Recommended

Bukowski: Recommended Reading for the Damned

Were he still alive, he most certainly would not meet the demands of today’s “sensitivity readers,” nor those imbedded in the big publishing houses who scan a writer’s work for transgressions, nor those on social media who do the same with a writer’s personal life.

There is enough treachery, hatred, violence,

Absurdity in the average human being

To supply any given army on any given day.

So begins one of Charles Bukowski’s most iconic poems, “The Genius of the Crowd.” Even though it was first published in 1966, it seems particularly poignant in our era of outrage.

BEWARE THE PREACHERS

Beware The Knowers.

[…]

BEWARE Those Quick To Censure:

They Are Afraid Of What They Do

Not Know

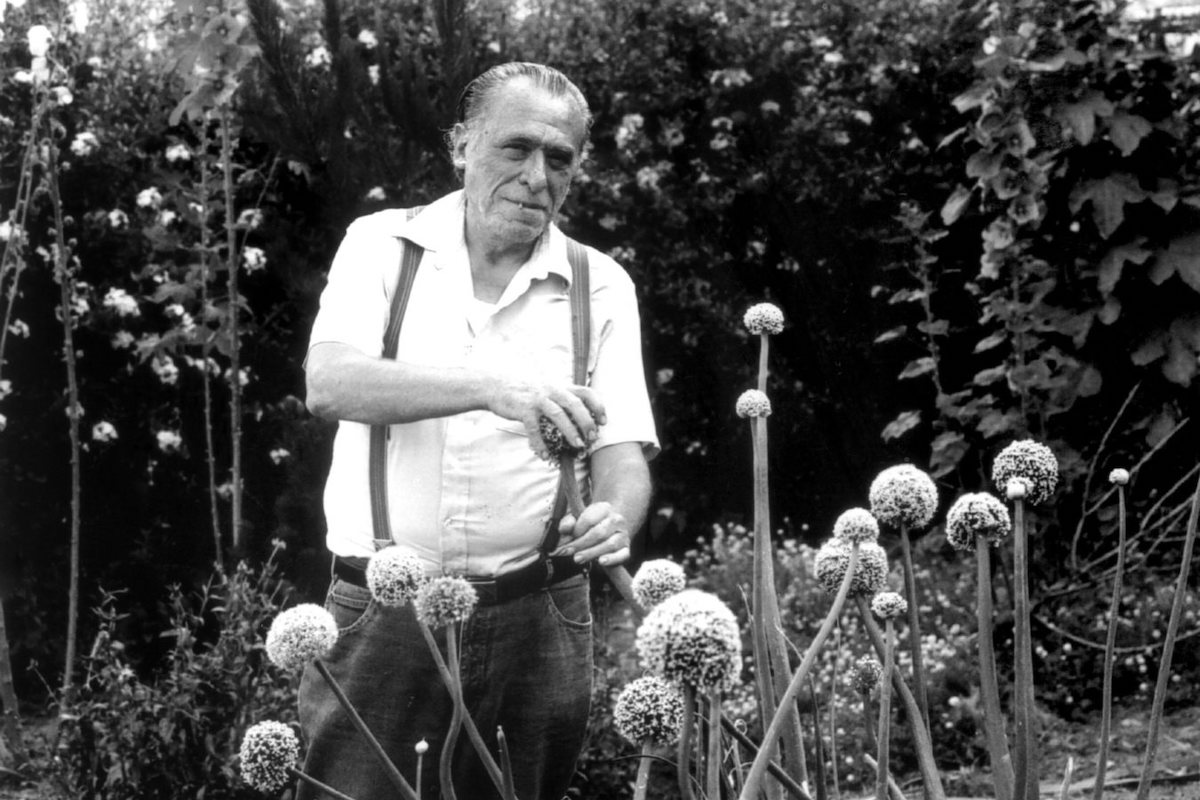

Bukowski, born in 1920 in Andernach, Germany to a German-American father and German mother, moved to Los Angeles when he was two years old and would live there for the rest of his life. Although his novel Ham on Rye, an autobiographical account of his abusive childhood, is an American masterpiece, and his short story, “The Most Beautiful Woman in Town,” a sad tale about a woman who gashes her face to make herself less beautiful, is comparable to anything Hemingway or Cheever wrote, it was in poetry where Bukowski’s strength really lay.

Bukowski died 25 years ago. Were he still alive, he most certainly would not meet the demands of today’s “sensitivity readers,” nor those imbedded in the big publishing houses who scan a writer’s work for transgressions, nor those on social media who do the same with a writer’s personal life. Nor would he meet the demands of today’s small press poetry magazine mission statements, which not only require a poet to be talented, but to also be a morally exemplary person.

Then again, Bukowski never was a model citizen of the poetry community, or any other community for that matter. He was a misfit and an outlaw. Unlike many contemporary poets, he never completed college and didn’t take a job in academia—instead, he worked in a post office for 15 years before quitting to write full time. He also drank a lot. And he could be violent and abusive. Ardent fans who saw John Dulligan’s 2003 documentary Born into This (or the original interviews Barbet Schroeder conducted with Bukowski in the early eighties, on which Dulligan draws) and were not appalled by the scene in which a belligerent Bukowski lunges at Linda Lee Beighle (whom he’d marry a few years later), calling her a “whore,” might need to reassess their cultish fandom. Of course, a great artist can be both angel and devil, both sinner and saint. A great artist is often a contradiction and many are prone to bad behavior. Ginsberg advocated pederasty. Mailer stabbed his wife. Burroughs shot his. Anne Sexton allegedly subjected her daughter to sexual abuse. Whitman was a defender of eugenics-based racism. Céline, T.S. Eliot, and Amiri Baraka were all antisemites. Often a great artist is a contradictory figure, both creative and destructive, both loving and hateful. And Bukowski was no exception.

I suppose he could have forbidden Barbet Schroeder—who also directed Bukowski’s semi-autobiographical screenplay for the 1987 film Barfly starring Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway—from ever releasing the interview tape, but that wasn’t Bukowski’s style. He didn’t hide his warts and he didn’t hide his wars, especially those inner ones.

“The problem with Bukowski,” says Timothy Green, editor of Rattle poetry magazine, “is that he’s not just a writer, but a lifestyle for a lot of his fans, and an excuse to be abusive. A great poet, but I don’t like the way he’s often used. It’s one thing to appreciate the poems of a convicted murderer but it’s another thing to use that as an excuse to go kill people.” “Hard Pass,” tweeted poet Kaveh Akbar—one of the most widely celebrated young American poets of our moment—about Bukowski recently.

Other young and particularly male poets, even if they do like him, aren’t especially eager to say so publicly out of fear of being labeled a “broet,” which is as derogatory as it sounds and means exactly what you think it does, even though this is a gross mischaracterization of Bukowski’s work. Bukowski was never a “bro” and despised overt displays of hyper-masculinity.

It’s true, of course, that his (mostly male) lifestyle imitators can be annoying and maybe it’s not a bad thing that most of them disappear, often only imitating his drinking habits while ignoring his deep compassion for humanity, or sense of humor, or work ethic, or extensive cultural knowledge of the literary, artistic, and classical music worlds. Because if there is anything Bukowski writes about more than drinking or women, it’s art: other writers, painters, and composers. It was from Bukowski that, as a young man, I learned about so many important writers from Carson McCullers to Sherwood Anderson to John Fante, from Dostoevsky to Céline to Sartre, D.H. Lawrence to Knut Hamsun to Catullus. It was from Bukowski that I received a literary education far greater than anything I’d get in college, majoring in comparative literature.

Of course, in college, nobody talked about Bukowski. The professors scoffed at the mention of his name. But, generally, he wasn’t even mentioned. He wasn’t dissertation worthy. He was a lowlife. Uneducated. And his words were simplistic, easy to understand, so there wasn’t much to excavate. The dislike was mutual. “Buk hated academia,” says longtime friend and fan of Bukowski’s, Joan Jobe Smith, poet and editor of Pearl and The Bukowski Review. “[He] called them ‘in-bred snobs.’”

I ask Smith why we should still read Bukowski. “His voice,” she replies. “His vernacular. His existential grit, been there-done-that human comedies and tragedies, told boldly, sometimes brazenly. His old wise man wit: world weary and wary. I love his depictions of time and place and his love of my L.A. He writes about women more than any male writer I can think of. Women who are his heroines or distressed goddesses or kick-butt beauties and hot mamas who get the last laugh. But yes, dear young feminists today: I know, I know: not all is paradisal poesy and prose of praiseworthy palaver while reading the bombastic, sometimes dirty rotten s.o.b. Bukowski…”

Was he a misogynist? “Not at all,” says Smith. “The times he does exhibit misogyny in his writings it’s pure b.s. and wishful thinking. The real women in his life—his women that I became friends with—gave him ten times more hell than he ever gave them.”

It was Bukowski who encouraged Smith to write her true-life experience as an inexperienced young writer in the 1970s. Smith had been a go-go dancer on the Sunset Strip in the late 1960s and early 1970s but had been discouraged from writing about it by her male university professors.

“Though my conservative academic mentors slut-shamed me (as it’s called today), thought my bikini-clad, dancing go-go girl life prior to going back to college ‘tawdry’ and best kept a secret and insisted I write about something else, more respectable and more acceptable, Bukowski applauded my courage to have done what I did for 7 long, hard-working years (1965-1972). My academic mentors, when they’d first read the go-go tales, thought my first-person narrative a literary device and were shocked to know that it was not fiction but all true. Whereas, been-there, done-that former barfly Bukowski encouraged my first-person tell-it-like-it-was voice—because he, too, an outsider, had walked on the wild side.”

It’s this interplay between that first-person-tell-it-like-it-is-voice and a fictional persona that sometimes confuses people about Bukowski, and leads to a fixation on the man himself, often overshadowing the work, some 25 years after his death.

“Bukowski, privately, in his personal, platonic relationship with me was the same man as the Poet Man who wrote his poems,” says Smith. “He lived what he wrote. He wrote the truth—his Truth, that is, according to him. And he was insightful, intelligent and had a great sense of humor. He loved to laugh and made you laugh with him.”

What is fiction and what is autobiography when it comes to Bukowski? What is persona and who is the real man? Sometimes the author of a tender poem like “The Bluebird” gives way to the drunken, badly behaved bard and confusion abounds. Perhaps the “real” Bukowski was both of these things—the conflicted, sometimes abusive man, but also the compassionate and honest writer full of empathy for the downtrodden and forgotten. Though he bragged that he liked to make himself the hero in his writing, he never really did. He was more like the court jester. The joyful mischief maker. The provocateur. Always pivoting himself between the fool and the wise old sage. Often, instead of making his narrator a hero, the joke is on him. And, like the court jester, Bukowski was there to entertain. Which often meant making us laugh even when it’s at his (or his character’s) expense. This is something his joyless critics seem to miss.

A couple months ago, David Orr, in a review of the latest posthumous Bukowski publication for the New York Times, would take the opportunity not to review the artistic merit of Bukowski’s work, but to pen a diatribe about the author’s bad behavior: “It’s interesting to go through On Drinking and note the many things that Bukowski either omits or wants the reader to avoid thinking about.”

In the not-so-ambiguously titled article, “What Charles Bukowski’s Glamorous Displays of Alcoholism Left Out,” Orr takes particular issue with the poem “night school,” which is set in a “drinking driver improvement school.” Though certainly not one of Bukowski’s strongest poems, Orr seems to question the behavior of the speaker, who leaves the class on a break to go have a beer and comes back to find he’s the only one who scored 100% on a test everyone takes to check if they’ve been listening to the instructor. “I am the class intellectual,” the speaker jokes. This is Bukowski at his most sardonic. But this kind of black humor clearly doesn’t appeal to Orr who prefers to play inquisitor:

Why was he in that class? Did he hurt anyone? Did he kill anyone? This is one of several times that Bukowski talks about plowing around hammered in a car, yet every episode carefully avoids any sense of the possible horrific consequences for other people…

And if that weren’t bad enough, Orr adds another platitude: “…people think about drunken driving much differently in 2019 than in 1981 when ‘night school’ was published.” By the end of the article I’m not sure if I’m reading a review of Bukowski’s work or a public service announcement about the perils of drunk driving. Is this written by a literary critic or a member of M.A.D.D.?

“There’s a problem with the way we idolise drunk male writers,” is the subtitle of another review, written by Ceri Radford for the Independent and published a few weeks later. Like Orr, she has trouble keeping Bukowski’s fictional characters separate from the man himself. But she also doesn’t seem to have read much of Bukowski’s work beyond the excerpts in the book she’s reviewing. She doesn’t question the wisdom of the publisher or the author’s estate for trying to make a buck by repackaging these excerpts under such a gimmicky title. Instead, like Orr, she chooses to scold Bukowski for his personal misbehavior, while warning readers about the health consequences of drinking: “Though he lived to be 73, a lot of other people who drink, don’t.”

It seems to me that some of Bukowski’s critics could use a drink. I dread a future in which our artists must meet the high moral standards of a David Orr and Ceri Radford. How boring the future of fiction or poetry will be when its value depends upon the rectitude and responsibility of its author. Or has it already come to that? Could a Bukowski be published today? Not likely. What goes missing then is the chance to glimpse the darker and messier side of life, which is still there no matter how many “sensitivity readers” try to edit it out, and no matter how many Twitter mobs try to suppress it.

What is perhaps even more alarming about these reviews is the insinuation that art is something to be feared because it can influence people to do bad things. How is it Bukowski’s fault that some people become alcoholics? That’s quite a responsibility for a man who couldn’t even control his own drinking. Not to mention the familiar assumption—such a common narrative of our day—that readers need to be protected by those who know better. When art is framed by fear and moral grandstanding, it always leads to censorship. Today, of course, it isn’t so much a religious concern about obscenity that drives censorship and informs taboos, but deviation from politically correct orthodoxies.

In an article for Reason magazine entitled “Cancel Culture Comes for Counterculture Comics,” Brian Doherty writes about the recent attempts to send comic illustrator Robert Crumb down the memory hole, and the problem of what Doherty calls the “social justice re-evaluation of artists”:

…Appreciating a creator isn’t—or needn’t be—a matter of being “down with” the actions portrayed in his every work. One of the many reasons humans have art is to understand, play with, portray, question, and explore the human condition…Portraying darkness and evil in art is not the same as celebrating darkness and evil, even when the depiction is not safely anchored to a clear statement of the artist’s anti-evil sympathies. Offense and transgression can be a vital part of how expression stays lively, fresh, startling, moving, and true to the human condition. That transgressive art is hard to defend in sober, sensible ways is precisely the point.

It’s no coincidence that Crumb has illustrated the covers for three of Bukowski’s books. Both artists use humor and satire to explore the grittier side of the human condition. Like Crumb, Bukowski’s artistic transgressions are not meant to be a celebration of decadence or evil, but rather a mirror held up to humanity—a reflection that makes many uncomfortable. Bukowski didn’t just give us the pleasant parts of the human condition. He refused to put a shine on what he saw. He poked around in those dark corners. He emphasized the “condition” part, as if it were a sickness:

if we take what we can see—

the engines driving us mad,

lovers finally hating;

this fish in the market

staring upwards in our minds;

flowers rotting; flies web-caught…

These things, and others, in content

show life swinging on a rotten axis.

At the same time, Bukowski doesn’t just despair, but celebrates what he can:

But they’ve left us a bit of music

and a spiked show in the corner,

a jigger of scotch, a blue necktie,

a small volume of poems by Rimbaud,

a horse running as if the devil were

twisting his tail…

Orr argues that, although Bukowski lived a “life much darker and hungrier and more desperate than that of most writers” he “paused at the black threshold and backed away.” On the contrary, Bukowski led his readers across precisely that threshold. His dark honesty isn’t bleak and it isn’t desperate. In fact, it is many of today’s poets who back away, whether in fear of themselves or in fear of revealing too much and receiving backlash within the community. One poet writes a lot about his sobriety, and often refers to the bad person he once was before getting sober, but never shows you any of it. Another writes a beautiful antiwar epic about resistance, but never questions the fragility of his own virtue, or the possibility that any fallible person may end up on the wrong side of history. Bukowski didn’t back away from the messiness of existence, he just doused it with Rabelaisian humor, inspired perhaps by Henry Miller’s description of “a world without hope but no despair.” For Bukowski, that world was both cruel and beautiful.

If he were alive today, he’d surely get a kick out of any attempts to cancel him or erase him or send him down the memory hole or whatever the latest phrase is that damns someone to hell. “Iconoclasts and literary phenomenons often exhibit bad behavior,” says Smith, when I mention how some young poets are turned off by those unsavory elements of his character. “To not read Bukowski today is a mistake.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article stated that Bukowski did not attend college. He attended Los Angeles City College briefly, but never earned a degree. Apologies for the error.