethnically cleanse northern Bosnia, and the pitiless cruelty with which the detainees were treated by their captors. Deichmann ignored all that. He even ignored the photographic evidence of beatings and torture passed to Penny Marshall by Trnopolje’s doctor, Idriz Merdžanić, and he barely mentioned Omarska at all, to which the first half of both Penny Marshall’s and Ian Williams’s reports had been devoted.

A number of reporters familiar with the facts of the war, including Ed Vulliamy, vehemently disputed his revisionist portrayal of Trnopolje. The false claims Deichmann had made about Penny Marshall’s and Ian Williams’s reporting were harder to disprove five years after the fact, because copies of the broadcasts were not readily accessible, and most people’s recollection of them was poor. These would be picked over in court. But, in the meantime, discussion of Deichmann’s elisions, distortions, and mistakes would soon be drowned out by a furious row about whether or not LM had a right to print them at all. And, for the next three years, the contested truth about Trnopolje got lost in the din.

V. “A Wicked Lie”

On the morning of 24 January 1997, ITN’s Editor-in-Chief Richard Tait got a call from his press office alerting him to a story the Press Association was running about ITN. It included this quote attributed to someone named Thomas Deichmann, who was described as “an expert witness to the UN War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague”:

“I am shocked that over the past four and a half years, none of the journalists involved has told the full story about that barbed wire fence which made such an impact on world opinion. The photograph has been taken as proof that Trnopolje was a Nazi-style concentration camp, but the journalists knew that it was no such thing.”

Tait was stunned. This was the first he was hearing of these claims. Had no-one at LM approached ITN for comment? “The PA is the standard press agency for all newspapers, radio stations, and television companies,” Tait would later testify. “So, my first thought was that, while I was reading it, virtually everybody else in British journalism could be reading it as well.”12 Calls were already arriving from news organisations asking for comment, and from ITN’s clients and partners seeking reassurance that ITN’s Bosnian reporting—which many of them had broadcast—had been on the level.

Tait called ITN’s chief executive, Stewart Purvis. In 1992, Purvis had been Editor-in-Chief at ITN, and had supervised the broadcast of the Marshall and Williams reports from Bosnia, so he was already familiar with the material. Appraised of the contents of the press release, he instructed ITN’s lawyers to fax LM a letter informing them that “these defamatory allegations are wholly false.” The letter further demanded an apology and an undertaking not to repeat the allegations, the pulping of the February issue of LM, damages, and legal costs. If these demands were not met, libel proceedings would begin forthwith.13

But instead of intimidating LM and its supporters, the libel threat galvanised them. Neither Mick Hume nor the magazine’s publishers could afford to pay damages and costs, so they had already passed the point of no return. Even if they had been in a position to meet ITN’s demands, it is safe to say Hume would have refused to do so. Having spent his adult life jabbing at the establishment, he wasn’t about to prostrate himself before his antagonist now that he had its attention. Besides which, he was certain he was right. So LM responded with a second press release the same day, in which Hume was quoted as saying:

“[ITN’s] gagging order is a scandalous attempt to scare us off and stifle public discussion of these important issues. Neither ITN nor their lawyers has yet said a word about the substance of our story, which exposes the way that those famous pictures were taken.

We stand 100 percent behind Thomas Deichmann’s article. There is one simple way to resolve this issue. ITN should show the full, unedited footage which its team filmed at Trnopolje on the 5 August 1992. Then everybody will know the truth.”

ITN were not about to do that. So, instead, Tait obtained an advance copy of LM’s February issue from Nick Higham at the BBC, who, Tait was alarmed to discover, seemed to be taking a sympathetic interest in LM’s point of view. Having read Deichmann’s article and Hume’s accompanying editorial, Tait re-watched Ian Williams’s and Penny Marshall’s reports and the surviving rushes. He then interviewed the reporters who had travelled to Bosnia in the Summer of 1992. And he pored over back issues of Living Marxism in an attempt to figure out who on earth he was dealing with. When he had finished, he reported his conclusions to Stewart Purvis.

Deichmann’s article, Tait told Purvis, was “a wicked lie from a weird fringe organisation with a track record of supporting the Bosnian Serbs and of vilifying the previous reporting of the camps by Roy Gutman.”14 ITN should make good on its threat to sue, Tait advised, in defence of its reputation and the reputations of its journalists. On 25 January, LM issued yet another press release demanding that the British Academy of Film and Television Arts and the Royal Television Society rescind the awards they had given to the ITN teams for their Bosnia reporting. “The revelations published in LM magazine,” the press release declared, “highlight important issues concerning journalistic standards and the responsibilities of war reporters.” On 31 January, as LM’s February issue began appearing on the shelves of British newsagents, ITN filed a writ for libel.

The row consumed ten pages of LM’s March 1997 issue, most of which were filled by Hume himself, either under his own name or under the alias “Eddie Veale.” In a two-page editorial, Hume defended Deichmann’s article and redoubled his attack on ITN, lecturing its journalists on the merits of objectivity and deriding the journalism of attachment he accused them of practicing. Hume would return to this theme repeatedly during the weeks, months, and years after Deichmann’s article was published.

Hume and Deichmann called a press conference at Cyberia, a London internet café established by a former RCP colleague, at which Deichmann played his tapes, repeated all the allegations in his article, and again called for ITN’s awards to be returned and for the ITN rushes to be made public. LM supporters and former RCP members picketed ITN’s offices and distributed copies of the magazine’s press releases to passers-by. A supporter of the magazine began harassing Penny Marshall on her home telephone number. Another invaded the 1997 RTS Awards dinner to present Stewart Purvis with a “Golden Gag” trophy at his table in front of Marshall and her husband. (At trial, Hume would deny any involvement in, or foreknowledge of, stunts like these.)

The controversy produced a flurry of bad-tempered exchanges in the op-ed and letters pages of the British press. LM and its supporters were now attacking ITN on two fronts. Not only were its reporters corrupted by bias, but the organisation was trying to strong-arm its detractors. “Th[is] magazine now faces a long and very costly legal battle to establish our freedom to publish the truth,” Hume wrote in the March issue. “Britain’s libel laws are a censorship charter which the rich can hire to silence their critics. Those who believe in the freedom of the press must surely oppose this attempt by a multi-million pound corporation to buy immunity from criticism through the courts.”15 The BBC’s World Affairs Editor John Simpson was minded to agree. On 14 September 1997, he wrote a review of Hume’s pamphlet Whose War Is It Anyway? for the Sunday Telegraph, in which he warmly recommended Hume’s thoughts on the journalism of attachment, and wondered “whether a powerful organisation [like ITN] should really try to pursue a small, intelligent magazine such as LM through the courts.”

To ITN’s gathering dismay, Hume’s attempt to reposition himself as a martyr to free expression began to attract the attention and support of the kind of media professionals and cultural elites LM ordinarily despised. At one time or another, authors Fay Weldon, Doris Lessing, Margaret Drabble, JG Ballard, journalists Michael Gove, Roy Greenslade and Auberon Waugh, former Conservative MP George Walden, and (naturally) Noam Chomsky all wrote columns or signed letters or made statements in support of the embattled magazine. Hume would later boast that 150 public figures had offered LM their solidarity. By the time the case came to trial, its fundraising appeal (which they christened “Off the Fence”) had raked in an impressive £70,000. “The battle,” Hume defiantly announced in March 1997, “has only just begun.”16

Hume seemed to be enjoying himself. For all his furious complaints about the grotesque injustice visited on his magazine, Hume’s writing from that time reads like the bugle call of a happy warrior. At fundraisers and in the pages of LM, he inspired his supporters with paeans to press freedom, and denounced the moral turpitude of his enemies. He spurned an offer from ITN in September 1997 to forego damages and settle for a retraction and apology, and said he’d see them in court. “If a cave-in is what ITN expects,” he had already declared, “we advise them not to hold their breath. LM stands by Thomas Deichmann’s story, and is prepared to fight all the libel orders they can throw at us.”17

On the eve of the trial three years later, Hume was sounding less sure. “I am confident about our case,” he wrote (in what would be the magazine’s penultimate issue), “less so about the justice of Britain’s notorious libel laws.” And then he led his troops over the precipice.

The concluding part of this essay can be read here:

References:

1 Herman, Edward. (2006). “The Approved Narrative of the Srebrenica Massacre,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. 19. 409-434. 10.1007/s11196-006-9031-z.

2 Witness to Genocide by Roy Gutman (Prentice Hall & IBD, 1993) p 29.

3 Ibid. pp 44–49.

4 Penny Marshall’s News at Ten report can be seen on Getty’s website in two parts, absent the section featuring Idriz Merdžanić’s photographs.

5 Whose War Is It Anyway? by Mick Hume (InformInc, 1997) p 15

6 Editorial “First Casualty?” by Mick Hume, LM, February 1997, p 5

7 “The Picture that Fooled the World” by Thomas Deichmann, LM, February 1997, p 27

8 Ibid. p 24

9 Ibid. p 29

10 Ibid. p 30

11 Ibid. p 31

12 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 6

13 Trial transcript, Day 1, pp 18–19

14 When Reporters Cross the Line by Jeff Hulbert and Stewart Purvis (Biteback, 2013) p 23

15 “The Mag ITN Wants to Gag,” by Mick Hume, LM March 1997, pp 16–17

16 Ibid. p 16

17 Ibid. p 17