Art and Culture

Jordan Peterson, And the New Chivalry

Peterson could remain detached from the people who seek his help, but he is courageous enough to connect with their pain, and thereby render himself vulnerable in the public forum.

In his recent appearance at Liberty University, Jordan Peterson delivered this verdict on the dominant attitude toward masculinity among our society’s elites: “I don’t think we do a very good job at the moment of encouraging men. We have this idea that there’s something intrinsically oppressive about the patriarchy and about masculinity in general. And I think that’s nonsense. I think that strong, honest, truthful, courageous men pursuing noble goals is of great benefit to everyone, male and female alike.” Members of the student audience applauded loudly, little knowing that not 10 minutes later, a scene would unfold in which Peterson would have an opportunity to match action to words.

By now, tens of thousands of people have seen the clip of the desperate young man who slipped past security to rush the stage and appeal to Peterson for help. The high-definition video feed was cut, but amateur footage shows Peterson leaving his seat and following David Nasser, Liberty University’s Campus Pastor, to engage. Nasser assures the troubled boy that he is “in the right place,” telling security to stand down while he leads the audience in prayer. As the student collapses in sobs, Peterson can be seen kneeling down to put a calming hand on his heaving shoulders. After the student is escorted offstage, the video feed comes back up as Nasser and Peterson return to their seats. Peterson seems shaken and visibly moved to tears.

The whole vignette plays out in less than two minutes. Yet it affords an opportunity for reflection—by shedding light not only on the specific nature of Jordan Peterson’s appeal, but also on the larger question of what masculine virtue can and should look like in the modern age.

The student did not have a weapon, and was in no way a threat to either Nasser or Peterson. But neither man could have known that for certain. Despite the fact that Peterson’s public appearances have been the target of numerous violent threats (with one student at a Canadian protest being accused of carrying a garrote), both Peterson and Nasser moved toward the man, not away, adding an element of courage to their obvious compassion.

Numerous viewers across social media have been touched by Peterson’s immediate, evidently heartfelt concern for this young stranger’s well-being. Yet the response has not been completely positive. When I shared my report of the event on Facebook, one commenter said that he found Peterson’s intense emotional investment unappealing. As a fellow Canadian, he judged that Peterson had “forgotten his culture” and really ought to “bottle up the waterworks.” It’s one thing for the half-French Justin Trudeau to get misty-eyed mid-speech. But, he opined, men of good Anglo stock should remain stoical, even if they have to medicate their anxiety with a Scotch or two.

A pile-on ensued, in the course of which another commenter aptly quoted historian Andrew Roberts on Winston Churchill: “You should never see Winston Churchill as the buttoned-up, Victorian aristocrat of his age, class and background. He was instead a throwback to an earlier era. He was a regency figure, a romantic figure, somebody who was willing to wear his heart on his sleeve. In the course of the Second World War, there were no fewer than fifty times when he burst into tears in public. Fifty.”

The word “throwback” suits Peterson, too. For his appeal rests to no small extent on his image as a man out of time. Indeed, it is more than likely that he has already broken Churchill’s tear tally.

Peterson’s visibly manifested sorrow often is prompted by reflection on people who are lost, directionless and suffering. To adapt Dostoyevsky, Peterson is not concerned merely with “mankind in general,” but also with “man in particular”—with unique lost souls and the struggle to heal them. In one particularly wrenching Q & A in 2018, he reads off a question from a parent looking for advice after a daughter’s suicide. It’s a question that he says “cuts close to the bone,” as he tearfully opens up about his own family’s history with depression.

Does Peterson’s choice to channel the suffering of another soul make him less masculine, even in the traditional (some might say sexist) sense? I say no. As Ben Sixsmith has wisely observed here at Quillette, “Stoicism is a good thing that, like all good things, becomes damaging in excess.” Certainly, visible emotion is not a sine qua non of sincerely felt compassion, as David Nasser’s focused calm during the Liberty U episode demonstrates. Yet tears need not be taken as a sign of weakness. Peterson could remain detached from the people who seek his help, but he is courageous enough to connect with their pain, and thereby render himself vulnerable in the public forum.

Yet from the point of view of Peterson’s critics, it truly does seem that he is damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t. Cynics from the right will judge his tears as a betrayal of masculinity, while cynics from the left will dismiss them as calculated performance art.

* * *

To New York Times writer Nellie Bowles, Peterson appears as a man out of time in a far more sinister sense. In her eyes, he is an icon of toxic masculinity—a “custodian of the patriarchy,” as the Times headline writers put it. She reports that feminists consider Peterson’s philosophies to be “part of a bigger global backlash to gender equality progress.”

“It’s an old story, really,” says one of the various Peterson critics she quotes. “In a lot of nationalistic projects, women’s bodies and sexualities become important sites of focus and control.”

In rare instances, Peterson’s musings about men and women really do seem odd, and have attracted pushback even from otherwise friendly sources. In the Times interview, for instance, Peterson said that the killer who drove a van into crowds of people in Toronto last year “was angry at God because women were rejecting him…The cure for that is enforced monogamy. That’s actually why monogamy emerges.”

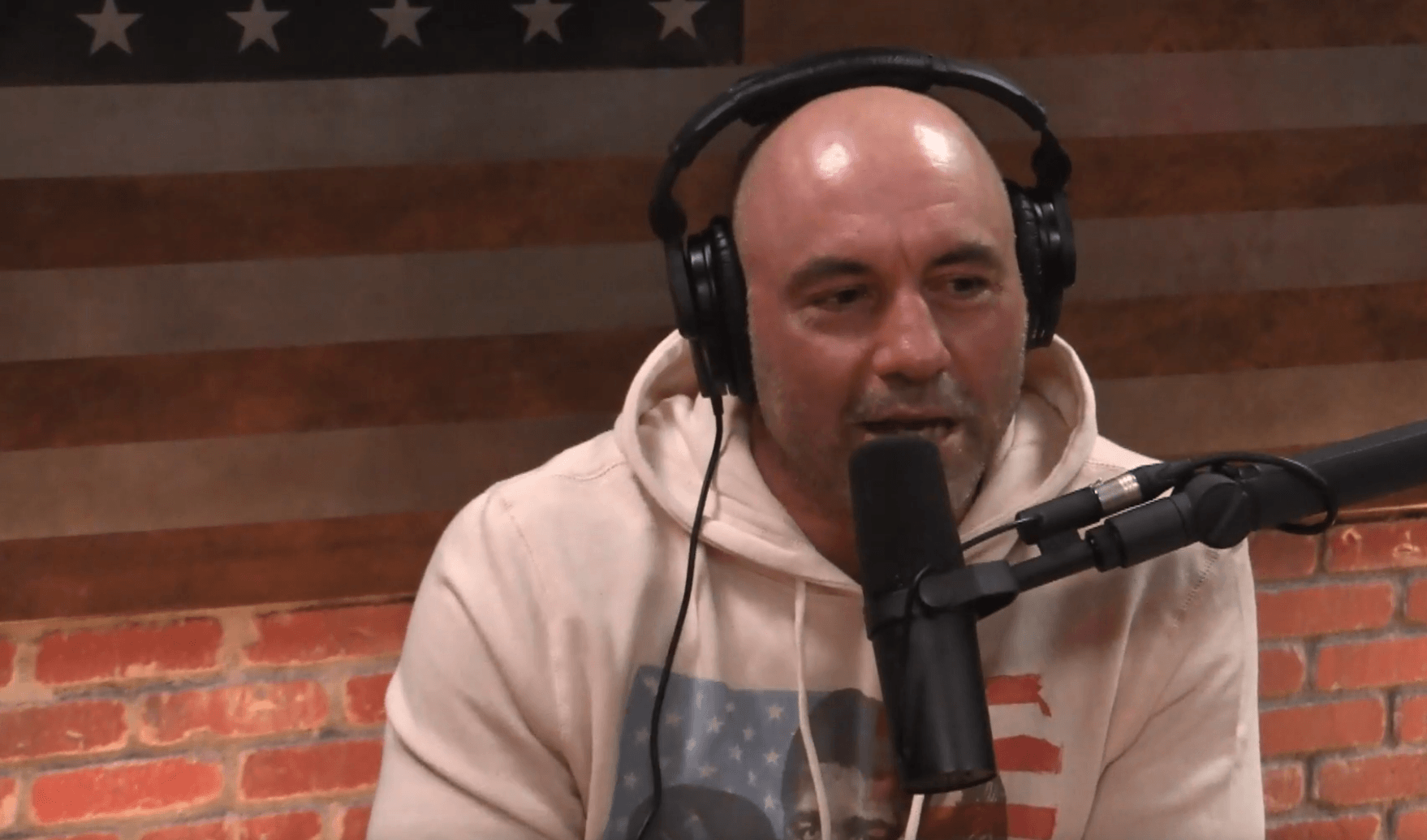

The idea here is that when alpha males monopolize the attentions of women, many men are left with no companionship at all. But even Joe Rogan noted that it is difficult to trace a through-line from the socially enforced approval of monogamous marriage to a solution for loneliness in all cases. Peterson laments that “nobody cares about the men who fail,” which seems true. Yet the idea that all failing men can be whipped into marriageable shape is naïve.

But the campaign against Peterson’s allegedly retrograde views on the sexes predates these comments, and seems more substantively rooted in his view that “traditional” gender roles are not mere social constructs. The idea that some women might be happier bearing children and homemaking than pursuing a career is a truth that dare not speak its name in public, even if many women confess it in private. In the past, Peterson has acted as counselor and life coach to Toronto lawyers, describing (in anonymized terms) how the women who’ve sought his advice often seem unhappy precisely because they’ve been taught to pursue a model of success copied from career-obsessed men. To many of us, this is simply good, common-sense advice. But to the sort of people who tend to write for The New York Times (or get interviewed by The New York Times), it’s often treated as heresy.

At the same time that Peterson allegedly hopes to confine women to the kitchen, he allegedly offers his male readers nothing but “mindless praise of hierarchical dominance,” as one liberal Catholic reviewer put it. Peterson issues a call to adventure and heroism, but we are warned it is only a “ ‘heroism’ of the Übermensch”—the Nietzschean strongman who contemptuously tramples the weak underfoot as he ascends the ladder of social hierarchy. Under Peterson’s teaching, young men allegedly will learn nothing of “solidarity with the sick, suffering, and poor.” As another unfavorable review sums up, “[I]n Peterson’s worldview, morality is about getting what you want.”

Peterson is indeed brutally honest that a man must be strong and resourceful in order to find his way in life, and that many men lack such strength and resources. As he explains in his appearance at Lafayette University, a shocking number of men are rejected even by the army on account of their low IQ. His unvarnished summing-up is that “There’s nothing for 10% of the population to do.” Yet this quote cannot be taken in isolation from what immediately follows: “If that doesn’t hurt you to hear, then you didn’t hear it properly.” Is this the language of the Übermensch, or a language that harkens back to the idea that fortunate men are bound by honor to offer aid to those less fortunate?

Because Peterson’s fan base often is casually described as a rabble of sycophantic male acolytes, his detractors act shocked when reality intrudes upon their alternative facts. In one particularly barbed report, New Zealand writer Cecile Meier expressed horror at the “baffling number of women” she observed among Peterson’s fans. Like Bowles, she wonders what sort of internalized misogyny must be at work. Unfortunately, Ms. Meier never allows us to hear from these women, who no doubt would protest the idea that their admiration is the product of some mindless reflex.

Of course, none of us can judge Peterson on any basis except his outward appearance and expression. The Jordan Peterson we feel we know is the public, professional self he has chosen for us to know. Yet while we may not be privy to his innermost thoughts, what public evidence we do have provides clues about his character.

During the convocation at Liberty University, David Nasser perceptively touched on one time-honored starting point for sizing up a man: observing how he treats his mother. He mentioned that he’d had the chance to dine with Peterson and his mother, in whose company Peterson turned into “a playful son.” This is consistent with Peterson’s own oft-expressed pride in being able to make his mother laugh. A tribute he penned for her 80thbirthday radiates admiration, easy warmth and natural affection: “I love my mother, and I like her, too.”

This affection extends not only to Peterson’s mother, but to his late mother-in-law, whose tragic mental deterioration brought the whole family together in a spirit of fortitude. He often praises the way her husband—Peterson’s father-in-law—“stepped up” to care for her, as best he could at his own advanced age. Peterson’s wife and her sister also rendered aid, applying their experience as palliative-care nurses. During a February speaking event in Melbourne, Australia, he could be heard openly weeping at the memory of how gently the dying woman was carried through her decline and finally to her deathbed.

If you look up “misogynist” in the dictionary, I am reasonably sure that “cries in public over death of mother-in-law” is not a featured attribute.

We can also glean something from Peterson’s interactions with his female fans. At an event in New Zealand, a teenaged YouTuber named Emmy Hucker films her encounter with Peterson in the VIP line. She introduces herself as “Emmy Hucker from YouTube,” mentioning that Peterson shared her popular video Why I Love Jordan Peterson. After briefly drawing a blank, he lights up: “Oh yes, I think I remember that. I do remember that. Yes, I think I’ve heard about you.” He extends an arm, and she gives him a full hug, briefly resting her head in girlish trust. With this man, she appears to instinctively feel safe. He inquires about her channel, responding with a delighted “You did?” when Hucker says she’d met a number of her 1,800-odd subscribers at the event. “That’s a small town you’re talking to,” he encourages her.

In a YouTube comment under another fan review, a woman recalls that she found herself unable to say anything at all when her moment came to meet Peterson at a lecture last Fall. But instead of going through the motions and pushing on to the next in line, Peterson slowed the pace to engage with her. He finally managed, with great effort, to get her to say her name and describe why she’d come. Only when he had ensured that she got her money’s worth did he pose for their picture and send her on.

The cynical observer might ask whether this modus operandi is reserved for sycophants. How would Peterson respond if a woman told him she hated his book? In fact, I found out the answer when just such an interaction unfolded on Twitter last Christmas. In a tweet from a now-deleted account, a woman said that 12 Rules for Life did nothing for her, that she was still depressed, and that she still hated life. Peterson responded, “I’m very sorry to hear that. I hope that you find your way forward. I hope that you find something sustaining.”

There’s a word for all this. It’s an old-fashioned word. That word is “chivalry.” We no longer use it much, because to use it is to suggest what we all know, whether we admit it or not: that there is indeed such a thing as distinctively masculine virtue. There also is such a thing as distinctively masculine grace, tenderly extended to the vulnerable and the fragile.

But for many of Peterson’s critics, this is not the measure of a virtuous man. By their lights, a man is virtuous only insofar as he is willing to signal adherence to the new orthodoxy of maleness and femaleness, by which the very idea of “maleness” or “femaleness” is deemed a tool of the patriarchy. By enshrining as unassailable fact the idea that men and women are interchangeable, they put chivalrous men of the old breed out of a job.

For the modern man who would be thought virtuous must see all with what Thomas Sowell calls “the vision of the anointed”—the relations of men and women, the ills of the city, the governing of the nation. There is no room for “the tragic vision,” which sees clearly that in this difficult life, we cannot always alleviate the suffering of the many. Sometimes, we can manage only to alleviate the suffering of one. Perhaps we cannot save mankind in general. But perhaps we can love man in particular. And perhaps, in the end, that is all a virtuous man’s conscience asks of him.

I close with one more story, courtesy of a UK fan who recently came forward on FaceBook. At an event in Manchester, England, Peterson was sitting with Dave Rubin, discussing the mytheme of the Tree of Life. But some detail about how the Tree looked in a particular rendition was slipping his mind, so he abandoned the thread and moved on. A few moments later, a young audience member in the front row stood up and began climbing directly onto the stage in front of Peterson. Unlike the student who rushed the stage at Liberty U, he was not in a state of crisis. But it seemed clear to the fan watching up close that, like himself, this stage climber was on the autistic spectrum. As he scrambled up, he held out his phone strangely, seeming to offer it to Peterson.

Security swooped in from either side, ready to take an arm apiece and drag the boy away. But at a word from Peterson, they paused. Leaning over, in a low tone that the FaceBook correspondent could not describe, Peterson whispered, “It’s fine. I understand. You were just trying to show me the tree.”

To cast down the proud and lift up the lowly. To do justly and love mercy. To walk boldly, yet humbly. Herein is the art of manliness.

May its practitioners increase.