Art

Are Internet Memes a New Form of Literature?

When historians study ancient societies they use pottery, cave art, paintings and engravings as their sources. Memes can play the same role as one of the sources of history.

Every age has its form of literature, could the Internet meme be ours?

In literature, new genres are born because of the ceaseless human quest to find new and improved modes of communication. From Donald Trump to Brexit, some of our most profound, witty and honest observations are communicated through internet memes. Used for humour, therapy, gratification and protests, memes serve the internet generation well for they are free, instantly obvious and loaded with cathartic qualities.

If we analyse memes as a genre, we will find that it has more in common with traditional forms of storytelling, like fable and parable, than it has with the novel. Novel is a reflection of Capitalism in literature. It is formal, measured, commodified and portable. There is a standard version of the text, and an author to claim credit and royalties. Memes, on the other hand, are a return to fable in many ways. Just like fable, memes are community-driven, anonymously produced and open to modification. There is no need for a specialized degree or slick linguist skills to produce memes, for they rely on thought rather than abstract language.

Origins of memes lie in newspaper cartoons and comic strips. A typical meme consists of text on an image, the former originates from text messages and the latter follows from photography, which in turn is a successor to painting. On a more primal level, however, they stem from our insuppressible urge to engage in gossip, spread rumour and be the first to break news.

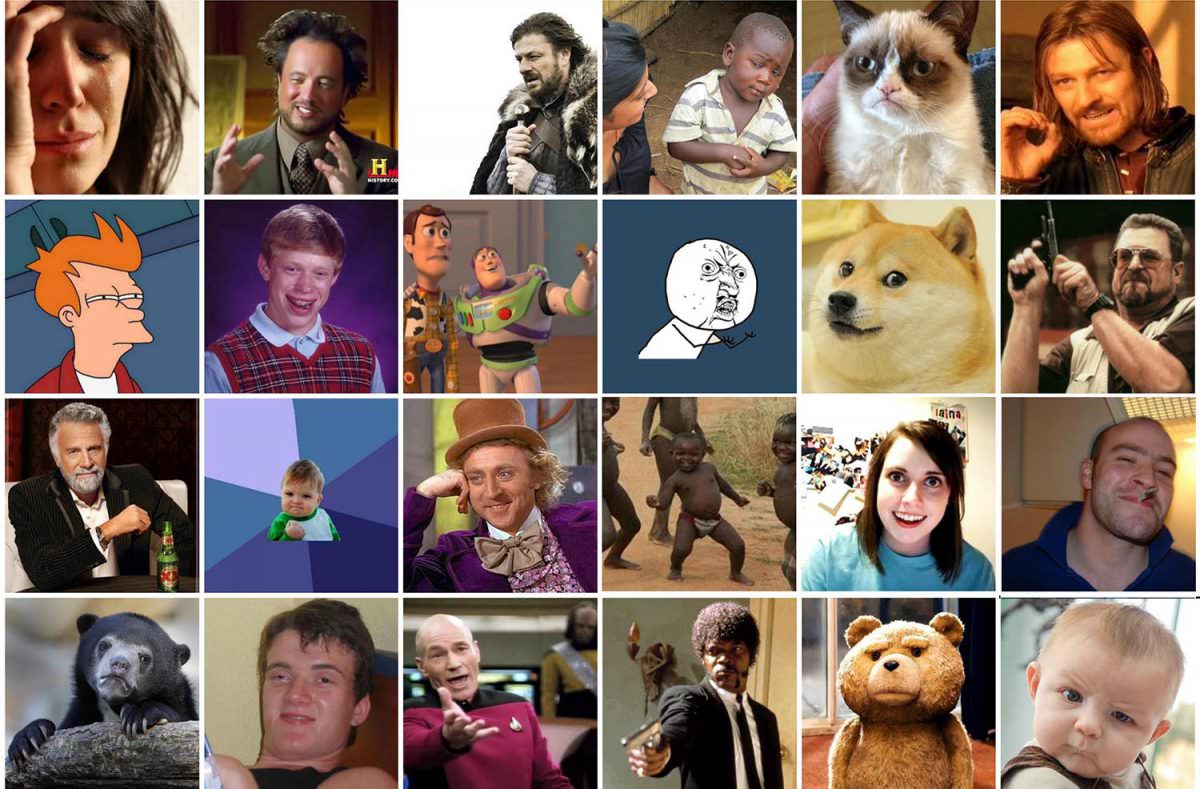

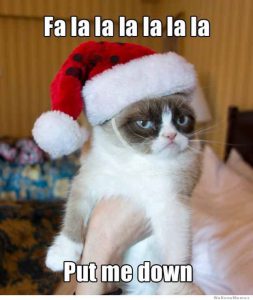

The central feature of memes is what art philosopher Walter Benjamin would have called a Quotable Expression. Just like a piece of text can be quoted and used in different settings, an expression used in memes is quoted by way of screengrab, painting, photography or digital artwork. Unlike films, poems and novels, memes are concentrated visuals depicting a limited number of scenes — mostly one. Now that internet has enabled ordinary people to connect for the first time in history, memes have brought forth the universality of quotable facial expressions. People who live in different cultures, speak different languages and have evolved in different climates are readily able to identify universal facial expressions like that of happiness, sadness, guilt, gratitude, annoyance, fear and disgust. In this hyper-connected world, memes allow transcultural expression. They even go one step further and project those emotions onto animals, like the famous Grumpy Cat, and anime objects.

The language of memes is not a short, internet version of writing. As linguist John McWhorter notes in his TED talk, in texting we write the way we speak. And we speak in word packets, and blurt out our thoughts because we’re in conversation with someone. Since the language of memes originates from text messages, it should be seen as a graphic form of speech rather than condensed, casual form of writing. This graphic speech is usually not complete or self-evident because it is only a part of the package, the other part being the image.

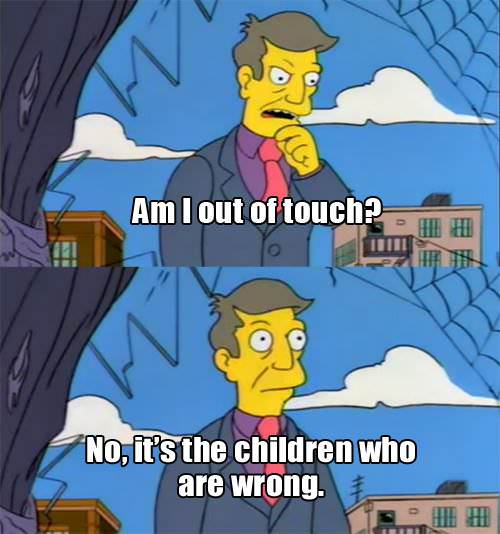

In memes, metaphor goes from the realm of language to the realm of image. Consider the meme about the quality of modern music. To say that modern music is trash is a cliché. To say it in film and print would mean using the word “trash”, but in meme a person can literally plug into a trash box and turn a redundant expression into a striking statement evoking laughter and realization of the state of music today. This critique of today’s music coming from consumers of music is much more impactful than lengthy op-eds in papers written by experts which, after all, reach a limited audience.

Memes are a reaction to the exalted Self depicted in the works of fiction. They are also a reaction against the exaggerations created by language, the impenetrability of art circles, the linguistic impediments to expression and limitations of other forms of literature that are failing to express the daily experiences of so many people. Published fiction withholds detail for fear of causing offense, or coming off as creepy, vulgar or cheap. This is primarily because published fiction has an author who will be held to account and readers will inevitably project all of the work back onto the personality of the author. The anonymity of the memes, however, creates an environment of encouraged transparency where we own our shortcomings and absurdities and laugh at them. We don’t project our experiences on fictional characters; we become the character as the meme announces “Me during abc…” or “Me when I was xyz…”

When historians study ancient societies they use pottery, cave art, paintings and engravings as their sources. Memes can play the same role as one of the sources of history. For anthropologists, memes can add to the data obtained by interviews, focus groups and surveys. But if memes are to be considered a form of literature, what would its criticism look like? Meme criticism would be a successor to criticism of painting, of endless commentaries on historical and modern paintings. All theories of literature, from New Criticism to Deconstruction, can be applied to memes. If theory can be extracted from nursery rhymes and folk songs, it can also be derived from internet memes. Classifying memes as a literary genre won’t change our consumption of it. We are not going to start buying albums or magazines of best memes of the month. What it would do, however, is provide new ground for the theory to expand upon and grapple with the challenge of representation, as it is comes not from an artistic class but from the people themselves.

Publishing is a business concern, a barrier defined by profit-and-loss calculation. For every novel published there are dozens that never see the light of the day. Same goes for short story, poetry and film proposals. Memes, on the other hand are not published but circulated. Just like fable, they start in a small corner and spread organically. This is their strength, but also their undoing, for publishing also preserves and organizes literature; something the meme form lacks so far. But in an age where the biggest encyclopaedia, Wikipedia, is driven by community, it is not hard to imagine the emergence of mechanisms to preserve and catalogue quality memes and filter out the junk.

Aneeq Ejaz is a student of literature currently enrolled in Masters in English Literature at Government College University, Lahore.