Art

The Artist and the Censor

An embrace of the art for art’s sake ideal is the greatest defense for artists against self-censorship. Those who defend art from moralizing or censure—who accept the reality of art’s autonomy—are those who see art for what it is.

Only proponents of the concept of art for art’s sake always can be depended on to oppose the censorship of art. The most robust argument against censorship lies not in appeals to Enlightenment values, which are subject to time, but in art itself. Those who believe art never requires external justification—which is to say, those who recognize art’s autonomy, whom I term “aesthetes”—understand best that art can never be weaponized effectively for or against a particular cause, and therefore never warrant censorship, because art has a life of its own.

Censors, and would-be censors, are part of the larger class of utilitarians who today are widely ensconced in the academy, the media, and arts and culture venues. You will know utilitarians by their mistaking of art for political activity, for community-building, for therapy. Art should produce results in the present, they contend—results for society and for the self. An ascendent belief among utilitarians, expressed by some and held more or less consciously by others, is that righteous art can stamp its righteousness on audiences, who will leave the museum or finish the poem with their priorities realigned, their commitments affirmed. For believers, herein lies art’s purpose: to sway hearts and minds. This fatuous idea undergirds activist art, which supposes its content can be conveyed directly into the psyche of the reader or audience, as though art were a delivery system in service to some more important thing, namely its “message.”

Those who would censor art extend this prevalent belief in art’s ability to stamp audiences with its righteousness to a belief that art can corrupt. In their estimation, certain artworks may be branded as dangerous, damaging, inciteful, offensive, unenlightened, hurtful, or triggering, all synonyms for “impure.” For censors, the effects on audiences of impure art are various but foreseeable: A work with the wrong message could turn audiences away from or even against their religion’s teachings, their responsibilities to themselves and others, or the pursuit of justice; neutral art could make them apathetic to the causes deemed imperative, so is in its own way threatening. Whatever direction they approach from—political, religious, or moral—censors suppose that the impact of an artwork on individuals can be predetermined.

Possibly you are an aesthete if you love art and find deranged this attitude that people are so porous, so claylike, that the propaganda of an artwork can seep into their hearts and imprint on their minds. Possibly you prefer to give beings who think and feel more credit.

* * *

“Then art is impotent, that’s what you’re saying,” obtuse utilitarians might well respond. Aesthetes argue no such thing; they argue art’s impact is both unpredictable and unquantifiable. Censors, and utilitarians more broadly, fundamentally misunderstand this about art. It eludes the blunt instruments of categories, charts, and data sets. Great art does not sleep. To say art is autonomous, that the importance of any work lies in itself and not in any external function it serves, is not to say art exists in a vacuum, beyond human concerns. Individuals who recognize that art has its own life are those capable of abandoning themselves—their “human concerns” included—to it. On the moment of entering the gallery, or sitting down before the film, or opening the book, they accept that the work will act on them with a force of its own.

Artistic intention, like audience expectation, is surmounted by art, which is why artists are often so forgivably crummy at talking about their own work. The fact that great art compels us to respond with all our attentiveness—sensual, emotional, psychological, intellectual, spiritual—is why, out of the academy, biographical and historicizing interpretations can close art down even as they open it up; why cultural studies analyses are typically so enervating and tangential; why paranoic critical theorists, who attend to humans only as socialized beings acted on by power structures, are terrible at responding to art’s own enlivening powers.

It’s because of art’s autonomy that art historian T. J. Clark could write The Sight of Death, a beautiful book, about the dozens of days he spent before two paintings by Poussin, and never get to the bottom of those paintings, never settle on a final feeling or idea about the paint applied to those canvases by a man 350 years dead. It’s because of art’s autonomy that art lovers can make pilgrimages to Florence and Rome to behold Michelangelo’s sculptures, and after years of looking at pictures in books be astonished by how the works in marble have seemingly nothing to do with their likenesses. The unpredictability of art’s effects on those who experience it is as true of Stein’s Tender Buttons and the Viennese Actionists’ mischief and Houellebecq’s novels as it is of the old masterpieces. And good art, itself protean, throws our own mutability back at us. Why else do we return to great books, keep the same art on our walls? Because we are always changing.

* * *

French artists of the mid-19th century had known the tyranny of censorship from the preceding decades of social unrest. Scholars have suggested that the art for art’s sake (l’art pour l’art) stance, which took off at that time, was a pragmatic move on the part of those artists in the aftermath of revolution. Their claim to artistic independence, operating beyond topical or social matters—the argument goes—was a front put up in order to evade censorship. This historical interpretation has two major flaws. First, it refuses to engage the substance of the “art for art’s sake” concept, which in no way demands that topical matters be ignored but distinguishes between the way art and the screed or tract engage such matters. And second, it disregards the great diversity of artists who subscribed to the l’art pour l’art ideal, ranging from the icy Parnassians to the irreverent Gautier and heretical Baudelaire, artists who do not seem to have been cowed by the political climate. Scholars, and critics like them, will tend to argue that art for art’s sake is nonviable because so many of them are desperate to see their own work as socially responsible.

Within the Communist state, the filmmakers of the Czech New Wave turned away from social realism but did not altogether avoid subjects and themes that could have had them censored. The result was a decade of extraordinarily imaginative works, in form and content. Within constraints, those courageous artists discovered what other parts of them are free.

Prominent examples of censorship over the last hundred years have generally included artworks censored at the stage when they first were, or should have been, available to audiences. The censors have been the authorities. Lady Chatterley’s Lover was banned in the United States and available to British readers only in expurgated form from 1932 until 1960, when upon publication of the full edition its publisher was prosecuted (unsuccessfully) by the UK government for obscenity. Turned down by American presses, Nabokov published Lolita first in France, though it was pulled from shelves only a year later and banned in Britain. Australia briefly overturned its ban on Pasolini’s Salò in the ’90s and permitted full distribution of the film only in 2010. Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary had already been bought by Charles Saatchi and exhibited internationally before Mayor Giuliani in 1999 sued the Brooklyn Museum of Art, where it was on display.

Whether it’s accurate to call a publisher dropping a book shortly before its release or some time after acquisition an instance of censorship is immaterial. Whether editors and agents, gallerists and curators, choose to work with certain artists is up to them; whom the Guggenheim and MacArthur foundations support is their business. If the old institutions are promoting dull and utilitarian art, plainly we are lacking for quality institutions and in need of new ones.

Today, in the realms of contemporary arts and letters, self-censorship is the new threat that must be confronted. Of course artists are self-censoring and conforming. The homogeneity of what is published, displayed, promoted, reviewed, taught, and awarded shows it. Those who would say there is not a self-censorship problem were of the opinion that the vapid story “Cat Person” was an important work of literature, and do not know any artists. Because of its dominance, the utilitarian attitude—which says the measure of an artwork is its “message” and on that basis it will be applauded, ignored, or denounced—is increasingly difficult for the ambitious young artist to shield herself from. In addition, the artist today must accept that in great swaths of the culture, she is taken to be more important than what she produces. Often, the art seems beside the point. Think whatever you like about Philip Guston’s paintings, but the emblematic event of our time is when four world-class museums postponed his retrospective because the artist’s political beliefs were not presented to viewers explicitly enough. Not the art but what the artist represents is being judged.

* * *

Our period of meekness must be replaced by one of bravery. Unserious, censorious people will tar artists and aesthetes as bigots and fascists. The incompetence of their diction is what most offends. To the charge that it is selfish or self-indulgent to promote the ideal of art for art’s sake, artists and aesthetes should respond: “It is the opposite of narcissistic to grant art its autonomy. Activist artists—paternalistic and utilitarian—are the narcissists, flattening the possibilities of art as they flatten those who engage it.”

Honest artists understand not only that their intentions will be thwarted by the creative process but that they cannot presume how an audience will be affected by the completed work. Those people incapable of experiencing art on its own terms will scold and glare at whatever does not conform to their dogmatic expectations. They would have our museum visits be like our dental checkups, full of works that promise to x-ray and treat our hard-to-reach parts. Art cannot be made for such people.

An embrace of the art for art’s sake ideal is the greatest defense for artists against self-censorship. Those who defend art from moralizing or censure—who accept the reality of art’s autonomy—are those who see art for what it is.

Alice Gribbin is an English writer living in Northern California. She’s currently writing a book on aesthetic sensibility.

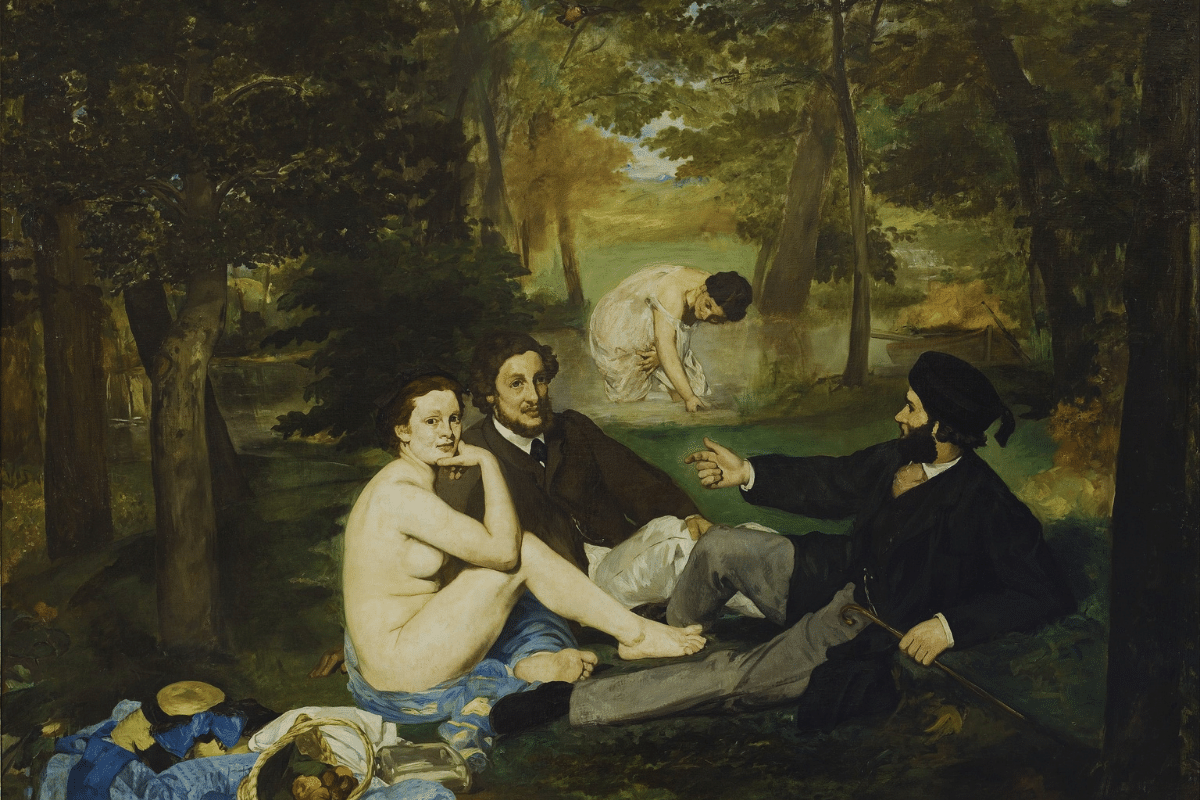

Image: Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe by Édouard Manet (wikicommons)