Art

Conservatives Need to Start Taking Art Seriously

Because many conservative journals have given up on the subject of art entirely, one is tempted to ask what conservatives are seeking to actually conserve.

Conservatives, crack open some champagne and celebrate. A remarkable renewal of traditional painting and sculpture has taken place in the American art scene over the past 10 years. At last, a cultural movement has emerged that builds upon time-honored practices instead of deconstructing them. In cities all over the country, new atelier schools are teaching classic methods of sculpting, drawing and painting, giving students solid foundations in techniques dating to classical Greece. The art they produce is exquisitely made, and also unmistakably of this time.

This flourishing community of 21st-century representational painters and sculptors is deeply concerned with making—in the simplest possible formulation—“stuff that looks like stuff”: imaginative but realist paintings that point their audience toward traditional subjects and ideas, but with refreshingly novel conceptions. These artists are using the Western idioms of art-making praised by America’s founding fathers themselves—George Washington, John Adams, James Wilson and Thomas Paine. Washington collected paintings of the sublime American landscape before such paintings were considered credible art. Adams was enthusiastic about historical paintings. He also found delight in art that was edifying, even moralizing—a taste shared by both Wilson and Paine.

I hasten to add that the conservative art I am speaking of here isn’t bland Norman Rockwell-style Americana. Sex, violence and horror are sometimes the vehicles of narratives that reinforce conservative values. Bible stories of rape, slaughter and death—which inspired many of the great Renaissance painters whose work fills the traditional artistic canon—testify to God’s power to shape human destiny. The story of the crucifixion, in particular, is hardly a cheery tale, but it carries the heart of the Christian message of self-sacrifice and redemption.

During the late 20th century, conservative culture writers spent much of their time as a sort of opposition party, (rightly) criticizing the use of government funding to subsidize lousy public art, and calling out faddish avant-garde artists for poor taste. And this tradition continues to this day, Bruce Cole’s 2018 book, Art from the Swamp, for instance, focused on the disastrous failures of National Endowment for the Arts funding for bad and ugly public-art projects — a huge cedar sculpture that caused allergic reactions in the building where it was installed; a giant rusting steel wall that blocked a courtyard; the shooting of a dog as performance art. It is good to expose such miscarriages. But perhaps Cole might also have been able to propose, say, a new method of selecting federally subsidized art that satisfies more of us; or of encouraging private funding of memorials and other publicly displayed projects.

Iconoclasm is easy — even ISIS was good at it. What’s more difficult, and constructive, is to explain what art we like, and to address questions such as: Is there even such a thing as “conservative” art that doesn’t descend into sentimentalism or kitsch? And, to be fair, a few commentators truly have tried to offer the sort of ideas I am encouraging—such as Andrew Klavan, whose 2014 book, The Crisis in the Arts, argues for a conservative embrace of digital media as a means to end-run leftist control of the art world’s commanding heights. Fine Art Connoisseur and American Art Collector tend to favor traditional painters and sculptors who should appeal to conservatives. And The New Criterion publishes solid, worthwhile conservative commentary on all aspects of culture. But these are sparsely situated islands within a wider media sea.

Because many conservative journals have given up on the subject of art entirely, one is tempted to ask what conservatives are seeking to actually conserve. Are conservative interests purely fiscal and political? Do we care about high culture? If we do — and of course we do — why have we gone silent on the issue?

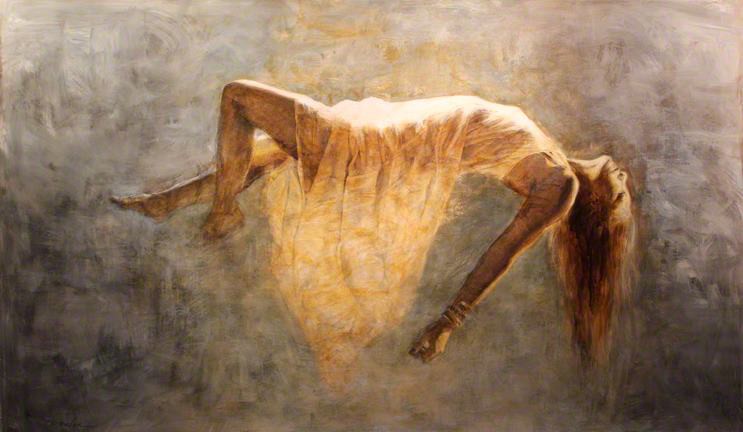

Many of the best new representational painters use allegory to share an ethical message, as with New York-based painter Adam Miller’s Twilight in Arcadia, presented at the top of this article. It is an unusual scene. Three hunters, a woman and two men armed with rifles, are intent on capturing their prey. Dressed in contemporary clothes, they are out of place in an idyllic woodland glade. Already at their mercy, a captured male faun lies prone beneath them and is held down by his hair in the grip of one of the men. In the background, unseen by the hunters, a female faun is restrained from running to her lover by two horned males, who know the danger is too great.

The huntress leads the party on to more targets, gesturing to the left of the canvas. Pure white geese and ducks scatter in the wind, frightened by the violence. The pastoral beauty of the pleasant landscape is broken. The dying faun pushes flowers into the barrel of a gun.

Faunus, the oldest of the Roman gods, was worshipped for centuries as representative of the energy of life that brought fertility to the world. The forest whispered his voice, and the land provided flowers, food, and shelter to mankind. He is the ancient life-force of the world, this atavistic god attacked by the destructive new forces of modernity.

To the artists and philosophers of the Renaissance, Arcadia was the unspoiled world, the Eden where primordial mankind (represented by the fauns in the painting) lived in a state of grace with God and nature—before the burden of knowledge of good and evil was inflicted upon us by Adam and Eve’s neglect. There, humans were noble savages, unspoiled by sin. The postmodern hunters threaten our longed-for return to that state of grace and attack the ideals of that ancient condition of harmony between God and man.

Although Miller’s exceptional technical work is traditional in style, the image could not be mistaken for a painting of any period of history except our own. It is absolutely 21st-Century, drawing influences from the imagery of science fiction and fantasy movies. We do not know Miller’s political persuasions, but his painting opens a discussion of ideas that are of tremendous importance and interest to conservative thinkers.

* * *

There was a wonderful meme doing the rounds of the internet a couple of years ago, informing us that “when Winston Churchill was asked to cut arts funding to support the war effort, he replied: ‘Then what are we fighting for?’” Alas, Churchill didn’t actually say any such thing, but it rang true, and millions liked and shared it, which suggests to me that rank-and-file conservatives recognize the preservation of our cultural heritage (and its expansion through inspiration provided by past masters) as a core motivator alongside the usual political fare.

If you’re a reader who has no specialized knowledge of the modern art scene, I invite you to examine some of the images that accompany this article and explore some of the many artists who exemplify the trends I am discussing here. (More can be found at The Representational Art Conferenceand the Art Renewal Center). If you are a writer, editor or publisher, I invite you to explore this subject in your own publications.

There is some urgency in this project. The cultural momentum that carried avant-gardism through the last century reached its apex a while ago, and the pendulum is now making a slow movement away from radicalism. There is a window of opportunity to create something new. This will be no revival of the Enlightenment or the Renaissance, since revivals never produce a repetition of their sources but always create new hybrids. Artists already are doing this of their own accord. With the support of enlightened philanthropists, curators, gallerists, collectors, academics and journalists, they can lead a remarkable new era in art that breaks new ground while paying homage to the Western tradition.