History

Denial and Defamation—The ITN-LM Libel Trial Revisited, Part II: The Trial

The more someone invests in a lie, the more painful it becomes to renounce.

VI. The Standards of Western Journalism

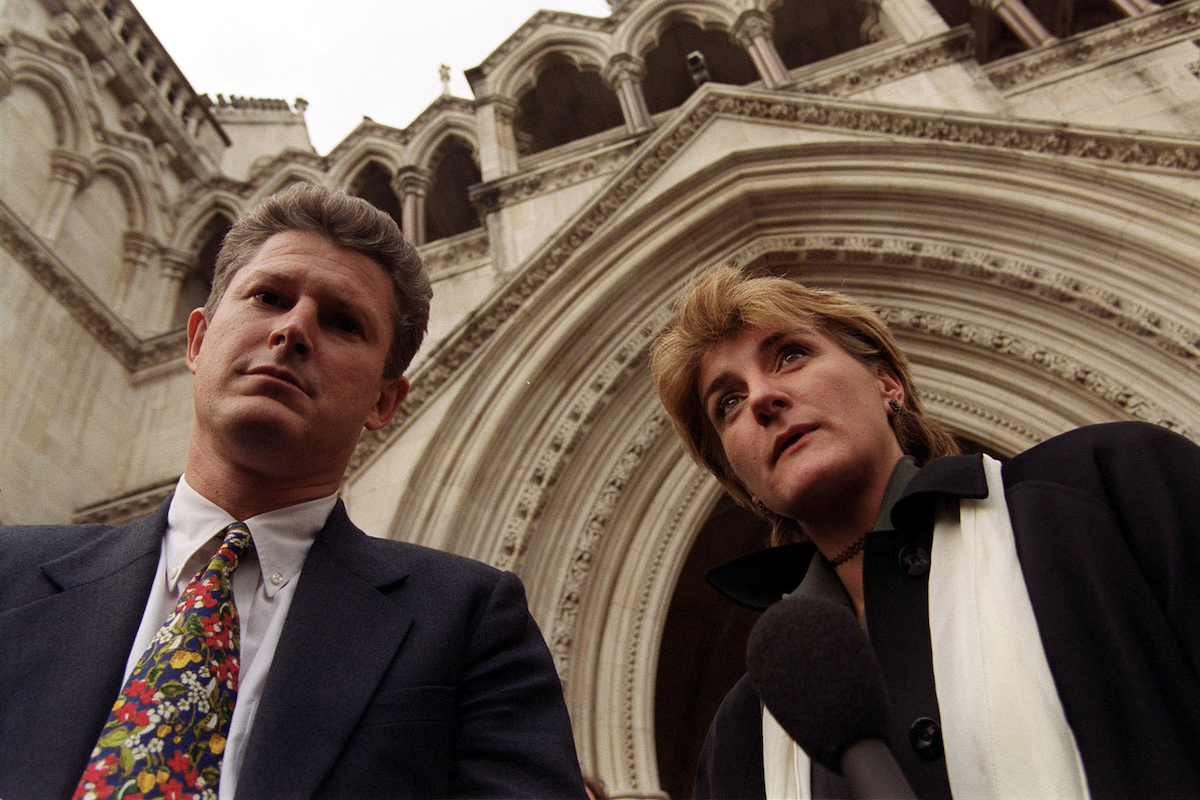

The trial eventually began at the High Courts of Justice in London on 28 February 2000. The defendants—recorded as Michael Hume, InformInc (LM) Ltd., and Helene Guldberg—arrived at court on the heels of a disappointing pre-trial hearing. The presiding judge, Mr. Justice Morland, had ruled the testimony of a number of key defence witnesses, including the BBC’s John Simpson, inadmissible. He was not interested in rehearsing the debates about the journalism of attachment or press freedom that had convulsed the chatterati for three years. The claimants—recorded as Independent Television News Ltd., Penny Marshall, and Ian Williams—held that Deichmann’s article, Hume’s accompanying editorial, and the first LM press release were all false and defamatory. Under Britain’s controversial libel law, the defendants were required to show that their contested claims about ITN’s reporting were true. Morland simply wanted to establish if that was the case.

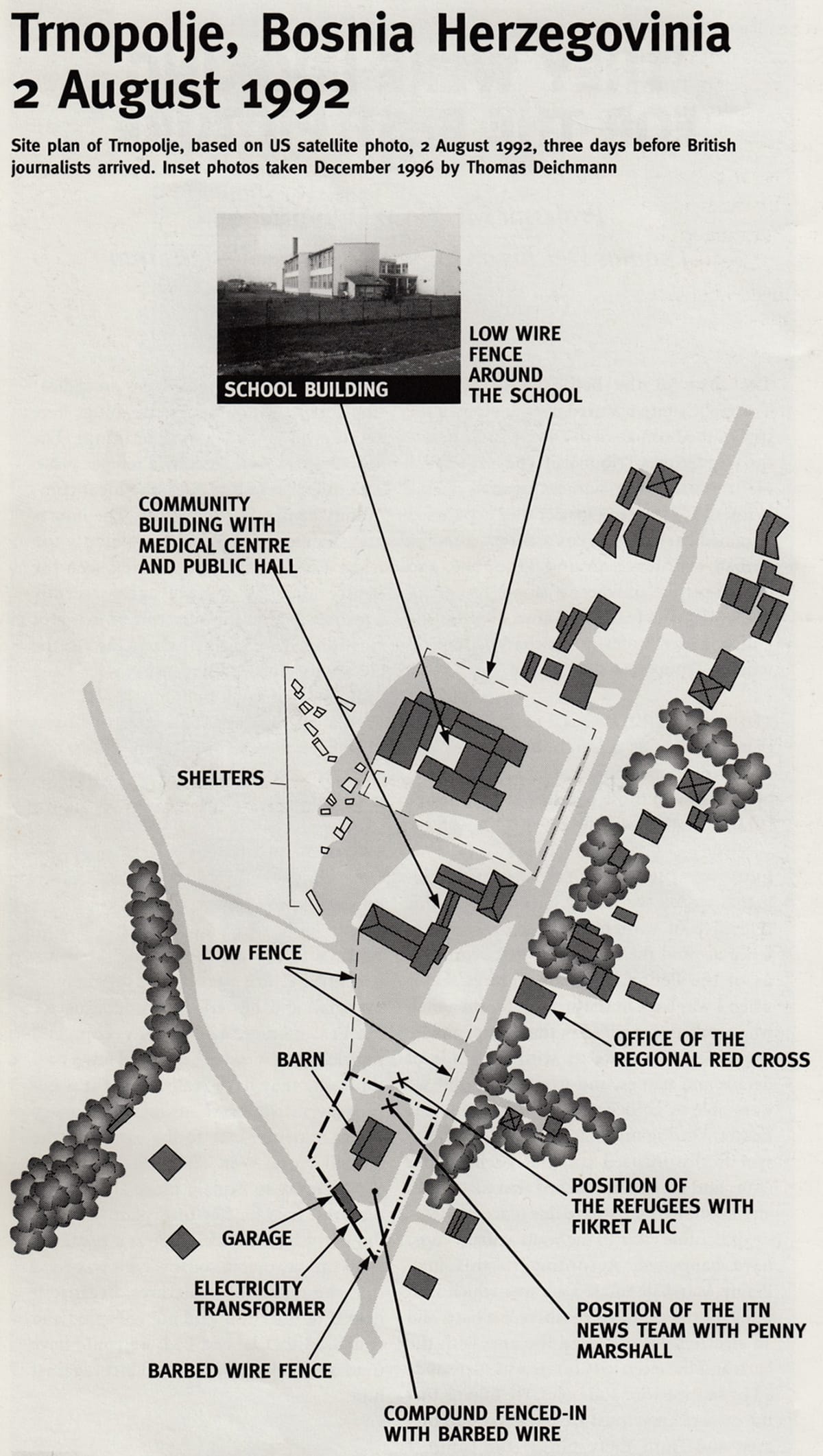

The defence’s priority was to establish the location of the barbed wire fence at Trnopolje. This their lawyer Gavin Millar successfully accomplished by leading the claimants’ first witness, Ian Williams, through a glacial examination of the ITN rushes during cross-examination. The court then waited for evidence of a conspiracy at ITN to suppress this information. But instead, when Millar rose to cross-examine Andy Braddel, Ian Williams’s field producer for Channel 4, he simply repeated the tortuous process from scratch. Having dismissed the jury at the end of another long morning on the fourth day of the trial, Justice Morland was moved to ask if this was really necessary: “We seem to be spending a very large amount of time on stuff which seems to be obvious to me, but it may not be obvious to the jury and I may have got it wrong.”18 The claimants’ lawyer Tom Shields readily agreed. It was not the position of the fence, he pointed out, that the claimants disputed, but LM’s allegation of journalistic duplicity.

Needless to say, the picture of ITN’s journalism offered by its reporters and management in court bore scant resemblance to Deichmann’s. Contrary to his claim that the British media were hungry for stories of atrocities in the Summer of 1992, the earliest reports by Maggie O’Kane and Roy Gutman were met with widespread scepticism. Until Williams, Marshall, and Vulliamy filed their dispatches from northern Bosnia, there was a general reluctance to believe that ethnic cleansing and death camps could possibly be a feature of modern Europe. Channel 4’s Foreign Editor Sue Inglish testified that she was mindful of the fact that all sides in the conflict used propaganda to manipulate foreign journalists,19 and ITN’s Foreign Planning Editor Vicky Knighton admitted she had been doubtful the reporters would find camps like those Gutman and O’Kane had described.20

Nor had any pressure been brought to bear on the reporters to return with one finding or another. All testified that they were given an open-ended brief: confirm or disconfirm the reports of concentration camps in northern Bosnia—there would be an important story either way. The seven ITN witnesses who had been to the Balkans on 5 August 1992 all testified that they assumed the barbed wire was part of the Trnopolje camp’s fencing and had been unaware of standing in any kind of compound. As Andy Braddel pointed out, they had been told that Trnopolje was not a purpose-built facility, so they had no reason to expect uniformity in the fencing, which was unsurprisingly makeshift and haphazard.21

The ITN rushes lent some support to this account. The section of barbed wire abutting the camp was sagging in places but more or less intact, and appeared to have been reinforced with new fencing. But the rest of what had once been a compound was in a state of considerable disrepair. What remained of the fencing was distressed, torn, and missing entirely in places and the area was clearly capacious enough to avoid the sensation of being penned in. The reporters were shadowed by Serbian guards and anticipated that they might be ejected without notice, as they had just been ejected from Omarska. So, in the limited time available, they devoted their attention to the shocking condition of the people behind the wire, and not the wire itself.

“During my entire stay at this camp,” Ian Williams testified, “my focus was on the people imprisoned in the compound. Part of the wire imprisoning them was barbed wire. Frankly, I was concentrating on those people, not on the different make-up of the wire surrounding them.”22 Penny Marshall and all the other members of the two ITN teams who followed Williams onto the stand said the same. It was the most obvious and parsimonious explanation for their misapprehension, but it was one Deichmann and Hume didn’t appear to have considered. Despite his best efforts, Millar was never able to elicit an admission to the contrary from anyone he cross-examined.

In the absence of a confession, Millar then wasted a good deal of time trying to get the ITN reporters to admit that one of them had viewed the Trnopolje footage before they reached the editing suite in Budapest. I’m still not certain why this question merited such dogged pursuit, but it yielded nothing and was referenced only briefly in Millar’s closing argument. He also interrogated some of the ITN witnesses about a “dope sheet” (a document logging and describing the shots in a sequence) that LM had decided was suspicious, but this avenue of inquiry proved so unrewarding that Millar didn’t refer to it in his closing remarks at all.

Under the stress-test of cross-examination, ITN’s reporting held up well. The reports reminded the jury that Penny Marshall had interviewed a sympathetic young Serbian guard name Igor, and both management and reporters testified that the language used in the report was given careful consideration. And Channel 4 did something that LM did not—they approached the subject of their story and invited a response to their reporting, which Radovan Karadžić duly provided immediately after the broadcast. (Vulliamy’s Guardian article had also closed by reporting the Serbs’ response.)

LM’s journalism held up less well. By the time he began his opening speech for the defence on the eighth day of the trial, Millar was ready to argue that most of ITN’s complaints were caused by a misunderstanding. LM, he claimed, had never meant to imply that ITN had pressured its reporters to produce a sensationalist anti-Serb story. In fact, there was nothing defamatory about ITN in the article, its accompanying editorial, or press release at all. Nor did LM believe there had been a conspiracy at ITN. “Where is this said?” Millar asked the jury rhetorically. “The word ‘conspiracy’ does not appear anywhere in the article.”23 There were two problems with this strategy. First, the jury had the original article in front of them, so they did not have to take Millar’s summary on trust. Second, by disowning so much of what Deichmann had written and clearly intended to convey, the defence were tacitly admitting that his article had gone too far.

It is, of course, true that the word “conspiracy” had not appeared in Deichmann’s article. But it is also obvious that a conspiracy was its intended suggestion. If, as his essay implied, the deception was accomplished by selective editing, then that implicated two field producers, two editors, as well as Marshall and Williams in a conspiracy of at least six people. And this assumed that the rest of the crews and all of ITN’s editorial staff were kept in the dark. Asked under cross-examination how many of the ITN journalists who travelled to Trnopolje that day had participated in the plot to fool the world, Hume was understandably reluctant to be drawn. He would only identify Marshall and Williams (who were, after all, already suing him).24

The defence had by now disavowed Deichmann’s theory that these two reporters had misrepresented Trnopolje to satisfy an editorial appetite for concentration camp stories. So, instead, they were forced to rely on Hume’s accusation that Williams and Marshall had become emotionally attached to the cause of the Bosnian Muslims, who they perceived to be noble victims. “Once journalists see fit to appoint themselves as the judge of who is ‘good’ and who is ‘evil’ in a conflict such as Bosnia,” Hume had instructed in his editorial, “you know you are in trouble. The role of objective reporter of fact sits uneasily with that of moral crusader.”25 On the stand, Hume took the opportunity to restate these objections with such passion and stridency that Morland interjected, “You are beginning to make a speech.”26 But Hume even retreated from this argument when he was cross-examined by the claimants’ lawyer that same afternoon:

Shields: Is it part of your case that [Marshall and Williams] were not objective when they set out to Belgrade and then on to north Bosnia?

Hume: No that is no part.

Shields: It is not part of your case that they were wedded to the cause of Bosnian Muslims?

Hume: Absolutely not. I never suggested anything of the sort. I have no idea of the political views of either of those journalists.

Shields: Are you suggesting that they have lied to this court when they said that they would file the report, whatever they found?

Hume: Well, I have no idea whether they have told lies to this court.27

By this stage, Hume didn’t seem to know what his case was. When Shields beseeched him to explain it, Hume answered with uncharacteristic uncertainty: “Well, the case, as I understand it, Mr. Shields—and my legal knowledge is limited—the case is as pleaded, which I think my counsel outlined this morning.” Shields had to ask Hume to explain his case another four times before he finally answered, “It is my case that they were inside a barbed wire surrounded enclosure.”28

Thomas Deichmann had a scarcely more comfortable time when he finally took the stand. Under cross-examination, he acknowledged that one of the former guards he had interviewed had not been at the camp when the ITN reporters visited, and so was unable to speak to conditions there at that time given that they rapidly improved immediately after the reporters left. This also applied to the comparatively benign description of Trnopolje provided by the British Liberal Democratic Party leader Paddy Ashdown, which Deichmann had quoted in his article and which Hume referenced repeatedly at trial. And Deichmann admitted that a Serbian Red Cross worker’s claim that “no fence had been erected” at the camp was “completely untrue” but that he had reported it without caveat anyway.29

In a sign that things were going badly for the defence, the jury passed a number of questions to the judge while Hume and Deichmann were testifying asking the defence to clarify points of argument or fact. They had asked Hume twice why he had failed to approach ITN or its reporters for comment before deciding to publish. Now that Deichmann was on the stand, they cast a sceptical eye over a map he had produced to accompany his LM article.

Deichmann had misleadingly depicted the tattered remains of the barbed wire fence as an unbroken enclosure, and the fence surrounding the camp as incomplete. Why, the jury asked, did the fence on the east side of the camp suddenly discontinue leaving what appeared to be a large gap through which people could freely walk in and out? Deichmann replied that his representations of the fencing had been gleaned from the ITN rushes. When he was preparing the map, he didn’t have the tape covering that part of the camp, so he just left the fence out.30 But, the jury persisted in a second note, “Did you consciously show the area on your map where Ian Williams and Penny Marshall were as complete and the area where the prisoners were with spaces in the fencing to strengthen your claim that Mr. Williams and Miss Marshall were enclosed and the prisoners had freedom of movement?”31 Deichmann shrugged that he had simply depicted the barbed wire fence in accordance with the conventions he learned as a civil engineer.

In court, and during the immediate outcry that followed publication of Deichmann’s article, Hume was keen to emphasise how fastidious he and his writer had been. “Thomas Deichmann’s LM article,” Hume wrote in the March 1997 issue of LM, “was based on the careful study of hours of unedited (and largely unbroadcast) videotape shot by the ITN team during their visit to Bosnian Serb-run camps.”32 It was this unseen footage that had allowed Deichmann to conclude that ITN’s edited report had distorted the true nature of Trnopolje:

[A]n important element of that ‘key image’ [of Fikret Alić] had been produced by camera angles and editing. The other pictures, which were not broadcast, show clearly that the large area on which the refugees were standing was not fenced-in with barbed wire. You can see that the people are free to move on the road and on the open area, and have already erected a few protective tents. Within the compound next door that is surrounded with barbed wire, you can see about 15 people, including women and children, sitting under the shade of a tree. Penny Marshall’s team were able to walk in and out of this compound to get their film, and the refugees could do the same as they searched for some shelter from the August sun.33

But most of the footage mentioned in this oddly bucolic passage had been included in ITN’s reports. Penny Marshall is shown entering what remained of the barbed wire compound through a gap in the fencing upon her arrival at Trnopolje, passing the people on the grass. A shot of the makeshift tents was also included, and both Marshall’s and Williams’s reports had featured abundant footage from the east and west sides of the camp that clearly show the low chain-link fence, the existence of which they were supposed to have concealed. In fact, the footage shot at the barbed wire accounted for only a small fraction of both reports, and it had appeared in the middle of the report, and not at the front where it would have been placed if the intention had been to sensationalise it. Had Deichmann and Hume not realised any of this?

Late in the trial, Deichmann made a startling admission that raised the possibility they had not. Although he had carefully studied the ITN rushes, Deichmann revealed that he hadn’t had access to the edited reports, and hadn’t watched them since they were first broadcast in 1992.34 If he was relying on a five-year-old memory of two six-minute news reports he’d watched once, then it’s not surprising he had got so much wrong. This would also explain why his article had made no mention of the photographs of abuse passed to Penny Marshall by Idriz Merdžanić, since they hadn’t been among the video rushes he’d acquired from Waldimiroff at The Hague.

But Hume had (implausibly) testified that he’d somehow managed to obtain copies of both reports from “a student supporter from one of the many media studies departments that are proliferating around the country, that kind of collect news coverage.” And he had watched those tapes, he said, “very, very carefully.”35 Deichmann, meanwhile, said that he had worked from “very, very detailed” transcripts of the reports that he had obtained from ITN.36 If Hume had indeed eyeballed the reports prior to publication, and if Deichmann’s transcript was (as he seemed to imply) sufficiently detailed that it served as an adequate substitute for the reports themselves, then Deichmann’s claims about what Marshall and Williams had excluded during the edit were deliberate misrepresentations and Hume knew it.

For all his lamentations about the journalism of attachment, Hume was a political pamphleteer, to whom the whole idea of dispassionate commentary was foreign. And like all political pamphleteers, he was self-certain, self-righteous, dogmatic, and furious. When he launched Living Marxism in 1988, Hume had described his target audience as “young, angry, thinking people,” and boasted that, “I think of myself as a communist who writes propaganda, rather than as a journalist who happens to be left-wing.” In January 2007, when he handed over the editorship of Spiked-Online to his deputy, Brendan O’Neill, he reflected on “twenty years as the editor of publications that, I am happy to say, have published great propaganda—in the proper sense of the word, propagating ideas.” In 1997, those ideas included the notion that Western journalists venturing into war zones to report on humanitarian outrages were conspiring to mislead the public.

Hume was good at what he did. An intoxicating cocktail of theory, rhetoric, and bombast had served him well before the trial as he drummed up support and sympathy for his magazine. But propaganda is designed to inflame passions, not withstand careful examination. It’s one thing to feed a likeminded readership innuendo and conjecture about media corruption, and quite another to defend it in a court of law. He told the jury that he resolved not to approach ITN for comment because, although he was certain Deichmann’s claims were ironclad, he feared ITN would seek an injunction to suppress LM’s story—a fear retrospectively vindicated by the organisation’s recourse to libel. It is more likely that he knew his allegations were evidentially weak, but was convinced of the truth of them regardless. And that being the case, he had no option but to publish and, if necessary, be damned.

Hume firmly denied that he was motivated by a grudge against Western journalists in general, or ITN’s journalists in particular. “What I am concerned about,” he announced in court, “is the standards of Western journalism.” On this count, he was altogether more bothered by the mote in ITN’s eye than the beam in his own. In a defiant article for the Times following the verdict, Hume would complain that, “We could not win because the law demanded that we prove the unprovable—what was going on in the ITN journalists’ minds eight years ago.”37

But that was Hume’s own fault. He and Deichmann had ascribed motives to journalists for which they had no evidence. Had they not relied on mind-reading in support of their allegations, they would not have found themselves asked to defend mind-reading in court.

VII. A Product of Serbian Extremism

As the trial progressed, a striking difference emerged in the way the two sides spoke about the Trnopolje camp. Penny Marshall and Ian Williams and the other ITN witnesses testified to the human hardship and cruelty they found there. But during endless hours spent shuttling backwards and forwards through harrowing video footage of emaciated prisoners, Gavin Millar barely mentioned the internees at all. Instead, he would direct his witness’s attention to the fence-posts, to the sagging barbed-wire, to the low mesh fencing, to the community centre in the background, to the foliage, and to Deichmann’s map.

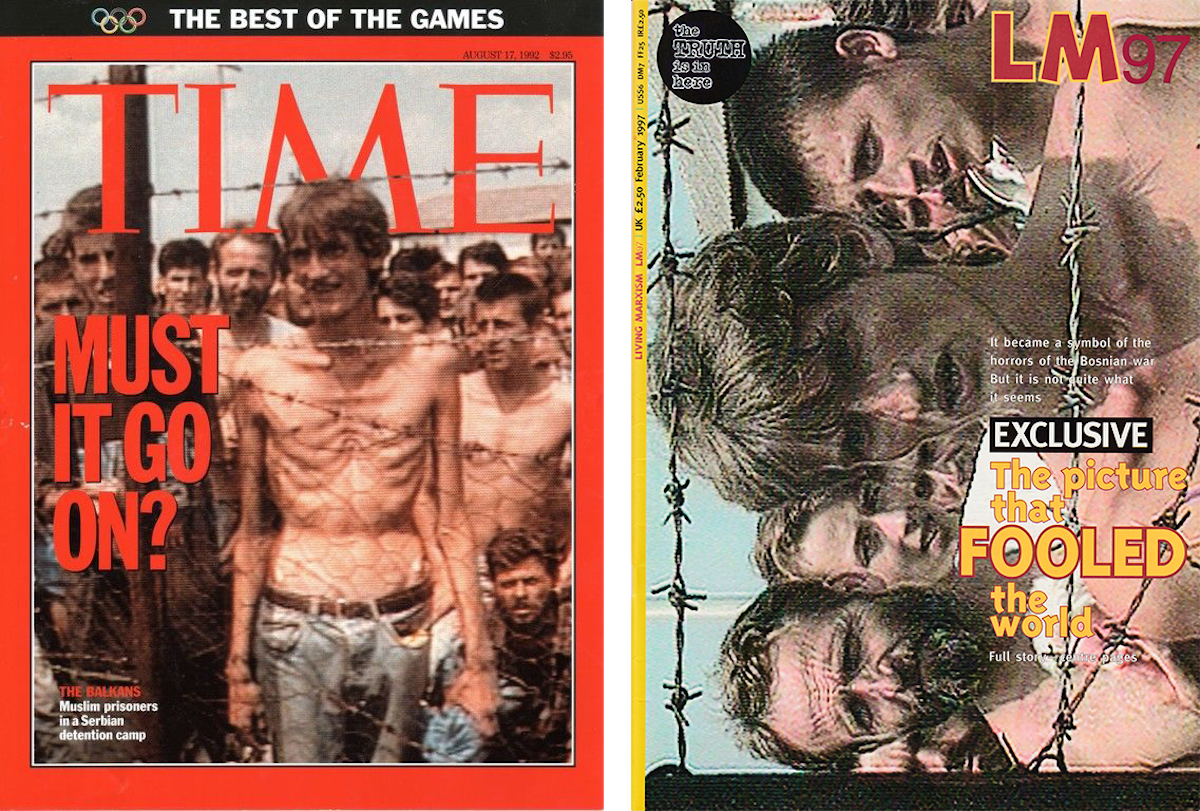

Penny Marshall had watched the cross-examination of her colleagues from the court, and when she was called to testify, she made a perceptive observation. Pressed under cross-examination to acknowledge that the image of Fikret Alić and—particularly—the barbed wire “had assumed some significance as far as other media commentators and newspapers were concerned,” Marshall replied, “Well, I understood that the image of Alić had become important because people were appalled by his condition, yes. But you look at the picture and see barbed wire; I look at the picture and see Fikret. That is the difference between us.”38

By the time Deichmann visited Trnopolje in December 1996, the war was over and the camp itself had been closed for four years. The purpose of his visit was to not to establish whether or not human rights abuses were being committed but to investigate Mischa Wladimiroff’s suspicions about the fencing. That Wladimiroff should have prodded a young journalist in this direction is not so mysterious: his task at The Hague was to defend Duško Tadić, a Serb accused of committing atrocities in the Bosnian camps. So, he introduced Deichmann to the possibility that the Trnopolje camp was not what it seemed, and indicated that the key to unravelling this falsehood was hidden in the ITN footage. Already predisposed to defend the Serbs from a hostile Western press, Deichmann fastened on the anomaly of the fence to the exclusion of everything else. And, in his article, he encouraged his readers to do likewise.

This myopia suited Hume just fine. In his lengthy March 1997 editorial for LM defending Thomas Deichmann’s story, Hume rehearsed his weariness with those who, “in Bosnia and elsewhere, have pioneered a new ‘feminised’ school of war reporting, one which declares that it is less interested in politics and armies than in ‘people.’” This studied indifference to human wellbeing was even reflected in the cover art for the February issue. Rather than reproducing the still of Fikret Alić’s ravaged torso splashed across the world’s press in 1992, Hume and his designers used a cropped, medium close-up of Alić and set it at right angles to the text. This awkward arrangement emphasised the wire, of course, but it also gave a misleading impression of Alić’s overall condition by excluding the worst effects of his starvation from the frame. (Much smaller black and white images of Alić’s full torso could be found inside on the front pages of the tabloids Hume reproduced.)

Deichmann and Hume were excited by a story of Western media corruption and Serb villainization, to which the Bosnian Muslims were peripheral. So, for the most part, they just ignored them. Deichmann’s article included multiple interviews with Serb locals and former camp guards, and he dutifully recorded their complaints that Trnopolje had been misrepresented and misunderstood. But he published no interviews at all with Bosnian Muslim refugees, some 40,000 of whom lived in Germany after the war, and many of whom had passed through the Serbs’ camps after they were driven from their homes. More astonishing still, Deichmann had apparently made no effort to locate either Fikret Alić or Idriz Merdžanić, the Trnopolje camp doctor who had passed Penny Marshall his camera.

Merdžanić was the only witness called for the claimants who did not work for ITN, and he took the stand on the morning of the seventh day of the trial. Testifying through an interpreter, Merdžanić told the court that he had been working as a general practitioner in a small village practice in Prijedor when war broke out in 1992. On May 26th, he had been arrested by the Serb army and interned in Trnopolje. Two other doctors had been brought to the camp from Kozarac. The Serbian guards, some of whom had been his patients, recognised him, and so he was taken to the camp’s clinic and ordered to treat the sick and wounded. He had no medicine, no electricity, and no water, and he was made to sleep on the floor of the filthy surgery.

Down a short hall was a room called “The Lab,” where, Merdžanić said, prisoners would be brought to be beaten. The three doctors would listen to the sounds of violence and suffering until the stricken victim was carried in by his tormentors to be revived. Male prisoners were assaulted with wooden chair legs. Women were raped by the Serbian soldiers at night. The other two doctors were transferred to Omarska, where one of them was murdered. Merdžanić testified that changes were made to the camp immediately before the reporters arrived in anticipation of their visit and that there were further rapid improvements after their reports were broadcast. And he spoke of how he had watched 240 men and boys board the convoy out of Trnopolje on August 21st, 1992, that would take them to their deaths at the Korićani Cliffs.39

And to all this—amazingly—the defence had nothing to say. Gavin Millar indicated that he would forego cross-examination and Idriz Merdžanić was excused, his testimony unchallenged.40 The court would hear from another 11 witnesses, but the trial was effectively over. In his article, Deichmann had left his readers with the unmistakeable impression that Trnopolje provided Bosnian Muslims with a refuge from Serbian extremism. In court, Ian Williams had called the camp “a product of Serbian extremism.”41 The defence had just tacitly acknowledged that Williams was correct. Trnopolje was worse than Williams and Marshall had felt able to report on the available evidence, and as bad as they had feared.

In court, Hume and Deichmann were now at pains to emphasise that Trnopolje had indeed been a heinous place and Hume took particular umbrage at the suggestion “that somehow this article describes this hell-hole of a place as a holiday camp. I have made it absolutely certain that that is not the case.”42 “Is it your case,” Shields asked Hume, “that Mr. Fikret Alić and the other inmates in the field were free to leave Trnopolje on 5 August 1992?” It was not, Hume replied. “[Alić] is in a field surrounded on two sides by low wire fencing, outside of which there are armed guards, the north side of which abuts the community building and the south side of which abuts a barbed wire compound within which the ITN crews were filming and within which there are other armed guards.”43

The purpose of Deichmann’s article, Hume explained, was “not to enter a discussion about what this camp was, it was about what the camp was not—a Nazi-style concentration camp.”44 What most particularly bothered him about this conflation, he said, was “the misuse of the Holocaust in the discussions of the Yugoslav civil war and other conflicts around the world.”45 This “new kind of obsession with the Holocaust,” he declared, distorted the present by flattening the complexities of the war into a monochromatic morality play, and it distorted the past by robbing the Holocaust’s “unique horror” of its exceptionalism.46

This peculiar argument had made no appearance in Deichmann’s article, Hume’s editorial, or the LM press release that the court had been asked to examine. It was, however, a longstanding talking point that allowed the magazine to use ostensible respect for the Holocaust’s memory to shield the Serbs from accusations of genocide. In a lengthy and thoughtful two–part analysis of the trial for the Journal of Human Rights in 2002, the Australian political scientist David Campbell argued that this enabled “the potential link between Bosnia and the Holocaust to be cut, the meaning of the Bosnian war to be diminished, and the responsibility of those who perpetrated the ethnic-cleansing campaigns to be denied.”47

Acknowledgement of Serbian criminality by LM was invariably qualified with the observations that “all sides” were guilty of atrocities, and that those atrocities, while regrettable, were nonetheless unremarkable in the context of modern warfare. They therefore provided no justification for special condemnation, much less Western military intervention. Campbell speculated that if Hume was drawing on the thinking of American historian Peter Novick, then he had ignored an important caveat. In The Holocaust and Collective Memory, Campbell noted, Novick had written that “a moment’s reflection makes clear that the notion of uniqueness is quite vacuous. Every historical event, including the Holocaust, in some ways resembles events to which it might be compared and differs from them in some ways. These resemblances and differences are a perfectly proper subject for discussion.”48

LM’s censorious efforts to invalidate that discussion, Campbell argued, precluded its writers or readers from engaging in a sophisticated understanding of the Bosnian camps, which, like the Nazi camps before them, were part of a system established to serve a “larger political and military strategy”:

As the indictments for genocide issued against the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadžić, Momčilo Krajišnik, and Ratko Mladić by the ICTY prosecutors make clear, the operation of “camps and detention facilities,” in which “tens of thousands” of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats were held, was integral to the strategy of creating “impossible conditions of life, involving persecution and terror tactics, that would have the effect of encouraging non-Serbs to leave . . . the deportation of those who were reluctant to leave; and the liquidation of others.”49

It is important to bear in mind that by the time LM published Deichmann’s article in February 1997, none of this was controversial. On October 6th, 1992, UN Security Council Resolution 780 had authorised a Commission of Experts to collect evidence on human rights violations in the Balkans. They reported their findings to the UNSC President on May 24th, 1994, which included twelve annexes, one of which—Annex V: The Prijedor Report—looked at the Omarska, Trnopolje, and Keraterm camps in detail.

As the ITN reporters and Ed Vulliamy had correctly intuited, Omarska was by far the more lethal of the two facilities. Around 700 Bosnian Muslims perished there during the three months the camp was operational. In a small building called the White House, prisoners were taken for beatings and torture. The Red House was where prisoners were taken for summary execution. “For the latter reason,” the authors note, “all reports about this building are from prisoners who have not been inside it themselves. There are limited numbers of survivors of the White House.” The prisoners were starved but would sometimes forego rations to avoid being beaten on their way to the canteen. By night, the guards would get drunk and build a bonfire and “allegedly organized sheer orgies in brute force and destruction. Some prisoners were victimized next to or in the bonfire, others in the White House, and some were walked towards the Red House. Some experienced two of these options.”

The bodies of those murdered would be displayed for the remaining prisoners to see the following morning. There were 37 women at Omarska who worked in the canteen, all of whom experienced brutal interrogation, many of whom were raped, and some of whom were murdered. Men were also sexually assaulted and humiliated. “Prisoners were, inter alia, forced to have homosexual intercourse with one another, close relatives—like fathers and sons—among them. Worst of all were numbers of reported castrations carried out by a variety of primitive means.” In conclusion:

All information available about Logor Omarska seems to indicate that it was more than anything else a death camp. The detainees were not there to work or serve a specific purpose. There is no information to sustain a claim that the detainees were in transit to somewhere else. As far as the prisoners were concerned, the interrogations led nowhere out of the camp, and the camp conditions were such that very few, if any, prisoners would have survived long-term detention.

Keraterm was similar to Omarska but smaller. Trnopolje was better than both, but still a godforsaken place to be. “The detainees in Trnopolje were more or less systematically deprived of their valuables and frequently also of their identification papers and other documents on hand.” Killings, beatings, and torture were “not rare.” Mass executions were carried out on at least four occasions. “The people killed in the camp were usually removed soon after by some camp inmates who were ordered by the Serbs to take them away and bury them.”

Is it possible that Thomas Deichmann simply didn’t know any of this? It is not. In his LM article, he had quoted the Report’s misapprehension that barbed wire had surrounded Trnoplje in an effort to discredit it. Nevertheless, he had confidently informed his readers that Trnopolje was a “collection centre for refugees” not a prison (a claim repeated in LM’s press release); that the detainees could come and go as they pleased; that the armed guards stationed around the camp were employed for their safety and protection; and that the camp had been “spontaneously created by refugees when the civil war escalated in the Prijedor region.” None of this was true. Even his repeated references to the internees as “refugees” was misleading, since it implied flight from fighting and background mayhem rather than a systematic campaign of Serbian expulsion and terror.

“If they are not very careful,” Hume had advised in his February 1997 editorial, “journalists who have some kind of emotional ‘attachment’ to one side can end up seeing what they want to see rather than what is really there.”50 And yet, it was Marshall’s and Williams’s reporting that more accurately reflected the reality of Trnopolje. It was LM, not the ITN reporters, who had allowed themselves to become pawns in a propaganda war, and who were “guilty,” as Hume put it in court, of taking sides in a foreign conflict. And they had done so for the very reason Hume held the journalism of attachment in such contempt—out of solidarity with those he and Deichmann considered the conflict’s true victims.

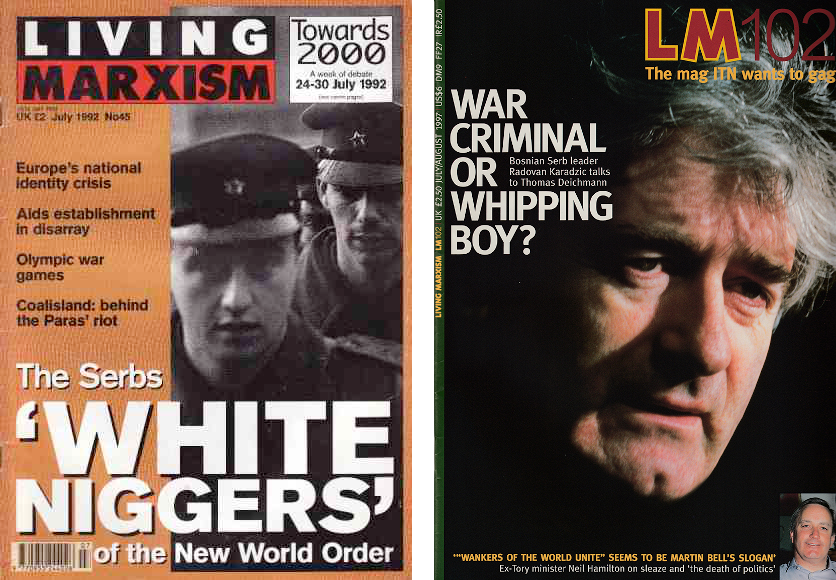

VIII. “White Niggers” of the New World Order

In the July 1992 issue of Living Marxism, published just as the Bosnian War was getting under way, Hume wrote a cover story under his alias “Eddie Veale” entitled, “‘White Niggers’ of the New World Order,” which promised to reveal “how and why America, Britain, and Germany have constructed the Serbian demon.” Asked by his lawyer to explain this article to the jury eight years later, Hume said this:

I wanted to very starkly—it is my headline—make the point that the Serbs, I felt, as the Bosnian war developed, were being talked about and illustrated and demonised in a way that was really a kind of new version of the old-fashioned politics of racial inferiority or being depicted as being sub-human. “Niggers” is a word that was historically used to degrade black people. I felt the Serbs were being given the same kind of treatment and that is why I called them the “White Niggers” of a new world order.51

Whenever LM was accused of pro-Serbian bias, Hume would reply that it was a complicated civil war, in which all sides were equally ghastly, and that the West should mind its own business. (He didn’t appear to realise that, in 1992, this was also the view of the US State Department.) LM was not pro-Serb, he’d protest, it was anti-anti-Serb. And in a narrow sense, that was true: Mick Hume was never a committed Serb nationalist, and his knowledge of the war in court proved to be cursory. The object of his antipathy was not the Bosnian Muslims, who barely seemed to enter his mind; it was the arrogant, sinful, hypocritical West. Inevitably, the distinction between pro-Serb and anti-anti-Serb began to erode until it disappeared altogether, and Living Marxism became, objectively, an appeaser of, and then a willing propagandist for, Serbian nationalism.

Evidence of pro-Serb bias within the pages of Living Marxism and LM is abundant, unambiguous, and damning. Some of this material was read out in court, and I don’t imagine it helped the magazine’s case much. Surprisingly, Thomas Deichmann’s interview with Radovan Karadžić in LM’s July/August 1997 double-issue was not mentioned during the trial. The cover of that edition was filled with a lugubrious portrait of the former Bosnian Serb leader, beneath the words, “WAR CRIMINAL OR WHIPPING BOY?” and the two pull-quotes selected to represent the interview inside read, “Nobody can count how many SERBS DIED because of these [ITN] pictures,” and “The Serb side HAS LOST AND SUFFERED most in this war.” [capitals in original]

At the time, Karadžić was a fugitive from international justice and in an unreflective mood. He pontificated about the persecution of the Serbs, shook his fist at the West, complained about the illegality and illegitimacy of the ICTY, accused ITN of taking advantage of his “naïve and trustful” nature, and suggested that Penny Marshall “should come out and tell the truth and clear her own conscience, and maybe apologise to the people.” To this, Deichmann offered very little resistance. “How do you feel,” he ventured, “when journalists compare you with German Nazis who were sentenced to death 50 years ago during the Nuremberg trials?” “Sometimes I laugh,” Karadžić replied, “sometimes I feel sorry for them…”

Radovan Karadžić was arrested in Belgrade on 21 July 2008, and I daresay hasn’t laughed much since. He was brought before the ICTY to answer charges of genocide, persecution, extermination, murder, ethnic cleansing, and various other violations of international law and crimes against humanity. On 24 March 2016, he was sentenced to forty years in prison, later increased to life on prosecutorial appeal. Not that this development will have embarrassed Mick Hume or his staff. Immediately following Deichmann’s congenial chat with Karadžić was a four-page essay by former RCP member Helen Searls entitled “Time to Put the War Crimes Tribunal in the Dock.” This one was discussed in court.

Duško Tadić was the Serbian militiaman whose defence Deichmann had assisted at The Hague in 1996. In his LM essay, Deichmann had been less than forthcoming about his role in the proceedings, introducing himself as “an expert witness to the War Crimes Tribunal” who had been “asked to present the tribunal with a report on German media coverage” of the Tadić trial.52 That made Deichmann sound like an expert on the Bosnian war (which he certainly was not) and implied that the ICTY had sought his media expertise, when in fact it had been solicited by Tadić’s defence counsel.

Deichmann had concluded his essay by noting with satisfaction that “by the end of October 1996, however, the accusations against Tadić had been dropped” after a prosecution witness was accused of perjury.53 Deichmann did not mention, however, that Tadić was still facing multiple additional counts of crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, and violations of the laws and customs of war. On 7 May 1997, three months after Deichmann’s story appeared, Tadić was found guilty on nine counts and partially guilty on a further two in the first judgement handed down by a tribunal of this kind since the Second World War. His crimes, the judgement declared, “consisted of killings, beatings, and forced transfers by Duško Tadić as principal or as an accessory, as well as his participation in the attack on the town of Kozarac in [the municipality of] Prijedor, in north-western Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

Searls took a dim view of all this, of course. She quarrelled with the legality of the Tribunal and the definition of “persecution,” and she objected to the absence of a jury and the admissibility of anonymous testimony. She particularly disliked the implication that Tadić was anything like Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, or Klaus Barbie. Compared to what the Nazis had done, she wrote, the crimes of which Tadić had been convicted “seem mundane and insignificant”—and certainly no worse than those committed by British and American troops in other theatres of conflict. The Tribunal may have deemed him a war criminal, but “in other eyes,” she advised, “Tadić might look like a fairly typical militiaman in the middle of any bloody civil war,” if perhaps a little “slap happy.”

Naturally, at trial, Hume defended Searls’s article but denied any sympathy for Tadić.54 He pointed out that he’d also published articles opposing the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and that “there are, so far as I know, no Serbs involved in the Rwandan conflict.”55 Nevertheless, Searls had presented Tadić as a victim of Western machinations, and made it perfectly clear that this was all very unfair. After all, “all of the more serious specific charges of gang rape, sexual mutilation, and murder were thrown out. In all he was found guilty of beating 14 Muslim men and of a ‘crime against humanity’ which is defined as ‘persecution.’”

Searls seemed to grant the ICTY the authority to acquit but not to convict. She was also less than candid about the available facts. Duško Tadić wasn’t merely “slap happy,” and Searls must have known this, because she indicated in her article that she had read the ICTY judgement. As ITN’s lawyer, Tom Shields, pointed out when these lines were discussed in court, Tadić was also found guilty of murdering two Bosnian policemen, and of aiding and abetting the sexual mutilation of Muslim men at Omarska.56 On June 18th, 1992, alone, Tadić participated in the beating, torture, and humiliation of six men in the hangar at Omarska. When one of them, Senad Muslimović, regained consciousness, Tadić threatened to slit his throat and then stabbed him twice in the shoulder. Muslimović was one of only two men to survive his ordeal that day. Enver Alić, Jasmin Hrnić, and Emir Karabašić were so badly mutilated that they didn’t leave the hangar alive. Tadić forced an unnamed prisoner to castrate Fikret Harambašić with his teeth, and Harambašić was then left to bleed out on the hangar floor.

Tadić participated in the cleansing of Jaskići in June 1992, before the village was razed, and he “played an active part in all phases of the attack on Kozarac.” It was there that he murdered two Muslim policemen who were being held under guard, by slitting their throats and then stabbing them both repeatedly. These two killings, the Tribunal found, “represent a major demonstration of a pattern of conduct consisting of extreme violence against non-Serbs and a flagrant disregard for human life and the suffering of others.”

On and on the judgement went, itemising Tadić’s sadism over forty pages. I detail some of his crimes here only to record the chasm between LM’s anodyne characterisation of Tadić and the depravity of his actual behaviour. Searls’s article followed the same pattern of Serbian exculpation and Western indictment as Deichmann’s. Both ostensibly took aim at targets outside the conflict (the ICTY and the British media, respectively), but betrayed their partisanship with a convergence of elisions and euphemisms designed to diminish, mitigate, or excuse Serbian culpability.

IX. To the Bitter End

All causes shall give way. I am in blood stepped in so far that should I wade no more, Returning were as tedious as go o’er.

~Macbeth

Mr. Justice Morland’s summing up on 14 March 2000, spelled doom for the defence. As he led the jury back over every claim and innuendo in Deichmann’s article, Hume’s editorial, and the first LM press release, the defamatory imputations and distortions the defence had done its best to deny and disavow were made newly apparent. Morland dismissed Deichmann’s and Hume’s testimonies in their entirety as irrelevant, since neither had been in Trnopolje on 5 August 1997, or Budapest the following day, and so neither were in a position to assess the motives of the reporters involved in the shoot or the edit. The only concession he made to the defence was this: “Clearly, Ian Williams and Penny Marshall and their TV teams were mistaken in thinking they were not enclosed by the old barbed wire fence, but does it matter?”57

Given the state of the fence, enclosed was an overstatement, but mistaken is the most important word in that sentence. In any event, the jury decided unanimously that it did not matter. ITN’s reporters had told the truth about Trnopolje, and they had been attacked by LM for having done so. The damages awarded by the jury were emphatic—£75,ooo to ITN, and “aggravated damages” (that is, libel aggravated by the subsequent conduct of the libeller) of £150,000 to Penny Marshall and Ian Williams each—the maximum Morland recommended in the event of a guilty verdict.

So unfavourable was the summing up to the defence that when Mick Hume encountered Morland shortly after the verdict, he remonstrated with the judge about it. “I always try to sum up straight down the middle,” came the reply, “but I find sometimes the middle is more to one side than the other.” His Lordship was gently trying to tell Hume that he’d had no case, but Hume wasn’t in a hurry to take this on board. “We are not going away,” he announced in a statement released after the verdict, “and we will not keep quiet about the concerns that led us to publish Thomas Deichmann’s article and, reluctantly, to fight this case: freedom of speech, journalistic standards, and the exploitation of the Holocaust.”

In the years after the trial, some of LM’s most high-profile defenders rethought their support for the magazine and apologised publicly. There are those who continue to object (as Geoffrey Wheatcroft did at the time) that British libel law is not fit for purpose, that the legal bar for harm inflicted by defamation is too low, and that courtrooms are not the place to settle matters of historical controversy. Be all that as it may, trials like this one perform a valuable service when they do occur—not for what they tell us about history (which is very little), but for what they tell us about those who falsify it.

Coincidentally, while Penny Marshall and Ian Williams were fighting their libel battle with LM in Court 14, elsewhere in the High Courts of Justice, David Irving was waging his own with the historian Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books. Lipstadt had described Irving as a Holocaust denier and accused him of malpractice in her book Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. Irving sued and, less than a month after the LM–ITN verdict, he lost. Lipstadt prevailed because, unlike LM, she was able to demonstrate that Irving had wilfully distorted the facts. Invited to compare the two verdicts at the time, Claire Fox responded that it was ITN who should be likened to David Irving since both had used litigation to try to silence their critics.

Needless to say, the similarities between LM and Irving are more important, not to mention obvious. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus (false in one thing, false in all things) is the preferred fallacy of the conspiracy theorist, who asks us to focus on a perceived vulnerability or inconsistency in an established narrative and then insists that this flaw contaminates and invalidates everything else. While LM’s defence laboured over Trnopolje’s barbed wire fence, David Irving was arguing (incorrectly) that there were no holes in the ruined ceilings of the gas chambers through which Zyklon B pellets could have been safely introduced. “No holes,” Irving confidently informed the court, “No Holocaust.”

For all its imperfections, a courtroom trial does provide a controlled environment in which the extravagant claims made by conspiracists and revisionists can be cross-examined under oath, stripped of the rhetorical bombast so useful to demagogues in a chaotic public square. And, in both cases, their counter-narratives dissolved under scrutiny because sustaining a defence of those accused of inflicting terrible human suffering required the wilful and systematic misrepresentation of evidence.

Today, Thomas Deichmann’s article survives on crank conspiracy sites and Serbian nationalist propaganda outlets, which is where it belongs. In 2000, LM’s allegations became the basis for a Serbian propaganda film entitled Judgement! made by Jared Israel, an American conspiracy theorist and at that time co-chair of the Committee to Defend Slobodan Milošević. “ITN,” Israel says in the film’s YouTube description, “had seen that Trnopolje was a humanitarian refugee centre.” This lie is now an important part of the Serbian persecution narrative—a poisonous false grievance, still used to kindle ethnic bitterness and resentment.

Fifty thousand Muslims lived peacefully in the Prijedor municipality before the war. By the time it was over, only 6,000 remained, the rest having fled or been murdered. The Croat pre-war population of 6,000 had been cut in half. Between 1992 and 1995, the Bosnian war claimed over 100,000 lives in total. According to the Research and Documentation Centre in Sarajevo, about 81 percent of the 38,239 civilians killed during the war were Bosnian Muslims. The bodies of many of these men, women, and children have been recovered from mass graves, some of which yielded hundreds of victims. In Srebrenica, as of 28 June 2019, the International Commission for Missing Persons had identified 6,982 of the roughly 8000 people reported missing after the massacre. And copious testimony at The Hague reaffirmed that, far from exaggerating the horrors of Trnopolje and Omarska, the ITN reports had cautiously underestimated it.

The evidence has been in for years: LM was as wrong about Bosnia as Herman and Chomsky were about Cambodia. As the writer and researcher Paul Bogdanor has observed of the latter’s genocide denial:

Anyone who reads the chapter on Cambodia [in Herman and Chomsky’s 1979 book After the Cataclysm] would be led to believe that the Khmer Rouge had done little wrong and quite a lot of good in Cambodia, and had been maliciously slandered by the Western media. The simple fact is C & H got it wrong and did so because they demanded absolute standards of proof from those like Ponchaud who had evidence of massacres by the Khmer Rouge, while their own notion that the media was being used for “imperialist” ends required no firm evidence at all. The evidence was made to fit preconceived ideas.

Neither Chomsky nor Herman ever acknowledged the enormity of their errors on Cambodia. And few of those who denied the Bosnian genocide have come to terms with the seriousness of their mistake, either. Ten years after the trial, Hume was still complaining bitterly about what a disgrace to free speech and justice the whole affair had been. When Ratko Mladić, the Bosnian Serb commander responsible for the Srebrenica massacre and the shelling of Sarajevo, was finally arrested in 2011, Hume was still haggling over the number of dead in Spiked. “There is no doubt,” he allowed, “that Bosnian Muslims were murdered at Srebrenica. But as has been argued before on Spiked, everything from the numbers involved to the circumstances of their deaths is far more open to question than the standard version of the parable might suggest.”

As of this writing, Mick Hume’s Facebook profile photo shows him with his wife on the steps of the High Court, as though this were his finest hour. Hume, and those of his former associates who continue to defend Deichmann’s essay and LM’s broader record on Bosnia, are almost certainly beyond persuasion now. The more someone invests in a lie, the more painful it becomes to renounce. But it remains a lie even so.

References:

18 Trial transcript, Day 4 AM, p 53

19 Trial transcript, Day 5 AM, p 39

20 Trial transcript, Day 7 PM, pp 66–67

21 Trial transcript, Day 4 PM, p 57

22 Trial transcript, Day 3 PM, p 48

23 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 11

24 Trial transcript, Day 8 PM, pp 54–56

25 Editorial “First Casualty?” by Mick Hume, LM, February 1997, p 5

26 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 28

27 Ibid. p 54

28 Ibid. p 55

29 Ibid. pp 90–91

30 Ibid. p 84

31 Ibid. p 91

32 “Evading the Charges” by Mick Hume (under the alias “Eddie Veale”), LM March 1997, p 18

33 “The Picture that Fooled the World” by Thomas Deichmann, LM February 1997, p 28

34 Trial transcript, Day 9, p 2

35 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 20

36 Trial transcript, Day 9, p 2

37 “Spare Any Change, Guv?” by Mick Hume, the Times, March 17th, 2000

38 Trial transcript, Day 7 AM, p 3

39 Ibid. pp 9–17

40 Ibid. pp 17

41 Trial transcript, Day 2 PM, p 64

42 Trial transcript, Day 8 PM, p 48

43 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 42

44 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 43

45 Ibid. p 29

46 Ibid. pp 29–30

47 “Atrocity, Memory, Photography: Imaging the Concentration Camps of Bosnia – The Case of ITN versus Living Marxism, Part 2,” Journal of Human Rights Vol. 1, No. 2, June 2002, p 144

48 Ibid. p 153

49 Ibid. p 155

50 Editorial “First Casualty?” by Mick Hume, LM February 1997, p 5

51 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 32

52 “The Picture that Fooled the World,” by Thomas Deichmann, LM February 1997, p 26

53 Ibid. p 31

54 Trial transcript, Day 8 PM, p 63

55 Trial transcript, Day 8 AM, p 36

56 Trial transcript, Day 8 PM, p 65

57 Trial transcript, Day 10 PM, p 62