Art

Coming Together to Honor a Dead Rock Star—And Ward Off Our Own Demons

In the months leading up to the news, I was in a bad place. Nothing in life felt right, and every day was a fight against hopelessness—to the point that even when good things happened, I would remain afraid or numb.

In May, 2018, Scott Hutchison, singer/songwriter/guitarist for the indie rock band Frightened Rabbit was found dead on the banks of Scotland’s Firth of Forth after having gone missing a day earlier. The final dispatches from his Twitter account indicated that this was not an accident or a case of misadventure. His suicide cut to the heart of the band’s fan community, a refuge for people struggling with mental illness, substance abuse and heartbreak. Scott’s songwriting delved deep into the dirty facts of living, but was also marked by a tender optimism housed within an envelope of pain. Scott’s disappearance and then death caused fans to ask: What does this mean? If he couldn’t save himself through his music, how can it help the rest of us?

In the months leading up to the news, I was in a bad place. Nothing in life felt right, and every day was a fight against hopelessness—to the point that even when good things happened, I would remain afraid or numb.

During a visit to Montreal, I walked from Mile End down to the old port, seeking to shed what I was feeling through physical exertion. It didn’t help. And looking out at the Saint Lawrence River, not for the first time in life, I began to think: “What if I just…?” The moment didn’t come to anything. I went for dinner and had drinks instead, and then walked back. But that night I dreamt I was planning and then attending my own funeral.

Shortly after I got back to Toronto, I heard the news about Scott Hutchison. It’s no exaggeration to say that it could have been me. We were about the same age, and shared similar artistic ambitions. It was hard to hear that someone who made beautiful music, and was successful at it, who said things that resonated as true for me and many others, had given up on living. If Scott lost that battle, what hope was there for the rest of us?

The tragic phenomenon of the copycat suicide is well known to mental-health professionals. But suicides of famous people also can spur a different reaction, as was the case with me. I immediately made an appointment with my doctor, and returned to drug therapy. I quit drinking (temporarily, as it turned out), and doubled down on doing the “right things,” like exercise and healthy eating. I’d recently lost access to a psychiatrist I’d been seeing semi-monthly for several years, but was able to get on another clinic’s referral list.

Did things improve? A bit. But much of the time, it feels like clinging onto a descending rope, trying to climb up while the rope itself keeps spooling downward. When certain familiar stresses assert themselves, I feel as though I might lose my grip completely. By the time my birthday rolled around last fall, I found myself again on a shoreline, this time it was northern Lake Huron, in tears, wondering what on earth it would take to keep the dark thoughts away.

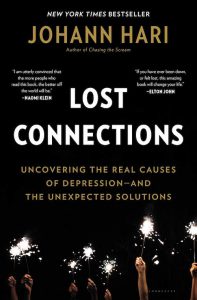

It’s no secret that rates of depression and anxiety have increased enormously in recent years. We also are observing a high death toll from opioids, which many victims are using to numb emotional pain as much as physical symptoms. There appears to be something in the way we are living that may be fundamentally bad for us—not morally, but perhaps spiritually. In his 2018 book Lost Connections, Swiss-British writer Johann Hari theorized that though this crisis is multifaceted, much of it appears rooted in a loss of our sense of meaning and community. His previous book, focusing on the war on drugs, concluded that the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety, but connection. In his new book, he extends that argument further to include depression. This absence of connection has been widely discussed since the appearance of Robert Putnam’s 2001 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. But there is a new focus on this phenomenon as a matter of public health, not just sociology. Loneliness is literally killing people.

There is a political aspect to this phenomenon, too. As Jeffrey Quackenbush recently wrote in Quillette, social media barrages us with “a litany of agitation or exhilaration: Trump, Brexit, Populism, Impeachment, Social Media, Social Justice Warriors, #MeToo, Alt-Right, Troll Farms, the Death of Journalism, the Rise of Authoritarianism, Fake News, ISIS.” New forms of news consumption encourage each of us to inhabit virtual silos—which has the effect of downgrading the healthier connections that exist within everyday life while using the cheaper fix as an outlet. We end up consumed by the search for immediate gratification in a fake digital universe. The parallel with drug addiction is obvious. And quite like drug addiction, as we live less in our real lives, we move further into a void that fails to address our difficulties at any meaningful level.

In my case, however, digital culture wasn’t the true source of the problem. I’ve been afflicted by bouts of darkness for nearly as long as I can remember—going all the way back to grade school. Some periods were worse than others. But in recent years, the problem has felt more constant and intractable. Instead of having a bad month or three on different parts of the calendar, or a year here and there, these periods started to extend themselves until they touched. Times of relief became rare. In 2017, I was shocked by a cancer scare that required urgent surgery, which was very much in my mind when I felt those dark thoughts in Montreal. Sometimes, a brush with mortality inspires a person to live life to the fullest. But in my case, it had mostly the opposite effect. Given my uncertain career (I work in the arts), dwindling youth, stressed finances, and shrinking options, it was hard not to see the incident as just another sign that life is on the downswing.

I could speculate endlessly on why this is my lot in life. Bad choices and bad luck no doubt have much to do with it, along with experiences. But mental-health outcomes also have a strong genetic aspect. One of my parents has been severely afflicted—to an extent I didn’t quite realize until a disturbing phone call I got in the middle of the night about a decade ago. There were earlier incidents, too, when it was clear something was very off—though it was not openly discussed. I struggle with what I may have taken from this. It’s hard for me to be honest about how I feel at times, especially with those to whom I am closest. Some of this is because of a sense that I shouldn’t feel as I do, that I have no right to it, a feeling that is accompanied by a lot of guilt. But silence and guilt metastasize into additional fuel for a constant feeling of impending disaster. My family member has found a strategy that works, and is now in a good place from what I can tell. I hope to find a similarly successful strategy for myself.

One challenge is that many of the easiest coping strategies just make depression worse in the long run. It’s tempting to go online and read the latest Twitter arguments, the latest cultural-war controversy, the latest scandal. All of it allows one to temporarily externalize inner pain into outrage at someone else—which, in my worst moments, became more tempting to do as a balm for unarticulated frustration, anger and sadness. But when you wake up the next day, you still have the pain—plus all that outrage—buzzing about in your skull.

Earlier this year, I attended a memorial listening party in remembrance of Scott Hutchison on the one-year anniversary of his death. It was organized by a friend of mine and his partner here in Toronto. But thanks to an active Facebook group based around the band’s fans, it attracted visitors from as far away as Wisconsin and San Diego. Several fans even wandered in off the street when they saw the sign outside the venue. There were shot glasses that someone had printed in homage to the 2008 Frightened Rabbit classic Head Rolls Off, a song that offers musings about the need to “make tiny changes to earth,” and postcards featuring some of Scott’s art. Frightened Rabbit concert footage played on a big screen, followed by an endless playlist run through the bar’s soundboard.

I was nervous, and felt a bit out of place among this group of die-hards. Though I’ve been a fan of the band for years, the Facebook group was new to me. In the months since I’ve joined, though, I’ve been struck by how much time people spend in the group simply comforting each other—telling their stories and talking about what they can’t make sense of in their lives, and looking for ways to connect through doing it.

In the end, I didn’t eat enough, drank too much, and showed myself out a little later than perhaps was wise. But I also met a guy from the UK named Brian who told me about his struggles with social anxiety that emerged out of the death of an older sibling when he was a kid. It was a rare conversation to have with a stranger. In fact, Brian told me he almost never speaks to anyone about it. When he left, he hugged me hard. It seemed like some small bit of weight he was holding had lifted.

The next day, I woke up with the dread feeling in my chest again, and the thought that I didn’t want to be here anymore. I tried to do the stuff I’ve been learning in cognitive behavioral therapy, about placing those thoughts somewhere where they aren’t accepted as “truth.” Maybe I felt this way because I’d had too much to drink. But the unfortunate fact is that there are times when, in spite of the medication, therapy, new friends and minor career opportunities, I still often feel frozen, trapped, afraid and alone. Alcohol and depression often go together because the booze kills dread and drowns sadness, and allows for rare moments where you feel like you can live without the toxic noise in your mind. But of course, it comes with its own potential for life-ruining toxicity.

There’s no single thing that will save me. And even the mixture of partial solutions always feels like a work in progress. But the way that Frightened Rabbit fans have created a healthy community that allows them to connect and find comfort in their struggles (without competitively pursuing recognition of their victimhood) is unusual and valuable. It won’t become my magic bullet. Nothing will. But it will help.

We all need to grasp what’s available and good in life a little tighter, instead of retreating into internet opium and other addictions. Continuing to “make tiny changes,” and working to have faith that things can and will get better, is an approach that admittedly can feel hard and endless. The main consolation is that the only real alternative is much, much worse.