Books

What Can We Learn from Dictators' Literature?

Dictators, of course, are terrible people. They also tend to be terrible writers. Yet many tyrants have entertained the illusion that they were literary super geniuses. Mein Kampf and Quotations from Chairman Mao (aka The Little Red Book) are the best-known works in the dictatorial canon, but they represent only a fraction of the awfulness on offer in a vast, infernal library. There are so many other books: from Lenin’s The Development of Capitalism in Russia to Khomeini’s Islamic Government to Gaddafi’s The Green Book and beyond.

In the heyday of 20th century tyranny, the writings of dictators were placed at the center of their personality cults, officially revered as sacred texts, and imposed upon (literally) captive audiences. That the books were frequently unreadable mattered little when the authors controlled the printing presses and the education systems, and could imprison or execute anyone who gave them a bad review.

And yet, when regimes fall, how quickly these books vanish. Those who suffered under the dictators wish to move on, while those who did not are put off by the devastated economies, piles of corpses, and generally atrocious prose. Understandable as this may be, I don’t think it’s such a good idea to let these books disappear from memory. Today, a generation has come of age that doesn’t remember the Cold War, and which knows little of the ideologies and simplifications that inspired so much carnage in the last century, but which increasingly holds positions of influence in media, academia, publishing and politics.

Alarmed by this, around eight years ago I set out to read the works of these tyrants, doing for dictator lit what Harold Bloom did for the Western canon in the 1990s. What did they write? Did they actually write the books themselves? What did they have in common? I wanted to know the answer to these questions and more.

* * *

Many people assume that, like Hollywood celebrities, dictators do not write the books that bear their names. But while this is often true (Leonid Brezhnev could barely be bothered to read a book, let alone write one) it is not a universal rule.

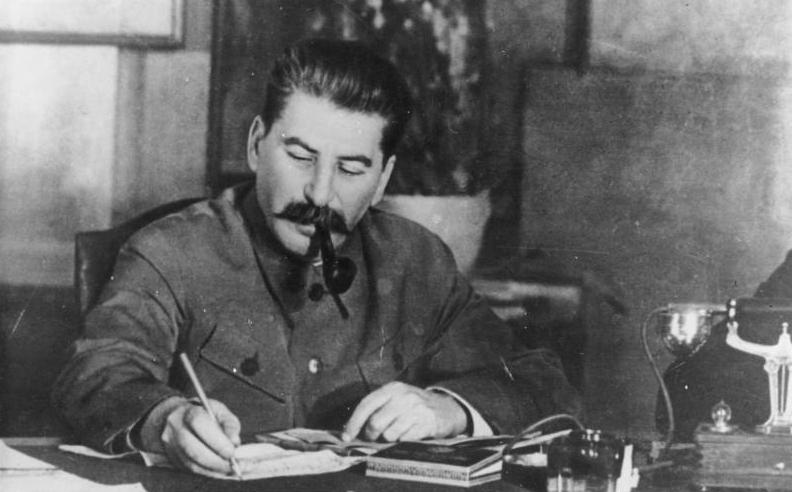

In fact, 20th century dictators were often writers before they were political leaders, rehearsing their ideological fantasies on paper in anticipation of the day when they would have entire populations at their mercy. At one end of the century, you have Lenin and Mussolini who both had two decades worth of published work behind them when they ascended to power; at the other, you have the Ayatollah Khomeini, writing thick volumes on Islamic jurisprudence and theology before he became the supreme leader of Iran. But dictators also write when they are in power: For instance, Lenin, Stalin, Franco, Saddam Hussein, Salazar, Gaddafi and Mao all found time to write, despite their busy schedules.

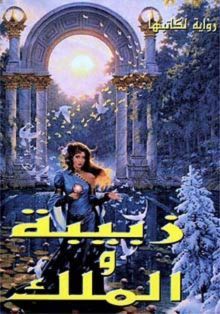

The variety is startling. There are novels: Mussolini wrote The Cardinal’s Mistress, a historical potboiler; Franco produced Raza, a fictionalized account of the Civil War, while Saddam Hussein wrote four novels in the last years of his regime, among them the historical romance Zabiba and the King. Gaddafi wrote prose miniatures; Mao, Salazar, Stalin and Ho Chi Minh dabbled in poetry; Stalin wrote a pamphlet on linguistics; Enver Hoxha, the dictator of Albania, wrote a sequence of memoirs vast enough to rival Proust, while Kim Jong-il issued treatises on opera, journalism and cinema containing piercing insights such as: “A film’s images must look good on the screen.”

Most of these books are rubbish; but they are rubbish in interesting ways. Read enough tyrant prose and you get a sense of the authors as individuals: the bilious yet brilliant Lenin, the steely, plodding Stalin, the bumptious Mussolini, the stupendously dull economist-dictator Salazar…and then there’s Saddam Hussein, writing about leadership, loneliness, rape and bestiality in Zabiba and the King:

Even an animal respects a man’s desire, if it wants to copulate with him. Doesn’t a female bear try to please a herdsman when she drags him into the mountains as it happens in the North of Iraq? She drags him into her den, so that he, obeying her desire, would copulate with her? Doesn’t she bring him nuts, gathering them from the trees or picking them from the bushes? Doesn’t she climb into the houses of farmers in order to steal some cheese, nuts and even raisins, so that she can feed the man and awake in him the desire to have her?

At the core of the canon is the immense accumulation of verbiage generated by communist dictators, who emerged from the “publish or perish” socialist tradition whereby revolutionary leaders established their authority by producing works of “theory.” Lenin came to power with a ready-made bibliography—the first edition of his collected works began publication in 1920, while the Russian Civil War still raged.

When Lenin died, Stalin quickly established himself as the preeminent interpreter of the mummy in the mausoleum. In the first Soviet satellite state of Mongolia, the dictator Choibalsan had Lenin and Stalin’s works translated, although many party members could not read. Across central and eastern Europe, Stalin’s satraps demonstrated their ideological bona fides by issuing volumes of speeches and essays littered with references to Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, much as critical theorists today cite the same handful of authorities with deadening predictability.

Dictators on the right, rejecting Marx’s historical metaphysics in favor of their own mythologies of blood and soil, preferred to present themselves as sui generis. Hitler concealed the influence of Mussolini in Mein Kampf, giving him only a tiny mention in part II; Mussolini dismissed Hitler’s book as “that enormous brick which I have never been able to read.” Yet communism was the specter haunting their texts. When the ex-socialist Mussolini sat down to write Fascism: Its Theory and Philosophy with the philosopher Giovanni Gentile, the anxiety of influence was evident as he pursued an aggressively anti-materialist direction. Fascism became a Holy Ghost-like entity that “permeates the will like the intelligence” and which “descends deeply and lodges in the heart of the man of action as well as the thinker, of the artist as well as the scientist.” It is, says Mussolini, “the soul of the soul.”

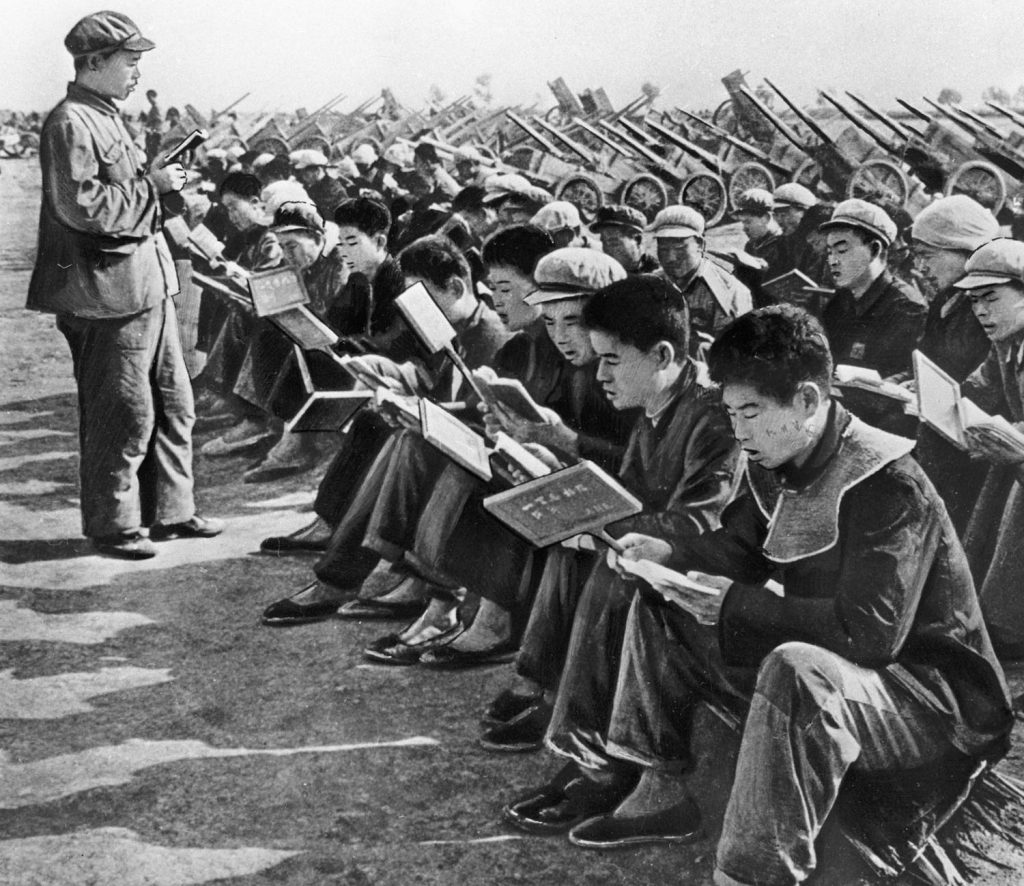

Dictator lit peaked in the mid to late 1960s with The Little Red Book. Over a billion copies were in circulation by the time Mao died, containing such staggering insights as this:

It [materialist dialectics] holds that external causes are the condition of change and internal causes are the basis of change, and that external causes become operative through internal causes. In a suitable temperature an egg changes into a chicken, but no temperature can change a stone into a chicken, because each has a different basis.

Yet at the height of the Cultural Revolution, this stupendously dull tome inspired violent schisms between fanatical bands of Maoists, as well as outbreaks of murder and even cannibalism in the countryside. Meanwhile, newspapers carried reports of miraculous healings: the “Word of Mao” could cause tumors to disappear and the blind to see. Eventually, the delirium passed, but not before Mao and his disciples had wrought unfathomable carnage upon the nation.

* * *

Each dictator-author is terrible in his own way, yet they also share traits in common. Narcissism? Check. Megalomania? Check, although such characteristics are also occupational hazards among writers who don’t have squads of secret police at their command. But wait, there’s more.

For instance, although dictator-authors of both Left and Right positioned themselves as champions of the masses, very few were horny-handed sons of toil. Frequently, they were well-read intellectuals excluded from prestige positions in their societies: minor nobles, provincial intellectuals, the sons of wealthy farmers, ex-monks, frustrated artists, autodidacts. Their professed rage at injustice concealed bitter resentment, and ideology served as a fig leaf masking a tumescent desire for power and vengeance.

Like obfuscators of all eras, dictator-authors deployed opaque jargon to mask their mendacity and confer upon banalities a spurious sense of depth. Being unreadable was not a flaw: It helped them position themselves as super geniuses, uniquely qualified to rule. Tedium was a literary strategy designed to force the reader into submission. In their revolutionary stages, they were often sincere; but in established regimes, their words became tools of humiliation. As Anthony Daniels observed of North Korea “…by endlessly asserting what is patently untrue, by making such untruth ubiquitous and unavoidable, and finally by insisting that everyone publicly acquiesce in it, the regime displays its power and reduces individuals to nullities.” Humor was impossible in this framework; laughter would undermine the entire project.

Yet dictators also used clear language, especially when denouncing enemies. Lenin, author of the impenetrable Materialism and Empirio-criticism (1909), was also adept at crafting slogans such as the enduring “Communism is Soviet Power plus electrification,” and the man who encouraged revolutionaries to pour acid on cops in Tasks of Revolutionary Army Contingents (1905). Stalin happily smeared Social Democrats as “Social Fascists.” Mao described his own propaganda department as the “Palace of the King of Hell.” These were slurs that stuck, and were deadly.

Striking, too, is their awe at the power of the written word. Many dictators had been transformed by books: Lenin modeled himself after a character in Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done? While Stalin went by the pseudonym “Koba,” the hero of the potboiler The Patricide. In his own What is To Be Done? Lenin argued that he could use a newspaper to express his will and effectively write the revolution into existence. Once the revolutions failed to deliver, dictators attempted to overwrite reality with propaganda. A side effect of this awe was a terror of the power of wrong words, resulting in language policing and strict policies of censorship.

Then there are the “terrible simplifications,” the division of the world into warring camps of good and evil, the categorization of huge swathes of people on the basis of immutable characteristics such as race or class, the casting of life as a struggle for power between the righteous and the wicked, the latter of whom must be re-educated, repressed, exiled or exterminated. Mein Kampf is explicit in its violence, but there are many other dictator texts which treat life as an apocalyptic struggle between “us” and “them,” thus providing implicit license for all kinds of monstrous cruelties.

* * *

Today, the tyrannical tradition has entered its decadent, postmodern phase. In North Korea, Kim Jong-un’s word factory generates copious amounts of mendacious prose, every bit as unreadable as that of his forebears yet even more hollow, while in post-Soviet Central Asia, nationalism, myth and promises of a golden future are thrown at the hole where communism used to go. Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, the current Arkadag (“protector”) of Turkmenistan, is a prolific producer of banalities, among them a book entitled Tea: Healing and Inspiration. In Russia, Vladimir Putin’s has co-authored several books about judo, one of which was distributed free to millions of Russian schoolchildren.

More serious, and perhaps more sinister, are the works of the current leaders of Turkey and China. In his youth, Recep Tayyip Erdogan wrote, directed and starred in a play with the all-too revealing title Maskomya (“Masons, Communists and Jews”). Xi Jinping, recently anointed as leader for life by the Chinese Communist Party, has several books to his name, including the two-volume set The Governance of China. Volume one includes a stirring speech entitled “Carry on the Enduring Spirit of Mao Zedong’s Thought.” Just as in the past, today’s aspiring despots can be found hiding in plain sight in their published works.

Fortunately, we do not have to read the words of our leaders in what is still the free world. However, what we do have, courtesy of technologies that have equipped everyone with an internet connection with the means to be a publisher, is a mass proliferation of voices of a kind once restricted to low circulation ideological tracts.

Fortunately, these micro-Lenins are much less talented than the successful revolutionaries of the last century. They do have one advantage, however: effortless ubiquity. In the past, radicals had to wait until they had seized power before they could inflict their thoughts upon millions of people, and even then, the words were trapped in heavy books that many never actually read. Today the intolerant, factionalist, ranting, censorious, humorless, dogmatic-apocalyptic screeds of our would-be political saviors are effectively impossible to avoid; they are on our phones, in our feeds, in the comments below the articles we read online—and increasingly in the articles themselves.

When I set out to read the dictator canon all those years ago, I expected to suffer. I didn’t expect to find that dictator literature would serve as a blueprint for so much of the discourse of our era.