Cinema

Don't Deny Girls the Evolutionary Wisdom of Fairy-Tales

Yet, this is the sort of hysteria used to justify yanking away the wonderful fun of watching Disney princess films. Remember fun?

The view from moral high ground is best enjoyed after the check (for whatever you’re moralizing against) clears.

Rather like animal-rights activists who own a string of steakhouses, Disney film stars Kristin Bell and Keira Knightley spoke out recently against the bad examples they feel Disney princesses convey to girls. (Bell voiced the role of Princess Anna in Disney’s 2013 animated film Frozen, and Knightley stars as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Disney’s new live action feature, The Nutcracker and the Four Realms.) Knightley even used her Nutcracker promo tour to reveal that she’s banned certain Disney films from her own home. The Little Mermaid is one prohibited flick, and Cinderella is another—because, Knightley explains, Cinderella “waits around for a rich guy to rescue her.”

Of course, Knightley and Bell aren’t alone in their disapproval. There’s been a war on “princess culture” for some time. Legions of pink-phobic parents all but go into mourning whenever their daughter begs for some glitter-flecked, rosy-hued item in a store—as if it might cast a spell on her, sending her down the path to Stepfordhood instead of STEM.

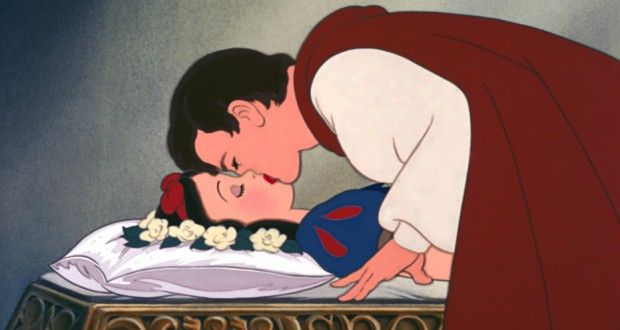

Snow White is kissed by her prince in the 1937 Disney production

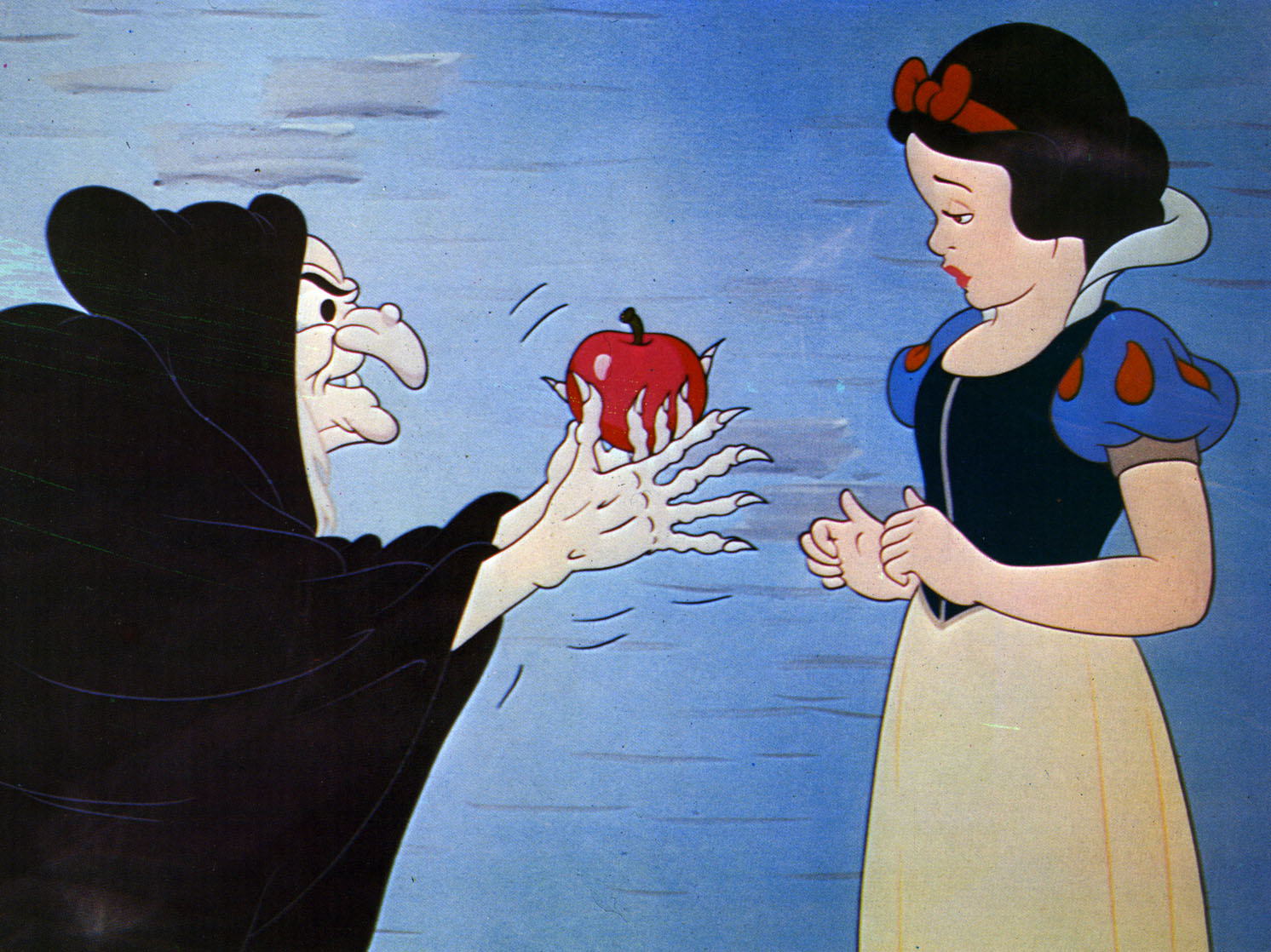

Bell even manages to find the #metoo in Snow White’s wakeup kiss from the Prince, lecturing her daughters that “you cannot kiss someone if they’re sleeping!” By this logic, one of the most beautiful forms of affection—a mother kissing her sleeping child—becomes a form of inappropriate contact.

This is crazythink. Children are not helped by adults projecting their fears in this way—stretching a prince chastely kissing a comatose princess back to consciousness into a thumbs up for having sex with a girl who’s passed-out drunk at a fraternity party.

Yet, this is the sort of hysteria used to justify yanking away the wonderful fun of watching Disney princess films. Remember fun? It’s a vestige from pre-1990 America—back before padded playgrounds, criminal background checks for parents working the school bake sale, and first-graders slaving over more nightly homework than I ever got in high school.

Ironically, far from contaminating young female minds, these Disney princess stories—and their fairy-tale-fic precursors—provide vitally helpful messages that parents could be discussing with their girls.

Cinderella, for example, revolves around the perniciousness of what researchers call “female intrasexual competition”—the often-underhanded ways women compete with each other. While men evolved to be openly competitive, jockeying for position verbally or physically, female competition tends to be covert—indirect and sneaky—and often involves sabotaging another woman into being less appealing to men. Accordingly, in Cinderella, when the king throws a ball to find the prince a wife, the nasty stepsisters aren’t at all “let the best woman win!” They assign Cinderella extra chores so she won’t have time to pull together something to wear. (Mean Girls, the cartoon version, anyone?)

Cinderella is assigned extra chores by her step-mother and step-sisters, thereby preventing her from getting ready to attend the ball

Psychologist Joyce Benenson, who researches sex differences, traces women’s evolved tendency to opt for indirectness—in both competition and communication—to a need to avoid physical altercation, either with men or other women. This strategy would have allowed ancestral women to protect their more fragile female reproductive machinery and to fulfill their roles as the primary caretaker for any children they might have.

Sure, today, a woman can protect herself against even the biggest, scariest intruder with a gun or a taser—but that’s not what our genes are telling us. We’re living in modern times with an antique psychological operating system—adapted for the mating and survival problems of ancestral humans. It’s often at a mismatch with our current environment.

Understanding this evolutionary mismatch helps women get why it’s sometimes hard for them to speak up for themselves—to be direct and assertive. And identifying this as a problem handed them by evolution can help them override their reluctance—assert themselves, despite what feels “natural.” Additionally, an evolutionary understanding of female competition can help women find other women’s cruelty to them less mystifying. This, in turn, allows them to take such abuse less personally than if they buy into the myth of female society as one big supportive sisterhood.

Such myths have roots in academia. Academic feminists typically contend that culture alone is responsible for behavior. If pressed, they’ll concede to some biological sex differences—but only below the neck. They deny that there could be psychological differences that evolved out of the physiological differences—and never mind all the evidence.

For example, evolutionary psychologists David Buss and David Schmitt explain—per surveys across cultures—that men and women evolved to have conflicting “sexual strategies.” In general, “a long-term mating strategy” (commitment-seeking) would be optimal for women and a “short-term mating strategy” (the “hit it and quit it” model) would be optimal for men. (Guess which model is championed in princess movies?)

In almost all species, it’s the female that gets pregnant and stuck with mouths to feed. So human women—like most females in other species—evolved to seek high-status male partners with an ability and willingness to invest.

This evolutionary imperative is supported by women’s emotions, which anthropologist John Marshall Townsend explains, “act as an alarm system that urges women to test and evaluate investment and remedy deficiencies even when they try to be indifferent to investment.” In Townsend’s research, even when women wanted nothing but a one-time hookup with a guy, they often were surprised to wake up with worries like “Does he care about me?” and “Is sex all he was after?”

In other words, the allure of “princess culture” was created by evolution, not Disney. Over countless generations, our female ancestors most likely to have children who survived to pass on their genes were those whose emotions pushed them to hold out for commitment from a high status man—the hunter-gatherer version of that rich, hunky prince. A prince is a man who could have any woman, but—very importantly—he’s bewitched by our girl, the modest but beautiful scullery maid. A man “bewitched” (or, in contemporary terms, “in love”) is a man less likely to stray—so the princess story is actually a commitment fantasy.

Aschenbrödel, by Carl Heinrich Hoff (1838–1890)

Because of this, princess films can be the perfect foundation for parents of teen girls to have conversations about the realities of evolved female emotions in the mating sphere. A young woman who’s been schooled (in simple terms) about evolutionary psychology is less likely to behave in ways that will leave her miserable—understanding that being “sexually liberated” might not make her emotionally liberated enough to have happy hookups with a string of Tinder randos.

As for the notion that watching classic princess films could be toxic to a girl’s ambition, let’s be real. Girls are being sent in droves to coding camp and are bombarded with slogans like “The future is female!” And young women—young women who grew up with princess films—now significantly outpace young men in college enrolment.

Children aren’t idiots. They know that talking mirrors and pumpkins that Uber a girl to the royal prom aren’t real, and they aren’t having their autonomy brainwashed away by feature-length cartoons—just as none of us dropped anvils on the neighbor kids after watching Road Runner. Ultimately, these bans of princess movies are really about what’s psychologically soothing for the parents, not what’s good for children. Preventing children from watching princess films and other fantasy kid fare gives parents the illusion of control, the illusion that they’re doing something meaningful and protective for their children.

Author and activist Lenore Skenazy urges parents to go “free range”—give their kids healthy independence, such as by letting them ride their bikes around the neighborhood without being accompanied by a rent-a-mercenary. I suggest parents also go psychologically free range. This means allowing children to watch classic Disney films instead of giving in to the ridiculous panic that their daughters will start seeing “princess” as a career option.

Stories give us insight into successful human behavior; they don’t turn us into fleshy robots who act exactly as the characters do. Understanding this is essential, because if we instead succumb to the current paranoia, we’ll have to remove much of the fiction from the high school curriculum— lest, say, Edgar Allan Poe’s Tell-Tale Heart lead yet another generation of young readers to murder their roommates, cut them up, and stash them under the floorboards.

Amy Alkon sneers at “self-help” books and instead writes “science help”—translating research from across scientific disciplines into highly practical advice. Her new science-based book is Unf*ckology: A Field Guide to Living with Guts and Confidence. Follow Amy Alkon on Twitter at @amyalkon.