History

The Scars of Rwanda, 25 Years On

Dallaire, abandoned in hell, the commander unable to command, let alone protect, developed severe post-traumatic stress disorder.

I was home from University for the Easter holidays when the genocide began. April 7, 1994 is a date seared into my family’s psyche. My parents and I were transfixed by the news. They’d been front-line aid-workers for decades. My father was with the UN’s refugee agency. My mother, a child psychologist, worked with child soldiers. Neither were naïve about the world’s darker recesses, but the speed and scale of the savagery in Rwanda left everyone, even the most jaded and battle-hardened of my parents’ colleagues, reeling. The phone rang repeatedly. Meetings ran late. People we knew were dispatched to the region.

Over the next 100 days, an estimated 800,000 Tutsi were hacked to death with machetes wielded by their Hutu countrymen. House by house. Village by village. Town by town. Often it was neighbor killing neighbor. Occasionally, family members butchered their own kin.

Two pieces of footage from those days remain clear in my mind. One was shot clandestinely, by someone hiding in some bushes. It filmed a makeshift roadblock with a few Tutsi cowering on the ground as a mob of Hutu, high on bloodlust, circled and yawped and brayed triumphantly around them. As the axes rained down one of the men put his hands up, an instinctive yet hopeless bid to protect himself. His hands were shredded before his skull was split. The other was footage from a car as it drove down a residential street lined with bodies, one on top of the other, all bearing deep, angry axe wounds. It is hard, thirsty work, chopping up another human being, so often just a few strategic hacks were made and the person left to bleed out, in agony, sometimes for days.

The Hutu achieved a death-rate three times more rapid than that of the Nazis with their technologically advanced killing chambers. The extent of the planning that had gone into the genocide was immediately clear. Within hours of the President’s plane being shot down on the evening of April 6, senior Tutsis were being rounded up, the stockpiles of machetes released to the hounds, and a local radio station began broadcasting calls to massacre. Within about 12 hours the country’s political elite were either dead or in hiding.

In the months leading up to the slaughter, Romeo Dalliare, the Canadian General in charge of the hopelessly under-manned force of UN peacekeepers in the country at the time, had warned of this. A few months earlier, Dallaire had started to receive credible reports of killings around the country, and of children being raped and strangled. Then a well-placed informant had given him the precise details of how the genocide was to unfold. Where the weapons were being kept. Who was doing the training. Who was compiling lists of “cockroaches” to be eradicated.

The massacres were planned as a final solution to long-standing tensions between the Tutsi and Hutu, many of them exploited by the German and Belgian colonial authorities who deemed the Tutsi more racially advanced. In the late 1950s, the Hutu rose up against the Tutsi elite in a revolution which saw several hundred thousand Tutsi flee to neighbouring Uganda over the coming years. It was from here that Tutsi soldiers with the Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded Rwanda in 1990, sparking the civil war. Dallaire was sent there by the UN in August 1993 ostensibly to oversee a peace agreement. But it soon became clear that few had any faith in the deal. The preparations for the genocide gathered pace almost as soon as it was signed.

Dallaire said the gathering sense of menace was palpable, and he sent message after frantic, exasperated message to the UN Headquarters in New York, pleading for a mandate to raid the weapons caches and prevent the genocide from starting. The peacekeepers were in Rwanda under a Chapter 6 mandate which meant they couldn’t even use fire to stop a murder, only in self-defense if their own lives were in immediate danger.

The UN Secretary General at the time, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, had no interest in Dallaire’s SOS. Only a few years earlier, as Egypt’s foreign minister, he’d overseen an arms sale to Rwanda. Nor did the Ghanaian man in charge of Peacekeeping, the future Secretary General, Kofi Anan. Their response to Dallaire’s repeated pleas were always the same. No, No, No, and No Again. These are the kind of diplomats who intone “Never Again” whenever the Nazis’ genocidal project is commemorated. That being said, it is not unlikely that, had the peacekeepers intervened, armchair critics would simply have carped and sneered instead about “neo-colonialism,” Western interference, and the “white saviour” complex.

Within weeks of the genocide starting, the UN Security Council actually voted to remove the tiny peacekeeping force. Dallaire had asked for a few thousand extra troops to be sent so he could halt the massacres. Instead, he was ordered out and the UN presence was reduced from 2500 to 300. Incredulous, a few hundred soldiers, mainly from Ghana, Senegal, Tunisia, Bangladesh and Canada, Dallaire included, stayed.

By staying in an effort to protect civilian life, they were disobeying orders. The UN headquarters in New York actually cabled Dallaire to remind him that he had no mandate to protect people. Dallaire says he stood on the runway with tears of impotent rage streaming down his face, watching as the “international community” sent 1600 soldiers from Belgium, France, and the US to evacuate all foreigners and abandon the Tutsi to certain death. Sometimes this was done in the most callous way imaginable—the Rwandan colleagues of a Western diplomatic mission were ejected from a rescue vehicle as the genocidaires circled.

The peacekeepers couldn’t do anything by staying. They were so ill-equipped that when tens of thousands of people showed up, they didn’t even have tarpaulins with which to shelter them. They didn’t have adequate rations for themselves, let alone the people they were shielding. They struggled to find clean water as the country’s rivers and lakes became contaminated by dead bodies. The scant aid sent was farcically inadequate.

All they could do was set up a few tiny, safe havens—their Headquarters, a stadium, a hotel, and hospital in the capital, and a few others—and use their wits and courage to play an exceedingly dangerous game of bluff with the genocidaires. This required them to count on the mobs not knowing that the peacekeepers were unarmed, that they were not permitted to fight, that they did not have the authority to protect their prey, and that the world would not have cared had they been hacked up too.

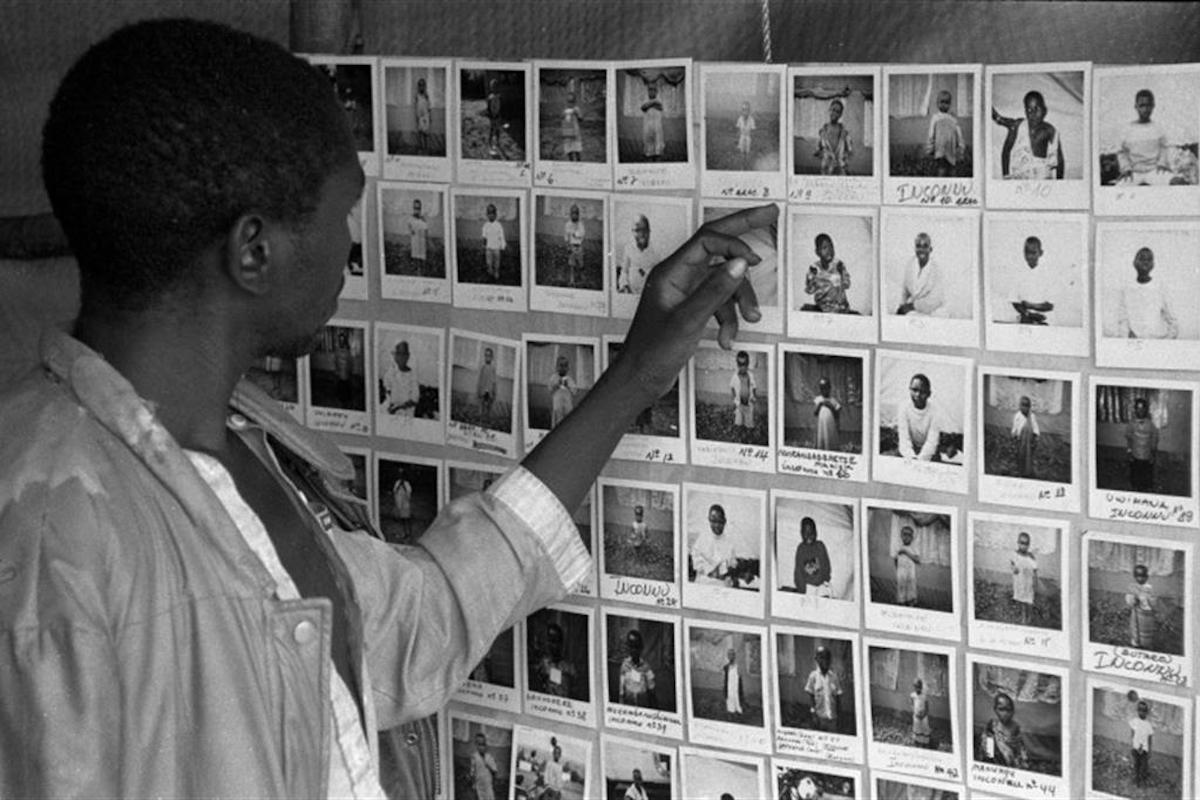

Conditions inside some of these havens became so awful that people were dying inside of disease whilst the killers waited for them outside. The Senegalese soldier, Captain Mbaye Diagne is personally credited with saving a few hundred people, including the children of the slain Prime Minister who he rescued from their hiding place. He used his considerable charm to smuggle people through checkpoints, hiding them under blankets and using jokes, cash, cigarettes and beers to ease them past suspicious militiamen. The peacekeepers only managed to save a few thousand people—a small victory as the bodies piled up in their thousands, then in their tens of thousands, and then in their hundreds of thousands. By the time it was over, 70 percent of the country’s Tutsi population lay dead.

All these men knew was that they couldn’t leave. And it mattered that they knew that—that those particular men did not fail as human beings when so many others did. The peacekeepers’ stand is one of the great acts of moral courage in history, and Dallaire was an exemplar of ethical conduct in the most terrible circumstances. Yet the personal cost of this stand, for many, was intolerably high. Captain Mbaye paid the ultimate price for his heroism and was killed at a checkpoint. Fifteen Peacekeepers died in total. Ten of them were Belgian soldiers tortured and murdered on the first day of the slaughter. The Interahamwe, the group orchestrating the killing, had calculated, correctly, that the murder of Western soldiers would be more likely to prompt Western countries to abandon Rwanda.

Dallaire, abandoned in hell, the commander unable to command, let alone protect, developed severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Towards the end he self-harmed, became reckless, driving maniacally through checkpoints at night, taunting death, storming up to the genocidaires, willing them to kill him. They describe it as a moral wound, a deep moral violation, this havoc done to a warrior’s psyche when they are not allowed to fight.

Back home in Canada, the ghosts of Rwanda began to follow him through his waking day. To sufferers of PTSD, the apparitions appear more real than anything else. They would surround Dallaire, touching him, reproaching him, the smell of their rotting corpses infecting the air he breathed, driving him insane. He understood, in his wretched despair, that he would never be free of Rwanda. Several years later, he finally broke and at his lowest ebb was found passed out drunk on a park bench, still convinced that the genocide had been his fault.

Dallaire was under no illusions about what he’d been up against in Rwanda. “I know there is a God,” he said. “Because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists and therefore I know there is a God.” Dallaire said that when he had to shake the hands of senior members of the Interahamwe they were cold like the hands of the demonic undead. Their eyes, he said, reflected a deeper evil than most people are willing or able to accept exists.

If the Devil had been loosed in Rwanda, then Dallaire and his men were the light that shines in the darkness, that the darkness does not understand.

* * *

My parents too were torn at by this evil. My father went to Rwanda in August of that year, as the slaughter was coming to an end. An army of Tutsi rebels had invaded from neighboring Uganda, systematically seizing land, stopping the massacres, and driving the Hutu out ahead of them. A tsunami of refugees, around two million people, now fled to what was then Zaire, since renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo. The men who carried out the genocide mingled among them.

My father’s refugee agency sent him to the area to help organize the aid effort. He came back six weeks later, vacant and shell-shocked. He would avoid questions about what he had seen, talking instead about the land, its beauty and lushness, its flora and fauna. Then one night, at about one in the morning, he woke and came down to the living room where I was still up watching TV. He poured himself a whisky, sat down and started talking, not really to me, rather in stream of consciousness, into the night. He had woken from a nightmare, as he did most nights, in which my sisters and I were being raped and murdered. Unfathomable numbers of women and girls had been gang-raped before they were hacked up. My father said their decomposing bodies littered the countryside. Corpses on their backs, leg spread, with rotting underwear still clinging to their ankles.

My mother went a few months later. The night she came back I stayed up with her into the early hours as she drank herself into a state of utter despair, recounting what she had seen. A visit to a church at Ntarama. About 5000 Tutsi men, women, and children had been hiding there when the gangs attacked, breaking the doors apart with grenades. The site has been cleaned up now, the skeletons picked of their flesh and neatly arranged for observation—an obligatory stop for genocide tourists. When my mother visited, the bodies still lay where they had fallen—a mass of entwined, agonized, putrefying corpses. She said the stench was detectable from a distance, the evil hanging like a thick, menacing fog.

The plight of two children. Both were about 12. Both now orphaned, their extended families butchered. The boy had a vast, gnarled scar at the base of his neck where the Interahamwe had tried to hack his head off. The girl’s face was split in two. She had taken a machete blow that had opened her skull without killing her. It had healed, but lopsided, with a deep ridge right across the middle. “She will have to live with that face all her life,” my mother sobbed. “Every time she looks at herself she will be reminded.” My mother returned to that girl’s plight again and again, over the course of that night as she got increasingly drunk, and over the long, drunken years that followed.

She made her first suicide bid a year later. She had got blind drunk and climbed into a small, manhole in the corner of our garden. One of my younger sisters found her when she woke in the middle of the night to mumbling and wailing from outside. She and my father pulled her out, naked and blathering and weeping. She vomited all over my sister as she emerged, crying about Marie. “Who is Marie?” my sister asked. “Marie!” my mother responded, irritated that my sister didn’t understand. “The girl in Rwanda! Marie!” My sister took the echo of “Marie” and the smell of her mother’s vomit into the exams she sat later that day.

My mother made her second suicide bid ten years later. None of the organisations my parents worked for offered any kind of psychological support to their employees, but the local, Swiss doctors who admitted her quickly diagnosed her with untreated post-traumatic stress disorder. This was the legacy she carried from Rwanda and all the other hellholes she had been working in—Sierra Leone and Liberia during the civil wars of the nineties, Ivory Coast, Bosnia. Treatment was arranged with a specialist psychotherapist who worked for the International Committee of the Red Cross.

* * *

Watching my mother unravel was terrifying. Amid a childhood of ongoing upheaval—from the age of two, my father’s job had seen the family move country every three to four years: England, Botswana, Zimbabwe, France, Switzerland, America, Turkey, back to Switzerland—my mother had been our only stable reference point. I tried everything I could to help and encourage her, but I only succeeded in getting pulled down with her.

People see my upbringing as akin to a permanent backpacking trip, full of positive multicultural, inter-racial exchange. A privileged “citizen of the world” upbringing to be envied by all. Glitzy. Glamorous. Jet-setting. I can count on the fingers of one hand the people who have ever come up with anything more nuanced when they hear about it. I got so fed up with these assumptions that I have long since avoided speaking about my childhood altogether.

In reality, I was a citizen of nowhere. Eleven homes in seven countries. Seven schools on three continents. Five different languages. Repeated, ongoing cultural change. Always the outsider, always the foreigner, always the “other.” No childhood friends. All childhood memories left in faraway places. No roots, no ties, no reference points. No extended family. No long-term friends.

As my mother lost her mind, she talked more incessantly about her work. Tales of the most depraved, degenerate parts of human nature became a routine backdrop to family life. The subject became so normal that my youngest sister, only four when my parents went to Rwanda, started playing make-believe games of genocide and child soldiers and orphaned victims of war. Dallaire once remarked that, upon returning to Canada, one of the things he found hardest to comprehend was that the world had simply carried on, oblivious to the genocide even having taken place. He couldn’t understand that people hadn’t risen up in protest at the evil unfolding before them. I have spent long stretches of my life wondering what it might be like to be normal and to not know all the things that my siblings and I came to know, to have parents who take you to a football match or the pub, instead.

The reprehensible “white saviour” slur is a means of accusing the white man of dehumanising his dark-skinned charge. Would that it were so. I would very much have liked it if my mother had failed to so humanise those children in Rwanda. I would have very much liked it if she could have walked away, unaffected and sane, and not turned a genocide in a far-flung land into a defining trauma in our family’s life; a permanent, disabling fracture in its consciousness.

The problem wasn’t an inability to humanise those children. It was the opposite. Dallaire, too, spoke of a particular fixation on one Rwandan boy the same age as his son, as well as the unbearable guilt he felt because he still had a family when so many had lost theirs. The problem was not dehumanisation but over-attachment and a failure to notice what my mother’s dissolution was doing to her own children. Even now, it is a picture of child soldiers she worked with that she has on her bedroom dresser, not one of her children or grandchildren. And yes, I know we are more fortunate than those children. Unimaginably more fortunate.