Cinema

Representation and the Communitarianization of Cinema

Identity has become the locus of cultural value and representation the means of its transmission.

A spate of recent cinema releases—Wonder Woman, Black Panther and, most recently, Crazy Rich Asians—have all been hailed in an almost repetitive, automatic way as ground-breaking. They are all fairly good films, but the reason for this excitement is not their artistry, or even their individual politics, but, at least with left-leaning critics, their portrayal of “powerful women,” “blackness,” and “Asian-ness,” respectively, within a mainstream Hollywood film. For the Left, the mere fact of representation—meaning the depiction of minority experiences and interests, or, more generally, seeing people who look like you—elevates these works to the position of cultural milestones.

In the view of the Left, to recognize a diversity of identities in art and culture is to enable self-empowerment and nurture a sense of collective solidarity. Black Panther, the recently anointed poster-child of representation, was even spoken about in spiritual terms when it was released. In an article entitled “I Dream a World: Black Panther and the Re-Making of Blackness,” Renée T. White wrote that “T’Challa [the hero] is a gateway to the past and a bridge to a different future. Here is a film that might just hold up a mirror, not one distorted by racism and white supremacy, but one that allows the viewer to say, ‘I am.’” 1

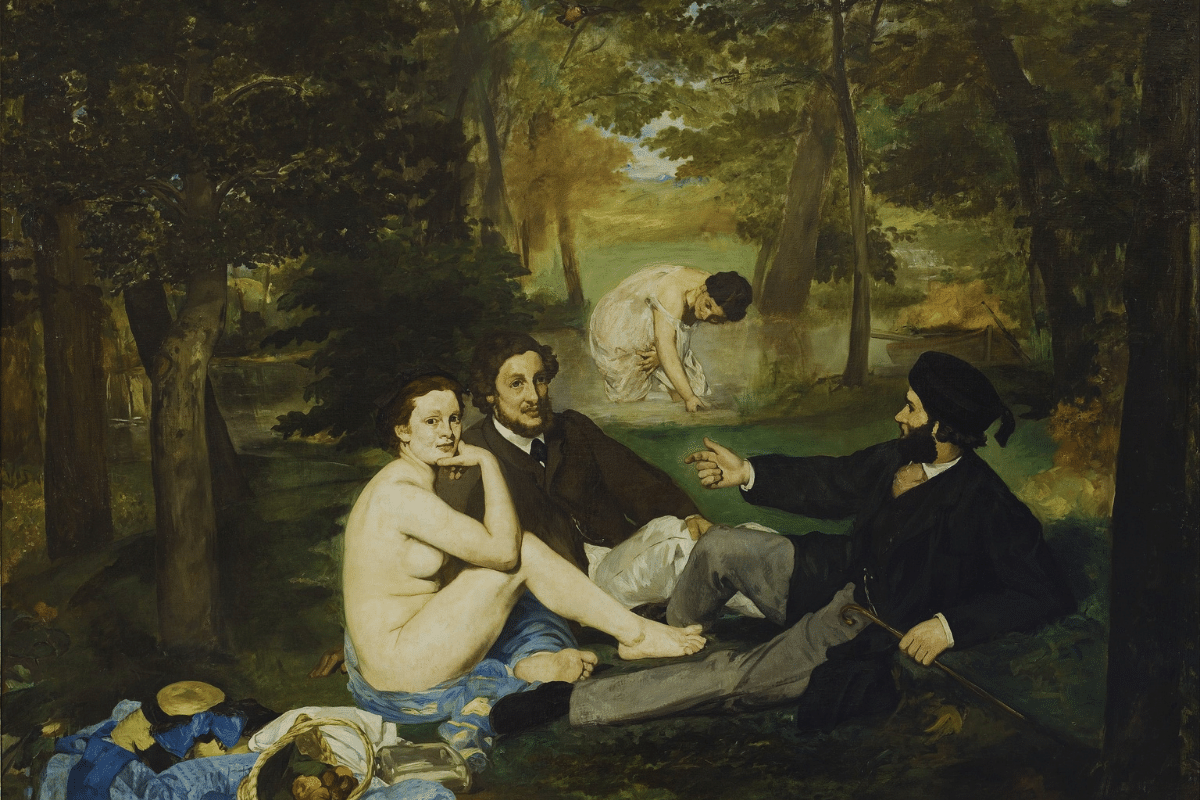

The film is not simply something autonomous to be contemplated, which might allow us to see the world differently. By making black identity occupy a space within culture supposedly reserved for white men only, it performs an important social and political function. This function has gone hand in hand with a rejection of cultural universalism—the idea that art is common ground upon which we can all meet in our shared humanity, regardless of gender, race, or class. This is crudely taken to mean “we are all the same” and that culture is simply the ideology of the majority—the distorting lens of white supremacy or patriarchy—imposed upon the rest. The only purpose of teaching culture, therefore, is to undermine it and expose the powers that secretly march behind it.

But universalism does not imply this at all. It acknowledges in its very premise that we are all shaped by our particular cultural or geographic backgrounds. But it goes a step further and says that as human beings we can use our imaginations to transcend difference as well as to understand it. But increasingly difference is seen not as something to transcend, but as the most important thing about a person. The universalist view says that we have important things we can say to each other because at the bottom of things we are all the same fundamental animal. The communitarian view says that what we say is only relative to our particular identities. In this scheme, representation becomes the highest ideal, because it is in the act of representing that culture can have any value for minority groups at all. Identity has become the locus of cultural value and representation the means of its transmission.

But what happens when our culture rejects universalism in favour of representation? Christopher Hitchens, speaking about the Salman Rushdie fatwa, outlined the danger of overturning culture to community interests: “There is an all-out confrontation between the ironic and the literal mind: between every kind of commissar and inquisitor and bureaucrat and those who know that, whatever the role of social and political forces, ideas and books have to be formulated and written by individuals.” Whether it is coming from religious extremists or diversity activists, the invasion of art by group interests turns it into something instrumental and an instrument of political control. It is also essentializes “the group” and makes it the lens through which art works must be formulated and understood. Culture, in this estimation, is nothing but another form of competition, with each group trying to secure a positive mirror for itself.

Representation as Cultural Democracy

Representation is not simply depiction or portrayal but “the action of speaking or acting on behalf of someone.” This implies that culture should be democratic and represent proportionally the interests and experiences of the identities that form society.

The argument goes that representation—as a representative sample of the population—will enrich art and culture because it will produce a diverse range of perspectives and truths about the world. This would be true if these perspectives could always be directly traceable to background, culture, race, gender or any other accidents of birth. But these things do not assume any values and, whatever template we are born with, we are continually being remoulded and refined by individual human experience and subjectivity.

If it were otherwise, a black person, for example, could claim to understand and represent their community (anyone who is black) simply by virtue of being black. A black person from Papua New Guinea and a black person from New Orleans could effectively represent each other on account of their skin colour alone. The idea that we are represented when we see people who look like us is plainly false, and it is patronising to assume that people are only able to identify with someone of their own race, or gender, or class. This kind of thinking is suggestive of a TV executive saying they want more LGBT or Muslim content, and trying to fill a tokenistic quota. But what exactly is Muslim content? It seems to mean nothing more than stories with characters who are Muslims. This corporate paint-by-numbers approach to culture assumes that simply having Muslims on the screen will necessarily represent them or speak to them on a deep level.

Of course, people of a particular background are more likely to share values and customs in common, but there is just as much diversity within groups as without. This is clear from the reception to Crazy Rich Asians. The story centres on Rachel Chu, a Chinese-American woman who follows her Chinese-Singaporean boyfriend Nick to his best friend’s wedding in Singapore and discovers that he and his family are, as the title suggests, incredibly rich. Although billed when it was released as a path-breaker for representation of Asians in Hollywood, it was not uniformly greeted with praise. According to some, it wasn’t representative enough, because it only showed a proportion of very wealthy Chinese-Singaporeans, and excluded the Malay, Indian and other minorities within Singapore who collectively account for a quarter of the population.

The story is not about minorities in America, but majorities in Singapore. Progressive representation is entirely dependent on where you are standing, making it impossible to please everyone at the same time. Perfect balance can never be achieved. Not every character can have lots of screen time, a full back-story and complex, nuanced dialogue. This is because every story is by necessity a microcosm of something. It is as much about choosing what to omit as well as include—where to focus and what to consign to the margins. Nobody thought, for example, that the protagonist of Get Out should have also been a closeted homosexual. It would have been a needless distraction from the film’s preoccupation with race and racism in contemporary America.

In the end, what draws people into a story is not the surface material, but the universal themes it explores. I don’t have to know anything about sailing to enjoy Captain Philips and I don’t have to be part of Chinese culture to connect with a masterpiece like In the Mood for Love. If art has no universal quality and is merely the mouthpiece of different groups, how can this connection be explained? Will a Chinese person necessarily have a deeper connection to In the Mood for Love than I do? Possibly. But, ultimately, I think that how much a film speaks to someone is not dependent their membership of a particular group. In the hands of a great artist, people don’t need to make great imaginative leaps to step inside a different time, or another person’s world.

Art retains value across cultures and across time, because talented artists have been adept at extracting the universal from the particular. Growing up in ancient Greece would have been strikingly different to growing up in modern-day Britain, yet the plays of that era are still performed today, and the themes they explore remain instantly recognisable. The diversity calculators tend to disparage universalism as a way to exclude rather than connect, and instead preoccupy themselves with superficial and irrelevant details such as “what percentage of the characters are gay?”

There are also degrees of Asian-ness to be factored into the equation. The casting of British-Malaysian Henry Golding, to play the boyfriend of Rachel, was initially criticised because he was mixed race and therefore supposedly not Asian enough to be the poster-boy for Asian representation. Golding revealed to Entertainment Weekly that the commotion over his casting felt “quite hurtful”:

People were like, “This guy’s half-Asian, he’s half-white, he’s not even full Asian,” and it comes to, like, how Asian do you have to be to be considered Asian? I’ve lived 16, 17 years of my life in Asia, and that’s most of my life. I was born in Asia, I’ve lived cultures that are synonymous with Asian culture, but it’s still not Asian enough for some people. Where are the boundaries?

The irony of identity politics is that it must employ the logic of racism in order to—supposedly—fight it. The Left would not hesitate to accuse a white nationalist of racism if he were to argue that brown-skinned Muslims could never be British despite being born and growing up there. Yet the comments made against Henry Golding, suggesting he could never be Asian enough despite being born and living in an Asian country for 17 years, make barely a ripple in the public consciousness. The white ethnonationalists and the left-wing identitarians may fight on different sides, but both make assumptions about people based on their ethnicity and enforce what they see as the authentic representation of their group.

Even before the film was released, it was transformed into a political project, with various activists staking their claims for what the film ought to be. It was going to be the Black Panther moment for the Asian community. I feel the same concern as writer Jiayang Fan in the New Yorker:

What does it mean that Crazy Rich Asians must accommodate simultaneous, conflicting demands—to tell a coherent narrative, to represent Asians of all stripes, to showcase Asian culture without alienating the dominant culture, to sell something palatable to the average American—when other movies, starring white leads, are asked only to tell a single story convincingly?

It means that Crazy Rich Asians has been turned into politics by other means. A new brand of representative art is under the thumb of a spurious collectivity, deciding what it should do to advance the interests of the group. It can never simply be what it is.

It is not that art can’t be political. It can have a political message. In fact, some of the great satirical works are political to their core. But this is different to a conception of art as a political tool, a second-class expedient to a political end. A work directed towards the advancement of a group’s cause and image is propaganda, not art.

We will end up with a situation where artists will have to presume to know what a particular community wants before they can even write the first words. Fictional characters will be seen as ambassadors for the interests of marginalized groups and cultures, their purpose, to advance the black perspective or the gay perspective in response to the dominance of the straight white male perspective. In effect, art will be used to serve a social cause rather than the truth.

If representation is a duty it is also a burden. White artists, without the burden of representation, have the freedom to focus less exclusively on the identity of content at the expense of aesthetics. This means that cultural universalism is not just for white people. Black directors like Steve McQueen can feel equally as comfortable making films about an Irish hunger strike, or a white New-York city executive.

The idea of art as a representative sample of the population—as something democratic—creates a false ideal. It says that a marker of good art is something that we can identify with, something that gives us a familiar picture of the world, a mirror. A flash of familiarity when we read a book or see a film can be a comforting thing. But art is also about completely upending the familiar, making us see things in a completely different way, and subverting our expectations. Most great art has been subversive in some way. It doesn’t pay attention to group demands and usually has a dissident relationship to the societies in which it is situated. I share the mindset that novelist Will Self inhabits: “I don’t write fiction for people to identify with and I don’t write a picture of the world they can recognise. I write to astonish people.”

Reference:

1 Renée T. White (2018), ‘I Dream a World: Black Panther and the Re-Making of Blackness’ New Political Science, 40:2, 427, DOI: 10.1080/07393148.2018.1449286