recent

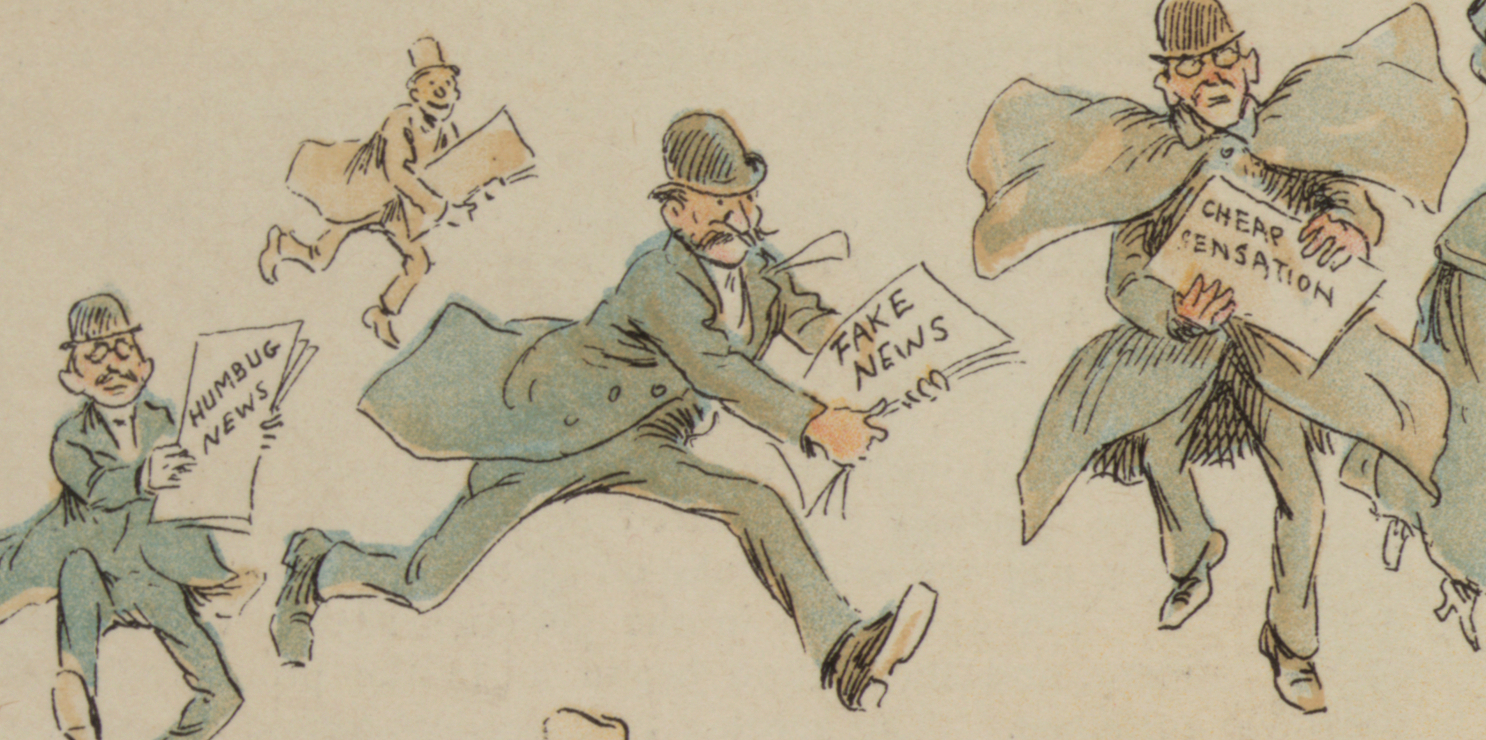

News, Pre-News, Fake News, and Statistics

For those of us engaged in showing young people how the media are supposed to work, there is no escaping the sturm und drang over fake news.

I’ve taken three lengthy Uber trips in the past month. Eventually, each of my drivers got around to asking what I did for a living. When I replied, ‟I teach journalism,ˮ two of the three reflexively exclaimed, ‟Ahh, fake news!ˮ It took the third a few extra lines of conversation, but she got there too in the end.

For those of us engaged in showing young people how the media are supposed to work, there is no escaping the sturm und drang over fake news. Needless to say, the term has itself acquired a patina of inauthenticity, given its most celebrated user’s tendency to invoke it to mean, ‟This news makes me look bad…so it’s fake.ˮ

In fairness, however, those of us who deal in the rules and rudiments of journalism understand that the fake-news meme cannot be dismissed simply as red meat that a pathologically insecure president tosses into his supporters’ den with discomfiting regularity. Actually, it’s an endemic issue in journalism, especially broadcast. The nature and baked-in presentation of news is such that its utility as a tool for understanding the world, let alone interpreting it, is almost nil.

Consider the familiar news-radio slogan, ‟You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world.ˮ

THIS IS A BALD-FACED LIE.

Newsworthiness, in its most elemental conception, is built on a foundation of anomaly, singularity, nonconformity: the clichéd ‟man bites dogˮ paradigm. Or here’s a second newsroom aphorism: ‟No one writes stories about the planes that landˮ (a line of particular resonance the past few weeks, for obvious reasons). It follows that, by definition, what the news business really gives you—with its unending parade of ugliness—is unreality. What you see each night on TV or hear from those all-news radio stations is not, in fact, your world. It is a negative image of your world, in both the photographic and tonal senses.

Put more directly, the news media provide you with a high-resolution snapshot of what life is not—a panoply of stories that, despite their disparate topics, resolve to a common theme: They are case after case in which, metaphorically speaking, men have bitten dogs.

In what follows, I give you your world, or at least your America…

Remember those planes? Our current Max 8 woes notwithstanding, they almost always land, at least in the United States. Each day, 23,911 out of 23,911 scheduled commercial flights take off and arrive safely. (The Economist pegs your odds of dying in a plane crash at one in 5.4 million. You are more likely to be hit by a meteorite.) Virtually no one who is unarmed, of any race, is killed by a cop or dies in a college hazing ritual, even when something goes awry. On any given day 50 million American children attend school without being shot. In much-maligned Chicago, the homicide rate is lower than that of various global destinations where we bankrupt ourselves to vacation. The employment rate hovers above 96 percent, and the average family living in federally defined poverty has a car, air conditioning, two TVs, and an Xbox; and in the category of ‟no, this is not a misprint,ˮ 43 percent of the poor own the homes in which they live. Plagues never emerge from forbidding third-world caves to blight the landscape. (Despite gloomy prognostications and any number of sensationalized “special reports,” HIV/AIDS never moved out of its core risk groups here in America. The Ebola ‟outbreakˮ of late 2014 was a non-starter.) The Republic slogs on despite the diverting shenanigans of the figureheads at the top. Even the current helmsman hasn’t undone us yet and probably won’t. Probably.

This is not some Panglossian delusion. It is daily life for almost everyone, almost every day. So yes, the events put before us on World News Tonight With David Muir did and do happen. It’s just that by every meaningful statistical yardstick, the vast majority of such events are margin notes to reality. This real news conjures an impression of life that is altogether fake. And yet this is where the canonical McLuhanism about media and message comes into play: If it’s on the news, we assume it’s newsworthy. Ipso facto.

Nor do journalists leave such inferences to chance. Today’s highly compensated news-delivery establishment does not want to be seen—or to see itself—as an institution that trades in trivia. Skilled at heightening immediacy and drama, news anchors (the so-called evening stars) and marquee correspondents thus make everything sound momentous and part of some ‟bigger storyˮ: as if all corporate executives are venal (but simply haven’t been caught yet), all schools warehouse legions of kids on the verge of erupting into the next Dylan Klebold (it’s just a matter of time), every new disease that slinks out of the rain-forest will inevitably kill us all (and if it doesn’t, the next Stephen Paddock will). Top journalists mainstream their marginalia, framing it as the zeitgeist. They also magnify the effect by connecting and contextualizing the dots, then surrounding the emerging diagram with piquant punditry bulwarked by other marginalia—pointedly selected, now, to bold-face the lines connecting those original dots.

The result is Narrative: the implied existence of significance where none necessarily exists. (Why necessarily? Well, some isolated events are destined to become part of bigger stories. But journalists have no inkling of this when they first begin flogging the original incidents.) Is the ‟campus rape crisisˮ more about women being exploited or men being deprived of due process? Is #TakeAKnee another tear in the social fabric, or is it symbolic of the inalienable rights around which the social fabric is draped? The answer depends on which journalist decides to contextualize which dots with what other dots.

All of which raises another question: Of all those marginal dots that vie for elevation to media melodrama, which do journalists choose to highlight each day? The answer to that question is governed by a process known as news judgment, wherein media gatekeepers apply their own criteria in deciding what’s vital for you, the great unwashed, to know. Though there’s often unanimity on lead stories, various outlets will have different slants on the composition of the rest of the day’s must-know news. So these events are not only anomalous, but cherry-picked from a large orchard of anomalous stories based on subjective criteria. What was important enough to get three minutes on MSNBC may very well go uncovered by Fox. And vice versa. So we don’t really see must-watch news. We see some news team’s assessment of what they think is must-watch news.

What, after all, is the inherent significance of a single cop’s shooting of a single unarmed black man? For that matter, in any given year, what is the significance of the shooting of several unarmed black men? Yes, it could be what epidemiologists call a cluster, indicating that ‟something is going on.ˮ Or it could be a mere aberration of the laws of chance, into which we inject extraneous meaning.

This much is certain: Rare is the week in which nightly newscasts fail to include some intimation of a police vendetta against Black America. Indeed, the victims’ names have been drilled into our national consciousness: Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Laquan McDonald. But our very familiarity with the names hints at a deeper truth: So infrequently does this occur that it’s possible to recite the names from memory. For this much is also certain: The math to support a pogrom against blacks simply isn’t there. According to a Washington Post database, police killed 19 unarmed black Americans in 2017. If you were one of the 29 million blacks age 18 and over, and unarmed, your odds of being killed by a cop were about one in 1.5 million. You were more likely to win $50,000 in the Powerball Lottery. Put another way, the 19 killings represented the death of .00000066 of all black citizens. Is something that befalls fewer than one ten-thousandth of 1 percent of citizens truly the crisis that feverish media coverage had us believing?

Nothing can be deduced from a sample that small. Across the spectrum of America, tragedies already acknowledged to be random and rare take a much higher toll than that. Each year, 75 of us die in lawnmower accidents, and on average, an American per day dies in his or her own bathtub. One does not expect to see CNN air one of its town hall specials on malevolent bathtubs—and if in a given year 40 of the 75 lawnmower victims happen to be black, we’d not likely investigate whether lawnmowers had developed racist tendencies. Even fatal lightning strikes, though trending downward, claim more lives than the shootings of young men that command the airwaves for weeks at a time.

Another gloomy trend in modern TV news’ continuing slide toward theater is what might be termed pre-news: extensive reporting on events that are ‟sort of happeningˮ but the resolution and ultimate import of which are far from certain. In their frenzy to out-Nielsen one another on stories with the potential to be Big News (or so says that infernal news judgment), the media indulge in days or weeks or months of reporting on events that would surely be epochal, save for one minor detail: They haven’t happened yet. Some of them never happen.

We see this in the case of Trump’s Russia woes. There may be collusion. Or there may not be. If there is collusion, Trump may be impeached. Or he may not be. This has gone on, virtually uninterrupted, since the day of his election. As Dave Barry has joked, ‟You can tune into CNN anytime, day or night, and you are virtually guaranteed to hear the word ‘Russians’ within 10 seconds, even if it’s during a Depends commercial.ˮ

Although this tendency toward hype has long existed in TV news, the media perfected the art form during the 1990 run-up to Desert Storm. With journalists coast to coast salivating over America’s first truly live war, we were treated to weeks of speculation about what would happen once that opening sortie was launched. A few sample prognostications:

- We’d lose tons of planes.

- The Arab coalition would crumble.

- Israel was doomed.

- The region would be contaminated with bio-weapons.

- And God help us if we ever got involved in a ground campaign, which—we were informed by well-credentialed ex-Pentagon types now on retainer as analysts—could claim thousands of U.S. lives. Thousands!

Networks repeatedly quoted Saddam’s vow to mount ‟the mother of all wars,ˮ as well as his ominous prognostication that American society ‟cannot accept 10,000 dead in one battle.” Hell, even the unflappable Ted Koppel seemed…flapped.

Then the fighting started. A few days later it ended, and Saddam unceremoniously withdrew from Kuwait.

Since then, pre-news is most notable in the breathless coverage of looming hurricanes. The TV tempest commences as the actual tempest still lolls hundreds of miles offshore, with no one certain just how much of a threat it poses to the mainland. Soon the hypothetical storm engulfs the nightly news on all networks; indeed, as residents in the storm’s projected path evacuate, the other side of the highway will be glutted with news trucks on their way in. Next, parka-clad correspondents begin vying for the most blustery spot on desolate beaches, each one hoping to look wetter and more windblown than the next guy once the storm hits. (‟Hey, I found it first—go get your own damn vortex!ˮ) Enhancing this cinema-not-quite-verite are the requisite interviews with harried shopkeepers, insurance-company execs, and emergency functionaries right on up to FEMA. Lest anyone still miss the sledgehammer foreshadowing, interspersed is archival footage of Hurricane Katrina. All this—let us not forget—before the storm has dampened anyone with so much as a droplet.

Big Journalism tends to justify its obsessive coverage of maybe-tropical storms in terms of its mandate to provide ‟public service.ˮ That is beyond disingenuous. People in the path of the storm know that it’s coming; local news keeps them in the loop and gets them as prepared as they’re ever gonna be. There is no journalistically honest reason why residents of Lincoln, Nebraska need to be subjected to this ersatz reportage for three or four solid days before the storm arrives (or fizzles out).

It would be easy to play all this for laughs if the implications for suggestible consumers weren’t as grave as they are. For one cannot remain unaffected by this ceaseless parade of chaos, corruption and carnage. Even the most discerning and/or cynical viewer is bound to internalize the morbidity, the nihilism. First, for all the reasons aforementioned, what ends up on the news is tantalizing and provocative, because ratings demand that ‟sexyˮ stories crowd out all others. (A third newsroom aphorism: ‟If it bleeds, it leads.ˮ) Just as a sharply angled, highly emotive ‟based on a true storyˮ movie will stay with you, coloring your perception of the actual events, the sheer emotionalism of the news burrows in beneath one’s defenses. Second, when we consume the media’s offerings we are dealing with at least some phenomena, the actual prevalence of which is unknown to us; lacking the at-hand background knowledge to recognize when we’re being presented with relative minutiae (‟dog-biting menˮ), we’re inclined to take what we see at face value. When Dateline tells the story of gastric-bypass surgery—a procedure survived by 199 out of 200 patients—in terms of one man who died, that one death, a .5 percent exception, becomes the nation’s lens on the surgery, likely also affecting (or infecting) the viewer’s outlook on other aspects of healthcare.

The extent of this news-versus-reality distortion is easily legible in Gallup polling on crime in America. In 2017, for example, just 12 percent of respondents rated crime in their own neighborhoods as “very serious” or “extremely serious.” Yet 59 percent deemed crime in America as a whole “very serious” or “extremely serious.”

The paradox should be evident: America is the sum of all neighborhoods. If national crime were as pervasive as the majority of respondents believed, wouldn’t it have to be occurring in a lot more than 12 percent of people’s “own neighborhoods”? Such an enigmatic skew can only be explained in terms of the global impressions people get from media. Viewers know firsthand that their neighborhoods are safe—the problem is everyone else’s neighborhood! Or so they deduce from what they see on the news.

Similarly, think of the belief among growing numbers of Americans that race relations are in precipitous decline, even ‟as bad as they’ve ever been.ˮ (Perhaps people have forgotten, or are too young to remember, the KKK? Bull Connor’s police dogs and fire hoses? The church bombings of the 1960s? The Black Liberation Army’s early-70s guerrilla war against American cops? Or perhaps today’s grim wall-to-wall imagery simply overwhelms one’s perspective.) Think of how many young black men are traumatized if not enraged by the indefatigable slideshow of police malfeasance. And what is the reality at the heart of this trauma or rage? A phenomenon that occurs far less often than homeowners killing themselves with their own lawnmowers.

Outside of a 9/11 or a Katrina, only hindsight can tell us when a given random event or snippet of news was destined to transcend randomness and move into the realm of enduring consequence. No one can know this as it is happening—not me, not you, not Jake or Anderson or Sean or Tucker or any of them. To pretend otherwise is, well, fakery.